Samuel Beckett and Intermedial Performance: Passing Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beckett & Aesthetics

09/25/21 Beckett & Aesthetics | Goldsmiths, University of London Beckett & Aesthetics View Online 1. Beckett, S.: Watt. John Calder, London (1963). 2. Connor, S.: ‘Shifting Ground: Beckett and Nauman’, http://www.stevenconnor.com/beckettnauman/. 3. Tubridy, D.: ‘Beckett’s Spectral Silence: Breath and the Sublime’. 1, 102–122 (2010). 4. Lyotard, J.F., Bennington, G., Bowlby, R.: ‘After the Sublime, the State of Aesthetics’. In: The inhuman: reflections on time. Polity, Cambridge (1991). 5. Lyotard, J.-F.: The Sublime and the Avant-Garde. In: The inhuman: reflections on time. pp. 89–107. Polity, Cambridge (1991). 6. Krauss, R.: LeWitt’s Ark. October. 121, 111–113 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1162/octo.2007.121.1.111. 1/4 09/25/21 Beckett & Aesthetics | Goldsmiths, University of London 7. Simon Critchley: Who Speaks in the Work of Samuel Beckett? Yale French Studies. 114–130 (1998). 8. Kathryn Chiong: Nauman’s Beckett Walk. October. 86, 63–81 (1998). 9. Deleuze, G.: ‘He Stuttered’. In: Essays critical and clinical. pp. 107–114. Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis (1997). 10. Deleuze, G., Smith, D.W.: ‘The Greatest Irish Film (Beckett’s ‘Film’)’. In: Essays critical and clinical. pp. 23–26. Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis (1997). 11. Adorno, T.: ‘Trying to Understand Endgame’. In: Samuel Beckett. pp. 39–49. Longman, New York (1999). 12. Laws, C.: ‘Morton Feldman’s Neither: A Musical Translation of Beckett’s Text'. In: Samuel Beckett and music. pp. 57–85. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1998). 13. Cage, J.: ‘The Future of Music: Credo’. In: Audio culture: readings in modern music. pp. 25–28. -

This Item Is the Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version Of

This item is the archived peer-reviewed author-version of: Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Reference: Van Hulle Dirk, Kestemont Mike.- Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Style - ISSN 0039-4238 - 50:2(2016), p. 172-202 Full text (Publisher's DOI): https://doi.org/10.1353/STY.2016.0003 To cite this reference: http://hdl.handle.net/10067/1382770151162165141 Institutional repository IRUA This is the author’s version of an article published by the Pennsylvania State University Press in the journal Style 50.2 (2016), pp. 172-202. Please refer to the published version for correct citation and content. For more information, see http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.50.2.0172?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. <CT>Periodizing Samuel Beckett’s Works: A Stylochronometric Approach1 <CA>Dirk van Hulle and Mike Kestemont <AFF>UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP <abs>ABSTRACT: We report the first analysis of Samuel Beckett’s prose writings using stylometry, or the quantitative study of writing style, focusing on grammatical function words, a linguistic category that has seldom been studied before in Beckett studies. To these function words, we apply methods from computational stylometry and model the stylistic evolution in Beckett’s oeuvre. Our analyses reveal a number of discoveries that shed new light on existing periodizations in the secondary literature, which commonly distinguish an “early,” “middle,” and “late” period in Beckett’s oeuvre. We analyze Beckett’s prose writings in both English and French, demonstrating notable symmetries and asymmetries between both languages. The analyses nuance the traditional three-part periodization as they show the possibility of stylistic relapses (disturbing the linearity of most periodizations) as well as different turning points depending on the language of the corpus, suggesting that Beckett’s English oeuvre is not identical to his French oeuvre in terms of patterns of stylistic development. -

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra Anglického Jazyka a Literatury

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury AXIOLOGICAL DYNAMICS IN SAMUEL BECKETT'S PLAYS Diplomová práce Brno 2015 Autor práce: Vedoucí práce: Bc. Monika Chmelařová Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk Anotace Předmětem diplomové práce Axiologické proměny v dramatickém díle Samuela Becketta je analýza Beckettových her s tematicky vyměřenou interpretací za účelem stanovení prvků v axiologické rovině. Stěžejním cílem práce je vymezení klíčových hodnot v autorově dramatické tvorbě, obsáhnutí charakteru a stimulů axiologické dynamiky. Práce je založena na kritickém zhodnocení autobiografie a vývoje hodnotové orientace Samuela Becketta na poli osobním i autorském, a to při posouzení vývoje hodnot již od počátku autorova života a tvorby. Beckettovy hry jsou výsledkem již vlastní specifické poetiky; práce si dává za cíl sledovat, co přispělo k jejímu utvoření, jaké hodnoty jsou v jeho dramatu zastoupeny a jakým způsobem se jeho dramatická tvorba axiologicky vyvíjí. Výstupem práce je kritický pohled na co nejkomplexnější autorovo dramatické dílo z pohledu hodnot a stanovení příčin těchto proměn, a to v tematicko-komparativním a diachronním (tj. chronologickém) pojetí. Abstract The subject of the diploma thesis Axiological Dynamics in Samuel Beckett's Plays is a thematically determined interpretation with the intention to determine features within the axiological level. The crucial part of the thesis is the determination of significant values in author's dramatic works, characterization of nature and stimuli of axiological dynamics. The thesis is based on critical evaluation of autobiography and development of value orientation of Samuel Beckett in private and authorial fields, i. e. with consideration of the development of values from the beginning of author's life and work. -

Samuel Beckett's Peristaltic Modernism, 1932-1958 Adam

‘FIRST DIRTY, THEN MAKE CLEAN’: SAMUEL BECKETT’S PERISTALTIC MODERNISM, 1932-1958 ADAM MICHAEL WINSTANLEY PhD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE MARCH 2013 1 ABSTRACT Drawing together a number of different recent approaches to Samuel Beckett’s studies, this thesis examines the convulsive narrative trajectories of Beckett’s prose works from Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1931-2) to The Unnamable (1958) in relation to the disorganised muscular contractions of peristalsis. Peristalsis is understood here, however, not merely as a digestive process, as the ‘propulsive movement of the gastrointestinal tract and other tubular organs’, but as the ‘coordinated waves of contraction and relaxation of the circular muscle’ (OED). Accordingly, this thesis reconciles a number of recent approaches to Beckett studies by combining textual, phenomenological and cultural concerns with a detailed account of Beckett’s own familiarity with early twentieth-century medical and psychoanalytical discourses. It examines the extent to which these discourses find a parallel in his work’s corporeal conception of the linguistic and narrative process, where the convolutions, disavowals and disjunctions that function at the level of narrative and syntax are persistently equated with medical ailments, autonomous reflexes and bodily emissions. Tracing this interest to his early work, the first chapter focuses upon the masturbatory trope of ‘dehiscence’ in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, while the second examines cardiovascular complaints in Murphy (1935-6). The third chapter considers the role that linguistic constipation plays in Watt (1941-5), while the fourth chapter focuses upon peristalsis and rumination in Molloy (1947). The penultimate chapter examines the significance of epilepsy, dilation and parturition in the ‘throes’ that dominate Malone Dies (1954-5), whereas the final chapter evaluates the significance of contamination and respiration in The Unnamable (1957-8). -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

I:\28947 Ind Law Rev 47-1\47Masthead.Wpd

CITIGROUP: A CASE STUDY IN MANAGERIAL AND REGULATORY FAILURES ARTHUR E. WILMARTH, JR.* “I don’t think [Citigroup is] too big to manage or govern at all . [W]hen you look at the results of what happened, you have to say it was a great success.” Sanford “Sandy” Weill, chairman of Citigroup, 1998-20061 “Our job is to set a tone at the top to incent people to do the right thing and to set up safety nets to catch people who make mistakes or do the wrong thing and correct those as quickly as possible. And it is working. It is working.” Charles O. “Chuck” Prince III, CEO of Citigroup, 2003-20072 “People know I was concerned about the markets. Clearly, there were things wrong. But I don’t know of anyone who foresaw a perfect storm, and that’s what we’ve had here.” Robert Rubin, chairman of Citigroup’s executive committee, 1999- 20093 “I do not think we did enough as [regulators] with the authority we had to help contain the risks that ultimately emerged in [Citigroup].” Timothy Geithner, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2003-2009; Secretary of the Treasury, 2009-20134 * Professor of Law and Executive Director of the Center for Law, Economics & Finance, George Washington University Law School. I wish to thank GW Law School and Dean Greg Maggs for a summer research grant that supported my work on this Article. I am indebted to Eric Klein, a member of GW Law’s Class of 2015, and Germaine Leahy, Head of Reference in the Jacob Burns Law Library, for their superb research assistance. -

Naadac Wellness and Recovery in the Addiction

NAADAC WELLNESS AND RECOVERY IN THE ADDICTION PROFESSION 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM CENTRAL MAY 5, 2021 CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: CAPTIONACCESS [email protected] www.captionaccess.com >> HeLLo, everyone and weLcome to part 5 of 6 of the speciaLty onLine training series on weLLness and recovery. Today's topic is MindfuLness with CLients - Sitting with Discomfort presented by Cary Hopkins Eyles. I'm reaLLy excited to have you guys as part of this presentation. My name is Jessie O'Brien. I'm the training and content manager here at NAADAC the association for addiction professionaLs. And I wiLL be the organizer for today's Learning experience. This onLine training is produced by NAADAC, the association for addiction professionaLs. CLosed captioning is provided by CaptionAccess today. So pLease check your most recent confirmation emaiL for a key Link to use closed captioning. As many of you know, every NAADAC onLine speciaLty series has its own webpage that houses everything you need to know about that particuLar series. If you missed a part of the series and decide to pursue the certificate of achievement you can register for the training that you missed, ticket on demand at your own pace, make the payment and take the quiz. You must be registered for any NAADAC training in order to access the quiz and get the credit. If you want any more information on the weLLness and recovery series, you can find it right there at that page. So this training today is approved for 1.5 continuing education hours, and our website contains a fuLL List of the boards and organizations that approve us as continuing education providers. -

Beckett and Nothing with the Negative Spaces of Beckett’S Theatre

8 Beckett, Feldman, Salcedo . Neither Derval Tubridy Writing to Thomas MacGreevy in 1936, Beckett describes his novel Murphy in terms of negation and estrangement: I suddenly see that Murphy is break down [sic] between his ubi nihil vales ibi nihil velis (positive) & Malraux’s Il est diffi cile à celui qui vit hors du monde de ne pas rechercher les siens (negation).1 Positioning his writing between the seventeenth-century occasion- alist philosophy of Arnold Geulincx, and the twentieth-century existential writing of André Malraux, Beckett gives us two visions of nothing from which to proceed. The fi rst, from Geulincx’s Ethica (1675), argues that ‘where you are worth nothing, may you also wish for nothing’,2 proposing an approach to life that balances value and desire in an ethics of negation based on what Anthony Uhlmann aptly describes as the cogito nescio.3 The second, from Malraux’s novel La Condition humaine (1933), contends that ‘it is diffi cult for one who lives isolated from the everyday world not to seek others like himself’.4 This chapter situates its enquiry between these poles of nega- tion, exploring the interstices between both by way of neither. Drawing together prose, music and sculpture, I investigate the role of nothing through three works called neither and Neither: Beckett’s short text (1976), Morton Feldman’s opera (1977), and Doris Salcedo’s sculptural installation (2004).5 The Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s work explores the politics of absence, par- ticularly in works such as Unland: Irreversible Witness (1995–98), which acts as a sculptural witness to the disappeared victims of war. -

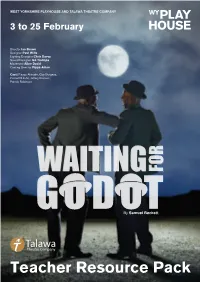

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

Rhythms in Rockaby: Ways of Approaching the Unknowable

83 Rhythms in Rockaby: Ways of Approaching the Unknowable. Leonard H. Knight Describing Samuel Beckett's later, and progressively shorter, pieces in a word is peculiarly difficult. The length of the average critical commentary on them testifies to this, and is due largely to an unravelling of compression in the interests of meaning: straightening out a tightly C9iled spring in order to see how it is made. The analogy, while no more exact than any analogy, is useful at least in suggesting two things: the difficulty of the endeavour; and the feeling, while engaged in it, that it may be largely counterproductive. A straightened out spring, after all, is no longer a spring. Aware of the pitfalls I should nevertheless like, in this paper, to look at part of the mechanism while trying to keep its overall shape relatively intact. The ideas in a Beckett play emerge, in general, from an initial image. A woman half-buried in a grass mound. A faintly spotlit, endlessly talking mouth. Feet tracing a fixed, unvarying path. Concrete and intensely theatrical, the image is immediately graspable. Its force and effectiveness come, above all, from its simpl icity. Described in this way Beckett's images sound arresting to the point of sen sationalism. What effectively lowers the temperature while keeping the excitement generated by their o.riginality is the simple fact that they cannot easily be made out. They are seen, certainly - but only just. In the dimmest possible light; the absolute minimum commensurate with sight. What is initially seen is only then augmented or reinforced by what is said. -

What Are They Doing There? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1989 What are they doing there? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gehman, William Geoffrey, "What are they doing there? :" (1989). Theses and Dissertations. 4957. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/4957 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • ,, WHAT ARE THEY DOING THERE?: ACTING AND ANALYZING SAMUEL BECKETT'S HAPPY DAYS by William Geoffrey Gehman A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University 1n Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts 1n English Lehigh University 1988 .. This thesis 1S accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. (date) I Professor 1n Charge Department Chairman 11 ACD01fLBDGBNKNTS ., Thanks to Elizabeth (Betsy) Fifer, who first suggested Alan Schneider's productions of Samuel Beckett's plays as a thesis topic; and to June and Paul Schlueter for their support and advice. Special thanks to all those interviewed, especially Martha Fehsenfeld, who more than anyone convinced the author of Winnie's lingering presence. 111 TABLB OF CONTBNTS Abstract ...................•.....••..........•.•••••.••.••• 1 ·, Introduction I Living with Beckett's Standards (A) An Overview of Interpreting Winnie Inside the Text ..... 3 (B) The Pros and Cons of Looking for Clues Outside the Script ................................................ 10 (C) The Play in Context .................................. -

'One Other Living Soul': Encountering Strangers in Samuel Beckett's Dramatic Works

Andrew Goodspeed (Macedonia) ‘one other living soul’: Encountering Strangers in Samuel Beckett’s Dramatic Works This essay seeks to explore an admittedly minor area of the study of Samuel Beck- ett’s drama – the encounter with strangers, and one’s relations with strangers. It is the rarity of such situations that makes it perhaps worth investigating, because these encoun- ters shed light on Beckett’s more general dramatic concerns. As is well acknowledged, Beckett’s theatrical work tends to focus on small groups in close and clear relations with one another, or indeed with individuals enduring memories or voices that will not let them rest (here one might nominate, as examples, Eh Joe or Embers). Setting aside those indi- viduals, the tight concentration of Beckett’s writing upon a few individuals in a specific relation to one another – as in perhaps Come and Go or Play—is one of the playwright’s most common dramatic elements, and likely represents an aspect of his famous efforts towards concentration and compression of dramatic experience. By studying the opposite of these instances, particularly when his characters encounter or remember encountering strangers, this paper hopes to gain some insight upon the more general trends of Beckett’s stagecraft and dramatic themes. It should be acknowledged at the outset, however, that there are a number of am- biguous situations in Beckett’s drama relating to the question of how closely individuals know or relate to one another. A simple survey of people who are obviously strangers or are clearly known to one another is not easily accomplished in Beckett’s drama.