Ocular Syphilis Anthony J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocular Leishmaniasis Presenting As Chronic

perim Ex en l & ta a l ic O p in l h t C h f Journal of Clinical & Experimental a o l m l a o n l r o g u Ayele et al., J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015, 6:1 y o J Ophthalmology ISSN: 2155-9570 DOI: 10.4172/2155-9570.1000395 Case Report Open Access Ocular Leishmaniasis Presenting as Chronic Ulcerative Blepharoconjunctivitis: A Case Report Fisseha Admassu Ayele*, Yared Assefa Wolde, Tesfalem Hagos and Ermias Diro University of Gondar, Gondar, Amhara, Ethiopia *Corresponding author: Fisseha Admassu Ayele MD, University of Gondar, Gondar, Amhara 196, Ethiopia, Tel: 251911197786; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: Dec 01, 2014, Accepted date: Feb 02, 2015, Published date: Feb 05, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Ayele FH, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Leishmaniasis is caused by unicellular eukaryotic obligate intracellular protozoa of the genus Leishmania that is endemic in over 98 countries in the world-most of which are developing countries including Ethiopia. It is transmitted by phlebotomine sandflies. The eye may be affected in cutaneous, mucocutaneous and Post Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis. We report a case of ocular leishmaniasis with eyelid and conjunctival involvement that had simulated ulcerative blepharoconjunctivitis not responding to conventional antibiotics. The patient was diagnosed by microscopy of a sample obtained via direct smear from the lesions. He was treated with systemic sodium stibogluconate (20 mg/kg/day) for 45 days and was clinically cured with this treatment. -

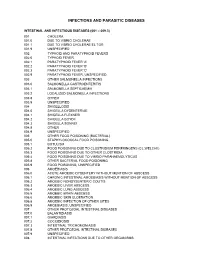

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

2012 Case Definitions Infectious Disease

Arizona Department of Health Services Case Definitions for Reportable Communicable Morbidities 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Definition of Terms Used in Case Classification .......................................................................................................... 6 Definition of Bi-national Case ............................................................................................................................................. 7 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ............................................... 7 AMEBIASIS ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ANTHRAX (β) ......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 ASEPTIC MENINGITIS (viral) ......................................................................................................................................... 11 BASIDIOBOLOMYCOSIS ................................................................................................................................................. 12 BOTULISM, FOODBORNE (β) ....................................................................................................................................... 13 BOTULISM, INFANT (β) ................................................................................................................................................... -

Idiopathic Interstitial Keratitis in a Child 35

Summer 2021 • Vol 16 | No 1 Case report SA Ophthalmology Journal Idiopathic interstitial keratitis in a child 35 Idiopathic interstitial keratitis in a child DA Erasmus MBBCh, MMed, Dip Ophth (SA); Registrar, Department of Neurosciences, Division of Ophthalmology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8395-7080 R Höllhumer MBChB, MMed, FC Ophth(SA); Consultant ophthalmologist, Department of Neurosciences, Division of Ophthalmology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4375-2224 Corresponding author: Dr DA Erasmus, 40 2nd Avenue, Parktown North, 2193; tel.: +27 76 462 3355; email: [email protected] Abstract Interstitial keratitis represents inflammation and new vessel investigations can help to establish the underlying cause of formation in the middle layers of the cornea without tissue interstitial keratitis. loss. The most important infective aetiologies include herpes viruses, tuberculosis and syphilis. Keywords: interstitial, keratitis, inflammation, cornea, stroma Non-infectious causes such as Cogan’s syndrome should be considered in those cases with associated neurosensory Funding: No external funding was received. hearing loss. The pattern and laterality of inflammation together with the Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest presence or absence of systemic features as well as relevant to declare. Severe Mild Moderate Moderate/Mild A * Dry Eye range like NEVER BEFORE Introduction systemic features provides a clue to the a tuberculosis (TB) endemic area such as Interstitial keratitis is a non-ulcerative underlying cause of interstitial keratitis. South Africa. Parasitic infections causing inflammation and subsequent Interstitial keratitis can be broadly interstitial keratitis are very uncommonly vascularisation of the corneal stroma divided into infectious and non-infectious encountered in South Africa but imported which does not primarily involve the aetiologies. -

Immune Defense at the Ocular Surface

Eye (2003) 17, 949–956 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/eye Immune defense at EK Akpek and JD Gottsch CAMBRIDGE OPHTHALMOLOGICAL SYMPOSIUM the ocular surface Abstract vertebrates. Improved visual acuity would have increased the fitness of these animals and would The ocular surface is constantly exposed to a have outweighed the disadvantage of having wide array of microorganisms. The ability of local immune cells and blood vessels at a the outer ocular system to recognize pathogens distance where a time delay in addressing a as foreign and eliminate them is critical to central corneal infection could lead to blindness. retain corneal transparency, hence The first vertebrates were jawless fish that preservation of sight. Therefore, a were believed to have evolved some 470 million combination of mechanical, anatomical, and years ago.1 These creatures had frontal eyes and immunological defense mechanisms has inhabited the shorelines of ancient oceans. With evolved to protect the outer eye. These host better vision, these creatures were likely more defense mechanisms are classified as either a active and predatory. This advantage along with native, nonspecific defense or a specifically the later development of jaws enabled bony fish acquired immunological defense requiring to flourish and establish other habitats. One previous exposure to an antigen and the such habitat was shallow waters where lunged development of specific immunity. Sight- fish made the transition to land several hundred threatening immunopathology with thousand years later.2 To become established in autologous cell damage also can take place this terrestrial environment, the new vertebrates after these reactions. -

Results of Penetrating Keratoplasty in Syphilitic Interstitial Keratitis

RESULTS OF PENETRATING KERATOPLASTY IN SYPHILITIC INTERSTITIAL KERATITIS GOEGEBUER A.*, ***, AJAY LOHIYA**, ***, CLAERHOUT I.*, KESTELYN PH.* ABSTRACT ratite interstitielle (KI) syphilitique avec ceux dé- crits dans la litérature. Purpose: To compare the results in our patient se- Méthode: Analyse rétrospective des cas, avec acui- ries after penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) for syphi- té visuelle, clarté du greffon, épisodes de rejet, pres- litic interstitial keratitis (IK) with those described in sion intraoculaire et comptage postopératoire des the literature. cellules endothéliales. Methods: Retrospective case series in which visual Résultats: L’acuité visuelle s’est améliorée dans tous acuity (VA), graft clarity,rejection episodes, intraocu- les cas. Il n’y avait pas de signes de déhiscence du lar pressure and endothelial cell density (ECD) were greffon, ni d’ occurrence d’une membrane rétrocor- examined postoperatively. néenne. L’inflammation postopératoire n’était pas Results: Postoperative VA improved in all cases. plus prononcée chez nos patients avec une kératite There was no evidence of wound dehiscense or oc- interstitielle comparée aux patients opérés pour currence of retrocorneal membrane formation in any d’autres raisons. Un déclin normal du comptage des case. Postoperative inflammation was not more se- cellules endothéliales prouvait qu’il n’y avait pas d’in- vere in our patients with syphilitic IK compared to flammation infraclinique. patients undergoing PKP for other reasons. A nor- Conclusion: Une kératoplastie transfixiante pour KI mal decline in ECD proved that there was no sub- syphilitique a un bon pronostic en ce qui concerne clinical inflammation as well. la clarté du greffon. Tous les patients bénéficiaient Conclusion: PKP for syphilitic IK has a good prog- d’ une amélioration de l’acuité visuelle, bien que par- nosis in our case series as far as graft survival is con- fois limitée. -

Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection for Corneal Neovascularization in Interstitial Keratitis

perim Ex en l & ta a l ic O p in l h Journal of Clinical & Experimental t C h f a o l m l a o Thakur et al., J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2019, 10:2 n l o r g u y o Ophthalmology J DOI: 10.4172/2155-9570.1000797 ISSN: 2155-9570 Case Report Open Access Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection for Corneal Neovascularization in Interstitial Keratitis Anchal Thakur, Amit Gupta* and Sabia Handa Department of Ophthalmology, Advanced Eye Centre, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Sector 12, Chandigarh, India *Corresponding author: Amit Gupta, Department of Ophthalmology, Advanced Eye Centre, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Sector 12, Chandigarh, India, Tel: 0172 274 7585; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: January 31, 2019; Accepted date: March 19, 2019; Published date: March 26, 2019 Copyright: ©2019 Thakur A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract We describe the use of subconjunctival Bevacizuamb as an adjunct in the treatment of viral interstitial keratitis in a 17-year-old boy. He presented with a 3 months history of gradually progressive diminution of vision. The presenting visual acuity was 20/120 in the right eye and counting fingers close to face in the left eye. Examination revealed bilateral disc shaped stromal edema with leash of blood vessels entering the superior quadrant of the cornea. Subconjunctival injection of 0.1 mL (2.5 mg) of commercially available Bevacizumab (100 mg/4 mL; Avastin) was given under topical anesthesia along with initiation of topical steroids in the form of Betamethasone 0.1%. -

Clinical Manifestations and Outcome of Tuberculous Sclerokeratitis Samir S Shoughy,1 Mahmoud O Jaroudi,1 Khalid F Tabbara1,2,3

Downloaded from http://bjo.bmj.com/ on August 30, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com Clinical science Clinical manifestations and outcome of tuberculous sclerokeratitis Samir S Shoughy,1 Mahmoud O Jaroudi,1 Khalid F Tabbara1,2,3 1The Eye Center and The Eye ABSTRACT uncommon.4 Tuberculosis of the anterior segment Foundation for Research in Aim To study the clinical manifestations and outcome of the eye may lead to a variety of clinical manifes- Ophthalmology, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia of patients with tuberculous sclerokeratitis treated with tations and may affect the eyelids, the orbit, the lac- 2Department of antituberculous therapy without concomitant use of rimal gland, the cornea, the sclera or the Ophthalmology, College of systemic steroids. conjunctiva.35 Medicine, King Saud Methods We reviewed retrospectively the medical Tuberculosis may affect the cornea leading to University, Riyadh, Saudi records of eight consecutive patients with tuberculous interstitial keratitis or disciform keratitis.67 Arabia 3The Wilmer Ophthalmological sclerokeratitis. Patients were treated unsuccessfully with Similarly, scleral involvement in tuberculosis may Institute of The Johns Hopkins topical and/or systemic steroids. They underwent occur as a localised lesion. Tuberculosis may affect University, School of Medicine, complete ophthalmic examination, systemic evaluation, the sclera and the adjacent corneal periphery Baltimore, Maryland, USA laboratory investigations and imaging. Tuberculin skin leading to sclerokeratitis, which may occur in other fi Correspondence -

Official Updates to Icd-10

Ratified by HoC/WHO at the HoC meeting in Washington, October 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Update Reference Committee 30 November 2001 OFFICIAL UPDATES TO ICD-10 The following pages include the official changes to the tabular list, instruction manual and alphabetical index of ICD-10. These changes were approved in principle at the HoC meeting in Washington DC, October 2001. Each change has been uniquely identified and the source for each change has been indicated. The implementation date has also been documented. (Note: Every effort has been made in the following pages to reproduce the content of the ICD-10 in the same format as the published volumes. Page references have not been used in all instances since these do not apply to electronic versions of the Classification. Additions/changes have been indicated through the use of instructions, underline and strikeout). This document is not issued to the general public, and all rights are reserved by the World Health Organization (WHO). The document may not be reviewed, abstracted, quoted, reproduced or translated, in part or in whole, without the prior written permission of WHO. No part of this document may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical or other – without the prior written permission of WHO. Page 1 Ratified by HoC/WHO at the HoC meeting in Washington, October 2001 Volume 1 TABULAR LIST Instruction Tabular list entries Source Major/Minor Implementation update date Delete dagger A02.2 † Localized salmonella infections Australia Minor January 2003 Salmonella: (URC:0046) Add dagger . -

Lacrimal Excretory System Sequelae in Patients Treated for Leishmaniasis

Lacrimal excretory system sequelae in patients treated for leishmaniasis Alterações como seqüelas no sistema lacrimal de portadores de leishmaniose tratada Erika Hoyama1 ABSTRACT Silvana Artioli Schellini2 Hamilton Ometo Stolf3 Leishmaniasis infection may involve destruction of nasal tissues resulting 4 Vitor Nakajima in lacrimal drainage system alteration. Purpose: To evaluate the frequency of lacrimal excretory system sequelae in patients treated for leishmaniasis. Methods: Forty-five leishmaniasis-treated patients (90 nasolacrimal ducts) were submitted to lacrimal excretory system evaluation. All were evaluated by Jones I test and when it was abnormal, dacryocystography and nasal endoscopy were performed. This situation occurred in 13 patients (26 nasolacrimal ducts). Results: The majority of evaluated patients had the cutaneous form (64.4%) of leishmaniasis, however, 69.23% of the patients with lacrimal excretory system alterations had the mucocutaneous form of infection before treatment. In these, the most common alteration detected was bilateral permeable and dilated nasolacrimal ducts (92.30%). Only 3.84% (1/26) of the evaluated nasolacrimal ducts were obstructed. Nasal endoscopy showed turbinate hypertrophy (53.84%), septum de- viation (53.84%) and nasal septum perforation (23.07%). Conclusion: Permeable and dilated lacrimal excretory system were the most common sequelae related to leishmaniasis infection. Keywords: Leishmaniasis/complications; Lacrimal duct obstruction/radiography; Endos- copy/methods; Nasal cavity/radiography INTRODUCTION This study was performed at the Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu. Leishmaniasis is one of the six major endemic tropical diseases with a (1-2) 1 Pós-Graduanda - Departamento de Oftalmologia, Otorri- prevalence of 12 million cases worldwide . The disease is widespread in nolaringologia e Cirurgia de Cabeça e Pescoço da Facul- Latin America where it constitutes a major public health problem. -

Cornea and External Disease Robert Cykiert, M.D

Cornea and External Disease Robert Cykiert, M.D. I. Basics papilla vascular response if giant, the differential includes atopy, vernal, GPC, prosthesis, suture follicles lymphatic response acute chronic EKC, pharygoconjunctival fever adult inclusion conjunctivitis medicamentosa (epinephrine, neosynephrine) toxic Parinaud's oculoglandular,syndrome r/o sarcoid HSV primary conjunctivitis r/o GPC, vernal conjunctivitis Newcastle's conjunctivitis with acute follicles, always check lid margin for HSV vesicles, ulcers membranes conjunctivitis ocular cicatricial pemphigoid erythema multiforme Stevens Johnson syndrome Srogrens syndrome atopy Symblepharon scieroderrna burns radiation burns trachoma EKC sarcoid drugs filaments exposure (keratoconjunctivitis sicca, neurotrophic, patching recurrent erosion) bullous keratopathy HSV meds superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis psoriasis aerosol keratitis diabetes mellitus radiation retained FB Thygeson's SPK ptosis Enlarged Corneal nerves MEN TIIb icthyosis Hanson's Kconus Refsums Fuchs corneal dystrophy old age failed PKP congenital glaucoma trauma neurofibromatosis MEN TIIb AD with thick corneal nerves, medullary thyroid cancer, pheochromocytoma, mucosal neuromas, and marfanoid habitus thickened lid margin with rostral lashes, thick lips, epibulbar neuromas cafe au lait spots, periungual, lingual neuromas often confused with NFI often die early from amyloid producing thyroid cancer in 10-20 year old with distant mets at dx thick nerves precede the cancer! corneal edema whenever epithelium disrupted, -

Infiltrative Keratitis: Etiology, Diagnosis & Management

7/23/2015 Terry E. Burris, MD Northwest Corneal Services Portland, OR Co- Medical Director, Lions VisionGift Oregon Associate Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology Oregon Health Sciences University 1 Infiltrative Keratitis: Etiology, Diagnosis & Management 1 7/23/2015 Epidemiology Outline Ulcerative Keratitis -Infiltrative Infectious Non-infectious Survey of Infectious and Non-infectious etiologies Brief Review of Laboratory Methods Practical Guide to Empiric Treatment of: Bacterial ulcers Fungal ulcers Culture-driven treatment brief Antiviral Treatment of Infiltrative Keratitis Update HSV Adenovirus Epidemiology of Ulcerative Keratitis Annual incidence – >500,000 worldwide – >30,000 USA Complications of sight limiting corneal opacification (scarring 2nd most common cause of vision loss worldwide): – >1 Million worldwide – >100,000 N. America 2 7/23/2015 The Social Acuity Chart Epidemiology of Ulcerative Keratitis Contact lens–related infectious keratitis – ~50% result in reduced vision – Corneal opacification +/- perforation 330 transplants per year USA Worldwide epidemic of corneal blindness from infectious keratitis Whitcher, Srinivasan, Upadhyay: Corneal blindess: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:214-221 3 7/23/2015 Epidemiology of Ulcerative Keratitis Contact lens-associated Bacterial Keratitis 35-40 Million wearers in USA Majority fail at least in 1 aspect of contact lens hygiene Biofilm formation on contact lens and case Potentiates infection by blocking antibiotics Unchecked bacterial proliferation