Reality's Kids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

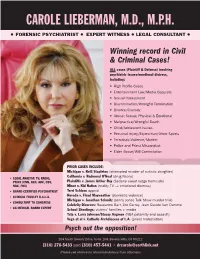

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. l FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST l EXPERT WITNESS l LEGAL CONSULTANT l Winning record in Civil & Criminal Cases! ALL cases (Plaintiff & Defense) involving psychiatric issues/emotional distress, including: • High Profile Cases • Entertainment Law/Media Copycats • Sexual Harassment • Discrimination/Wrongful Termination • Divorce/Custody • Abuse: Sexual, Physical & Emotional • Malpractice/Wrongful Death • Child/Adolescent issues • Personal Injury/Equestrian/Other Sports • Terrorism/Violence/Murder • Police and Priest Misconduct • Elder Abuse/Will Contestation PRIOR CASES INCLUDE: Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted murder of autistic daughter) California v. Redmond O’Neal • LEGAL ANALYST: TV, RADIO, (drug felony) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray PRINT (CNN, HLN, ABC, CBS, (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) NBC, FOX) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV → emotional distress) Terri Schiavo • BOARD CERTIFIED PSYCHIATRIST appeal Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather • CLINICAL FACULTY U.C.L.A. (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz • CONSULTANT TO CONGRESS (Jenny Jones Talk Show murder trial) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme • CA MEDICAL BOARD EXPERT School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Vega et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Psych out the opposition! 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108, Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 457-5441 [email protected] and • (Please see reverse for recommendations from attorneys) Here’s what your colleagues are saying about Carole Lieberman, M.D. Psychiatrist and Expert Witness: “I have had the opportunity to work with the “I have rarely had the good fortune to present best expert witnesses in the business, and I such well-considered testimony from such a would put Dr. -

Reality Programming Lessons for Twenty-First Century Trial Lawyering

Penn State Dickinson Law Dickinson Law IDEAS Faculty Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship Fall 2001 Reality Programming Lessons for Twenty-First Century Trial Lawyering Gary S. Gildin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/fac-works Recommended Citation Gary S. Gildin, Reality Programming Lessons for Twenty-First Century Trial Lawyering, 31 Stetson L. Rev. 61 (2001). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REALITY PROGRAMMING LESSONS FOR TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY TRIAL LAWYERING Gary S. Gildin* I. WHY SHO ULD WE CARE ABOUT THE ARRIVAL OF THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY? When I told my cousin-in-law Gary Ruben, a lawyer in Chicago, that I had agreed to write an article for a Symposium on trial advocacy in the twenty-first century, he responded incredulously, "We are supposed to be doing something different than trying to make a jury understand what happened and be persuaded by our version of the events?" Well, Gary, in one sense you are absolutely correct to be skeptical because the objectives of trial advocacy that you described have remained immutable, regardless of the century. However, two interrelated changes are occurring as we enter the new millennium that must affect the way trial lawyers present their cases to the jury - the evolution in the demographics of the jury pool and the revolution in technology that has transformed how our new breed of juror receives and is presented out-of-court informa- tion. -

Download Instructions on How to Hold an OEC Bottle and Can Drive

Hold Your Own Bottle and Can Drive to Support OEC Thank you for being a Bottle Bonanza drive sponsor! Many of your friends and neighbors separate their NYS redeemable water/soda/beer cans and bottles and return them periodically to a store or redemption center for cash. Some can’t be bothered and simply discard them. Collecting these items and redeeming them makes them donors and you a fundraiser for Onondaga Earth Corps. Here are some steps to take to hold a successful bottle and can drive: 1. Decide when and where you want to hold your drive. Some people hold them in their neighborhood at their own house and ask their neighbors and friends to drop off their donations. Others choose to pick up the donations at the source. Decide what’s right for you! 2. Contact Pieter Keese to schedule your drive and arrange any support you might need. [email protected] 315-289-6776 (phone or text) When texting state your name and Bottle Bonanza intention. 3. Hand out flyers a week or two before the drive. Download the fillable PDF flyer at the Bottle Bonanza website and complete it with your drive information for distribution in your neighborhood. Use your social media savvy to alert your friends. 4. Hold your drive 5. Take your collection to the redemption center (list provided below). 6. Advise the redemption center that the proceeds are for Onondaga Earth Corps. Let them know if you have to make more than one trip and they will credit the account until you have completed your delivery. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Oklahoma City Channel Lineup

Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Name Call Letters Number Fox College Sports - Central ** FCSC 648 Nicktoons NKTN 316 ActionMAX ACTMAX 835 Oklahoma City Fox College Sports - Pacific ** FCSP 649 Noggin NOG 320 Cinemax MAX 832 Fox Movie Channel FMC 792 Oxygen OXGN 368 Cinemax - West MAX-W 833 Fox News Channel FNC 210 PBS KIDS Sprout SPROUT 337 Encore ENC 932 Fox Reality Channel REAL 130 qubo qubo 328 Encore - West ENC-W 933 Channel Directory Fox Soccer Channel ** FSC 654 QVC QVC 197 Encore Action ENCACT 936 BY CHANNEL NAME Fox Sports en Español ** FSE 655 QVC QVC 420 Encore Drama ENCDRA 938 FSN Arizona ** FSAZ 762 Recorded TV Channel DVR 9999 Encore Love ENCLOV 934 FSN Detroit ** FSD 737 Sci Fi Channel SCIFI 151 Encore Mystery ENCMYS 935 Name Call Letters Number FSN Florida ** FSFL 720 Science Channel SCI 258 Encore Wam WAM 939 FSN Midwest ** FSMW 748 ShopNBC SHPNBC 424 Encore Westerns ENCWES 937 FSN North ** FSN 744 SiTV SiTV 194 FLIX FLIX 890 LOCAL LISTINGS FSN Northwest ** FSNW 764 Sleuth SLEUTH 161 HBO HBO 802 FSN Ohio-Cincinnati ** FSOHCI 732 Smile of a Child SMILE 340 HBO - West HBO-W 803 HSN HSN 8 FSN Ohio-Cleveland ** FSOHCL 734 SOAPnet SOAP 365 HBO Comedy HBOCOM 808 KAUT-43 (MY NETWORK TV) KAUT 43 FSN Pittsburgh ** FSP 730 SOAPnet - West SOAP-W 366 HBO Family HBOFAM 806 KETA-13 (PBS) KETA 13 FSN Prime Ticket ** FSPT 774 Speed Channel ** SPEED 652 HBO Latino HBOLAT 810 KFOR-4 (NBC) KFOR 4 FSN Rocky Mountain ** FSRM 760 Spike TV SPKE 145 HBO Signature HBOSIG 807 KOCB-34 (THE CW) KOCB 34 FSN South ** FSS 724 Spike -

Balloon Boy” Hoax, a Call to Regulate the Long-Ignored Issue of Parental Exploitation of Children

WHAT WILL IT TAKE?: IN THE WAKE OF THE OUTRAGEOUS “BALLOON BOY” HOAX, A CALL TO REGULATE THE LONG-IGNORED ISSUE OF PARENTAL EXPLOITATION OF CHILDREN RAMON RAMIREZ* I. INTRODUCTION On October 15, 2009, the world was captivated by the story of a little boy in peril as he allegedly floated through the Colorado sky in a homemade balloon.1 The boy’s parents, Richard and Mayumi Heene, first alerted authorities with an “emotional and desperate” 9-1-1 call, claiming that their son Falcon was in a balloon that had taken off from their backyard.2 Rescuers set out on a “frantic” ninety-minute chase that ended when the balloon “made a soft landing some 90 miles away;” but to their surprise, no one was in it.3 One of Falcon’s older brothers repeatedly said he saw Falcon get into the balloon before it took off, and a sheriff’s deputy said he saw something fall from the balloon while it was in the air, causing rescuers to fear the worst: Falcon fell out.4 The story appeared to have a happy ending after Falcon emerged from the family attic where he was hiding because his father yelled at him earlier in the day.5 That evening, the family appeared on Larry King Live on the Cable News Network (“CNN”) to tell their story, and when asked by his parents why he did not come out of the attic when they initially called for him, Falcon responded, “[y]ou guys said we did this for the show”; with that, suspicions began to arise.6 * J.D., University of Southern California Law School, 2011. -

Bonanza' Ranch Rides Into Pop Culture Sunset

Powered by SAVE THIS | EMAIL THIS | Close 'Bonanza' ranch rides into pop culture sunset INCLINE VILLAGE, Nevada (Reuters) -- A great symbol of the rugged old West, or at least as it was portrayed by Hollywood, is riding off into the sunset. The Ponderosa Ranch, an American West theme park where the television show "Bonanza" was filmed, closed Sunday after its sale to a financier whose plans for the property are unclear. The show, which ran on NBC from 1959 to 1973, was the top-rated U.S. program in the mid-1960s. Before the park closed, it was easy with a little imagination to feel transported there to a time when the American West was still a place to be tamed. Wranglers and a Stetson were proper attire. A sign outside the Silver Dollar Saloon welcomed ladies and not just the ones who earn a living upstairs. Fans of the long-running "Bonanza," which still airs on cable television, may recall Little Joe and Hoss getting the horses ready while Ben Cartwright yells from his office to see if the boys were doing what they were told in the 1860s West. "The house is the part I recognize -- the fireplace, the dining room, his office, the kitchen," said Oliver Barmann, 38, from Hessen, Germany, who visited the 570-acre grounds a week before the Ponderosa Ranch closed. "It's a pity it is closing," he said as his wife, Silvia, nodded in agreement. The property with postcard views of Lake Tahoe along Nevada's border with California became a theme park in the late 1960s, after the color-filmed scenes of "Bonanza"-- a first for a Western TV show in its day -- became part of American television lore. -

BONANZA G36 Specification and Description

BONANZA G36 Specifi cation and Description E-4063 THRU E-4080 Contents THIS DOCUMENT IS PUBLISHED FOR THE PURPOSE 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION ....................................2 OF PROVIDING GENERAL INFORMATION FOR THE 2. GENERAL ARRANGEMENT .................................3 EVALUATION OF THE DESIGN, PERFORMANCE AND EQUIPMENT OF THE BONANZA G36. IT IS NOT A 3. DESIGN WEIGHTS AND CAPACITIES ................4 CONTRACTUAL AGREEMENT UNLESS APPENDED 4. PERFORMANCE ..................................................4 TO AN AIRCRAFT PURCHASE AGREEMENT. 5. STRUCTURAL DESIGN CRITERIA ......................4 6. FUSELAGE ...........................................................4 7. WING .....................................................................5 8. EMPENNAGE .......................................................5 9. LANDING GEAR ...................................................5 10. POWERPLANT .....................................................5 11. PROPELLER .........................................................6 12. SYSTEMS .............................................................6 13. FLIGHT COMPARTMENT AND AVIONICS ...........7 14. INTERIOR ...........................................................12 15. EXTERIOR ..........................................................12 16. ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT .................................12 17. EMERGENCY EQUIPMENT ...............................12 18. DOCUMENTATION & TECH PUBLICATIONS ....13 19. MAINTENANCE TRACKING PROGRAM ...........13 20. NEW AIRCRAFT LIMITED WARRANTY .............13 -

Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: a Call for an Interstate Compact

Child and Family Law Journal Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 6 5-2021 Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Family Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation (2021) "Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact," Child and Family Law Journal: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Child and Family Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Cover Page Footnote J.D., Barry University, Dwayne O. Andreas School of Law, May 2022. I would like to thank my husband for supporting me during the many sleepless nights which led to the completion of this note. Thank you to my boys for always calling to check in and visiting often. Also, I wish to thank my Senior Editor for helping me to clarify the intention of my note. Finally, thank you to Professor Sonya Garza for her extensive comments and direction—I am truly humbled by the time you dedicated to my success. This article is available in Child and Family Law Journal: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol9/iss1/6 Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Tabetha Bennett* I. -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

Annual Report 2007 Creating and Distributing Top-Quality News, Sports and Entertainment Around the World

Annual Report 2007 Creating and distributing top-quality news, sports and entertainment around the world. News Corporation As of June 30, 2007 Filmed Entertainment WJBK Detroit, MI Latin America United States KRIV Houston, TX Cine Canal 33% Fox Filmed Entertainment KTXH Houston, TX Telecine 13% Twentieth Century Fox Film KMSP Minneapolis, MN Australia and New Zealand Corporation WFTC Minneapolis, MN Premium Movie Partnership 20% Fox 2000 Pictures WTVT Tampa Bay, FL Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Cable Network Programming Fox Atomic KUTP Phoenix, AZ United States Fox Music WJW Cleveland, OH FOX News Channel Twentieth Century Fox Home KDVR Denver, CO Fox Cable Networks Entertainment WRBW Orlando, FL FX Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WOFL Orlando, FL Fox Movie Channel and Merchandising KTVI St. Louis, MO Fox Regional Sports Networks Blue Sky Studios WDAF Kansas City, MO (15 owned and operated) (a) Twentieth Century Fox Television WITI Milwaukee, WI Fox Soccer Channel Fox Television Studios KSTU Salt Lake City, UT SPEED Twentieth Television WBRC Birmingham, AL FSN Regency Television 50% WHBQ Memphis, TN Fox Reality Asia WGHP Greensboro, NC Fox College Sports Balaji Telefilms 26% KTBC Austin, TX Fox International Channels Latin America WUTB Baltimore, MD Big Ten Network 49% Canal Fox WOGX Gainesville, FL Fox Sports Net Bay Area 40% Asia Fox Pan American Sports 38% Television STAR National Geographic Channel – United States STAR PLUS International 75% FOX Broadcasting Company STAR ONE National Geographic Channel – MyNetworkTV STAR -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto