Reality Programming Lessons for Twenty-First Century Trial Lawyering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

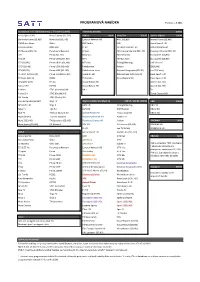

PROGRAMOVÁ NABÍDKA Platnost: 1.6.2021

PROGRAMOVÁ NABÍDKA Platnost: 1.6.2021 Pro začátek * KT 150 Kč (zdarma) / iTV 199 Kč ( 99 Kč) Tématické nabídky 270 Kč Arena Sport 2 HD Nova Cinema (SD, HD) Rodina 120 Kč Volný čas 120 Kč Sport a zábava 120 Kč Barrandov Krimi (SD,HD) Nova Gold (SD, HD) Cartoon Network HD AMC (SD,HD) Animal Planet (SD,HD) CNN Prima News Óčko CBS Reality AXN Arena Sport 1 HD Comedy House Óčko Star E! HD CS Film/CS Horror HD CNN International CS Mystery (SD,HD) Paramount Network JimJam Film Europe Channel (SD, HD) Discovery Channel (SD,HD) ČT1 Prima (SD, HD) Minimax Film+ (SD,HD) Eurosport 1 (SD,HD) ČT1 JM Prima COOL (SD, HD) MTV FilmBox Stars Eurosport 2 (SD,HD) ČT2 (SD,HD) Prima KRIMI (SD, HD) MTV 80s Fishing&Hunting Golf Channel ČT24 (SD,HD) Prima LOVE (SD, HD) Nickelodeon History ID(SD,HD) ČT3 (SD,HD) Prima MAX (SD, HD) Nickelodeon Junior National Geographic(SD,HD) Leo TV/Extasy ČT :D/ČT Art (SD,HD) Prima ZOOM (SD, HD) Spectrum HD National Geo Wild (SD,HD) Nova Sport 1 HD ČT Sport (SD,HD) REBEL TV Paprika Viasat Explore HD Nova Sport 2 HD Deutsche Welle RELAX Viasat History HD Sport 1 (SD, HD) Fashion TV RETRO Viasat Nature HD Sport 2 (SD, HD) FilmBox STV1 (Jednotka) HD VH 1 TLC France 24 STV2 (Dvojka) HD Travel Channel HD JOJ Family STV3 (Trojka) HD Kino Barrandov (SD,HD) Šlágr TV Mých 5 / Mých 10 / Mých 15 120 Kč / 220 Kč / 300 Kč HBO 200 Kč Mňam TV HD Šlágr 2 AMC HD Fishing&Hunting HBO HD Nasa TV TA3 HD AMS HD Golf Channel HBO 2 HD Noe TV Televize Seznam HD Animal Planet HD History Channel HBO 3 HD Nova (SD,HD) Televize Vysočina Discovery Channel HD Hustler TV Nova 2 (SD,HD) TV Barrandov (SD, HD) Discovery Science HD JimJam CINEMAX 50 Kč Nova Action (SD, HD) UP Network DTX HD JOJ Cinema (SD, HD) CINEMAX HD ID HD Leo TV/Extasy CINEMAX 2 HD DVB-T Arena Sport 1 HD Markíza Int. -

Elisa Elamus Ja Elisa Klassik Kanalipaketid Kanalid Seisuga 25.09.2021

Elisa Elamus ja Elisa Klassik kanalipaketid kanalid seisuga 25.09.2021 XL/XLK 99 telekanalit + 7 HD kanalit L/LK 99 telekanalit M/MK 61 telekanalit S/SK 40 telekanalit PROGRAMM KANAL AUDIO SUBTIITRID PROGRAMM KANAL AUDIO SUBTIITRID ETV 1 EST 3+ 66 RUS Kanal 2 2 EST STS 71 RUS TV3 3 EST Dom kino 87 RUS ETV2 4 EST TNT4 90 RUS TV6 5 EST TNT 93 RUS Duo4 6 EST Pjatnitsa 104 RUS Duo5 7 EST Kinokomedia HD 126 RUS Elisa 14 EST Eesti Kanal 150 EST Cartoon Network 17 ENG; RUS Meeleolukanal HD 300 EST KidZone TV 20 EST; RUS Euronews 704 RUS Euronews HD 21 ENG 3+ HD 931 RUS CNBC Europe 32 ENG TV6 HD 932 EST ALO TV 46 EST TV3 HD 933 EST MyHits HD 47 EST Duo7 HD 934 RUS Deutsche Welle 56 ENG Duo5 HD 935 EST ETV+ 59 RUS Duo4 HD 936 EST PBK 60 RUS Kanal 2 HD 937 EST RTR-Planeta 61 RUS ETV+ HD 938 RUS REN TV Estonia 62 RUS ETV2 HD 939 EST NTV Mir 63 RUS ETV HD 940 EST Fox Life 8 ENG; RUS EST Discovery Channel 37 ENG; RUS EST Fox 9 ENG; RUS EST BBC Earth HD 44 ENG-DD Duo3 10 ENG; RUS EST VH 1 48 ENG TLC 15 ENG; RUS EST TV 7 57 EST Nickelodeon 18 ENG; EST; RUS Orsent TV 69 RUS CNN 22 ENG TVN 70 RUS BBC World News 23 ENG 1+2 72 RUS Bloomberg TV 24 ENG Eurosport 1 HD 905 ENG; ENG-DD; RUS Eurosport 1 28 ENG; RUS Duo3 HD 917 ENG; RUS EST Viasat History 33 ENG; RUS EST; FIN; LAT Viasat History HD 919 ENG; RUS EST; FIN History 35 ENG; RUS EST Duo6 11 ENG; RUS EST Eurochannel HD 52 ENG EST FilmZone 12 ENG; RUS EST Life TV 58 RUS FilmZone+ 13 ENG; RUS EST TV XXI 67 RUS AMC 16 ENG; RUS Kanal Ju 73 RUS Pingviniukas 19 EST; RUS 24 Kanal 74 UKR HGTV HD 27 ENG EST Belarus -

MCPS TV Fpvs

MCPS Broadcast Blanket Distribution - TV FPV Rates paid April 2014 Non Peak Non Peak Progs Progs P(ence) P(ence) Peak FPV Non Peak (covered (covered Manufact Period Rate (per Rate (per (per FPV (per by by Source/S urer Source Link (YYMMYYM weighted weighted weighted weighted blanket blanket Licensee Channel Name hort Code udc Number Type code M) second) second) minute) minute) licence) licence) AATW Ltd Channel AKA CHNAKA S1759 287294 208 ot0 13091312 0 0.043 0 0.0258 Y Y BBC BBC 1 BBCTVD Z0003 5258 201 otc 13091312 75.452 37.726 45.2712 22.6356 Y Y BBC BBC 2 BBC2 Z0004 316168 201 otd 13091312 17.879 8.939 10.7274 5.3634 Y Y BBC BBC ALBA BBCALB Z0008 232662 201 oth 13091312 6.48 3.24 3.888 1.944 Y Y BBC BBC HD BBCHD Z0010 232654 201 otj 13091312 6.095 3.047 3.657 1.8282 Y Y BBC BBC Interactive BBCINT AN120 251209 201 or7 13091312 0 6.854 0 4.1124 Y Y BBC BBC News BBC NE Z0007 127284 201 otg 13091312 8.193 4.096 4.9158 2.4576 Y Y BBC BBC Parliament BBCPAR Z0009 316176 201 oti 13091312 13.414 6.707 8.0484 4.0242 Y Y BBC BBC Side Agreement for S4C BBCS4C Z0222 316184 201 oyb 13091312 15.495 7.747 9.297 4.6482 Y Y BBC BBC3 BBC3 Z0001 126187 201 ota 13091312 15.677 7.838 9.4062 4.7028 Y Y BBC BBC4 BBC4 Z0002 158776 201 otb 13091312 9.205 4.602 5.523 2.7612 Y Y BBC CBBC CBBC Z0005 165235 201 ote 13091312 8.96 4.48 5.376 2.688 Y Y BBC Cbeebies CBEEBI Z0006 285496 201 otf 13091312 12.457 6.228 7.4742 3.7368 Y Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Africa BBCENA Z0296 286601 201 ozu 13091312 1.91 0.955 1.146 0.573 N Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment -

Channel Guide July 2019

CHANNEL GUIDE JULY 2019 KEY HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET 1 PLAYER 1 MIXIT 1. Match your package 2. If there’s a tick in 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s to the column your column, you available as part of a 2 MIX 2 MAXIT get that channel Personal Pick collection 3 FUN PREMIUM CHANNELS 4 FULL HOUSE + PERSONAL PICKS 1 2 3 4 5 6 101 BBC One/HD* + 110 Sky One ENTERTAINMENT SPORT 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 100 Virgin Media Previews HD 501 Sky Sports Main Event HD 101 BBC One/HD* 502 Sky Sports Premier League HD 102 BBC Two HD 503 Sky Sports Football HD 103 ITV/STV HD* 504 Sky Sports Cricket HD 104 Channel 4 505 Sky Sports Golf HD 105 Channel 5 506 Sky Sports F1® HD 106 E4 507 Sky Sports Action HD 107 BBC Four HD 508 Sky Sports Arena HD 108 BBC One HD/BBC Scotland HD* 509 Sky Sports News HD 109 Sky One HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD + 110 Sky One 511 Sky Sports Main Event 111 Sky Witness HD 512 Sky Sports Premier League + 112 Sky Witness 513 Sky Sports Football 113 ITV HD* 514 Sky Sports Cricket 114 ITV +1 515 Sky Sports Golf 115 ITV2 516 Sky Sports F1® 116 ITV2 +1 517 Sky Sports Action 117 ITV3 518 Sky Sports Arena 118 ITV4 + 519 Sky Sports News 119 ITVBe + 520 Sky Sports Mix 120 ITVBe +1 + 521 Eurosport 1 HD + 121 Sky Two + 522 Eurosport 2 HD + 122 Sky Arts + 523 Eurosport 1 123 Pick + 524 Eurosport 2 + 124 GOLD HD 526 MUTV + 125 W 527 BT Sport 1 HD + 126 alibi 528 -

Voodoo Channel List

voodoo channel list ############################################################################## # English: 450-581 ############################################################################## # CBC HD Bravo USA CBS HF USA Space HD Global TV HD ABC HD USA AMC HD WPIX HD1 A/E USA LMN HD Fox HD USA Spike HD CNBC USA KTLA HD HIFI HD FX HD USA NBC HD CTV HD TNT HD E! HD SYFY HD USA Slice HD CP24 HD HBO HD Showcase HD Encore HD Showtime HD Start Movies HD Super CH 1 HD Super CH 2 HD TLC HD USA History HD USA History HD 2 National Geographic HD1 National Geographic USA Oasis HD Animal Planet HD USA Food Network HD USA HG TV USA Discovery HD USA Oasis Bloomberg HD USA CNN HD USA CNN Aljazeera English HLN Russia Today BBC News BBC 2 Bloomberg TV France 24 English Animal Planet Discovery Channel Discovery History Discovery Science Discovery History CBS Action CBS Drama CBS Reality Comedy Central Fashion TV Film4 Food Network FOX Investigation Discovery Lotus Movies MTV Music NASA TV Nat Geo Wild National Geographic Sky 2 Sky Living HYD Sky Movies Action Sky Movies Comedy Sky Movies Crime & Thriller Sky Movies Drama & Romance Sky Movies Family Sky Movies Premiere Sky Movies Sci-Fi & Horror Sky News Sky One SyFy Travel Channel True Movies 1, 2 UK Gold VH1 ############################################################################## # Sports: 600-643 ############################################################################## # TSN- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ESPN 2 USA NFL Network1 NBA TV Sportnet Ontario1 Sportnet World Sportnet 360 Tennis HD Sportsnet -

77.5 Hours of Original Primetime Programming 20.5 LGBT-Inclusive Hours

Network Responsibility Index Primetime Programming 2008-2009 A SPECIAL REPORT FROM THE GAY & LESBIAN ALLIANCE AGAINST DEFAMATION www.glaad.org Executive Summary The GLAAD Network Responsibility Index Eastern and Pacific (7:00 Central and Mountain) and ends at is an evaluation of the quantity and qual- 11:00 pm Eastern and Pacific (10:00 Central and Mountain), Monday through Saturday. On Sunday, primetime begins at ity of images of lesbian, gay, bisexual and 7:00 pm Eastern and Pacific (6:00 Central and Mountain). Wotransgenderrds (LGBT) people on television.and It Fox and TheImages CW do not air network programming during is intended to serve as a road map towards the last hour of primetime. increasing fair, accurate and inclusive LGBT media representations. The sampling of the 10 cable networks examined for the 2008-2009 report includes networks that appeared on Niels- GLAAD has seen time and time again how images of en Media Research’s list of top basic and premium cable multi-dimensional gay and transgender people on televi- networks as of June 2008. This list includes, alphabetically: sion have the power to change public perceptions. In A&E, FX, HBO, Lifetime, MTV, Sci Fi, Showtime, TBS, November 2008, GLAAD commissioned the Pulse of TNT and USA. The original primetime programs on these Equality Survey, conducted by Harris Interactive, which 10 networks were examined from June 1, 2008 – May 31, confirmed a growing trend toward greater acceptance 2009, for a combined total of 1,212.5 hours. Because of among the American public. Among the 19% who reported the re-airing and re-purposing of cable programming, only that their feelings toward gay and lesbian people have be- first-run broadcasts of original programs were counted when come more favorable over the past five years, 34% cited evaluating cable programming. -

CBS Primetime Sponsorship Opportunity 2021

CBS Primetime Sponsorship Opportunity 2021 Channel Investment Start Platforms On-air Social Online Competition The Opportunity Scheduling & Accreditation Sky Media and AMC Networks are excited to offer brands Primetime and advertisers the opportunity to sponsor primetime • 1800-2400 across CBS Justice, CBS Drama and CBS Reality. This • Approx. 540 hours per month package offers six hours a day across three channels of Approx. 4.320 sponsorship credits per month varied programming, from documentaries to docudramas, • from long-running serial dramas to classic cult series. • 15” Openers/Closers • 5” Break Bumpers (3 breaks per 1 hour show) About the Channels CBS Justice is one of the biggest general entertainment Example Programming channels in the country. Viewers will be thrilled by the twists and turns in these famous TV series such as NCIS CBS Justice CBS Reality and CSI Miami. Heroic characters from the many detective • The Fugitive • Judge Judy and action series on offer will wow an audience who • CSI Cyber • Evidence of Evil demand their TV with thrills. • Perry Mason • Murder Wall • NCIS • Fatal Vows CBS Reality is as unpredictable as real life. Be captivated, CBS Drama shocked and entertained by this award-winning channel, • Medium which brings you authentic criminal cases and • Father Dowling Mysteries investigations expertly dissected using cutting-edge • Perry Mason forensic technologies that will shock and challenge, inspire and motivate. Audiences may not have experienced the Online outrageous situations in Judge Judy, but they will certainly relate to the genuine human emotions shown. The drama doesn’t have to stop at on-air sponsorship. As part of any sponsorship campaign on the channels, CBS can offer online display media as added value. -

Trutv Freeview

Trutv freeview truTV is a larger-than-life entertainment channel that enthrals, engages and amuses with a mix of original, revealing and entertaining programmes featuring. truTV is a general entertainment channel on digital terrestrial free to air in the UK, with shows including Fear Factor, Container Wars, Redneck Island and Conan. TruTV is a British television channel owned by Sony Pictures Television. The channel launched free-to-air on Freeview, Freesat and Sky platforms on 4 August Freeview: Channel 68; Channel 69 (+1). TV channel: Tru TV +1, Freeview: 69, fSfS: Main TV channels. web, other, Freeview logo) · Freesat from Sky logo · Freesat logo · Tru TV +1, 69, Watch Tru TV Live Online Free channels streaming anywhere, UK for all your favourite reality based shows and sports. UK Freeview TV. Free-to-air broadcaster TruTV is under threat of closure if owner Turner only bother to venture so far down the Freeview EPG these days?Three Adult channels have closed on freeview. truTV channel every day, giving truTV prime access to Freeview viewers: where available, Made TV's channels are on Freeview channel 7 in. Watch Paranormal Survivor at 9pm every Wednesday from 10th February, new and exclusive to truTV (Freeview channel 68, Sky and. CBS Reality + truTV truTV + Horror Channel CBS Drama YourTV YourTV + Dave ja vu Blaze Freeview + Talking Pictures US reality TV channel TruTV is headed to Freeview, Freesat and YouView this Summer. The home of shows such as Fear Factor, Container. Our list of the digital TV channels available on Freeview. Our list includes the Freeview channel name, COM5. -

Usa Hd Channels Animal Planet Hd Abc News Hd Bein

USA HD CHANNELS ANIMAL PLANET HD MTV HD BEIN 6 HD UNIVISION DEPROTES HD ABC NEWS HD NBC HD BEIN 7 HD UNIVISION HD BEIN SPORTS HD NFL NETWORK HD BEIN 8 HD AMC HD BRAVO HD NFL NOW HD DIY NETWORK HD BBC AMERICA HD BTN HD NHL NETWORK HD E! HD BEN FC TV HD C-SPAN 1 HD NICK HD EL REY HD CINE SONY HD C-SPAN 2 HD NICK JR HD FOOD NETWORK HD CNBC HD C-SPAN 3 HD Nicktoons HD FOX CSA HD COZI HD CARTOON NETWORK HD PBS HD FOX CSC HD EL GOURMET HD CBN HD Reelz HD FOX CSP HD FIGHT NETWORK HD CBN NEWS HD SEC NETWORK1679.ts FOX DEPORTES HD FNTSY SPORTS NETWORK FHD CBS SPORTS NETWORK HD SHOWTIME HD FOX SPORTS SOCCER PLUS HD FOX LIFE HD CBSN HD SN CENTRAL HD FUSE HD IFC HD Cinemax Action Max HD SPIKE HD FUSION HD MAS CHIC HD CINEMAX HD STARZ EAST HD FX HD MAVTV HD Cinemax Thriller Max HD Starz Edge HD FXM HD MOTORSPORTS TV HD COMEDY CENTRAL HD Starz HD FXX HD NAT GEO MUNDO HD CW HD Starz Kids & Family HD FYI HD NBC SPORTS PLUS CHICAGO HD Destination America HD SYFY HD GALAVISION HD OUTDOOR HD DISCOVERY HD TBS HD GOL TV EN HD OUTSIDE TV HD DISCOVERY SCIENCE HD TENNIS HD GOL TV HD RTP INTERNATIONAL HD DISCOVERY VELOCITY HD THE WEATHER CHANNEL HD HALLMARK MOVIE HD SPORTS ILLUSTRATED (SITV) HD Disney HD TNT HD HISTORY HD SPORTS MAN HD ESPN HD TRAVEL CHANNEL HD LIFETIME HD SUNDANCE HD ESPN NEWS HD TRU TV HD LMN HD WE TV HD ESPN U HD TV LAND HD MSNBC HD WETV HD ESPN 2 HD UNIVERSAL HD NAT GEO EAST HD WL NY HD FOX BUSINESS NETWORK HD UNIVISION DEP HD NAT GEO WILD HD WORLD FISHING NETWORK HD FOX HD USA NETWORK HD NBC SPORTS CHICAGO HD STADIUM HD FOX NEWS HD VH1 HD -

Television Programs Filmed in Hawaii ______High-Lighting Just Some of the Many Shows Shot in Hawaii

FilmHawaii HAWAII FILM OFFICE | State of Hawaii, Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism| 250 South Hotel St., 5th Floor | Honolulu, HI 96813 Mailing Address: P.O. Box 2359 | Honolulu, HI 96804 | Phone (808) 586-2570 | Fax (808) 586-2572 | [email protected] Television Programs Filmed in Hawaii ______________________________________________ High-lighting just some of the many shows shot in Hawaii 2011 The River (ABC) TV Series - A riveting new thriller starring Bruce Greenwood as Dr. Emmet Cole, Executive producers: Michael Green, Oren Peli, Zack Estrin, Jason Blum and Steven Schneider. Oahu HAWAII FIVE-0 (CBS TV Studios) TV Series - one of the most iconic shows in television history. Executive Producer/Writer Peter Lenkov, Executive Producers Alex Kurtzman and Robert Orci. Currently filming Season 2. Oahu DOG: THE BOUNTY HUNTER (A&E) Reality TV series featuring the colorful adventures of a local bounty hunter. Oahu. OFF THE MAP (Touchstone Television / ABC) TV Series - Executive producers Shonda Rhimes and Betsy Beers: 2011 on ABC network television. Oahu ROSEANNE’S NUTS (A&E) – Realty TV on Roseanne Barr’s life on her Macadamia nut farm. Big Island FLY FISHING THE WORLD (Outdoor Channel) is a weekly program featuring a celebrity guest who, with the show's creator and host, John Barrett, fly-fishes and enjoys some of the most beautiful and unique waters this world has to offer. Oahu and Molokai WEDDING WARS (MTV Networks) Twelve engaged couples touch down at the luxurious Turtle Bay resort in Hawaii, ready to battle it out for a $100,000 dream destination wedding and a $25,000 nest egg.