Chapter 12 Clovis Across the Continent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio History Lesson 1

http://www.touring-ohio.com/ohio-history.html http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/category.php?c=PH http://www.oplin.org/famousohioans/indians/links.html Benchmark • Describe the cultural patterns that are visible in North America today as a result of exploration, colonization & conflict Grade Level Indicator • Describe, the earliest settlements in Ohio including those of prehistoric peoples The students will be able to recognize and describe characteristics of the earliest settlers Assessment Lesson 2 Choose 2 of the 6 prehistoric groups (Paleo-indians, Archaic, Adena, Hopewell, Fort Ancients, Whittlesey). Give two examples of how these groups were similar and two examples of how these groups were different. Provide evidence from the text to support your answer. Bering Strait Stone Age Shawnee Paleo-Indian People Catfish •Pre-Clovis Culture Cave Art •Clovis Culture •Plano Culture Paleo-Indian People • First to come to North America • “Paleo” means “Ancient” • Paleo-Indians • Hunted huge wild animals for food • Gathered seeds, nuts and roots. • Used bone needles to sew animal hides • Used flint to make tools and weapons • Left after the Ice Age-disappeared from Ohio Archaic People Archaic People • Early/Middle Archaic Period • Late Archaic Period • Glacial Kame/Red Ocher Cultures Archaic People • Archaic means very old (2nd Ohio group) • Stone tools to chop down trees • Canoes from dugout trees • Archaic Indians were hunters: deer, wild turkeys, bears, ducks and geese • Antlers to hunt • All parts of the animal were used • Nets to fish -

Visualizing Paleoindian and Archaic Mobility in the Ohio

VISUALIZING PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC MOBILITY IN THE OHIO REGION OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amanda N. Colucci May 2017 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation written by Amanda N. Colucci B.A., Western State Colorado University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Mark Seeman, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Eric Shook, Ph.D., Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. James Tyner, Ph.D. Dr. Richard Meindl, Ph.D. Dr. Alison Smith, Ph.D. Accepted by Dr. Scott Sheridan, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Geography Dr. James Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………………………………..……...……. III LIST OF FIGURES ….………………………………………......………………………………..…….…..………iv LIST OF TABLES ……………………………………………………………….……………..……………………x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..………………………….……………………………..…………….………..………xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 STUDY AREA AND TIMEFRAME ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.1 Paleoindian Period ............................................................................................................................... -

A North American Perspective on the Volg (PDF)

Quaternary International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint A North American perspective on the Volgu Biface Cache from Upper Paleolithic France and its relationship to the “Solutrean Hypothesis” for Clovis origins J. David Kilby Department of Anthropology, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The “Solutrean hypothesis” for the origins of the North American Clovis Culture posits that early North American Volgu colonizers were direct descendants of European populations that migrated across the North Atlantic during the Clovis European Upper Paleolithic. The evidential basis for this model rests largely on proposed technological and Solutrean behavioral similarities shared by the North American Clovis archaeological culture and the French and Iberian Cache Solutrean archaeological culture. The caching of stone tools by both cultures is one of the specific behavioral correlates put forth by proponents in support of the hypothesis. While more than two dozen Clovis caches have been identified, Volgu is the only Solutrean cache identified at this time. Volgu consists of at least 15 exquisitely manufactured bifacial stone tools interpreted as an artifact cache or ritual deposit, and the artifacts themselves have long been considered exemplary of the most refined Solutrean bifacial technology. This paper reports the results of applying methods developed for the comparative analysis of the relatively more abundant caches of Clovis materials in North America to this apparently singular Solutrean cache. In addition to providing a window into Solutrean technology and perhaps into Upper Paleolithic ritual behavior, this comparison of Clovis and Solutrean assemblages serves to test one of the tangible archaeological implications of the “Solutrean hypoth- esis” by evaluating the technological and behavioral equivalence of Solutrean and Clovis artifact caching. -

Discover Illinois Archaeology

Discover Illinois Archaeology ILLINOIS ASSOCIATION FOR ADVANCEMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY Discover Illinois Archaeology Illinois’ rich cultural heritage began more collaborative effort by 18 archaeologists from than 12,000 years ago with the arrival of the across the state, with a major contribution by ancestors of today’s Native Americans. We learn Design Editor Kelvin Sampson. Along with sum- about them through investigations of the remains maries of each cultural period and highlights of they left behind, which range from monumental regional archaeological research, we include a earthworks with large river-valley settlements to short list of internet and print resources. A more a fragment of an ancient stone tool. After the extensive reading list can be found at the Illinois arrival of European explorers in the late 1600s, a Association for Advancement of Archaeology succession of diverse settlers added to our cul- web site www.museum.state.il.us/iaaa/DIA.pdf. tural heritage, leading to our modern urban com- We hope that by reading this summary of munities and the landscape we see today. Ar- Illinois archaeology, visiting a nearby archaeo- chaeological studies allow us to reconstruct past logical site or museum exhibit, and participating environments and ways of life, study the rela- in Illinois Archaeology Awareness Month pro- tionship between people of various cultures, and grams each September, you will become actively investigate how and why cultures rise and fall. engaged in Illinois’ diverse past and DISCOVER DISCOVER ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGY, ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGY. summarizing Illinois culture history, is truly a Alice Berkson Michael D. Wiant IIILLINOIS AAASSOCIATION FOR CONTENTS AAADVANCEMENT OF INTRODUCTION. -

Olde New Mexico

Olde New Mexico Olde New Mexico By Robert D. Morritt Olde New Mexico, by Robert D. Morritt This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Robert D. Morritt All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2709-6, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2709-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................... vii Preface........................................................................................................ ix Sources ....................................................................................................... xi The Clovis Culture ...................................................................................... 1 Timeline of New Mexico History................................................................ 5 Pueblo People.............................................................................................. 7 Coronado ................................................................................................... 11 Early El Paso ............................................................................................ -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB .vo ion-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUH151990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca. 11,500-7500 BP B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Sub-context; Clovis Culture; 11,500-11,000 B.P.____________ sub-context: Folsom Culture; 11,000-10,000 B.P. Sub-context; Piano Culture: 10,000-7500 B.P. C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The Plains Region of Colorado is that area of the state within the Great Plains Physiographic Province, comprising most of the eastern half of the state (Figure 1). The Colorado Plains is bounded on the north, east and south by the Colorado State Line. On the west, it is bounded by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. [_]See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relaje«kproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional renuirifiaejits set forth in 36 CFSKPaV 60 and. -

Archaeology of Northwestern Oklahoma: an Overview

ARCHAEOLOGY OF NORTHWESTERN OKLAHOMA: AN OVERVIEW A Thesis by Mackenzie Diane Stout B.A., Wichita State University, 2005 Submitted to the Department of Anthropology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2010 ©Copyright 2010 by Mackenzie Stout All Rights Reserved ARCHAEOLOGY OF NORTHWESTERN OKLAHOMA: AN OVERVIEW The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Anthropology. _________________________________ David T. Hughes, Committee Chair _________________________________ Jay Price, Committee Member _________________________________ Peer Moore-Jansen, Committee Member DEDICATION To my father, my husband, my twin, and the rest of the family iii ABSTRACT This work will compile recent archaeological information about prehistoric inhabitants of northwest Oklahoma, the environments they occupied, and the archaeological studies that have informed us about them. The purpose is to construct an overview of the region that has been developed since the 1980s. Recommendations are offered about possible research objectives that might help tie this area in with larger studies of landscape archaeology, prehistoric adaptations to the area, and settlement systems. The primary contribution of the present study is to compile and make available in a single source some of the important information recently developed for Alfalfa, Blaine, Dewey, Ellis, Garfield, Grant, Harper, Kingfisher, Major, Woods, and Woodward counties. Studies in this area have added substantial information in the areas of pre-Clovis first Americans, the Clovis and other Paleoindian cultures, Archaic, and more recent inhabitants of the region. -

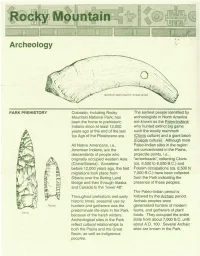

Rocky Mountain

Rocky Mountain Archeology PARK PREHISTORY Colorado, including Rocky The earliest people identified by Mountain National Park, has archeologists in North America been the home to prehistoric are known as the Paleo-lndians Indians since at least 12,000 who hunted extinct big game years ago at the end of the last such the woolly mammoth Ice Age of the Pleistocene era. (Clovis culture) and a giant bison (Folsom culture). Although most All Native Americans, i.e., Paleo-lndian sites in the region American Indians, are the are concentrated in the Plains, descendents of people who projectile points, i.e., originally occupied western Asia "arrowheads", reflecting Clovis (China/Siberia). Sometime (ca. 9,500 to 8,500 B.C.) and before 12,000 years ago, the first Folsom occupations (ca. 8,500 to migrations took place from 7,000 B.C.) have been collected Siberia over the Bering Land from the Park indicating the Bridge and then through Alaska presence of these peoples. and Canada to the "lower 48". The Paleo-lndian period is Throughout prehistoric and early followed by the Archaic period. historic times, seasonal use by Archaic peoples were Folsom hunters and gatherers was the generalized hunters of modern predominate life-style in the Park fauna, and gatherers of plant Clovis because of the harsh winters. foods. They occupied the entire Archeological sites in the Park state from about 7,000 B.C. until reflect cultural relationships to about A.D. 100. Several Archaic both the Plains and the Great sites are known in the Park. Basin, as well as indigenous peoples. -

Examination of the Owens Cache in Southeastern Colorado

EXAMINATION OF THE OWENS CACHE IN SOUTHEASTERN COLORADO by THADDEUS HARRISON SWAN B.A., Fort Lewis College, 1999 A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Geography and Environmental Studies 2019 © 2019 THADDEUS HARRISON SWAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This thesis for the Master of Arts degree by Thaddeus Harrison Swan has been approved for the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies by Brandon Vogt, Chair Thomas Huber Stance Hurst Date: May 8, 2019 ii Swan, Thaddeus Harrison (M.A., Applied Geography) Examination of the Owens Cache in Southeastern Colorado Thesis directed by Associate Professor Brandon Vogt ABSTRACT Throughout North America, caches are recognized as an important feature type in prehistoric research. Unlike other site or feature types, the materials associated with these assemblages are not a result of discard, breakage during manufacture, or accidental loss, but represent a rare window into prehistoric toolkits where usable items within various stages of manufacture are stored for future use. In addition, cache locations and the raw material source locations of the feature contents can assist with research questions regarding mobility and settlement/subsistence strategies (among others). However, many caches have been removed from their original context either through disturbance or discovery by non-archaeologists, who unwittingly destroy the context of the find. In other instances, archaeologists discover cache locations that are largely disturbed by erosion or lack the organic or temporal-cultural diagnostic artifact traits necessary for placement in a chronological framework, which greatly restricts the interpretive value of these assemblages. -

KIVA INDEX: Volumes 1 Through 83

1 KIVA INDEX: Volumes 1 through 83 This index combines five previously published Kiva indexes and adds index entries for the most recent completed volumes of Kiva. Nancy Bannister scanned the indexes for volumes 1 through 60 into computer files that were manipulated for this combined index. The first published Kiva index was prepared in 1966 by Elizabeth A.M. Gell and William J. Robinson. It included volumes 1 through 30. The second index includes volumes 31 through 40; it was prepared in 1975 by Wilma Kaemlein and Joyce Reinhart. The third, which covers volumes 41 through 50, was prepared in 1988 by Mike Jacobs and Rosemary Maddock. The fourth index, compiled by Patrick D. Lyons, Linda M. Gregonis, and Helen C. Hayes, was prepared in 1998 and covers volumes 51 through 60. I prepared the index that covers volumes 61 through 70. It was published in 2006 as part of Kiva volume 71, number 4. Brid Williams helped proofread the index for volumes 61 through 70. To keep current with our volume publication and the needs of researchers for on-line information, the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society board decided that it would be desirable to add entries for each new volume as they were finished. I have added entries for volumes 71 through 83 to the combined index. It is the Society's goal to continue to revise this index on a yearly basis. As might be expected, the styles of the previously published indexes varied, as did the types of entries found. I changed some entries to reflect current terminology. -

Article Info Abstract

Journal of Archaeological Science 53 (2015) 550e558 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Neutron activation analysis of 12,900-year-old stone artifacts confirms 450e510þ km Clovis tool-stone acquisition at Paleo Crossing (33ME274), northeast Ohio, U.S.A. * Matthew T. Boulanger a, b, , Briggs Buchanan c, Michael J. O'Brien b, Brian G. Redmond d, * Michael D. Glascock a, Metin I. Eren b, d, a Archaeometry Laboratory, University of Missouri Research Reactor, Columbia, MO, 65211, USA b Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, 65211, USA c Department of Anthropology, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, 74104, USA d Department of Archaeology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH, 44106-1767, USA article info abstract Article history: The archaeologically sudden appearance of Clovis artifacts (13,500e12,500 calibrated years ago) across Received 30 August 2014 Pleistocene North America documents one of the broadest and most rapid expansions of any culture Received in revised form known from prehistory. One long-asserted hallmark of the Clovis culture and its rapid expansion is the 1 November 2014 long-distance acquisition of “exotic” stone used for tool manufacture, given that this behavior would be Accepted 5 November 2014 consistent with geographically widespread social contact and territorial permeability among mobile Available online 13 November 2014 hunteregatherer populations. Here we present geochemical evidence acquired from neutron activation analysis (NAA) of stone flaking debris from the Paleo Crossing site, a 12,900-year-old Clovis camp in Keywords: Clovis northeastern Ohio. These data indicate that the majority stone raw material at Paleo Crossing originates Colonization from the Wyandotte chert source area in Harrison County, Indiana, a straight-line distance of 450 Long-distance resource acquisition e510 km. -

Clovis and Folsom Functionality Comparison by Andrew J. Richard

Clovis and Folsom Functionality Comparison Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Richard, Andrew Justin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 07:50:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/556853 Clovis and Folsom Functionality Comparison by Andrew J. Richard ____________________________ Copyright © Andrew J. Richard 2015 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2015 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Andrew J. Richard APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: _____ ____27 April 2015____ Vance T. Holliday Date Professor of Anthropology and Geosciences 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The idea to use ceramic as a medium was made based on conversations with Jesse Ballenger Ph.D., Kacy Hollenback Ph.D., Michael Schiffer Ph.D., C.