Form, Function and Symbolism in Furniture Design, Fictive Eroision and Social Expectations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privacy When Form Doesn't Follow Function

Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function Roger Allan Ford University of New Hampshire [email protected] Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function—discussion draft—3.6.19 Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function Scholars and policy makers have long recognized the key role that design plays in protecting privacy, but efforts to explain why design is important and how it affects privacy have been muddled and inconsistent. Tis article argues that this confusion arises because “design” has many different meanings, with different privacy implications, in a way that hasn’t been fully appreciated by scholars. Design exists along at least three dimensions: process versus result, plan versus creation, and form versus function. While the literature on privacy and design has recognized and grappled (sometimes implicitly) with the frst two dimensions, the third has been unappreciated. Yet this is where the most critical privacy problems arise. Design can refer both to how something looks and is experienced by a user—its form—or how it works and what it does under the surface—its function. In the physical world, though, these two conceptions of design are connected, since an object’s form is inherently limited by its function. Tat’s why a padlock is hard and chunky and made of metal: without that form, it could not accomplish its function of keeping things secure. So people have come, over the centuries, to associate form and function and to infer function from form. Software, however, decouples these two conceptions of design, since a computer can show one thing to a user while doing something else entirely. -

Introduction: Design Epistemology

Design Research Society DRS Digital Library DRS Biennial Conference Series DRS2016 - Future Focused Thinking Jun 17th, 12:00 AM Introduction: Design Epistemology Derek Jones The Open University Philip Plowright Lawrence Technological University Leonard Bachman University of Houston Tiiu Poldma Université de Montréal Follow this and additional works at: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/drs-conference-papers Citation Jones, D., Plowright, P., Bachman, L., and Poldma, T. (2016) Introduction: Design Epistemology, in Lloyd, P. and Bohemia, E. (eds.), Future Focussed Thinking - DRS International Conference 20227, 27 - 30 June, Brighton, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.619 This Miscellaneous is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at DRS Digital Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in DRS Biennial Conference Series by an authorized administrator of DRS Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction: Design Epistemology Derek Jonesa*, Philip Plowrightb, Leonard Bachmanc and Tiiu Poldmad a The Open University b Lawrence Technological University c University of Houston d Université de Montréal * [email protected] DOI: 10.21606/drs.2016.619 “But the world of design has been badly served by its intellectual leaders, who have failed to develop their subject in its own terms.” (Cross, 1982) This quote from Nigel Cross is an important starting point for this theme: great progress has been made since Archer’s call to provide an intellectual foundation for design as a discipline in itself (Archer, 1979), but there are fundamental theoretical and epistemic issues that have remained largely unchallenged since they were first proposed (Cross, 1999, 2007). -

Fashion Design

FASHION DESIGN FAS 112 Fashion Basics (3-0) 3 crs. FAS Fashion Studies Presents fashion merchandise through evaluation of fashion products. Develops awareness of construction, as well as FAS 100 Industrial Sewing Methods (1-4) 3 crs. workmanship and design elements, such as fabric, color, Introduces students to basic principles of apparel construction silhouette and taste. techniques. Course projects require the use of industrial sewing equipment. Presents instruction in basic sewing techniques and FAS 113 Advanced Industrial Sewing Methods (1-4) 3 crs. their application to garment construction. (NOTE: Final project Focuses on application and mastery of basic sewing skills in should be completed to participate in the annual department Little pattern and fabric recognition and problem solving related to Black Dress competition.) individual creative design. Emphasis on technology, technical accuracy and appropriate use of selected materials and supplies. FAS 101 Flat Pattern I (1-4) 3 crs. (NOTE: This course is intended for students with basic sewing Introduces the principles of patternmaking through drafting basic skill and machine proficiency.) block and pattern manipulation. Working from the flat pattern, Prerequisite: FAS 100 with a grade of C or better or placement students will apply these techniques to the creation of a garment as demonstrated through Fashion Design Department testing. design. Accuracy and professional standards stressed. Pattern Contact program coordinator for additional information. tested in muslin for fit. Final garment will go through the annual jury to participate in the annual department fashion show. FAS 116 Fashion Industries Career Practicum and Seminar Prerequisite: Prior or concurrent enrollment in FAS 100 with a (1-10) 3 crs. -

Theoretically Comparing Design Thinking to Design Methods for Large- Scale Infrastructure Systems

The Fifth International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC2018) Bath, UK, January 31st – February 2nd 2018 THEORETICALLY COMPARING DESIGN THINKING TO DESIGN METHODS FOR LARGE- SCALE INFRASTRUCTURE SYSTEMS M.A. Guerra1 and T. Shealy1 1Civil Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, USA Abstract: Design of new and re-design of existing infrastructure systems will require creative ways of thinking in order to meet increasingly high demand for services. Both the theory and practice of design thinking helps to exploit opposing ideas for creativity, and also provides an approach to balance stakeholder needs, technical feasibility, and resource constraints. This study compares the intent and function of five current design strategies for infrastructure with the theory and practice of design thinking. The evidence suggests the function and purpose of the later phases of design thinking, prototyping and testing, are missing from current design strategies for infrastructure. This is a critical oversight in design because designers gain much needed information about the performance of the system amid user behaviour. Those who design infrastructure need to explore new ways to incorporate feedback mechanisms gained from prototyping and testing. The use of physical prototypes for infrastructure may not be feasible due to scale and complexity. Future research should explore the use of prototyping and testing, in particular, how virtual prototypes could substitute the experience of real world installments and how this influences design cognition among designers and stakeholders. Keywords: Design thinking, design of infrastructure systems 1. Introduction Infrastructure systems account for the vast majority of energy use and associated carbon emissions in the United States (US EPA, 2014). -

Design Thinking Methods and Techniques in Design Education

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 7 & 8 SEPTEMBER 2017, OSLO AND AKERSHUS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF APPLIED SCIENCES, NORWAY DESIGN THINKING METHODS AND TECHNIQUES IN DESIGN EDUCATION Ana Paula KLOECKNER1, Cláudia de Souza LIBÂNIO1,2 and José Luis Duarte RIBEIRO1 1PPGEP/UFRGS, Brazil 2UFCSPA, Brazil ABSTRACT Design Thinking is a human-centred innovation process, with an emphasis on deep understanding of consumers, holistically, integratively, creatively, and awe-inspiring. Design Thinking methods and techniques represents how the theory will be operationalized by following the process steps. These methods and techniques can assist in the project management, especially in the initial phase of inspiration and ideation. Another strategy that can collaborate in project management is agile management, mainly in the execution phase of a project. Agile management prioritizes individuals, interactions between them, customers, appropriate software to operate, and prompt response to changes. Thus, this study aims to propose a model to integrate design thinking and project management methods and techniques and to analyze students’ projects and interactions to verify the applicability of these in ergonomic project management. For the development of the method, it was used the design science methodology, in four main steps called: Research Clarification, Descriptive Study I, Prescriptive Study, and Descriptive Study II. From the use of tools and techniques of design thinking in a project management exercise for students of two classes, it was revealed that the tools used facilitated the project development, helping from the search and organization of information until the deadline established for the delivery of the project. Keywords: Design Thinking, Design Education, Project Management. -

Pleksiglass Som Lokke Mat Og Mulighet Plexiglas As a Lure And

Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Plexiglas as a lure and Plexiglas potential By Liam Gillick Den britiske kunstneren Liam Gillick har gjerne The British artist Liam Gillick is often associated as a lure and blitt forbundet med den relasjonelle estetikken, with relational aesthetics, which emphasises the som la vekt på betrakteren som medskaper av ver- contribution of the viewer to an artwork and tends ket, og som ofte handlet om å tilrettelegge steder to focus on defining places and situations for social og situasjoner for sosial interaksjon. Men i mot- interaction. But in contrast to artists like Rirkrit setning til kunstnere som Rirkrit Tiravanija, som Tiravanija, who encourages audience-participation inviterte publikum til å samtale over et måltid, in a meal or a conversation, Gillick’s scenarios do gir ikke Gillicks scenarier inntrykk av å være laget not seem constructed for human activity. Instead, for menneskelig aktivitet. Installasjonene hans i his installations of Plexiglas and aluminium are potential pleksiglass og aluminium handlere snarere om concerned with the analysis of structures and types å analysere sosiale strukturer og organisasjons- of social organisation, and with the exploration of måter, og undersøke de romlige forutsetningene the spatial conditions for human interaction. Rec- for menneskelig interaksjon. Inspirert av hans ognising Gillick’s carefully considered relationship reflekterte forhold til materialene han jobber to the materials he uses, we invited him to write By med, ba vi ham skrive om sin interesse for pleksi- about his interest in Plexiglas, a material he has glass, et materiale han har arbeidet med i over 30 år. -

Design Methods for Democratising Mobile Game Design

Design Methods for Democratising Mobile Game Design Mark J. Nelson Abstract Swen E. Gaudl Playing mobile games is popular among a large and Simon Colton diverse set of players, contrasting sharply with the lim- Rob Saunders ited set of companies and people who design them. We Edward J. Powley would like to democratise mobile game design by ena- Peter Ivey bling players to design games on the same devices they Blanca Pérez Ferrer play them on, without needing to program. Our concept Michael Cook of fluidic games aims to realise this vision by drawing on three design methodologies. The interaction style of The MetaMakers Institute fluidic games is that of casual creators; their end-user Falmouth University design philosophy is adapted from metadesign; and Cornwall, UK their technical implementation is based on parametric metamakersinstitute.com design. In this short article, we discuss how we’ve adapted these three methods to mobile game design, and some open questions that remain in order to em- power end user game design on mobile phones in a way that rises beyond the level of typical user- generated content. Author Keywords Mobile games; casual creators; metadesign; parametric design; end-user creativity; mixed-initiative interfaces. ACM Classification Keywords H.5.m. Information interfaces and presentation: Miscel- laneous Introduction Fluidic Games Our starting point is the observation that mobile games To support on-device casual design, we are developing have attracted a large and diverse set of players, but a what we call fluidic games [5-7]. These blur the line smaller and less diverse set of designers. -

Design Methods: Seeds of Human Futures

Design Methods: seeds of human futures By John Chris Jones 1970, John Wiley and Sons, New York and Chichester An introductory lecture for digital designers by Rhodes Hileman (c) 1998 “Jones first became involved with design methods The era of “Craft Evolution” while working as an industrial designer for a manufacturer of large electrical products in Britain This wagon (figure 2.1) is a fine example of craft in the 1950s. He was frustrated with the evolution, the first of the four eras identified. superficiality of industrial design at the time and Before the Renaissance, the craftsman carried in had become involved with ergonomics. ... When his head a set of rules about the design of the tools the results of his ergonomic studies of user of the day, which roughly described a useful behavior were not utilized by the firm’s designers, artefact with “invisible lines”, which limited the Jones set about studying the design process being dimensions and shapes of the parts in relation to used by the engineers. To his surprise, and to the whole tool. Designs were slowly evolving in a theirs, Jones’ analysis showed that the engineers living collective knowledge base, and few had no way of incorporating rationally arrived at craftsmen made any major changes. Design was data early on in the design process when it was limited very closely to the neighborhood of the most needed. Jones then set to work redesigning tried and true. the engineer’s design process itself so that intuition and rationality could co-exist, rather than one As an example of the sketchy understanding of excluding the other.” ...and this became a design which craftsmen had, Jones cites George consistent thread throughout his work. -

Changing Cultures of Design Identifying Roles in a Co-Creative Landscape

Changing Cultures of Design Identifying roles in a co-creative landscape Marie Elvik Hagen Department of Product Design Norwegian University of Science and Technology ABSTRACT The landscape of design is expanding and designers today are moving from expert practice to work with users as partners on increasingly complex issues. This article draws up the lines of the emerging co-creative design practice, and discusses the changing roles of the designer, the user as a partner, and design practice itself. Methods and tools will not be considered, as the roles will be discussed in terms of their relations. The co-design approach breaks down hierarchies and seeks equal participation. Research suggests that the designer needs to be responsive or switch tactics in order to take part in a co-creative environment. A case study exploring co-creative roles complements the theory, and finds that the designer role needs to be flexible even when having equal agency as partners and other stakeholders. Sometimes it is necessary to lead and facilitate as long as it is a collaborative decision. Bringing users in as partners in the process changes the design culture, and this article suggests that Metadesign can be the holistic framework that the design community need in order to understand how the different design practices are connected. KEYWORDS: Co-design, Co-creativity, Roles in the Design Process, Participatory Design, Metadesign, Cultures of participation, Design Agenda 1. INTRODUCTION This article seeks to examine how the role of the designer, the role of the user and the role The landscape of design is changing. -

Department of Art & Design

Whitburn Academy Department of Art & Design Art & Design Studies Learners Higher: Art & Design Studies Design Analyse the factors influencing designers and design practice by Booklet Fashion 1.1 Describing how designers use a range of design materials, techniques and technology in their work 1.2 Analysing the impact of the designers’ creative choices in a range of design work 1.3 Analysing the impact of social and cultural influences on selected designers and their design practice. A study of Coco Chanel Day dress, ca. 1924 Gabrielle Theater suit, 1938, Gabrielle Evening dress, ca. 1926–27 "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883–1971) "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883– Attributed to Gabrielle "Coco" Wool 1971) Silk Chanel (French, 1883–1971) Silk, metallic threads, sequins What is Fashion Design? Fashion design is a form of art dedicated to the creation of clothing and other lifestyle accessories. Modern fashion design is divided into two basic categories: haute couture and ready-to-wear. The haute couture collection is dedicated to certain customers and is custom sized to fit these customers exactly. In order to qualify as a haute couture house, a designer has to be part of the Syndical Chamber for Haute Couture and show a new collection twice a year presenting a minimum of 35 different outfits each time. Ready-to-wear collections are standard sized, not custom made, so they are more suitable for large production runs. They are also split into two categories: designer/creator and confection collections. Designer collections have a higher quality and finish as well as an unique design. They often represent a certain philosophy and are created to make a statement rather than for sale. -

Design Research Quarterly Volume 2 Issue 1

Design Research Society DRS Digital Library Design Research Quarterly DRS Archive 1-1-2007 Design Research Quarterly Volume 2 Issue 1 Peter Storkerson Follow this and additional works at: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/design-research-quarterly Recommended Citation Storkerson, Peter, "Design Research Quarterly Volume 2 Issue 1" (2007). Design Research Quarterly. 2. https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/design-research-quarterly/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the DRS Archive at DRS Digital Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Design Research Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DRS Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V.2:1 January 2007 www.designresearchsociety.org Design Research Society ISSN 1752-8445 Paolo Astrade Wonderground 2007 Plenary: Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa Perspectives on Table of Contents: 3 Forty Years of Design Research Design Nigel Cross 7 Simplicity Per Mollerup 16 Design Thinking Nigel Cross Charles Owen Forty Years of 28 Wonderground and Forward Design Research p. 3 Chris Rust 29 Seven New Fellows of the Design Research Society ICM Report: 30 BRAZIL: 7th P&D Brazilian Conference on Research and Development in Design Daniela Büchler Per Mollerup Design Conference Calendar: Simplicity p. 7 31 Upcoming Events Worldwide Artemis Yagou Call for Papers: 6 Emerging Trends in Design Research 2007 IASDR conference, Hong Kong 15 Shaping the Future? 9th International Conference on Engi- neering and Product Design Ed. Creative Makers Newcastle upon Tyne UK Domain Invention Charles Owen 32 Livenarch Contextualism in Architecture Design Thinking: Trabzon Turkey Notes on Its Analysis Synthesis Nature and Use p . -

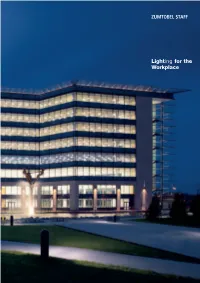

Lighting for the Workplace

Lighting for the Workplace AWB_Workplace_Q_Produktb_UK.qxd 02.05.2005 10:35 Uhr Seite 3 CONTENTS 3 Foreword by Paul Morrell, 4–5 President of the British Council for Offices INTRODUCTION 6–7 The Changing Corporate Perspective 6–7 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE 8–51 Lighting Research versus the Codes 10–11 – The Lessons of Lighting Research 12–15 – Current Guidance and its Limitations 16–23 Key Issues in Workplace Lighting 24–29 Natural Light, Active Light & Balanced Light 30–37 Further Considerations in Workplace Lighting 38–47 Lighting Techniques – Comparing the Options 48–51 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – APPLICATION AREAS 52–97 Open Plan Offices 56–67 Cellular Offices 68–71 Dealer Rooms 72–75 Control Rooms 76–79 Call Centres 80–83 Communication Areas/Meeting Rooms 84–87 Break-Out Zones 88–91 Storage 92–93 Common Parts 94–97 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – LIGHTING DESIGN 98–135 Product Selector 100–133 Advisory Services 134–135 References & Useful Websites 135 IMPRINT Publisher: Zumtobel Staff GmbH, Dornbirn/A Design: Marketing Communication Reprints, even in part, require the permission of the publishers © 2005 Zumtobel Staff GmbH, Dornbirn/A Paul Morrell President of the British Council for Offices (BCO) London aims to continue being Europe’s leading financial centre and will need more, higher quality office space in the future (photo: Piper’s model of the future City of London, shown at MIPIM 2005) FOREWORD 5 The UK office market, in particular in London, is changing, driven by a number of long-term trends in international banking and finance. Informed forecasts, such as the recent Radley Report*, point, firstly, to a shift towards our capital city, at the expense of Paris and Frankfurt, as Europe’s leading financial centre, with a commensurate pressure on office space.