A Brief History of Whiskey Adulteration and the Role of Spectroscopy Combined with Chemometrics in the Detection of Modern Whiskey Fraud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lactic Acid Bacteria – the Uninvited but Generally Welcome Participants In

Lactic acid bacteria – the uninvited (a) but generally welcome participants in malt whisky fermentation Fergus G. Priest Coffey still. Like malt diversity resulting in Lactobacillus fermentum and LEFT: (b) whisky, it must be matured Lactobacillus paracasei as commonly dominant species by Fig. 1. Fluorescence photomicrographs of whisky for a minimum of 3 years. about 40 hours. During the final stages when the yeast is fermentation samples; green cells Grain whisky is the base of dying, a homofermentative bacterium related to Lacto- are viable, red cells are dead. (a) the standard blends such as bacillus acidophilus often proliferates and produces large Wort on entering the washback, (b) Famous Grouse, Teachers, amounts of lactic acid. after fermentation for 55 hours and and Johnnie Walker which (c) after fermentation for 95 hours. (a) AND (b) ARE REPRODUCED will contain between 15 Effects of lactobacilli on the flavour of malt WITH PERMISSION FROM VAN BEEK & and 30 % malt whisky. whisky PRIEST (2002, APPL ENVIRON Both products use a The bacteria can affect the flavour of the spirit in two MICROBIOL 68, 297–305); (c) COURTESY F. G. PRIEST similar process, but here ways. First, they will reduce the pH of the fermentation we will focus on malt (c) through the production of acetic and lactic acids. This whisky. Malted barley is will lead to a general increase in esters following milled, infused in water at distillation, a positive feature that has traditionally been about 64 °C for some 30 associated with the late lactic fermentation. This general minutes to 1 hour and the effect is apparent in the data presented in Fig. -

Alcohol Units a Brief Guide

Alcohol Units A brief guide 1 2 Alcohol Units – A brief guide Units of alcohol explained As typical glass sizes have grown and For example, most whisky has an ABV of 40%. popular drinks have increased in A 1 litre (1,000ml) bottle of this whisky therefore strength over the years, the old rule contains 400ml of pure alcohol. This is 40 units (as 10ml of pure alcohol = one unit). So, in of thumb that a glass of wine was 100ml of the whisky, there would be 4 units. about 1 unit has become out of date. And hence, a 25ml single measure of whisky Nowadays, a large glass of wine might would contain 1 unit. well contain 3 units or more – about the The maths is straightforward. To calculate units, same amount as a treble vodka. take the quantity in millilitres, multiply it by the ABV (expressed as a percentage) and divide So how do you know how much is in by 1,000. your drink? In the example of a glass of whisky (above) the A UK unit is 10 millilitres (8 grams) of pure calculation would be: alcohol. It’s actually the amount of alcohol that 25ml x 40% = 1 unit. an average healthy adult body can break down 1,000 in about an hour. So, if you drink 10ml of pure alcohol, 60 minutes later there should be virtually Or, for a 250ml glass of wine with ABV 12%, none left in your bloodstream. You could still be the number of units is: suffering some of the effects the alcohol has had 250ml x 12% = 3 units. -

Know Your Liquor VODKA WHISKY

Know Your Liquor VODKA Good to know: Vodka is least likely to give you a hangover Vodka is made by fermenting grains or crops such as potatoes with yeast. It's then purified and repeatedly filtered, often through charcoal, strange as it sounds, until it's as clear as possible. CALORIES: Because vodka contains no carbohydrates or sugars, it contains only calories from ethanol (around 7 calories per gram), making it the least-fattening alcoholic beverage. So a 35ml shot of vodka would contain about 72 calories. PROS: Vodka is the 'cleanest' alcoholic beverage because it contains hardly any 'congeners' - impurities normally formed during fermentation.These play a big part in how bad your hangover is. Despite its high alcohol content - around 40 per cent - vodka is the least likely alcoholic drink to leave you with a hangover, said a study by the British Medical Association CONS: Vodka is often a factor in binge drinking deaths because it is relatively tasteless when mixed with fruit juices or other drinks. HANGOVER SEVERITY: 3/10 WHISKY Good to know: Whisky or Scotch is distilled from fermented grains, such as barley or wheat, then aged in wooded casks. Whisky 'madness': It triggers erratic and unpredictable behaviour because most people drink whisky neat CALORIES: About 80 calories per 35ml shot. PROS: Single malt whiskies have been found to contain high levels of ellagic acid, according to Dr Jim Swan of the Royal Society of Chemists. This powerful acid inhibits the growth of tumours caused by certain carcinogens and kills cancer cells without damaging healthy cells. -

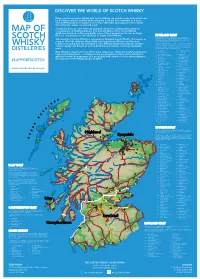

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Premium Scotch Whisky Beer Martinis Contemporary

MARTINIS THE RUDE COSMOPOLITAN | Patron Silver, Triple Sec, Cranberry and Lime Juices LEMON BASIL | Fresh Basil, Absolut Citron, Lemon Juice STRAWBERRY BASIL | Tito’s Vodka, Tanqueray Gin, Fresh Basil, Fresh Lime Juice, Strawberry Puree JOHNNY’S ITALIAN MANHATTAN | Templeton Rye, Campari, Sweet Vermouth MANGO VOLARE | Tito’s Vodka, Simple Syrup, Mango Puree RASPBERRY LIMONCELLO | Ketel One Vodka, Limoncello, Raspberry Puree INNAMORATA APPLE DROP | Dekuyper Apple Pucker, Dekuyper Buttershots TEMPLETON SMASH | Black Berries, Honey, Mint Leaves, Templeton Rye, Lemon Juice PINEAPPLE COCONUT | Malibu Coconut Rum, Pineapple Juice, Grenadine TUSCAN SUNRISE | Malibu Rum, Titos Vodka, Pineapple Juice, Orange Juice RUMCHATINI | Rumchatta, Vanilla Vodka, Frangelico and ground cinnamon THE DIRTY BIRD | Grey Goose Vodka, Bombay Sapphire, Olive Juice and Blue Cheese Stuffed Olives PREMIUM SCOTCH WHISKY THE GLENLIVET Single Malt, Aged 12 years JOHNNIE WALKER BLACK LABEL Blended Scotch Whiskey, Aged 12 years PLATINUM LABEL Blended Scotch Whiskey, Aged 18 years BLUE LABEL Blended Scotch Whiskey THE BALVENIE Single Malt “Doublewood”, Aged 12 years THE BALVENIE Single Malt “Portwood”, Aged 21 years GLENMORANGIE Single Highland Malt, Aged 10 years THE MACALLAN Single Highland Malt, Aged 12 years DALWHINNIE Single Highland Malt, Aged 15 years THE MACALLAN Single Highland Malt, Aged 18 years CONTEMPORARY COCKTAILS LUXURY MARGARITA | Patron Silver Tequila, Agave Nectar, Lime Juice, on the rocks with a lime twist MOSCOW MULE | Smirnoff Vodka, Ginger Beer, and -

Japanese Whisky Wine Saké Flights Cocktails Beer

BEER COCKTAILS Ask your server for today’s rotating STRONG AND STIRRED SHAKEN AND CITRUS DEPARTURES beer selections BAMBOO MARTINI SERVICE 14 BETTY THE ROCKETSHIP 12 VANGUARD 10 Aria gin and Blinking Owl vodka, Pueblo Viejo tequila, lime leaf, Cruzan Blackstrap rum, rice milk, black americano, saké, toasted sesame, strawberry, citrus cordial sesame LAFCADIO 13 JOIN YOUR LOCAL 10 CATS WITHOUT ATTITUDE 9 Iwai whisky, cherry, ome, absinthe, bitters GOVERNMENT citrus vodka, pea shoot, honey St. George vodka, yuzu, apricot, miso THE CONFUSER 11 ZERO PROOF shochu, mezcal, aperol, vermouth CINEMA OF THE DAMNED 11 AVENUE OF THE FUNKIEST 8 Plantation 3 Star rum, coconut, soy, citrus cordial, passionfruit, BAMBOO OLD FASHIONED 12 lemon, grapefruit, shiso cinnamon · JAPANESE - Toki whisky, bitters · OAXACAN - Peloton mezcal, tequila blanco, mole bitters JAZZBAR NONAME 13 HOUSE HUSBAND 7 · TAMARIND - Ezra Brooks rye, tamarind honey, bitters Roku gin, ginger, nigori, mint, matcha green tea, plum soda WINE - Certified B Corporation JAPANESE WHISKY WE’RE PROUD TO FEATURE NATURAL, GRUET 10 | 45 AKASHI 14 ORGANIC, AND BIODYNAMIC WINES. Brut, New Mexico Blend 23 MINUS TIDE 12 | 54 A TO Z 12 | 54 HIBIKI HARMONY SPARKLING Blend ROSÉ Rosé, Mendocino County Brut Rosé, Newberg, OR IWAI 12 ROSE & SON 14 | 63 GRAMERCY CELLARS 13 | 58 Blend Sauvignon Blanc, Santa Barbara County RED Syrah, Columbia Valley, WA NIKKA COFFEY GRAIN 18 WHITE LO-FI 16 | 72 LA CLARINE FARM 14 | 63 Grain Chardonnay, Santa Barbara County Mourvédre, Sierra Foothills SUNTORY TOKI 11 Blend EYRIE 13 | 58 POCO A POCO 14 | 63 Pinot Gris, Dundee Hills, OR Pinot Noir, Russian River Valley TAKETSURU 17 Pure Malt DAY WINES ‘VIN DE DAYS’ 11 | 50 CLOS TIBURON 15 | 68 YAMAZAKI 18 YR. -

Exclusive, Rare, & Limited Release American Whiskey

EXCLUSIVE, RARE, & LIMITED RELEASE JEFFERSON’S EFFERSON S ESERVE LD UM ASK INISH BLOOD OATH BOURBON, PACT NO. 4 J ’ R O R C F ESSE AMES MERICAN UTLAW BRUICHLADDICH BLACK ART 5.1 J J A O IM EAM ELMER T. LEE SINGLE BARREL 2018 J B NOB REEK OURBON GEORGE T. STAGG KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON 2018 K C B AKER S ARK GLENFIDDICH WINTER STORM 21 YEAR M ’ M LD ORESTER TATESMAN OURBON MICHTER’S 10 YEAR KENTUCKY STRAIGHT RYE 2018 O F S B MOKY UARTZ OURBON OCTOMORE 8.3 S Q V5 B MUGGLERS OTCH TRAIGHT OURBON OCTOMORE 9.1 S ’ N S B IGGLY RIDGE MALL ARREL OURBON OLD FORESTER BIRTHDAY BOURBON 2018 W B S B B OODFORD ESERVE OURBON OLD RIP VAN WINKLE 10 YEAR BOURBON - 2018 W R B OODFORD ESERVE ASTER S OLLECTION HERRY OOD W.L. WELLER C.Y.P.B. – 2018 W R M ’ C C W MOKED ARLEY WILLIAM LARUE WELLER KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON-2018 S B YELLOWSTONE SELECT BOURBON AMERICAN WHISKEY TENNESSEE BEAT 3 RESERVE WHISKEY JACK DANIEL’S OLD NO. 7 MICHTER’S AMERICAN WHISKEY JACK DANIEL’S GENTLEMAN JACK SEGRAMS 7 CROWN SMUGGLERS’ NOTCH LITIGATION WHEAT WHISKEY STRANAHAN’S COLORADO WHISKEY RYE WESTLAND SHERRY WOOD AMERICAN SINGLE MALT ANGEL’S ENVY RYE BASIL HAYDEN’S RYE WHITE WHISKEY BULLEIT RYE MONADNOCK MOONSHINE FLAG HILL STRAIGHT RYE SMOKY QUARTZ GRANITE LIGHTNING HIGH WEST RENDEZVOUS RYE HUDSON MANHATTAN RYE BOURBON JACK DANIELS SINGLE BARREL RYE JAMES E. PEPPER 1776 STRAIGHT RYE 1792 SMALL BATCH BOURBON LOCK STOCK & BARREL STRAIGHT RYE WHISKY AMADOR WHISKEY CO. -

Colleges Can Subscribe to the B.M.7

540 30 August 1969 News and Notes WHITTET, Craig Dunain Hospital, Inverness, epi- of the Brompton Hospital), Fulham Road, SOCIETY OF APOTHECARIES OF demioldgy of alcoholism in the Highlands and Islands, £7,500 over three years, from funds pro- London S.W.3, on Fridays at 5 p.m. from LONDON vided by the Distillers Company Limited for 3 October to 5 December inclusive. L.M.S.S.A.-S. G. Taktak, A. M. Hasan, H. T. research into alcoholism. Abu-Zahra, K. G. A. M. Ghattas, L. S. Nakhla, Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.3.5669.540 on 30 August 1969. Downloaded from B. A. K. Al-Kazzaz, M. Amanullah, F. R. Akrawy, IX Congris National des Midecins de M. A. Shanif, W M. Umrani, A. F. M. S. Rahman, Strike by Ambulance Men M. M. Abdel Rahman, W. F. Abadir, J. Y. Hallac, Ambulance drivers withdrew services from Centres de Sante.-16-18 October. Details A. F M. Shamsul Alam, M. Impallomeni, D. B. from Secretariat, 3 rue de Stockholm, Albuquerque, 0. E. F. M. Fadl, M. Habboushe, 25 of London's 76 ambulance stations earlier G. Gordon, G. R. Tadross, F. S. Mina, M. A. B, this week, and the Federation of Ambulance Paris 8. El-Gothamy, A. A. Shihata, S. D. Sarkar, A. M. H Aboul-Ata, E. F. Sayegh, J. K. S. Wee, S. S. Personnel claimed that the strike action Michail, M. H. Rahman, A. R. I. Ahmed, Z. would be extended if its claims were not met. Symposium on Patient Monitoring.-24 Husain. -

Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages Report of the Panel

WORLD TRADE WT/DS75/R WT/DS84/R ORGANIZATION 17 September 1998 (98-3471) Original: English Korea - Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages Report of the Panel The report of the Panel on Korea – Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages is being circulated to all Members, pursuant to the DSU. The report is being circulated as an unrestricted document from 17 September 1998 pursuant to the Procedures for the Circulation and Derestriction of WTO Documents (WT/L/160/Rev.1). Members are reminded that in accordance with the DSU only parties to the dispute may appeal a panel report. An appeal shall be limited to issues of law covered in the Panel report and legal interpretations developed by the Panel. There shall be no ex parte communications with the Panel or Appellate Body concerning matters under consideration by the Panel or Appellate Body. Note by the Secretariat: This Panel Report shall be adopted by the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) within 60 days after the date of its circulation unless a party to the dispute decides to appeal or the DSB decides by consensus not to adopt the report. If the Panel Report is appealed to the Appellate Body, it shall not be considered for adoption by the DSB until after the completion of the appeal. Information on the current status of the Panel Report is available from the WTO Secretariat. WT/DS75/R WT/DS84/R Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND........................................................................................................1 II. MEASURES IN ISSUE..........................................................................................................................3 -

The Banksoniain #10 an Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine August 2006

The Banksoniain #10 An Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine August 2006 Editorial Banks’s Next Books Apologies for the lateness of this issue, The next Banks book has been put back to unfortunately real life got in the way of March 2007. It also seems to have undergone writing and it basically missed its slot in my a name change and is now called The Steep quarterly schedule. If you want issues to Approach to Garbadale, rather than Matter come out on a more regular basis then please (which could have been a dull Physics contribute articles, or even just ideas for textbook). It also seems to have had another articles, or anything really. Contact details at working title, Empire (a History textbook?) the end of the last page. Please expect publication to be biannual from now on so The book after next, an Iain M. Banks effort look for issue #11 in February 2007. that is definitely Culture - the opening section of this book having been written before Steep The issue features The Crow Road, the book, Approach was started - has also been put back the TV series, the radio reading and the audio as a consequence of its predecessor‟s delay. book, and to help you make all the Iain is taking the summer off, and probably connections we have produced a family tree the winter as well, and plans to start work on of the major characters. This is probably my the Untitled Culture Novel in 2007 with favourite Banks book, and I found it difficult publication currently scheduled for August to write about possibly for that reason, but 2008. -

Scottish Industrial History Vol 20 2000

SCOTTISH INDUSTRIAL HISTORY Scotl21nd Business Archives Council of Scotland Scottish Charity Number SCO 02565 Volume20 The Business Archives Council of Scotland is grateful for the generous support given to this edition of Scottish Industrial History by United Distillers & Vintners SCOTTISH INDUSTRIAL HISTORY Volume20 B·A·C Scotl21nel Business Archives Council of Scotland Scorrish Choriry Number SCO 02565 Scottish Industrial History is published by the Business Archives Council of Scotland and covers all aspects of Scotland's industrial and commercial past on a local, regional and trans-national basis. Articles for future publication should be submitted to Simon Bennett, Honorary Editor, Scottish Industrial History, Archives & Business Records Centre, 77-87 Dumbarton Road, University of Glasgow Gll 6PE. Authors should apply for notes for contributors in the first instance. Back issues of Scottish Industrial History can be purchased and a list of titles of published articles can be obtained from the Honorary Editor or BACS web-site. Web-site: http://www.archives.gla.ac.uklbacs/default.html The views expressed in the journal are not necessarily those of the Business Archives Council of Scotland or those of the Honorary Editor. © 2000 Business Archives Council of Scotland and contributors. Cover illustrations Front: Advertisement Punch 1925- Johnnie Walker whisky [UDV archive] Back: Still room, Dalwhinnie Distillery 1904 [UDV archive] Printed by Universities Design & Print, University of Strathclyde 'Whisky Galore ' An Investigation of Our National Drink This edition is dedicated to the late Joan Auld, Archivist of the University of Dundee Scottish Industrial History Volume20 CONTENTS Page Scotch on the Records 8 Dr. R.B. -

SWR Guidance for Bottlers and Producers

The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 (SWR) came into force on 23 November 2009. They replaced the Scotch Whisky Act 1988 and the Scotch Whisky Order 1990. Whereas the previous legislation had only governed the way in which Scotch Whisky must be produced, the SWR also set out rules on how Scotch Whiskies must be labelled, packaged and advertised, as well as requiring Single Malt Scotch Whisky to be bottled in Scotland from 2012. The following guidance is aimed at assisting those producing and selling Scotch Whisky, and those designing labels, packaging and advertising, to comply with new law. Checklists are included where appropriate. This guidance covers only the main provisions of the law; the Regulations should be referred to for the full detail. The SWA’s Legal team is ready to assist with any questions. Contact details are provided at the end of this Guidance. Contents 1. Production of Scotch Whisky 3 2. Definitions of categories of Scotch Whisky 4 3. The only type of whisky may be produced in Scotland is Scotch Whisky 5 4. Passing Off 6 5. Export of Scotch Whisky in bulk 6 6. Labelling of Scotch Whisky 7 7. Distillery Names 8 8. Locality and regional geographical indications 9 9. Prohibition of the description “Pure Malt” 11 10. Maturation, age and distillation statements 11 11. Transitional periods regarding labelling, packaging and advertising 12 12. Verification of the authenticity of Scotch Whisky 12 13. Enforcement 13 Contact SWA Legal Team 13 2 The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 1.1 The SWR do not change the way that Scotch Whisky is produced.