Entertainment Or Exploitation?: Reality Television and the Inadequate Protection of Child Participants Under the Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beckett & Aesthetics

09/25/21 Beckett & Aesthetics | Goldsmiths, University of London Beckett & Aesthetics View Online 1. Beckett, S.: Watt. John Calder, London (1963). 2. Connor, S.: ‘Shifting Ground: Beckett and Nauman’, http://www.stevenconnor.com/beckettnauman/. 3. Tubridy, D.: ‘Beckett’s Spectral Silence: Breath and the Sublime’. 1, 102–122 (2010). 4. Lyotard, J.F., Bennington, G., Bowlby, R.: ‘After the Sublime, the State of Aesthetics’. In: The inhuman: reflections on time. Polity, Cambridge (1991). 5. Lyotard, J.-F.: The Sublime and the Avant-Garde. In: The inhuman: reflections on time. pp. 89–107. Polity, Cambridge (1991). 6. Krauss, R.: LeWitt’s Ark. October. 121, 111–113 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1162/octo.2007.121.1.111. 1/4 09/25/21 Beckett & Aesthetics | Goldsmiths, University of London 7. Simon Critchley: Who Speaks in the Work of Samuel Beckett? Yale French Studies. 114–130 (1998). 8. Kathryn Chiong: Nauman’s Beckett Walk. October. 86, 63–81 (1998). 9. Deleuze, G.: ‘He Stuttered’. In: Essays critical and clinical. pp. 107–114. Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis (1997). 10. Deleuze, G., Smith, D.W.: ‘The Greatest Irish Film (Beckett’s ‘Film’)’. In: Essays critical and clinical. pp. 23–26. Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis (1997). 11. Adorno, T.: ‘Trying to Understand Endgame’. In: Samuel Beckett. pp. 39–49. Longman, New York (1999). 12. Laws, C.: ‘Morton Feldman’s Neither: A Musical Translation of Beckett’s Text'. In: Samuel Beckett and music. pp. 57–85. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1998). 13. Cage, J.: ‘The Future of Music: Credo’. In: Audio culture: readings in modern music. pp. 25–28. -

This Item Is the Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version Of

This item is the archived peer-reviewed author-version of: Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Reference: Van Hulle Dirk, Kestemont Mike.- Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Style - ISSN 0039-4238 - 50:2(2016), p. 172-202 Full text (Publisher's DOI): https://doi.org/10.1353/STY.2016.0003 To cite this reference: http://hdl.handle.net/10067/1382770151162165141 Institutional repository IRUA This is the author’s version of an article published by the Pennsylvania State University Press in the journal Style 50.2 (2016), pp. 172-202. Please refer to the published version for correct citation and content. For more information, see http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.50.2.0172?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. <CT>Periodizing Samuel Beckett’s Works: A Stylochronometric Approach1 <CA>Dirk van Hulle and Mike Kestemont <AFF>UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP <abs>ABSTRACT: We report the first analysis of Samuel Beckett’s prose writings using stylometry, or the quantitative study of writing style, focusing on grammatical function words, a linguistic category that has seldom been studied before in Beckett studies. To these function words, we apply methods from computational stylometry and model the stylistic evolution in Beckett’s oeuvre. Our analyses reveal a number of discoveries that shed new light on existing periodizations in the secondary literature, which commonly distinguish an “early,” “middle,” and “late” period in Beckett’s oeuvre. We analyze Beckett’s prose writings in both English and French, demonstrating notable symmetries and asymmetries between both languages. The analyses nuance the traditional three-part periodization as they show the possibility of stylistic relapses (disturbing the linearity of most periodizations) as well as different turning points depending on the language of the corpus, suggesting that Beckett’s English oeuvre is not identical to his French oeuvre in terms of patterns of stylistic development. -

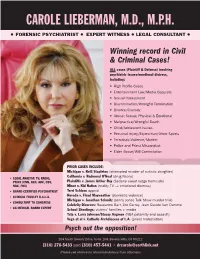

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. l FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST l EXPERT WITNESS l LEGAL CONSULTANT l Winning record in Civil & Criminal Cases! ALL cases (Plaintiff & Defense) involving psychiatric issues/emotional distress, including: • High Profile Cases • Entertainment Law/Media Copycats • Sexual Harassment • Discrimination/Wrongful Termination • Divorce/Custody • Abuse: Sexual, Physical & Emotional • Malpractice/Wrongful Death • Child/Adolescent issues • Personal Injury/Equestrian/Other Sports • Terrorism/Violence/Murder • Police and Priest Misconduct • Elder Abuse/Will Contestation PRIOR CASES INCLUDE: Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted murder of autistic daughter) California v. Redmond O’Neal • LEGAL ANALYST: TV, RADIO, (drug felony) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray PRINT (CNN, HLN, ABC, CBS, (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) NBC, FOX) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV → emotional distress) Terri Schiavo • BOARD CERTIFIED PSYCHIATRIST appeal Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather • CLINICAL FACULTY U.C.L.A. (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz • CONSULTANT TO CONGRESS (Jenny Jones Talk Show murder trial) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme • CA MEDICAL BOARD EXPERT School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Vega et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Psych out the opposition! 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108, Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 457-5441 [email protected] and • (Please see reverse for recommendations from attorneys) Here’s what your colleagues are saying about Carole Lieberman, M.D. Psychiatrist and Expert Witness: “I have had the opportunity to work with the “I have rarely had the good fortune to present best expert witnesses in the business, and I such well-considered testimony from such a would put Dr. -

Samuel Beckett's Peristaltic Modernism, 1932-1958 Adam

‘FIRST DIRTY, THEN MAKE CLEAN’: SAMUEL BECKETT’S PERISTALTIC MODERNISM, 1932-1958 ADAM MICHAEL WINSTANLEY PhD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE MARCH 2013 1 ABSTRACT Drawing together a number of different recent approaches to Samuel Beckett’s studies, this thesis examines the convulsive narrative trajectories of Beckett’s prose works from Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1931-2) to The Unnamable (1958) in relation to the disorganised muscular contractions of peristalsis. Peristalsis is understood here, however, not merely as a digestive process, as the ‘propulsive movement of the gastrointestinal tract and other tubular organs’, but as the ‘coordinated waves of contraction and relaxation of the circular muscle’ (OED). Accordingly, this thesis reconciles a number of recent approaches to Beckett studies by combining textual, phenomenological and cultural concerns with a detailed account of Beckett’s own familiarity with early twentieth-century medical and psychoanalytical discourses. It examines the extent to which these discourses find a parallel in his work’s corporeal conception of the linguistic and narrative process, where the convolutions, disavowals and disjunctions that function at the level of narrative and syntax are persistently equated with medical ailments, autonomous reflexes and bodily emissions. Tracing this interest to his early work, the first chapter focuses upon the masturbatory trope of ‘dehiscence’ in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, while the second examines cardiovascular complaints in Murphy (1935-6). The third chapter considers the role that linguistic constipation plays in Watt (1941-5), while the fourth chapter focuses upon peristalsis and rumination in Molloy (1947). The penultimate chapter examines the significance of epilepsy, dilation and parturition in the ‘throes’ that dominate Malone Dies (1954-5), whereas the final chapter evaluates the significance of contamination and respiration in The Unnamable (1957-8). -

I:\28947 Ind Law Rev 47-1\47Masthead.Wpd

CITIGROUP: A CASE STUDY IN MANAGERIAL AND REGULATORY FAILURES ARTHUR E. WILMARTH, JR.* “I don’t think [Citigroup is] too big to manage or govern at all . [W]hen you look at the results of what happened, you have to say it was a great success.” Sanford “Sandy” Weill, chairman of Citigroup, 1998-20061 “Our job is to set a tone at the top to incent people to do the right thing and to set up safety nets to catch people who make mistakes or do the wrong thing and correct those as quickly as possible. And it is working. It is working.” Charles O. “Chuck” Prince III, CEO of Citigroup, 2003-20072 “People know I was concerned about the markets. Clearly, there were things wrong. But I don’t know of anyone who foresaw a perfect storm, and that’s what we’ve had here.” Robert Rubin, chairman of Citigroup’s executive committee, 1999- 20093 “I do not think we did enough as [regulators] with the authority we had to help contain the risks that ultimately emerged in [Citigroup].” Timothy Geithner, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2003-2009; Secretary of the Treasury, 2009-20134 * Professor of Law and Executive Director of the Center for Law, Economics & Finance, George Washington University Law School. I wish to thank GW Law School and Dean Greg Maggs for a summer research grant that supported my work on this Article. I am indebted to Eric Klein, a member of GW Law’s Class of 2015, and Germaine Leahy, Head of Reference in the Jacob Burns Law Library, for their superb research assistance. -

Beckett and Nothing with the Negative Spaces of Beckett’S Theatre

8 Beckett, Feldman, Salcedo . Neither Derval Tubridy Writing to Thomas MacGreevy in 1936, Beckett describes his novel Murphy in terms of negation and estrangement: I suddenly see that Murphy is break down [sic] between his ubi nihil vales ibi nihil velis (positive) & Malraux’s Il est diffi cile à celui qui vit hors du monde de ne pas rechercher les siens (negation).1 Positioning his writing between the seventeenth-century occasion- alist philosophy of Arnold Geulincx, and the twentieth-century existential writing of André Malraux, Beckett gives us two visions of nothing from which to proceed. The fi rst, from Geulincx’s Ethica (1675), argues that ‘where you are worth nothing, may you also wish for nothing’,2 proposing an approach to life that balances value and desire in an ethics of negation based on what Anthony Uhlmann aptly describes as the cogito nescio.3 The second, from Malraux’s novel La Condition humaine (1933), contends that ‘it is diffi cult for one who lives isolated from the everyday world not to seek others like himself’.4 This chapter situates its enquiry between these poles of nega- tion, exploring the interstices between both by way of neither. Drawing together prose, music and sculpture, I investigate the role of nothing through three works called neither and Neither: Beckett’s short text (1976), Morton Feldman’s opera (1977), and Doris Salcedo’s sculptural installation (2004).5 The Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s work explores the politics of absence, par- ticularly in works such as Unland: Irreversible Witness (1995–98), which acts as a sculptural witness to the disappeared victims of war. -

Balloon Boy” Hoax, a Call to Regulate the Long-Ignored Issue of Parental Exploitation of Children

WHAT WILL IT TAKE?: IN THE WAKE OF THE OUTRAGEOUS “BALLOON BOY” HOAX, A CALL TO REGULATE THE LONG-IGNORED ISSUE OF PARENTAL EXPLOITATION OF CHILDREN RAMON RAMIREZ* I. INTRODUCTION On October 15, 2009, the world was captivated by the story of a little boy in peril as he allegedly floated through the Colorado sky in a homemade balloon.1 The boy’s parents, Richard and Mayumi Heene, first alerted authorities with an “emotional and desperate” 9-1-1 call, claiming that their son Falcon was in a balloon that had taken off from their backyard.2 Rescuers set out on a “frantic” ninety-minute chase that ended when the balloon “made a soft landing some 90 miles away;” but to their surprise, no one was in it.3 One of Falcon’s older brothers repeatedly said he saw Falcon get into the balloon before it took off, and a sheriff’s deputy said he saw something fall from the balloon while it was in the air, causing rescuers to fear the worst: Falcon fell out.4 The story appeared to have a happy ending after Falcon emerged from the family attic where he was hiding because his father yelled at him earlier in the day.5 That evening, the family appeared on Larry King Live on the Cable News Network (“CNN”) to tell their story, and when asked by his parents why he did not come out of the attic when they initially called for him, Falcon responded, “[y]ou guys said we did this for the show”; with that, suspicions began to arise.6 * J.D., University of Southern California Law School, 2011. -

Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: a Call for an Interstate Compact

Child and Family Law Journal Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 6 5-2021 Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Family Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation (2021) "Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact," Child and Family Law Journal: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Child and Family Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Cover Page Footnote J.D., Barry University, Dwayne O. Andreas School of Law, May 2022. I would like to thank my husband for supporting me during the many sleepless nights which led to the completion of this note. Thank you to my boys for always calling to check in and visiting often. Also, I wish to thank my Senior Editor for helping me to clarify the intention of my note. Finally, thank you to Professor Sonya Garza for her extensive comments and direction—I am truly humbled by the time you dedicated to my success. This article is available in Child and Family Law Journal: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol9/iss1/6 Child Entertainers and Their Limited Protections: A Call For an Interstate Compact Tabetha Bennett* I. -

Samuel Beckett and Intermedial Performance: Passing Between

Samuel Beckett and intermedial performance: passing between Article Accepted Version McMullan, A. (2020) Samuel Beckett and intermedial performance: passing between. Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, 32 (1). pp. 71-85. ISSN 0927-3131 doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/18757405-03201006 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/85561/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/18757405-03201006 Publisher: Brill All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Samuel Beckett and Intermedial Performance: Passing Between Anna McMullan Professor in Theatre, University of Reading [email protected] This article analyses two intermedial adaptations of works by Beckett for performance in relation to Ágnes Petho’s definition of intermediality as a border zone or passageway between media, grounded in the “inter-sensuality of perception”. After a discussion of how Beckett’s own practice might be seen as intermedial, the essay analyses the 1996 American Repertory Company programme Beckett Trio, a staging of three of Beckett’s television plays which incorporated live camera projected onto a large screen in a television studio. The second case study analyses Company SJ’s 2014 stage adaptation of a selection of Beckett’s prose texts, Fizzles, in a historic site-specific location in inner city Dublin, which incorporated projected sequences previously filmed in a different location. -

Katharine Worth Collection MS 5531

University Museums and Special Collections Service Katharine Worth Collection MS 5531 Production design material for the 1955 Waiting for Godot set by Peter Snow - including a model of the set; theatre memorabilia, correspondence, notes of Katharine Worth; Beckett related VHS and cassette tapes. The Collection covers the year’s 20th century. The physical extent of the collection is 5 boxes and 5 framed prints. MS 5531 A Research files 1950s-1990s MS 5531 A/1 Folder of research entitled Beckett Festival Dublin 1991 1991 Includes press cutting, press release, letters relating to the festival 1 folder Katharine Worth gave a lecture Beckett's Ghost, with C.V. for Katharine Worth and Julian Curry MS 5531 A/2 Folders of research entitled Beckett and Music 1980s-1995 Includes hand written notes and typed notes made by Katharine Worth and correspondence relating to her Samuel Beckett and Music article 2 folders MS 5531 A/3 Folders of research entitled Cascando 1981-1984 Includes letter from David Warrilow, annotated script for Cascando, 5 black and white photographs of a production, correspondence relating to the production of Cascando by Katharine Worth and David Clark of the University of London Audio-Visual Centre and some handwritten notes 2 folders MS 5531 A/4 Folders relating to Company 1989-1991 Includes Mise en Scene by Pierre Chabert for his stage adaptation of Compagnie [in French], correspondence relating to Page 1 of 13 University Museums and Special Collections Service a proposed production of Company by Katharine Worth and Iambic -

Patrolling the Homefront: the Emotional Labor of Army Wives Volunteering in Family Readiness Groups

PATROLLING THE HOMEFRONT: THE EMOTIONAL LABOR OF ARMY WIVES VOLUNTEERING IN FAMILY READINESS GROUPS By Copyright 2010a Jaime Nicole Noble Gassmann B.A., Southern Methodist University, 2002 M.A., University of Kansas, 2004 Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chairperson: _________________________________ Brian Donovan Committee Members: _________________________________ Norman R. Yetman _________________________________ Robert J. Antonio _________________________________ Joane Nagel _________________________________ Ben Chappell Date Defended: 30 August 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Jaime Nicole Noble Gassmann certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PATROLLING THE HOMEFRONT: THE EMOTIONAL LABOR OF ARMY WIVES VOLUNTEERING IN FAMILY READINESS GROUPS By Jaime Nicole Noble Gassmann Chairperson: _________________________________ Brian Donovan Committee Members: _________________________________ Norman R. Yetman _________________________________ Robert J. Antonio _________________________________ Joane Nagel _________________________________ Ben Chappell Date Approved: 30 August 2010 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the emotional labor of Army wives as they volunteer in Army-mandated family-member support groups in each unit called Family Readiness Groups (FRGs). Since its inception, the Army has relied unofficially on soldiers’ wives’ contributions to the success of their husbands’ careers in a two-for-one career pattern—two workers for one paycheck. The Army made such expectations official when in 1988 it began to require volunteer labor to run each unit’s FRG. The Army tasks FRGs with connecting members to resources and relaying official information to soldiers’ family members. These support groups also serve a vital socializing function, though not all soldiers’ spouses participate in the information-dispensing and community-building groups. -

New Jersey Department of Children and Families Licensed Child Care Centers As of July 2014

New Jersey Department of Children and Families Licensed Child Care Centers as of July 2014 COUNTY CITY CENTER ADDR1 ADDR2 ZIP PHONE AGES CAPACITY Absecon Nursery Atlantic Absecon School Church St & Pitney Rd 08201 (609) 646-6940 2½ to 6 42 All God's Children Atlantic ABSECON Daycare/PreSchool 515 S MILL RD 08201 (609) 645-3363 0 to 13 75 Alphabet Alley Nursery Atlantic ABSECON School 208 N JERSEY AVE 08201 (609) 457-4316 2½ to 6 15 Atlantic ABSECON KidAcademy 101 MORTON AVE 08201 (609) 646-3435 0 to 13 120 682 WHITE HORSE Atlantic ABSECON Kidz Campus PIKE 08201 (609) 385-0145 0 to 13 72 Mrs. Barnes Play House 202-208 NEW JERSEY Atlantic ABSECON Day Care, LLC AVENUE 08201 (609) 377-8417 2½ to 13 30 Tomorrows Leaders Childcare/Learning 303 NEW JERSEY Atlantic ABSECON Center AVENUE 08201 (609) 748-3077 2½ to 13 30 Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Adventures In Learning 1812 MARMORA AVE 08401 (609) 348-3883 0 to 13 50 Atlantic Care After School Kids - Uptown Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Center 323 MADISON AVE 08401 (609) 345-1994 6 to 13 60 Atlantic City Day Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Nursery 101 N BOSTON AVE 08401 (609) 345-3569 0 to 6 87 Atlantic City High 1400 NORTH ALBANY Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY School Head Start AVENUE 08401 (609) 385-9471 0 to 6 30 AtlantiCare Dr. Martin L. Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY King Jr. Family Center 1700 MARMORA AVE 08401 (609) 344-3111 6 to 13 60 AtlantiCare New York Atlantic ATLANTIC CITY Avenue Family Center 411 N NEW YORK AVE ROOM 224 08401 (609) 441-0102 6 to 13 60 Little Flyers Academy FAA WILLIAM J.