Olde New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwestern Monuments

SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS MONTHLY REPORT MAY 1939 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE GPO W055 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR *$*&*">&•• NATIONAL PARK SERVICE / •. •: . • • r. '• WASHINGTON ADDRESS ONLY THE DIRECTOR. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE April 2k. 1939. Memorandum for the Superintendent, Southwestern National Monuments: I am writing this as an open letter to you because all of us recognize the fine friendly spirit engendered by your Southwestern National Monuments n.onthly reports. I believe that all park and monument reports can be made as interesting and informative as yours. Your monthly report for L.erch i6 on my desk and I have glanced through its pages, checking your opening statements, stopping here and there to j.ick up en interesting sidelight, giving a few moments to the supplement, and then looking to your "Ruminations". The month isn't complete unless I read themJ As you know, the submission of the monthly reports from the field has been handled as another required routine statement by some of the field men. It seems to me you have strained every effort to rrake the reports from the Southwestern National Monuments an outstanding re flection of current events, history, and special topics; adding a good share of the personal problems and living conditions of that fine group of men and women that constitute your field organization. You have ac complished a great deal by making the report so interesting that the Custodians look forward to the opportunity of adding their notes. In issuing these new instructions, I am again requesting that the Superintendents and Custodians themselves take the time to put in writing the story of events, conditions, and administration in the parks and monuments they represent. -

Ohio History Lesson 1

http://www.touring-ohio.com/ohio-history.html http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/category.php?c=PH http://www.oplin.org/famousohioans/indians/links.html Benchmark • Describe the cultural patterns that are visible in North America today as a result of exploration, colonization & conflict Grade Level Indicator • Describe, the earliest settlements in Ohio including those of prehistoric peoples The students will be able to recognize and describe characteristics of the earliest settlers Assessment Lesson 2 Choose 2 of the 6 prehistoric groups (Paleo-indians, Archaic, Adena, Hopewell, Fort Ancients, Whittlesey). Give two examples of how these groups were similar and two examples of how these groups were different. Provide evidence from the text to support your answer. Bering Strait Stone Age Shawnee Paleo-Indian People Catfish •Pre-Clovis Culture Cave Art •Clovis Culture •Plano Culture Paleo-Indian People • First to come to North America • “Paleo” means “Ancient” • Paleo-Indians • Hunted huge wild animals for food • Gathered seeds, nuts and roots. • Used bone needles to sew animal hides • Used flint to make tools and weapons • Left after the Ice Age-disappeared from Ohio Archaic People Archaic People • Early/Middle Archaic Period • Late Archaic Period • Glacial Kame/Red Ocher Cultures Archaic People • Archaic means very old (2nd Ohio group) • Stone tools to chop down trees • Canoes from dugout trees • Archaic Indians were hunters: deer, wild turkeys, bears, ducks and geese • Antlers to hunt • All parts of the animal were used • Nets to fish -

Visualizing Paleoindian and Archaic Mobility in the Ohio

VISUALIZING PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC MOBILITY IN THE OHIO REGION OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amanda N. Colucci May 2017 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation written by Amanda N. Colucci B.A., Western State Colorado University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Mark Seeman, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Eric Shook, Ph.D., Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. James Tyner, Ph.D. Dr. Richard Meindl, Ph.D. Dr. Alison Smith, Ph.D. Accepted by Dr. Scott Sheridan, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Geography Dr. James Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………………………………..……...……. III LIST OF FIGURES ….………………………………………......………………………………..…….…..………iv LIST OF TABLES ……………………………………………………………….……………..……………………x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..………………………….……………………………..…………….………..………xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 STUDY AREA AND TIMEFRAME ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.1 Paleoindian Period ............................................................................................................................... -

Native Peoples of North America

Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins SUNY Potsdam Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins 2013 Open SUNY Textbooks 2013 Susan Stebbins This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library (IITG PI) State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 Cover design by William Jones About this Textbook Native Peoples of North America is intended to be an introductory text about the Native peoples of North America (primarily the United States and Canada) presented from an anthropological perspective. As such, the text is organized around anthropological concepts such as language, kinship, marriage and family life, political and economic organization, food getting, spiritual and religious practices, and the arts. Prehistoric, historic and contemporary information is presented. Each chapter begins with an example from the oral tradition that reflects the theme of the chapter. The text includes suggested readings, videos and classroom activities. About the Author Susan Stebbins, D.A., Professor of Anthropology and Director of Global Studies, SUNY Potsdam Dr. Susan Stebbins (Doctor of Arts in Humanities from the University at Albany) has been a member of the SUNY Potsdam Anthropology department since 1992. At Potsdam she has taught Cultural Anthropology, Introduction to Anthropology, Theory of Anthropology, Religion, Magic and Witchcraft, and many classes focusing on Native Americans, including The Native Americans, Indian Images and Women in Native America. Her research has been both historical (Traditional Roles of Iroquois Women) and contemporary, including research about a political protest at the bridge connecting New York, the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation and Ontario, Canada, and Native American Education, particularly that concerning the Native peoples of New York. -

Lower Arkansas River – Derby to Ark City

LOWER ARKANSAS BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody/Assessment Unit (AU): Lower Arkansas River – Derby to Ark City Water Quality Impairment: Chloride 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Ark River (Derby), Ark River (Oxford), Ark River (Ark City), South Fork Ninnescah River, Ninnescah River, Slate Creek, Unmonitored Basin County: Cowley, Sumner, Sedgwick, Kingman, Pratt, Kiowa HUC 8: 11030013, 11030015, 11030016, 11060001 HUC 11 (HUC 14s): 11030013020(050) 11030013030(010, 030, 040, 050, 060, 070, 080, 090) 11030015010(010, 020, 030, 040, 050, 060, 070, 080, 090) 11030015030(010, 020, 030, 040, 050, 060) 11030016010(010, 020, 030, 040, 050) 11030016020(010, 020, 030) 11060001040(010) Ecoregion: Central Great Plains, Wellington-McPherson Lowland (27d) Flint Hills (28) Drainage Area: 1,653 square miles Main Stem Segments: 11030013 (AU Station 528): Slate Cr (17) (AU Station 281): Arkansas R (3-part) (AU Station 527): Arkansas R (2-part, 3-part, 18) (AU Station 218): Arkansas R (1, 2-part) 11030015 (AU Station 036): S.F. Ninnescah R (1,3,4,6) 11030016 (AU Station 280): Ninnescah R (1,3,8) 11060001 (AU Station 218): Arkansas R (14, 18) 1 Main Stem Segments with Tributaries by HUC 8 and Watershed/Station Number: Table 1 (a-f) a. HUC8 11030013 Watershed Slate Creek Station 528 Slate Cr (17) (partial) Winser Cr (32) Antelope Cr (25) Beaver Cr (29)* Hargis Cr (24)* Oak Cr (26)* Spring Cr (27)* * Not impaired b. HUC8 11030013 Watershed Arkansas River (Derby) Station 281 Arkansas R (3 - part) Spring Cr (37) c. HUC8 11030013 Watershed Arkansas River (Oxford) Station 527 Arkansas R (2 -part) Spring Cr (34) Lost Cr (23) Arkansas R (18) Arkansas R (3 - part) Bitter Cr (28) Dog Cr (531) d. -

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project Research Topics Written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. John Howard White

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project Research Topics Written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. John Howard White, Ph.D. Edited by Angélica Sánchez-Clark, Ph.D. With the assistance of Hector Contreras, David Gómez and Feliza Monta University of New Mexico Graduate Students Spanish Colonial Research Center A Partnership between the University of New Mexico and the National Park Service [Version Date: May 20, 2014] 1 Coronado National Memorial Coronado Expedition Research Topics 1) Research the lasting effects of the expedition in regard to exchanges of cultures, Native American and Spanish. Was the shaping of the American Southwest a direct result of the Coronado Expedition's meetings with natives? The answer to this question is embedded throughout the other topics. However, by 1575, the Spanish Crown declared that the conquest was over and the new policy of pacification would be in force. Still, the next phase that would shape the American Southwest involved settlement, missionization, and expansion for valuable resources such as iron, tin, copper, tar, salt, lumber, etc. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s expedition did set the Native American wariness toward the Spanish occupation of areas close to them. Rebellions were the corrective to their displeasure over colonial injustices and institutions as well as the mission system that threatened their beliefs and spiritualism. In the end, a kind of syncretism and symbiosis resulted. Today, given that the Spanish colonial system recognized that the Pueblos and mission Indians had a legal status, land grants issued during that period protects their lands against the new settlement pattern that followed: that of the Anglo-American. -

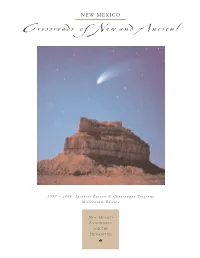

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Register Listed National Park Service 1-20-2012 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Winfield National Bank Building other names/site number KHRI #035-5970-00010 2. Location street & number 901 Main Street not for publication city or town Winfield vicinity state Kansas code KS county Cowley code 035 zip code 67156 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide x local SEE FILE ____________________________________ Signature of certifying official Date _____________________________________ Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

People, Place and the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Visions of the landscape| People, place and the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River Jerritt J. Frank The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Frank, Jerritt J., "Visions of the landscape| People, place and the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4023. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4023 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of IVIONXAiVA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that tliis material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission ^ No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature _/ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only wit the author's explicit consent. Visions of the Landscape: People, Place and the Black Canyon Of The Gunnison River by Jerritt J. Frank B.A. Mesa State College, 1999 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana May 2003 >4jB^oved by: ^lairperson Dean, Graduate School 5-q-03 Date UMI Number: EP36289 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

Plains Anthropologist Author Index

Author Index AUTHOR INDEX Aaberg, Stephen A. (see Shelley, Phillip H. and George A. Agogino) 1983 Plant Gathering as a Settlement Determinant at the Pilgrim Stone Circle Site. In: Memoir 19. Vol. 28, No. (see Smith, Calvin, John Runyon, and George A. Agogino) 102, pp. 279-303. (see Smith, Shirley and George A. Agogino) Abbott, James T. Agogino, George A. and Al Parrish 1988 A Re-Evaluation of Boulderflow as a Relative Dating 1971 The Fowler-Parrish Site: A Folsom Campsite in Eastern Technique for Surficial Boulder Features. Vol. 33, No. Colorado. Vol. 16, No. 52, pp. 111-114. 119, pp. 113-118. Agogino, George A. and Eugene Galloway Abbott, Jane P. 1963 Osteology of the Four Bear Burials. Vol. 8, No. 19, pp. (see Martin, James E., Robert A. Alex, Lynn M. Alex, Jane P. 57-60. Abbott, Rachel C. Benton, and Louise F. Miller) 1965 The Sister’s Hill Site: A Hell Gap Site in North-Central Adams, Gary Wyoming. Vol. 10, No. 29, pp. 190-195. 1983 Tipi Rings at York Factory: An Archaeological- Ethnographic Interface. In: Memoir 19. Vol. 28, No. Agogino, George A. and Sally K. Sachs 102, pp. 7-15. 1960 Criticism of the Museum Orientation of Existing Antiquity Laws. Vol. 5, No. 9, pp. 31-35. Adovasio, James M. (see Frison, George C., James M. Adovasio, and Ronald C. Agogino, George A. and William Sweetland Carlisle) 1985 The Stolle Mammoth: A Possible Clovis Kill-Site. Vol. 30, No. 107, pp. 73-76. Adovasio, James M., R. L. Andrews, and C. S. Fowler 1982 Some Observations on the Putative Fremont Agogino, George A., David K.