Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: a Call for an Interstate Compact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

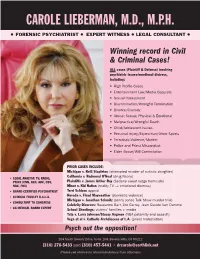

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. l FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST l EXPERT WITNESS l LEGAL CONSULTANT l Winning record in Civil & Criminal Cases! ALL cases (Plaintiff & Defense) involving psychiatric issues/emotional distress, including: • High Profile Cases • Entertainment Law/Media Copycats • Sexual Harassment • Discrimination/Wrongful Termination • Divorce/Custody • Abuse: Sexual, Physical & Emotional • Malpractice/Wrongful Death • Child/Adolescent issues • Personal Injury/Equestrian/Other Sports • Terrorism/Violence/Murder • Police and Priest Misconduct • Elder Abuse/Will Contestation PRIOR CASES INCLUDE: Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted murder of autistic daughter) California v. Redmond O’Neal • LEGAL ANALYST: TV, RADIO, (drug felony) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray PRINT (CNN, HLN, ABC, CBS, (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) NBC, FOX) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV → emotional distress) Terri Schiavo • BOARD CERTIFIED PSYCHIATRIST appeal Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather • CLINICAL FACULTY U.C.L.A. (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz • CONSULTANT TO CONGRESS (Jenny Jones Talk Show murder trial) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme • CA MEDICAL BOARD EXPERT School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Vega et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Psych out the opposition! 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108, Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 457-5441 [email protected] and • (Please see reverse for recommendations from attorneys) Here’s what your colleagues are saying about Carole Lieberman, M.D. Psychiatrist and Expert Witness: “I have had the opportunity to work with the “I have rarely had the good fortune to present best expert witnesses in the business, and I such well-considered testimony from such a would put Dr. -

Balloon Boy” Hoax, a Call to Regulate the Long-Ignored Issue of Parental Exploitation of Children

WHAT WILL IT TAKE?: IN THE WAKE OF THE OUTRAGEOUS “BALLOON BOY” HOAX, A CALL TO REGULATE THE LONG-IGNORED ISSUE OF PARENTAL EXPLOITATION OF CHILDREN RAMON RAMIREZ* I. INTRODUCTION On October 15, 2009, the world was captivated by the story of a little boy in peril as he allegedly floated through the Colorado sky in a homemade balloon.1 The boy’s parents, Richard and Mayumi Heene, first alerted authorities with an “emotional and desperate” 9-1-1 call, claiming that their son Falcon was in a balloon that had taken off from their backyard.2 Rescuers set out on a “frantic” ninety-minute chase that ended when the balloon “made a soft landing some 90 miles away;” but to their surprise, no one was in it.3 One of Falcon’s older brothers repeatedly said he saw Falcon get into the balloon before it took off, and a sheriff’s deputy said he saw something fall from the balloon while it was in the air, causing rescuers to fear the worst: Falcon fell out.4 The story appeared to have a happy ending after Falcon emerged from the family attic where he was hiding because his father yelled at him earlier in the day.5 That evening, the family appeared on Larry King Live on the Cable News Network (“CNN”) to tell their story, and when asked by his parents why he did not come out of the attic when they initially called for him, Falcon responded, “[y]ou guys said we did this for the show”; with that, suspicions began to arise.6 * J.D., University of Southern California Law School, 2011. -

New Jersey Department of Children and Families Licensed Child Care Centers As of July 2014

New Jersey Department of Children and Families Licensed Child Care Centers as of July 2014 COUNTY CITY CENTER ADDR1 ADDR2 ZIP PHONE AGES CAPACITY Absecon Nursery Atlantic Absecon School Church St & Pitney Rd 08201 (609) 646-6940 2½ to 6 42 All God's Children Atlantic ABSECON Daycare/PreSchool 515 S MILL RD 08201 (609) 645-3363 0 to 13 75 Alphabet Alley Nursery Atlantic ABSECON School 208 N JERSEY AVE 08201 (609) 457-4316 2½ to 6 15 Atlantic ABSECON KidAcademy 101 MORTON AVE 08201 (609) 646-3435 0 to 13 120 682 WHITE HORSE Atlantic ABSECON Kidz Campus PIKE 08201 (609) 385-0145 0 to 13 72 Mrs. Barnes Play House 202-208 NEW JERSEY Atlantic ABSECON Day Care, LLC AVENUE 08201 (609) 377-8417 2½ to 13 30 Tomorrows Leaders Childcare/Learning 303 NEW JERSEY Atlantic ABSECON Center AVENUE 08201 (609) 748-3077 2½ to 13 30 Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Adventures In Learning 1812 MARMORA AVE 08401 (609) 348-3883 0 to 13 50 Atlantic Care After School Kids - Uptown Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Center 323 MADISON AVE 08401 (609) 345-1994 6 to 13 60 Atlantic City Day Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Nursery 101 N BOSTON AVE 08401 (609) 345-3569 0 to 6 87 Atlantic City High 1400 NORTH ALBANY Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY School Head Start AVENUE 08401 (609) 385-9471 0 to 6 30 AtlantiCare Dr. Martin L. Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY King Jr. Family Center 1700 MARMORA AVE 08401 (609) 344-3111 6 to 13 60 AtlantiCare New York Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Avenue Family Center 411 N NEW YORK AVE ROOM 224 08401 (609) 441-0102 6 to 13 60 Little Flyers Academy FAA WILLIAM J. -

Will Rhode Island Be the Next Attorney State?

WWW.REBA.NET THE NEWSPAPER OF THE REAL ESTATE BAR ASSOCIATION MARCH 2020 • Vol. 17, No. 2 Supplement of Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly Boston Red Sox CEO Kennedy to deliver conference keynote Boston Red Sox CEO Sam Kennedy has overseen its growth from a start-up will deliver the keynote address at RE- to a world-class agency with an inter- BA’s Spring Conference luncheon May 4 national roster of clients that includes at the Four Points Sheraton in Norwood. the Red Sox, Liverpool Football Club, Kennedy’s remarks will include a NESN and Roush Fenway Racing, and Q&A session moderated by REBA partnerships with Boston College, Ma- board member Paul Alphen. jor League Baseball Advanced Media, Kennedy is entering his 18th season the Dell Technologies Championship, with the club and as well as a landmark marketing part- his third as presi- nership with NBA superstar LeBron dent and chief ex- James. ecutive officer. A native of Brookline who grew In addition to up within walking distance of Fenway his role with the Park, Kennedy, 45, joined the Red Sox ©Swampyank/Wikimedia Commons Red Sox, Kennedy in 2002 after working for the San Diego is chief executive Padres, from 1996 to 2001. of Fenway Sports Kennedy is active in the community KENNEDY Management, a and serves on the MLB International Will Rhode Island be sports marketing Committee and MLB Ticketing Com- and sales agency mittee, as well as the Beth Israel Dea- that is a sister company to the Red Sox coness Medical Center Trustee/Advi- the next attorney state? under the Fenway Sports Group family. -

Kid Nation Television Show Made to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Washington, D.C., Aug-Dec, 2007

Description of document: Informal complaints about Kid Nation television show made to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Washington, D.C., Aug-Dec, 2007 Released date: 30-January-2008 Posted date: 01-February-2008 Date/date range of document: 23-August-2007 – 12-December-2007 Source of document: Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, S.W., Room 1-A836 Washington, D.C. 20554 Phone: 202-418-0440 or 202-418-0212 Fax: 202-418-2826 or 202-418-0521 E-mail: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Enforcement Bureau, Investigations and Hearings Division 445 12th Street, S.W., Room 4-C330 Washington, D.C. 20554 JAN 30 2008 Via email Re: Freedom ofInformation Act Request FOIA Control No. 2007-134 This letter responds to your recent request, submitted under the Freedom ofInformation Act ("FOIA"). Therein, you seek, a copy of"complaints to the MMB and Enforcement Bureau pertaining to the Television show 'Kid Nation'." We have located 22 pages ofdocuments responsive to your request, copies ofwhich are enclosed. -

West Texas Your Life? Fr

‘Singing Priest’ Faith Value Most Americans of faith value religion returns in their life. How important is religion in West Texas your life? Fr. Arturo Pestin, left, who very somewhat was called back to his home 49% 40% diocese in the Philippines in CATHOLICS 2006 after serving in Midland, returned to the 65% 28% Diocese of San Angelo and PROTESTANTS was installed as parochial ANGELUSServing the Diocese of San Angelo, Texas administrator in Fort 72% 18% Volume XXVIII, No. 10 OCTOBER 2007 Stockton in September. MUSLIMS Dioce-Scenes/Pg. 20 Source: Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life: July 6, 2007 ©2007 CNS October 2007 S M T W T F S FESTIVAL SEASON ‘I am grateful 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 for Catholicism 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 over the years’ THIS MONTH By Jimmy Patterson daily email spiritual jour- in the Diocese Editor nal called “GodIssues” West Texas Angelus and distributes it to over 13 -- Fall Festival, St. Mary 10,000 recipients. Denison Queen of Peace, Brownwood DALLAS -- Dr. Jim spent the last few days of 14 -- Fall Festival, St. Boniface, August and most every Olfen. Denison, who pastored Midland’s First Baptist day of September writing 18 -- Celebration of White Mass about the deep meanings (for those in medical professions), Church from 1988-94, Sacred Heart Cathedral, San recently completed a of Mother Teresa’s book, Angelo, 6:30 p.m. nearly month-long study which is already being 21 -- Fall Festival, St. -

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H. Forensic Psychiatrist/Expert Witness

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H. Page 1 Forensic Psychiatrist/Expert Witness CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST/EXPERT WITNESS Diplomate, American Board of Psychiatry & Neurology www.expertwitnessforensicpsychiatrist.com 204 South Beverly Drive Suite 108 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 251-2866 LICENSURE (M.D.) New York - #128409 California - #A34122 Georgia - #072364 SPECIALTY BOARDS Diplomate, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology TRIAL TESTIMONY: QUALIFIED NATIONWIDE in: 1) Psychiatry 2) Media & Communications PRIOR HIGH PROFILE CASES include: California v. Eric Holder (alleged homicide of Nipsey Hussle) Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted homicide of autistic daughter) Florida v. Roman (teen felony bullying/attorney Jose Baez) California v. Redmond O’Neal (drug felony sentencing) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV→emotional distress) Terri Schiavo (appeal) Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz (Jenny Jones Talk Show Murder Trial) Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Vega, Rodriguez et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Jasmer v. Geraldo (emotional distress) Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H. Page 2 Forensic Psychiatrist/Expert Witness EXPERIENCE (20+ years) Track record of success in hundreds of civil & criminal cases in Federal, State & Administrative -

SMU's Knosl Wins US Amateur

VOLUME 93 TUESDAY ISSUE 6 AUGUST 28, 2007 ^ FIRST COPY roEE/ ADDITIONAL COPIES 50C , DALLAS, TEXAS • SMUDAILYCAMPOS.CQM By Russ Aaron said Addington, a victim of an on-cam- the solution," said Tieder. "This is some Chief Copy Editor pussexual assault She shared the story thing that'c4n,^ppra4o.My..9fiis."'--'. poses ofCAIR." [email protected] of her assault incident, which led to a Addtngton's first-hand experience left guidelines for pregnancy, citing Tieder as they key to her with the desire toget out and public lould not name First-year students filled the: major- coping, with the effects, The women, ly share her story with people who ihay gnificant justifi- ity of. seats in McParltn Auditorium regard having close relationships with not be familiar with the importance of femain sensitive last night for "Let's Talk About It," a friends a vital aspect of handling the preventing sexual assault. She and Heder tion interests of TODAY program that focuses on bringing the unexpected. believe that providing an understanding High 95, Low 75 issue of sexual assault to the forefront "Ourfriendship is the most important of sexual assault to students is crucial in TOMORROW of students' minds. Kelly Addington and part of what we do," said Tieder, urging making a difference. High 94, Low 76 Becca Tieder spoke to the students, about, students to be open with one another "You have to accept the things you the high frequency of sexual assaults on and to have someone to talk to in time cannot change and use them in your life of need. -

Atlantic News

ATLANTICNEWS.COM VOL 33, NO 46 | NOVEMBER 9, 2007 | ATLANTIC NEWS | PAGE 1A . INSIDE: 16 VOICES 26,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2007 Vol. 33 | No. 45 | 3 Sections | 32 Pages Having a ball with fun to spare Cyan Magenta Yellow Black BY LIZ PREMO ATlaNTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER HAMPTON | Some of Hampton’s Senior Citizens are having a ball going bowling, with nary a bowling ball in sight. In fact, there are no ten-pins, hardwood alleys or unfashionable bowling shoes in the picture either. That’s because this special group of participants is experiencing a whole new way to enjoy the game. BOWLING Continued on 26A• Small change, MINI VAN big difference SALE! 4 BEAUTIFUL BY SCOTT E. KINNEY MINIVANS EDITOR, 16 VOICES PRICED FROM EXETER | Some pennies, maybe a nickel and a couple of dimes mixed with a quarter $ or two. 4,995 BRING IN THIS AD They collect in a pocket somewhere until AND RECEIVE TO $ they make their way between the cushions $ 500 OFF of the sofa or are retrieved and placed on a 10,995 THE SELLING PRICE! dresser or in a change jar. GARYBLAKEMOTORCARS.COM But for years the children at Main Street 84 PORTSMOUTH AVE., EXETER, NH 03833 School have learned that little bit of change SHOWING RESPECT — Students at Main Street School in Exeter display the can make a big difference to those around the boxes they used to collect change for UNICEF, to help less fortunate children 866-838-3377 world. HOURS: MON-FRI: 8AM - 6PM • SAT: 9AM - 5PM around the globe. -

Reality Tv As Popular Science: the Making of a Genre

REALITY TV AS POPULAR SCIENCE: THE MAKING OF A GENRE by PAUL MYRON HILLIER (Under the Direction of James F. Hamilton) ABSTRACT This study addresses reality TV as popular science. Proposing that we might better understand this popular media form by locating it within a wider context, the project locates key traditions and practices that were drawn upon to help formulate reality TV in the United States in the history of social experiments. During the emergence of commercial forms of popular science in the nineteenth century, P.T. Barnum was an influential creator of a form of entertainment in which the object was to discern what was real in a manufactured amusement. By the 1950s and 1960s, both Candid Camera creator Allen Funt and behavioral psychologist Stanley Milgram formulated their projects as social experiments that placed unsuspecting people into carefully designed situations. Psychologist Phillip Zimbardo reconfigured social experiments in his Stanford prison experiment, paralleling similar uses in the public- television series An American Family, by studying social roles and types. All of these previous practices offered methods and rationales for what is known currently as reality TV, a genre that Mark Burnett helped develop by claiming to test and examine types of human behavior, and inform the ongoing making of a genre well-suited for the post- network era. Adding to more recent work of critical genre analysis, one of the contributions of this study is to explore social experiments as a genre. This study also documents the many characteristics shared by the scientific and commercial versions of social experiments, arguing that they have informed each other and have been responses to and products of the same social imperatives. -

Entertainment Or Exploitation?: Reality Television and the Inadequate Protection of Child Participants Under the Law

NOTES ENTERTAINMENT OR EXPLOITATION?: REALITY TELEVISION AND THE INADEQUATE PROTECTION OF CHILD PARTICIPANTS UNDER THE LAW CHRISTOPHER C. CIANCI* “Fame is a powerful ruler . There’s a societal structure that we’ve built, in part thanks to television, that says this is the thing you want, desire, and aim for. That’s a powerful lure for individuals in our society.”1 I. INTRODUCTION Reality shows have undoubtedly changed the business of television in America while also having an enormous effect on the American television- viewing experience. Considering the form’s immense success as a major— and recently crucial2—part of network programming over the last decade, reality programming has evolved past delivering content to a niche market of television viewers to now receiving mass, even global, appeal. Further, reality programs are still inexpensive to produce as compared to the production costs of scripted programs, a concept friendly to producers and to broadcasters, both nationally and internationally.3 While viewed as a natural money-maker by producers and production studios, reality television has been, and still is, a thorn in the side of the artist unions, like the Screen Actors Guild (“SAG”) and the Writers Guild of America (“WGA”),4 with producers of the genre continuing to dodge proper use of * J.D. Candidate, University of Southern California Law School, 2009. I would like to thank my Note advisor, Professor Heidi Rummel, for her guidance during this process. I also would like to thank my colleague and friend Stephanie Aldebot for her continued assistance and support. 1 Maria Elena Fernandez, Is Child Exploitation Legal in ‘Kid Nation’? CBS Faces Barrage of Questions on a Reality Show about Children Fending for Themselves, L.A. -

National the United States Played Tight De- Adults Who Smoke

C M Y K C13 DAILY 09-19-07 MD SU C13 CMYK The Washington Post S Wednesday, September 19, 2007 C13 ington sh p a Go around o w s . the world t . Today is the 25th birthday w with our c o w My Name Is of the smiley emoticon. m w :-) series. / k t i s d o s p WEATHER England on Saturday. Prevention. Yesterday the agency Tied with Washington were TODAY’S NEWS Yesterday’s game was played in announced a new, bilingual health San Francisco, California, and At- driving rain, the advance wave of campaign aimed at reducing kids’ lanta, Georgia. U.S. Team Advances a typhoon bearing down on exposure to secondhand smoke. Shanghai. Forecasters said it You Ready to Parrrty? In Women’s World Cup could be the worst typhoon to hit We’re No. 2! Arrrgh! K Today is one of K The U.S. women’s soccer team the area in a decade. K While you’re in the back seat KidsPost’s fa- is heading to the World Cup quar- watching a video or playing a vorite days terfinals, following its 1-0 victory Holy Smoke :-( game, do you ever think about of the year. over Nigeria yesterday. K Nearly 60 percent of kids ages 3 how much time your parents That’s be- TODAY: Sun and Lori Chalupny scored the goal to 11 are exposed to secondhand spend sitting in traffic? cause Sept. clouds. for the Americans, who are un- smoke. That means they breathe About 60 hours a year is the an- 19 is Inter- HIGH LOW defeated in their past 50 games.