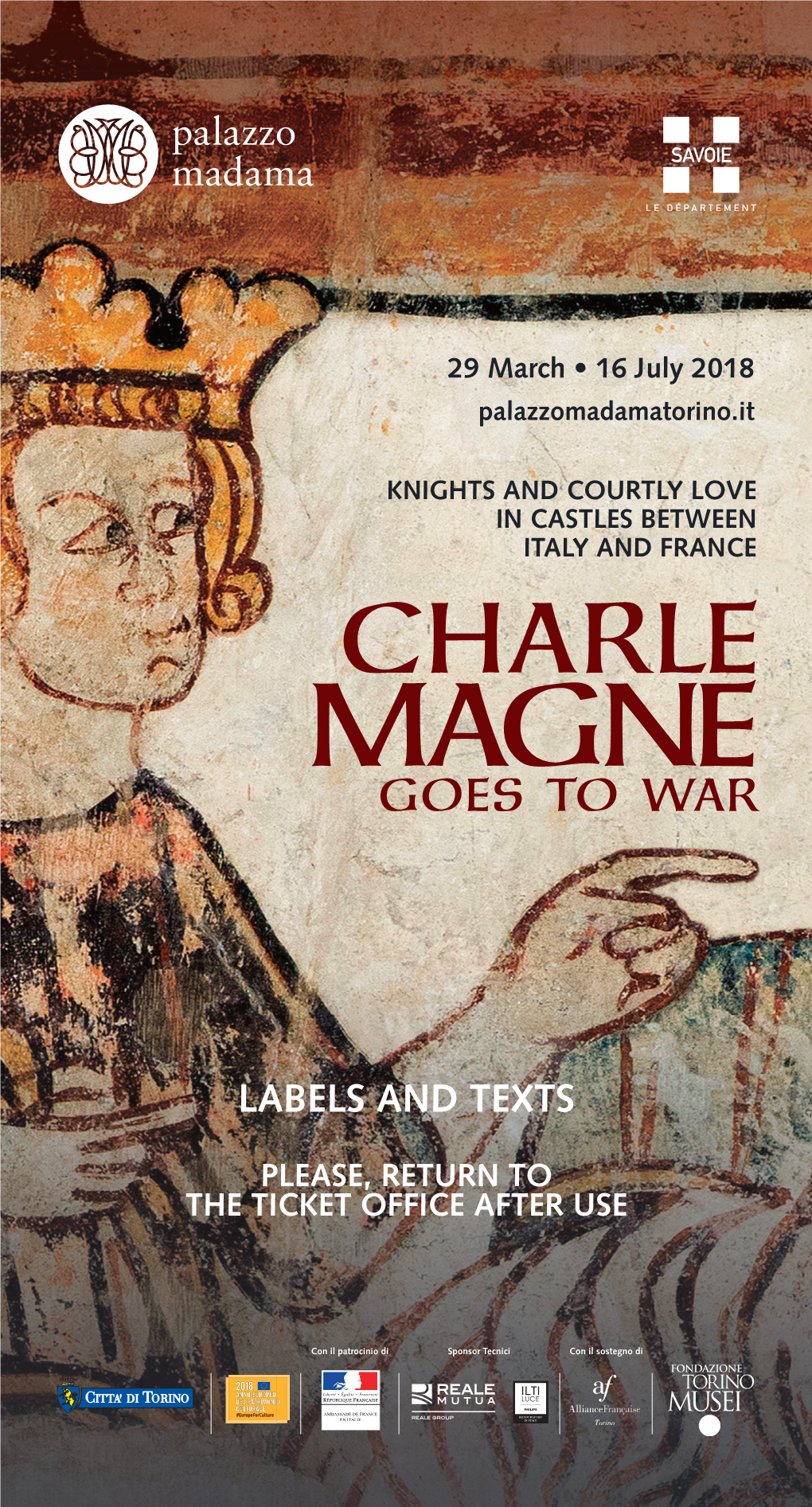

Charle Magne Goes to War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 94-Page Tour Booklet

Click city to Jump. Rome Lucerne Florence Paris The trip of a Lifetime London Venice EUROPE by TRAIN EUROPE by TRAIN place to the next, changing cities every night the way typical group tours do. We have selected six ROME of Europe’s most wonderful places and we stay for two or three nights in each of them to give you FLORENCE a good look around. VENICE About 25 years ago we did conduct several bus LUCERNE tours through Europe and were very dissatisfied with that approach. The tour moved through these PARIS places too quickly, and the bus was just not very LONDON comfortable, especially when you had to sit in it click to jump for an average of six hours every day. We looked at other Europe tours and found they were all the INTRODUCTION: same — stuck on the bus, changing cities every day, using hotels far from the center of town. This detailed book about our Rome to London The result was a very superficial tour that was train trip gives you an accurate idea of what the extremely tiring, and really did not show you very experience is all about. It describes the events of much. each day as they happen, so it is like a diary or a scrapbook of the tour. During the past 24 years we have conducted this trip 32 times, and have developed an ideal outline of events that take place each day, with a very efficient sequence of things that we see and do. Of course there are always minor variations in the daily routine described here, and there is some free time each day for you to pursue particular interests. -

Call for Data “Inventory and Condition of Stock of Materials at UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Sites”

Report No 83: Call for Data “Inventory and condition of stock of materials at UNESCO world cultural heritage sites”. Part II – Risk assessment September 2018 PREPARED BY THE SUB-CENTRE FOR STOCK OF MATERIALS AT RISK AND CULTURAL HERITAGE Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA), Rome, Italy CONVENTION ON LONG-RANGE TRANSBOUNDARY AIR POLLUTION INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATIVE PROGRAMME ON EFFECTS ON MATERIALS, INCLUDING HISTORIC AND CULTURAL MONUMENTS (ICP Materials) Report No 83 Call for Data “Inventory and condition of stock of materials at UNESCO world cultural heritage sites” Part II – Risk assessment Pasquale Spezzano1, Johan Tidblad2, Mirna Bojić3, Zrinka Radunić3, Vanja Kovačić3, Sonja Vidić4, Nina Zovko5, Stefan Brüggerhoff6, Markus Faller7, Ulrik Hans7, Terje Grøntoft8, Jessica Andersson2 1ENEA, Italy 2Swerea KIMAB AB, Sweden 3Ministry of Culture, Croatia 4Meteorological and Hydrological Service, Croatia 5Croatian Agency for Environment and Nature 6Deutsches Bergbau – Museum Bochum, Germany 7Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Testing and Research (EMPA), Switzerland 8Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU), Norway ENEA, Rome, Italy September 2018 http://www.enea.it/ Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Cultural objects ................................................................................................................................. -

Bibliografische Informationen

CENTRO STORICO 8 ANCIENT ROME 58 THE VATICAN 100 Piazza del Popolo 10 Romulus and Remus 60 The papacy 102 Ara Pacis Augustae 12 Campidoglio 62 The story of the Papal Piazza di Spagna 14 The Capitoline Museums 64 States 104 Villa Medici 16 Forum Romanum 66 St. Peter's Square 106 Shopping - High fashion From ancient temple Pope Julius II 108 and more 18 to Christian 68 Donato Bramante 110 Piazza Colonna 20 Julius Caesar 70 St. Peter's Basilica 112 The fountains of Rome 22 Foro di Augusto 72 St. Peter's Basilica: Fontana di Trevi 24 Foro di Traiano, The papal altar 114 Capital of the Republic 26 Colonna di Traiano 74 St. Peter's Basilica: Palazzo Barberini 28 Nero and the burning Vatican grotto 116 Santa Maria sopra Minerva 30 of Rome 76 Michelangelo 118 Piazza della Rotonda 32 Colosseum 78 The Sistine Chapel 120 Pantheon 34 Arco di Constantino 80 The Vatican Museums 122 The Roman gods 36 The Palatine Hill 82 Raphael 124 Palazzo Madama 38 Largo di Torre Argentina 84 The Vatican Apostolic Piazza Navona 40 Teatro di Marcello 86 Library 126 San Luigi dei Francesi 42 Forum Boarium, Swiss Guards 128 Campo de' Fiori 44 Santa Maria in Cosmedin 88 Castel Sant'Angelo 130 Evening strolls in Rome 46 Circo Massimo 90 San Paolo fuori le Mura 132 Piazza Farnese 48 Panem et Circenses - Santa Maria Maggiore 134 Getting around in Rome 50 Bread and games 92 San Giovanni in Laterano, The Ghetto 52 Caracalla Baths 94 Scala Santa 136 II Gesü 54 The Aurelian Walls 96 Monumento Nazionale a Via Appia Antica 98 Vittorio Emanuele II 56 Rome Bibliografische Informationen -

Redalyc.CRUSADING and MATRIMONY in the DYNASTIC

Byzantion Nea Hellás ISSN: 0716-2138 [email protected] Universidad de Chile Chile BARKER, JOHN W. CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY Byzantion Nea Hellás, núm. 36, 2017, pp. 157-183 Universidad de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=363855434009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BYZANTION NEA HELLÁS Nº 36 - 2017: 157 / 183 CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY JOHN W. BARKER UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON. U.S.A. Abstract: The uses of matrimony have always been standard practices for dynastic advancement through the ages. A perfect case study involves two important Italian families whose machinations had local implications and widespread international extensions. Their competitions are given particular point by the fact that one of the two families, the House of Savoy, was destined to become the dynasty around which the Modern State of Italy was created. This essay is, in part, a study in dynastic genealogies. But it is also a reminder of the wide impact of the crusading movements, beyond military operations and the creation of ephemeral Latin States in the Holy Land. Keywords: Matrimony, Crusading, Montferrat, Savoy, Levant. CRUZADA Y MATRIMONIO EN LAS POLÍTICAS DINÁSTICAS DE MONTFERRATO Y SABOYA Resumen: Los usos del matrimonio siempre han sido las prácticas estándar de ascenso dinástico a través de los tiempos. -

WALK ONE Campo Dei Fiori; Small Lanes; Chiesa Nuova; Piazza Navona

WALK ONE Campo dei Fiori; small lanes; Chiesa Nuova; Piazza Navona. CAMPO DEI FIORI Begin your first morning in the center of Rome at Campo dei Fiori, the best outdoor fruit and vegetable market. Then spend the rest of the day on a walking tour through some of the most fascinating and historic neighborhoods within the curve of the Tiber River. Campo dei Fiori is teeming with friendly people, tasty fruits, vibrant colors, animated conversations, varieties of vegetables, sweet smells, energetic vendors, local shoppers, and atmo- sphere galore. This setting is perfect, surrounded by very old buildings with cobbled pedestrian lanes leading off in all direc- tions into a great neighborhood we shall explore next. This friendly and lively piazza is one of the major focal points of the city, just three blocks south of Piazza Navona (coming up later in this walk) and an easy walk if your hotel is in the historic center. If you’re staying further away, take a taxi. Arriving any time in the morning is good, but earlier is better. Campo dei Fiori makes a great startfor our walk: it is the only main attraction opening by 6am and it is simply a wonderful morning scene. This magical Campo has multiple personali- ties, changing character throughout the day: Rome’s main veg- gie market in the morning, a ring of busy restaurants at lunch, peaceful in the afternoon, and a party scene at night. Campo dei Fiori’s produce stands are very popular with the nearby residents and chefs seeking fresh items on their daily shopping rounds. -

Chiesa Di San Luigi Dei Francesi in Campo Marzio

(092/37) Chiesa di San Luigi dei Francesi in Campo Marzio San Luigi dei Francesi is the 16th century titular and French national church located near Piazza Navona in rione VIII (Sant’Eustachio). The full dedication is to the Blessed Virgin Mary, St Dionysius (St Denis) and St Louis IX, King of France. History: The site was acquired by the French community in Rome from the monks of the Abbey of Farfam in 1478. The deal was facilitated by Cardinal Guillaume d'Estouteville. Pope Sixtus IV approved the project, sponsored by King Louis XI, and authorized the foundation of the Confraternita della Concezione della Beata Vergine Maria, San Dionigi et San Luigi Re di Francia, the ancestor of the present Les Pieux Etablissements. The area was full of remains of Roman buildings, including the Baths of Alexander Severus and the Baths of Nero. Pope Sixtus IV (1471-1484) confirmed the exchange uniting various small churches into a single parish in honor of “The Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, St. Dionigi (Denis) and St. Louis, King of France” (patron saints of the French nation), and also set up a Confraternity with the same name to manage the area. In the early 16th century, the Medici family took over. Cardinal Giulio de Medici, later Pope Clement VII, commissioned Jean de Chenevière to build a small round church for the French community here in 1518. Building was halted when Rome was sacked in 1527. In the mid-16th century, with the support from Caterina de’Medici who lived in the nearby Palazzo Madama, a new church was begun. -

PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 E-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8

The Crisis of the 14th Century Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 13 The Crisis of the 14th Century Teleconnections between Environmental and Societal Change? Edited by Martin Bauch and Gerrit Jasper Schenk Gefördert von der VolkswagenStiftung aus den Mitteln der Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly (1309–1321)“ / Printing costs of this volume were covered from the Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly 1309-1321“, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation. Die frei zugängliche digitale Publikation wurde vom Open-Access-Publikationsfonds für Monografien der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft gefördert. / Free access to the digital publication of this volume was made possible by the Open Access Publishing Fund for monographs of the Leibniz Association. Der Peer Review wird in Zusammenarbeit mit themenspezifisch ausgewählten externen Gutachterin- nen und Gutachtern sowie den Beiratsmitgliedern des Mediävistenverbands e. V. im Double-Blind-Ver- fahren durchgeführt. / The peer review is carried out in collaboration with external reviewers who have been chosen on the basis of their specialization as well as members of the advisory board of the Mediävistenverband e.V. in a double-blind review process. ISBN 978-3-11-065763-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947596 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

KAUFMAN-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Cheryl Lynn Kaufman 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Cheryl Lynn Kaufman Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Augustinian Canons of St. Ursus: Reform, Identity, and the Practice of Place in Medieval Aosta Committee: Martha G. Newman, Co-Supervisor Alison K. Frazier, Co-Supervisor Neil D. Kamil Joan A. Holladay Glenn A. Peers The Augustinian Canons of St. Ursus: Reform, Identity, and the Practice of Place in Medieval Aosta by Cheryl Lynn Kaufman, B.A.; M. A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedicated to Eric A. Kaufman with love Acknowledgements I have accumulated several debts of gratitude over my graduate school career. I am thankful to the Soprinendenza ai Beni Culturali e Ambientali della Regione Autonoma Valle d‘Aosta for permission to photograph the sculpture in the cloister of St. Ursus. For access to manuscripts in Aosta, I thank Don Franco Lovignana and the librarians at the Biblioteca del Seminario Maggiore and Archivio Storico Regionale. I am especially grateful to Dr. Paolo Papone for his gracious hospitality, the interesting conversations (in person and in email) regarding the cloister sculpture, and his kindness in sharing his dissertation with me before its publication. My visits to Italy and Switzerland have been enhanced by the hospitality of Greg and Lisby Laughery who provided a warm bed, lovely meals, and challenging conversations on my journeys to Switzerland. -

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE of MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, and the USE of CULTURAL HERITAGE in SHAPING the RENAISSANCE by NICHOLAS J

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE OF MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, AND THE USE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SHAPING THE RENAISSANCE By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP A thesis submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. and approved by _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Florentine House of Medici (1389-1743): Politics, Patronage, and the Use of Cultural Heritage in Shaping the Renaissance By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP Thesis Director: Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. A great many individuals and families of historical prominence contributed to the development of the Italian and larger European Renaissance through acts of patronage. Among them was the Florentine House of Medici. The Medici were an Italian noble house that served first as the de facto rulers of Florence, and then as Grand Dukes of Tuscany, from the mid-15th century to the mid-18th century. This thesis evaluates the contributions of eight consequential members of the Florentine Medici family, Cosimo di Giovanni, Lorenzo di Giovanni, Giovanni di Lorenzo, Cosimo I, Cosimo II, Cosimo III, Gian Gastone, and Anna Maria Luisa, and their acts of artistic, literary, scientific, and architectural patronage that contributed to the cultural heritage of Florence, Italy. This thesis also explores relevant social, political, economic, and geopolitical conditions over the course of the Medici dynasty, and incorporates primary research derived from a conversation and an interview with specialists in Florence in order to present a more contextual analysis. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

A Chinese-Drawn World Map Depicts Europe Between 1157 and 1166, and Reveals Sino-Europe Maritime Routes Already Existing in the Millennia Before Christ

1 A Chinese-drawn world map depicts Europe between 1157 and 1166, and reveals Sino-Europe maritime routes already existing in the millennia before Christ By Sheng-Wei Wang* 28 May 2021 Abstract This paper reports that a Chinese-based world map ‒ the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu《坤舆 万国全图》or Complete Geographical Map of All the Kingdoms of the World published by Matteo Ricci in 1602 in China ‒ depicts Europe in the period between 1157 and 1166, during the Southern Song Dynasty (南宋; 1127-1279), and that a network of trade routes ‒ the Maritime Silk Road routes connecting China and Europe ‒ existed already before Christ. The findings are based on: 1) a comparison of key geographical features in the European portion of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu with major European and Arabic maps from antiquity to the late sixteenth century; 2) a comprehensive examination of the geographical and historical information of each named European kingdom, principality, duchy, republic, state, confederation, province, county, region, autonomous or semi- autonomous region, city/town, peninsula, island, ocean, sea, lake and river depicted on the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu; 3) a historical record of China-Byzantine interactions during the rule of the Emperor Shenzong (神宗; 1048-1085) of the Northern Song Dynasty (北 宋; 960-1127); 4) archaeological findings from the “Nanhai One (南海一号)” shipwreck dated around the 1160s of the Southern Song Dynasty and discovered in the South China Sea in 1987; and 5) the latest archaeological surveys made by T. C. Bell in Ireland and the United Kingdom, revealing that the Chinese had actually operated in Western Europe as early as 2850 B. -

Background to Italy in the Time of Rosmini (1797 – 1855) C

A Background to Italy in the time of Rosmini (1797 – 1855) c. 1790 - 1855 Introduction Rosmini lived through an extremely turbulent period of European history. Through all of his early years, until he was eighteen (Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo a few days short of his eighteenth birthday), the continent was riven by wars which had their origins in the bloody, traumatic and epoch making events surrounding the French revolution and its consequences. Governments fell with bewildering regularity, more often than not bloodily, whilst constitutions, both republican and monarchical, were swept away and then often reverted. In this respect hardly a political unit in western and central Europe – city state, prince state, bishop state, empire, kingdom or republic – was unaffected. The sole exception was Great Britain, and even here Ireland was made part of the Union in 1800 and the novelty of income tax was introduced. Warfare was the norm, and although it bore little relationship to the ‘total wars’ of the twentieth century, it affected all classes and all areas to a greater or lesser extent. These events shattered pre-existing ideas – in a more brutal and physical form than the intellectual impact of the Enlightenment of the second half of the eighteenth century. The cost and impact of war speeded up the industrialisation of the continent, though the biggest contributor to this, the arrival of the railways, did not have a significant impact in Italy until after Rosmini had died. Italy It is essential to appreciate that Rosmini’s Italy was very different from todays. The Austrian Foreign Minister and later Chancellor in the post-Napoleonic era, Metternich, is reported to have said in 1847 that, Italy was a geographic expression.