Balloon Boy” Hoax, a Call to Regulate the Long-Ignored Issue of Parental Exploitation of Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

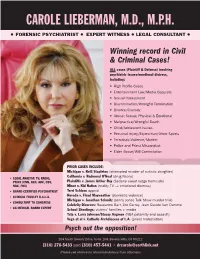

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. l FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST l EXPERT WITNESS l LEGAL CONSULTANT l Winning record in Civil & Criminal Cases! ALL cases (Plaintiff & Defense) involving psychiatric issues/emotional distress, including: • High Profile Cases • Entertainment Law/Media Copycats • Sexual Harassment • Discrimination/Wrongful Termination • Divorce/Custody • Abuse: Sexual, Physical & Emotional • Malpractice/Wrongful Death • Child/Adolescent issues • Personal Injury/Equestrian/Other Sports • Terrorism/Violence/Murder • Police and Priest Misconduct • Elder Abuse/Will Contestation PRIOR CASES INCLUDE: Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted murder of autistic daughter) California v. Redmond O’Neal • LEGAL ANALYST: TV, RADIO, (drug felony) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray PRINT (CNN, HLN, ABC, CBS, (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) NBC, FOX) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV → emotional distress) Terri Schiavo • BOARD CERTIFIED PSYCHIATRIST appeal Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather • CLINICAL FACULTY U.C.L.A. (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz • CONSULTANT TO CONGRESS (Jenny Jones Talk Show murder trial) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme • CA MEDICAL BOARD EXPERT School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Vega et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Psych out the opposition! 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108, Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 457-5441 [email protected] and • (Please see reverse for recommendations from attorneys) Here’s what your colleagues are saying about Carole Lieberman, M.D. Psychiatrist and Expert Witness: “I have had the opportunity to work with the “I have rarely had the good fortune to present best expert witnesses in the business, and I such well-considered testimony from such a would put Dr. -

Perceptions of Information Overload in the American Home

The Information Society, 28: 161–173, 2012 Copyright c Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0197-2243 print / 1087-6537 online DOI: 10.1080/01972243.2012.669450 Taming the Information Tide: Perceptions of Information Overload in the American Home Eszter Hargittai Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA W. Russell Neuman Department of Communication Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Olivia Curry School of Communication, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA In the last few decades Americans have integrated ca- This study reports on new media adopters’ perceptions of and ble television, the Internet, smart phones, blogging, and reactions to the shift from push broadcasting and headlines to online social networking into their lives, engaging a much the pull dynamics of online search. From a series of focus groups more diverse, interactive, always-on media environment. with adults from around the United States we find three dominant As was the case with most previous developments in media themes: (1) Most feel empowered and enthusiastic, not overloaded; technology, a few proponents have trumpeted the virtues (2) evolving forms of social networking represent a new manifes- of these devices (Negroponte 1995), but most academics tation of the two-step flow of communication; and (3) although and authors in the popular media are moved to warn of critical of partisan “yellers” in the media, individuals do not re- dire, dystopic consequences (Wartella & Reeves 1985). port cocooning with the like-minded or avoiding the voices of those There are concerns about sensory overload (Beaudoin with whom they disagree. We also find that skills in using digital 2008; Berghel 1997), media addiction (Byun et al. -

The Place of Creative Writing in Composition Studies

H E S S E / T H E P L A C E O F C R EA T I V E W R I T I NG Douglas Hesse The Place of Creative Writing in Composition Studies For different reasons, composition studies and creative writing have resisted one another. Despite a historically thin discourse about creative writing within College Composition and Communication, the relationship now merits attention. The two fields’ common interest should link them in a richer, more coherent view of writing for each other, for students, and for policymakers. As digital tools and media expand the nature and circula- tion of texts, composition studies should pay more attention to craft and to composing texts not created in response to rhetorical situations or for scholars. In recent springs I’ve attended two professional conferences that view writ- ing through lenses so different it’s hard to perceive a common object at their focal points. The sessions at the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) consist overwhelmingly of talks on craft and technique and readings by authors, with occasional panels on teaching or on matters of administration, genre, and the status of creative writing in the academy or publishing. The sessions at the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) reverse this ratio, foregrounding teaching, curricular, and administrative concerns, featur- ing historical, interpretive, and empirical research, every spectral band from qualitative to quantitative. CCCC sponsors relatively few presentations on craft or technique, in the sense of telling session goers “how to write.” Readings by authors as performers, in the AWP sense, are scant to absent. -

Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: a Call for an Interstate Compact

Child and Family Law Journal Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 6 5-2021 Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Family Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation (2021) "Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact," Child and Family Law Journal: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Child and Family Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Cover Page Footnote J.D., Barry University, Dwayne O. Andreas School of Law, May 2022. I would like to thank my husband for supporting me during the many sleepless nights which led to the completion of this note. Thank you to my boys for always calling to check in and visiting often. Also, I wish to thank my Senior Editor for helping me to clarify the intention of my note. Finally, thank you to Professor Sonya Garza for her extensive comments and direction—I am truly humbled by the time you dedicated to my success. This article is available in Child and Family Law Journal: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol9/iss1/6 Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Tabetha Bennett* I. -

Overwhelmed and Underinformed? How Americans Keep up with Current Events in the Age of Social Media

Institute for Policy Research Northwestern University Working Paper Series WP-11-02 Overwhelmed and Underinformed? How Americans Keep Up with Current Events in the Age of Social Media Eszter Hargittai Associate Professor of Communication Studies and Sociology Faculty Associate, Institute for Policy Research Northwestern University W. Russell Neuman John Derby Evans Professor of Media Technology University of Michigan Olivia Curry Undergraduate Research Assistant Northwestern University Version: December 2010 DRAFT Please do not quote or distribute without permission. 2040 Sheridan Rd. w Evanston, IL 60208-4100 w Tel: 847-491-3395 Fax: 847-491-9916 www.northwestern.edu/ipr, w [email protected] Abstract This working paper reports on a study of new media adopters’ perceptions of—and reactions to—the shift from push broadcasting and headlines to the pull dynamics of online search. From a series of focus groups with adults from around the United States, the researchers document three dominant themes: First, most feel empowered and enthusiastic, not overloaded. Second, evolving forms of social networking represent a new manifestation of the two-step flow of communication. Third, although critical of partisan “yellers” in the media, individuals do not report cocooning with the like- minded—nor avoiding the voices of those with whom they disagree. The three co-authors also find that skills in using digital media do matter when it comes to people’s attitudes and uses of the new opportunities afforded by them. Overwhelmed and Underinformed? :: 2 Taming the Information Tide Americans’ Thoughts on Information Overload, Polarization and Social Media In the last few decades Americans have integrated cable television, the Internet, smart phones, blogging and online social networking into their lives, engaging a much more diverse, interactive, always-on media environment. -

The Secret History of Extraterrestrials: Advanced Technology And

The Secret History of Extraterrestrials “With our present knowledge of the cosmos, there is now a real possibility of evolved and intelligent civilizations elsewhere in the vast cosmological space. And possible visitations and even encounters can no longer be ignored. Naturally we must tread with caution and not jump to conclusions too easily and too readily; but we must also keep an open mind and respect those bold investigators who apply rigorous research and common sense to this fascinating although very debated hypothesis. Len Kasten is such an investigator, and his book The Secret History of Extraterrestrials is a must for the libraries of all seekers of truth with unbiased minds.” ROBERT BAUVAL, AUTHOR OF THE ORION MYSTERY , MESSAGE OF THE SPHINX, AND BLACK GENESIS “Len Kasten has provided an up-to-date survey of the vast array of issues that are now emerging into the public consciousness regarding an extraterrestrial presence engaging the human race. For those who want to jump right into the pool and not just sit on the side and dangle their feet, take the plunge with The Secret History of Extraterrestrials.” STEPHEN BASSETT, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF PARADIGM RESEARCH GROUP “You can always count on Len Kasten to take you on a spellbinding galactic adventure, for he never fails to seek out ideas and theories that challenge your assumptions of what is true while firing your imagination. Whether in this dimension or another, be it past or future, your travels with Len Kasten will open your mind and introduce you to realities and experiences, you may have mistakenly assumed can exist only as fiction.” PAUL DAVIDS, DIRECTOR/PRODUCER OF JESUS IN INDIA AND EXECUTIVE PRODUCER/COWRITER OF ROSWELL: THE UFO COVERUP “This comprehensive book covers some of the most intriguing UFO and alien-contact cases ever reported. -

Case 2-7 Milton Manufacturing Company

Case 2-7 Milton Manufacturing Company Milton Manufacturing Company produces a variety of textiles for distribution to wholesale manufacturers of clothing products. The company‘s primary operations are located in Long Island City, New York, with branch factories and warehouses in several surrounding cities. Milton Manufacturing is a closely held company, and Irv Milton is the president. He started the business in 2005, and it grew in revenue from $500,000 to $5 million in 10 years. However, the revenues declined to $4.5 million in 2015. Net cash flows from all activities also were declining. The company was concerned because it planned to borrow $20 million from the credit markets in the fourth quarter of 2016. Irv Milton met with Ann Plotkin, the chief accounting officer (CAO), on January 15, 2016, to discuss a proposal by Plotkin to control cash outflows. He was not overly concerned about the recent decline in net cash flows from operating activities because these amounts were expected to increase in 2016 as a result of projected higher levels of revenue and cash collections. However, that was not Plotkin‘s view. Plotkin knew that if overall negative capital expenditures continued to increase at the rate of 40 percent per year, Milton Manufacturing probably would not be able to borrow the $20 million. Therefore, she suggested establishing a new policy to be instituted on a temporary basis. Each plant‘s capital expenditures for 2016 for investing activities would be limited to the level of those capital expenditures in 2013, the last year of an overall positive cash flow. -

Mothers on Mothers: Maternal Readings of Popular Television

From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. The volume examines the ways in which these women find pleasure, empowerment, escapist fantasy, displeasure and frustration in popular depictions of motherhood. The research seeks to present the MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION voice of the maternal audience and, as such, it takes as its starting REBECCA FEASEY point those maternal depictions and motherwork representations that are highlighted by this demographic, including figures such as Tess Daly and Katie Hopkins and programmes like TeenMom and Kirstie Allsopp’s oeuvre. Rebecca Feasey is Senior Lecturer in Film and Media Communications at Bath Spa University. She has published a range of work on the representation of gender in popular media culture, including book-length studies on masculinity and popular television and motherhood on the small screen. REBECCA FEASEY ISBN 978-0343-1826-6 www.peterlang.com PETER LANG From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. -

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:37:55 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit their Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 cable royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the cable royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

Looking At, Through, and with Youtube Paul A

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Communication College of Arts & Sciences 2014 Looking at, through, and with YouTube Paul A. Soukup Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/comm Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Soukup, Paul A. (2014). Looking at, through, and with YouTube. Communication Research Trends, 33(3), 3-34. CRT allows the authors to retain copyright. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking at, with, and through YouTube™ Paul A. Soukup, S.J. [email protected] 1. Looking at YouTube Begun in 2004, YouTube rapidly grew as a digi- history and a simple explanation of how the platform tal video site achieving 98.8 million viewers in the works.) YouTube was not the first attempt to manage United States watching 5.3 billion videos by early 2009 online video. One of the first, shareyourworld.com (Jarboe, 2009, p. xxii). Within a year of its founding, begin 1997, but failed, probably due to immature tech- Google purchased the platform. Succeeding far beyond nology (Woog, 2009, pp. 9–10). In 2000 Singingfish what and where other video sharing sites had attempt- appeared as a public site acquired by Thompson ed, YouTube soon held a dominant position as a Web Multimedia. Further acquired by AOL in 2003, it even- 2.0 anchor (Jarboe, 2009, pp. -

New Jersey Department of Children and Families Licensed Child Care Centers As of July 2014

New Jersey Department of Children and Families Licensed Child Care Centers as of July 2014 COUNTY CITY CENTER ADDR1 ADDR2 ZIP PHONE AGES CAPACITY Absecon Nursery Atlantic Absecon School Church St & Pitney Rd 08201 (609) 646-6940 2½ to 6 42 All God's Children Atlantic ABSECON Daycare/PreSchool 515 S MILL RD 08201 (609) 645-3363 0 to 13 75 Alphabet Alley Nursery Atlantic ABSECON School 208 N JERSEY AVE 08201 (609) 457-4316 2½ to 6 15 Atlantic ABSECON KidAcademy 101 MORTON AVE 08201 (609) 646-3435 0 to 13 120 682 WHITE HORSE Atlantic ABSECON Kidz Campus PIKE 08201 (609) 385-0145 0 to 13 72 Mrs. Barnes Play House 202-208 NEW JERSEY Atlantic ABSECON Day Care, LLC AVENUE 08201 (609) 377-8417 2½ to 13 30 Tomorrows Leaders Childcare/Learning 303 NEW JERSEY Atlantic ABSECON Center AVENUE 08201 (609) 748-3077 2½ to 13 30 Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Adventures In Learning 1812 MARMORA AVE 08401 (609) 348-3883 0 to 13 50 Atlantic Care After School Kids - Uptown Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Center 323 MADISON AVE 08401 (609) 345-1994 6 to 13 60 Atlantic City Day Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Nursery 101 N BOSTON AVE 08401 (609) 345-3569 0 to 6 87 Atlantic City High 1400 NORTH ALBANY Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY School Head Start AVENUE 08401 (609) 385-9471 0 to 6 30 AtlantiCare Dr. Martin L. Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY King Jr. Family Center 1700 MARMORA AVE 08401 (609) 344-3111 6 to 13 60 AtlantiCare New York Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Avenue Family Center 411 N NEW YORK AVE ROOM 224 08401 (609) 441-0102 6 to 13 60 Little Flyers Academy FAA WILLIAM J. -

“Octomom” As a Case Study in the Ethics of Fertility Treatments

l Rese ca arc ni h li & C f B Journal of o i o l Manninen, J Clinic Res Bioeth 2011, S:1 e a t h n r i c u DOI: 10.4172/2155-9627.S1-002 s o J Clinical Research Bioethics ISSN: 2155-9627 Review Article Open Access Parental, Medical, and Sociological Responsibilities: “Octomom” as a Case Study in the Ethics of Fertility Treatments Bertha Alvarez Manninen* Arizona State University at the West Campus, New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, Phoenix, P.O. Box 37100; Mail Code 2151, Phoenix, AZ 85069, USA Abstract The advent and development of various forms of fertility treatments has made the dream of parenthood concrete for many who cannot achieve it through traditional modes of conception. Yet, like many scientific advances, fertility treatments have been misused. Although still rare compared to the birth of singletons, the number of triplets, quadruplets, and other higher-order multiple births have quadrupled in the past thirty years in the United States, mostly due to the increasingly prevalent use of fertility treatments. In contrast, the number of multiple births has decreased in Europe in recent years, even though 54% of all assistant reproductive technology cycles take place in Europe, most likely because official guidelines have been implemented throughout several countries geared towards reducing the occurrence of higher-order multiple births.1 The gestation of multiple fetuses can result in dire consequences for them. They can be miscarried, stillborn, or die shortly after birth. When they do survive, they are often born prematurely and with a low birth weight, and may suffer from a lifetime of physical or developmental impairments.