The Laws of Design in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Liz Falletta ______

Liz Falletta _____________________________________________________________________________________ CONTACT University of Southern California Phone: (213) 740 - 3267 INFORMATION Price School of Public Policy Mobile: (323) 683 - 6355 Ralph and Goldy Lewis Hall, 240 Email: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90089-0626 Date: January 2015 TEACHING University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA APPOINTMENTS Price School of Public Policy Associate Professor (Teaching), July 2014 – present Assistant Professor (Teaching), January 2009 – May 2014 Clinical Assistant Professor, July 2007 – December 2008 Lecturer, June 2004 – June 2007 Iowa State University, Ames, IA College of Design, Department of Architecture Visiting Lecturer, January 2003 – May 2003 University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA School of Architecture and Urban Design Co-Instructor (with Mark Mack), October 2002 – December 2002 Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), Los Angeles, CA Instructor, August 2000 – December 2000 Associate Instructor, June 2000 – August 2000 EDUCATION University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA Master of Real Estate Development, 2004 Southern California Institute of Architecture, Los Angeles, CA Master of Architecture, 2000 Washington University, St. Louis, MO Bachelor of Arts in Architecture, Philosophy Minor, magna cum laude, 1993 COURSES University of Southern California TAUGHT Price School of Public Policy Design History and Criticism (RED 573), Summer 2004 – present Community Development and Site Planning (PPD -

Pleksiglass Som Lokke Mat Og Mulighet Plexiglas As a Lure And

Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Plexiglas as a lure and Plexiglas potential By Liam Gillick Den britiske kunstneren Liam Gillick har gjerne The British artist Liam Gillick is often associated as a lure and blitt forbundet med den relasjonelle estetikken, with relational aesthetics, which emphasises the som la vekt på betrakteren som medskaper av ver- contribution of the viewer to an artwork and tends ket, og som ofte handlet om å tilrettelegge steder to focus on defining places and situations for social og situasjoner for sosial interaksjon. Men i mot- interaction. But in contrast to artists like Rirkrit setning til kunstnere som Rirkrit Tiravanija, som Tiravanija, who encourages audience-participation inviterte publikum til å samtale over et måltid, in a meal or a conversation, Gillick’s scenarios do gir ikke Gillicks scenarier inntrykk av å være laget not seem constructed for human activity. Instead, for menneskelig aktivitet. Installasjonene hans i his installations of Plexiglas and aluminium are potential pleksiglass og aluminium handlere snarere om concerned with the analysis of structures and types å analysere sosiale strukturer og organisasjons- of social organisation, and with the exploration of måter, og undersøke de romlige forutsetningene the spatial conditions for human interaction. Rec- for menneskelig interaksjon. Inspirert av hans ognising Gillick’s carefully considered relationship reflekterte forhold til materialene han jobber to the materials he uses, we invited him to write By med, ba vi ham skrive om sin interesse for pleksi- about his interest in Plexiglas, a material he has glass, et materiale han har arbeidet med i over 30 år. -

Introduction

Introduction One way to understand the ongoing amplification and extension of design is to see how it is being driven by market and societal demand. With a public that is familiar with design thinking and social design, there is a kind of design renaissance today where those who are not necessarily from within the design community see its value. This “pull” that design currently enjoys is evident in several ways: those working in consultancies are adding a more Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/desi/article-pdf/36/2/1/1716215/desi_e_00584.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 balanced approach to traditional business-heavy perspectives at the request of more sophisticated clients; those in corporations are building in-house design capabilities to meet the needs of their internal constituents; and those working in and for non-profits are translating and facilitating authentic insights regarding the underserved who desire to be engaged in more humane and equi- table ways. There is another way that design continues to expand and it is through its own “push” mechanism. It is a healthy sign when a discipline—not seeking to rest on its own laurels—takes on a con- tinuous and collective reflection-in-action. Like the concept of a learning organization, designers are busy pushing beyond their own set of boundaries, approaching design itself as a learning dis- cipline where action and course correction are constantly at play. The authors in this issue, adopting the latter approach to developing design, push themselves and the discipline beyond the status quo. Though they use different terms to describe the idea of incompleteness and the opportunity to expand, their message is uniform: design is but one dimension in our complex world and yet it serves an important function in the shaping of larger wholes. -

Form, Function and Symbolism in Furniture Design, Fictive Eroision and Social Expectations

shutter speed form, function and symbolism in furniture design, fictive eroision and social expectations SHUTTER SPEED Form, function and symbolism in furniture design, fictive erosion and social expectations SHUTTER SPEED Form, function and symbo lism in furniture design, fictive erosion and social expectations Kajsa Melchior MA Spatial Design Diploma project VT 2019 Konstfack Kajsa Melchior MA Spatial Design Diploma project VT 2019 Konstfack The concept of time is central to geological thought. The processes that shape the surface of the earth acts over vast expenses of time - millions, or even billions of years. If we discount, for the moment, catastrophic events such as earthquakes and landslides, the earth's surface seems relatively stable over the timescales we can measure. Historical records do show the slow diversion of a rivers course, and the silting up of estuaries, for example. But usually we would expect images taken a hundred years ago to show a landscape essentially the same as today's. But imagine time speeding up, so that a million years pass in a minute. In this time frame, we would soon lose our concept of 'solid' earth, as we watch the restless surface change out of all recognition. - Earth’s restless surface, Deirdre Janson-Smith, 1996 1 Table of contents 1. PRELUDE 1.1 Aims, intentions and questions 05-06 1.2 Background 07 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK - REFERENCES 2.1 Philosophy / Étienne Jules Marey 09-10 2.2 Aesthetics / Max Lamb 11-12 2.3 Criticism / Frederick Kiesler 13-14 2.4 Conclusion 15 3. FICTIVE EROSION 3.1 Methodology as tool 16 3.3 Erosion & Casting techniques 16-18 3.4 Method 19-23 4. -

Narrative Problems of Graphic Design History

233 Victor Margolin Narrative Problems of Graphic Design History The problem of method in the construction of narratives is particularly acute in the field of graphic design history. Various publications have brought attention to the subject of graphic design history, but have not marked a course for the full explanation of how graphic design developed as a practice. Three major texts by Philip Meggs, Enric Satue and Richard Hollis address the history of graphic design, but each raises questions about what material to include, as well as how graphic design is both related to and distinct from other visual practices such as typography, art direction and illustra Victor Margolin is associate professor tion. The author calls for a narrative strategy that is of design history at the University of Illinois, Chicago. He is editor of more attentive to these distinctions and probes more Design Discourse: History, Theory, deeply into the way that graphic design has evolved . Criticism, author ofThe American Poster Renaissance and co-editor of Discovering Design : Explorations in Design Studies (forthcoming). Professor Margolin is also a founding editor of the journal Design Issues. University of Ill inois, Chicago School of Art and Design m/c 036 Chicago Illinois 60680 Visible Language, 28:3 Victor Margolin, 233·243 © Visible Language, 1994 Rhode Island School of Design Providence Rhode Island 02903 234 Visible Language 28.3 Narrativity becomes a problem only when we wish to give real events the form of a story.' Introduction In recent years scholars have devoted considerable attention to the study of narrative structures in history and fiction. -

Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism As a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union

Momentum Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 6 2018 Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Robert Levine University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum Recommended Citation Levine, Robert (2018) "Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union," Momentum: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Abstract This paper examines the role of architecture in the promotion of political ideologies through the study of modern architecture in the 20th century. First, it historicizes the development of modern architecture and establishes the style as a tool to convey progressive thought; following this perspective, the paper examines Swedish Functionalism and Constructivism in the Soviet Union as two case studies exploring how politicians react to modern architecture and the ideas that it promotes. In Sweden, Modernism’s ideals of moving past “tradition,” embracing modernity, and striving to improve life were in lock step with the folkhemmet, unleashing the nation from its past and ushering it into the future. In the Soviet Union, on the other hand, these ideals represented an ideological threat to Stalin’s totalitarian state. This thesis or dissertation is available in Momentum: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 Levine: Modern Architecture & Ideology Modern Architecture & Ideology Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Robert Levine, University of Pennsylvania C'17 Abstract This paper examines the role of architecture in the promotion of political ideologies through the study of modern architecture in the 20th century. -

Department of Art & Design

Whitburn Academy Department of Art & Design Art & Design Studies Learners Higher: Art & Design Studies Design Analyse the factors influencing designers and design practice by Booklet Fashion 1.1 Describing how designers use a range of design materials, techniques and technology in their work 1.2 Analysing the impact of the designers’ creative choices in a range of design work 1.3 Analysing the impact of social and cultural influences on selected designers and their design practice. A study of Coco Chanel Day dress, ca. 1924 Gabrielle Theater suit, 1938, Gabrielle Evening dress, ca. 1926–27 "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883–1971) "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883– Attributed to Gabrielle "Coco" Wool 1971) Silk Chanel (French, 1883–1971) Silk, metallic threads, sequins What is Fashion Design? Fashion design is a form of art dedicated to the creation of clothing and other lifestyle accessories. Modern fashion design is divided into two basic categories: haute couture and ready-to-wear. The haute couture collection is dedicated to certain customers and is custom sized to fit these customers exactly. In order to qualify as a haute couture house, a designer has to be part of the Syndical Chamber for Haute Couture and show a new collection twice a year presenting a minimum of 35 different outfits each time. Ready-to-wear collections are standard sized, not custom made, so they are more suitable for large production runs. They are also split into two categories: designer/creator and confection collections. Designer collections have a higher quality and finish as well as an unique design. They often represent a certain philosophy and are created to make a statement rather than for sale. -

Lighting for the Workplace

Lighting for the Workplace AWB_Workplace_Q_Produktb_UK.qxd 02.05.2005 10:35 Uhr Seite 3 CONTENTS 3 Foreword by Paul Morrell, 4–5 President of the British Council for Offices INTRODUCTION 6–7 The Changing Corporate Perspective 6–7 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE 8–51 Lighting Research versus the Codes 10–11 – The Lessons of Lighting Research 12–15 – Current Guidance and its Limitations 16–23 Key Issues in Workplace Lighting 24–29 Natural Light, Active Light & Balanced Light 30–37 Further Considerations in Workplace Lighting 38–47 Lighting Techniques – Comparing the Options 48–51 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – APPLICATION AREAS 52–97 Open Plan Offices 56–67 Cellular Offices 68–71 Dealer Rooms 72–75 Control Rooms 76–79 Call Centres 80–83 Communication Areas/Meeting Rooms 84–87 Break-Out Zones 88–91 Storage 92–93 Common Parts 94–97 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – LIGHTING DESIGN 98–135 Product Selector 100–133 Advisory Services 134–135 References & Useful Websites 135 IMPRINT Publisher: Zumtobel Staff GmbH, Dornbirn/A Design: Marketing Communication Reprints, even in part, require the permission of the publishers © 2005 Zumtobel Staff GmbH, Dornbirn/A Paul Morrell President of the British Council for Offices (BCO) London aims to continue being Europe’s leading financial centre and will need more, higher quality office space in the future (photo: Piper’s model of the future City of London, shown at MIPIM 2005) FOREWORD 5 The UK office market, in particular in London, is changing, driven by a number of long-term trends in international banking and finance. Informed forecasts, such as the recent Radley Report*, point, firstly, to a shift towards our capital city, at the expense of Paris and Frankfurt, as Europe’s leading financial centre, with a commensurate pressure on office space. -

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA University of North Carolina at Charlotte Invitation for Bid # 66-190015RL Miltimore-Wallis Center Roof Replacement Date of Issue: August 16, 2018 Bid Opening Date: Thursday, August 30, 2018 At 2:00 PM ET Direct all inquiries concerning this IFB to: Robert Law Senior Buyer Email: [email protected] STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHARLOTTE Invitation for Bids # 66-190015RL ______________________________________________________ For internal State agency processing, including tabulation of bids in the Interactive Purchasing System (IPS), please provide your company’s Federal Employer Identification Number or alternate identification number (e.g. Social Security Number). Pursuant to G.S. 132-1.10(b) this identification number shall not be released to the public. This page will be removed and shredded, or otherwise kept confidential, before the procurement file is made available for public inspection. This page is to be filled out and returned with your bid. Failure to do so may subject your bid to rejection. ID Number: ______________________________________________________ Federal ID Number or Social Security Number ______________________________________________________ Vendor Name STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA University of North Carolina at Charlotte Refer ALL Inquiries regarding this IFB to: Invitation for Bids # 66-190015RL Robert Law Bids will be publicly opened: Senior Buyer Thursday, August 30, 2018 @ 2:00 PM ET [email protected] Contract Type: Open Market Using Department: Facilities Management, Design Services EXECUTION In compliance with this Invitation for Bids, and subject to all the conditions herein, the undersigned Vendor offers and agrees to furnish and deliver any or all items upon which prices are bid, at the prices set opposite each item within the time specified herein. -

Teasley, Sarah. "“Methods of Reasoning and Imagination

Teasley, Sarah. "“Methods of Reasoning and Imagination”: History’s Failures and Capacities in Anglophone Design Research." Theories of History: History Read across the Humanities. By Michael J. Kelly and Arthur Rose. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. 183–206. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474271332.ch-010>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 02:53 UTC. Copyright © Michael J. Kelly, Arthur Rose, and Contributors 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 10 “Methods of Reasoning and Imagination”: History’s Failures and Capacities in Anglophone Design Research Sarah Teasley This chapter critically explores the place of history as concept and practice within the field of design research, past and present. Design, today, refers to a spectrum of practices varying widely in medium, scale, and application. Alongside famil- iar forms such as architecture, fashion, interiors, graphic, product, industrial, textile, engineering, and systems design and urban planning, practices such as interaction design, service design, social design, and speculative critical design have emerged in the past decade, alongside new forms of technology, new inter- faces, new economic and political landscapes, and new ideas about the roles that design can play in society and the economy.1 In its expanded practice, design shapes, creates, and implements material and immaterial artefacts, not only the buildings, chairs, and garments familiar to us as “design” but public policy, cor- porate strategy, and social behavior.2 On a more abstract level, design is both verb and noun, both action and the product of action. -

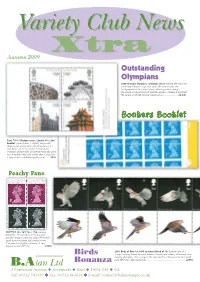

VCN Autumn 2009.Pmd

VarietyVariety ClubClub NewsNews XtraXtra Autumn 2009 Outstanding Olympians 2008 Olympic Handover miniature sheet missing the shiny uv varnished Olympic rings that normally stretch over the background of the entire sheet, affecting every stamp. Previously unrecorded and possibly unique, making it amongst the rarest of all GB missing colour errors ..................... £6,500 Bonkers Booklet Type 7(10) Olympic cover, Questa 10 x 2nd booklet, pane shows a slightly diagonally downwards perforation shift of between 6.5 and 8mm on every stamp. A few minor wrinkles, presumably occurring when the pane was misperforated, but barely detracting from a spectacular exhibition quality item ...... £950 Peachy Pane OCP/PVA 1p +1p/1½p + 1½p, missing phosphor. Previously unrecorded and possibly unique, perfs are good all around apart from the lower-left corner of one 1½p which is slightly trimmed. A very important find [DP2/N] ..................... £2950 2003 Birds of Prey 1st AOP se-tenant block of 10, bottom row of 5 Birds stamps missing brownish grey Queen’s heads and values, all stamps also missing phosphor. One stamp in the top row has a bonus error of a small B.Alan Ltd Bonanza oval litho flaw! Rare [2327ab] ............................................................ £1750 2 Pinewood Avenue ◆ Sevenoaks ◆ Kent ◆ TN14 5AF ◆ UK Tel: 01732 743387 ◆◆◆ Fax: 01732 465651 ◆◆◆ E-mail: [email protected] WELCOME Welcome to Variety Club News Xtra. The list is split into two main parts, the latest issues as supplied on our recent S distribution new issue sendings towards the back and nearer the front a selection of items chosen from stock including interesting and better items, most of which are more elusive, and some of which are one off pieces that do not fall within the scope of standard catalogues, making them highly desirable and extremely unlikely to be offered again.