Mao's American Strategy and the Korean War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surprise, Security, and the American Experience Jan Van Tol

Naval War College Review Volume 58 Article 11 Number 4 Autumn 2005 Surprise, Security, and the American Experience Jan van Tol John Lewis Gaddis Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation van Tol, Jan and Gaddis, John Lewis (2005) "Surprise, Security, and the American Experience," Naval War College Review: Vol. 58 : No. 4 , Article 11. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol58/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen van Tol and Gaddis: Surprise, Security, and the American Experience BOOK REVIEWS HOW COMFORTABLE WILL OUR DESCENDENTS BE WITH THE CHOICES WE’VE MADE TODAY? Gaddis, John Lewis. Surprise, Security, and the American Experience. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 2004. 150pp. $18.95 John Lewis Gaddis is the Robert A. U.S. history, American assumptions Lovell Professor of History at Yale Uni- about national security were shattered versity and one of the preeminent his- by surprise attack, and each time U.S. torians of American, particularly Cold grand strategy profoundly changed as a War, security policy. Surprise, Security, result. and the American Experience is based on After the British attack on Washington, a series of lectures given by the author D.C., in 1814, John Quincy Adams as in 2002 addressing the implications for secretary of state articulated three prin- American security after the 11 Septem- ciples to secure the American homeland ber attacks. -

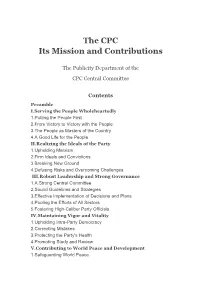

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions The Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee Contents Preamble I.Serving the People Wholeheartedly 1.Putting the People First 2.From Victory to Victory with the People 3.The People as Masters of the Country 4.A Good Life for the People II.Realizing the Ideals of the Party 1.Upholding Marxism 2.Firm Ideals and Convictions 3.Breaking New Ground 4.Defusing Risks and Overcoming Challenges III.Robust Leadership and Strong Governance 1.A Strong Central Committee 2.Sound Guidelines and Strategies 3.Effective Implementation of Decisions and Plans 4.Pooling the Efforts of All Sectors 5.Fostering High-Caliber Party Officials IV.Maintaining Vigor and Vitality 1.Upholding Intra-Party Democracy 2.Correcting Mistakes 3.Protecting the Party's Health 4.Promoting Study and Review V.Contributing to World Peace and Development 1.Safeguarding World Peace 2.Pursuing Common Development 3.Following the Path of Peaceful Development 4.Building a Global Community of Shared Future Conclusion Preamble The Communist Party of China (CPC), founded in 1921, has just celebrated its centenary. These hundred years have been a period of dramatic change – enormous productive forces unleashed, social transformation unprecedented in scale, and huge advances in human civilization. On the other hand, humanity has been afflicted by devastating wars and suffering. These hundred years have also witnessed profound and transformative change in China. And it is the CPC that has made this change possible. The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history dating back more than 5,000 years, China has made an indelible contribution to human civilization. -

Vol.9 No.4 WINTER 2016 겨울

겨울 Vol.9 No.4 WINTER 2016 겨울 WINTER 2016 Vol.9 No.4 겨울 WINTER 2016 Vol.9 ISSN 2005-0151 OnOn the the Cover Cover Lovers under the Moon is one of the 30 works found in Hyewon jeonsincheop, an album of paintings by the masterful Sin Yun-bok. It uses delicate brushwork and beautiful colors to portray a romantic mo- ment shared between a man and a wom- an. The poetic line in the center reads, “At the samgyeong hour when the light of the moon grows dim, they only know how they feel,” aptly conveying the heart-felt emo- tions of the lovers. winter Contents 03 04 04 Korean Heritage in Focus Exploration of Korean Heritage 30 Evening Heritage Promenade A Night at a Buddhist Mountain Temple Choi Sunu, Pioneer in Korean Aesthetics Jeongwol Daeboreum, the First Full Moon of the Year Tteok, a Defining Food for Seasonal Festivals 04 10 14 20 24 30 36 42 14 Korean Heritage for the World Cultural Heritage Administration Headlines 48 Sin Yun-bok and His Genre Paintings CHA News Soulful Painting on Ox Horn CHA Events Special Exhibition on the Women Divers of Jeju Korean Heritage in Focus 05 06 Cultural Heritage in the Evening Evening Heritage Promenade The 2016 Evening Heritage Promenade program opened local heritage sites to the public in the evening under seven selected themes: Nighttime Text & Photos by the Promotion Policy Division, Cultural Heritage Administration Views of Cultural Heritage, Night Stroll, History at Night, Paintings at Night, Performance at Night, Evening Snacks, and One Night at a Heritage Site. -

Comrade Mao Tse-Tung's Message of Greetings to 5Th Gongres$ of 4 Albanian Party of Labour

PE 46 November 11, 1966 il[ Comrade Mao Tse-tung's Message of Greetings to 5th Gongres$ of 4 Albanian Party of Labour A Choirmon Mao Reyiews Mighty Army of Cultural Revol ' ution .ru For 5th Time Nov. 11, 1966 PEKING REVEEW Vol- 9. No. 46 Published in Engtish, French, Sponish, Joponese ond Germon ditions t ARTICLES AND DOCUMENTS Comrode Moo Tse-tung's Messoge of Greetings to the Fifth Congress of the Albonion Porty of Lobour Choirmon Moo Reviews Mighty Army of the Culturql Revo- Iution for the 6th Time 6 Comrode Lin Pioo's Speech ot Peking Moss Rolly 10 C.omrode Lin Pioo Wdter lnscription for the 2Oth Anniversoqr ol the Norning ol the 'Jvho Ise-lung Locomotire" ll C.P.C. Ceiltrol Conrmit*ee Greets 25th Annirerory ol founding ol Albonion Pofi of Lobour 12 ' Congrotulotory Speech by Comrode Kong Sheng, Heod ol the Chinese Commu- nist Porty Delegrotion 13 . Fifth Congress of Albonion Pcrty ol Lobour Opem 16 ' More On Promoting the Contept of Jielangjun Bao editoriol 18 'Public" - Chino Will Remoin Red For Ever 21 Nurtured by Moo Tse-tung's Thought, Chino Grows Young 21 Itolion Morxist-Leninist Communist Porty Founded 22 Itolion Guorterly Vento DeLl' Est Wormly Proises Moo Tse-tung's Thought 22 Chino's Greot Culturol Revolution Tokes lts Ploce by the Side of the Poris Communs 23 Peking Welcomes Anti-Revisionist Fighters Returned From the Soviet Union 23 Choirmon Moo's Greot Concern for Anti-Revisionist Fighters 24 The Robber's Neck ond the People's Nooses - Observer 25 i Johnson's Bod Luck Renmin Riboo Commentotor 27 World's People Rejoice- Over Chino's Successful Guided Missile-Nucleor Weopon Test 28 Moo Tse-tung's Thought Shines For ond Wide 30 i, Deepest Love for Choir.mon Moo's Works ond Firmest Belief in Moo Tse-tung's- Thought Chong Kuei-mei 32 - fl $J THE WEEK Choirmon Moo Receives R,D. -

Mao and the 1956 Soviet Military

! ! !"#$"%&'()#$*+,$-"& .(#/&0122& & & & & 3%4&'()#$*+,$-"5&& & & & SHEN ZHIHUA & MAO AND THE 1956 SOVIET MILITARY INTERVENTION IN HUNGARY & & & & !"#$#%&''()*+,'#-./0)#%1) 2./)3456)7+%$&"#&%)8/9:'+;#:%)&%0);./)<:9#/;)=':>)?:+%;"#/-1)8/&>;#:%-)&%0) 8/*/">+--#:%-)) @0#;/0),()AB%:-)CD)8&#%/"E)F&;&'#%)<:G'&#) 2./)H%-;#;+;/)I:");./)7#-;:"():I);./)3456)7+%$&"#&%)8/9:'+;#:%E)7#-;:"#>&')J">.#9/-):I) ;./)7+%$&"#&%)<;&;/)</>+"#;(E)=+0&*/-;E)KLLM)) & 003Shenjo:Elrendezés 1 2007.11.11. 12:24 Oldal 24 SHEN ZHIHUA MAO AND THE 1956 SOVIET MILITARY INTERVENTION IN HUNGARY Sino-Soviet relations entered a honeymoon period when Khrushchev came to power. Friendship and cooperation were unimpaired despite worries on the part of Mao Zedong about some of Khrushchev’s actions at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). In fact, Khrushchev’s bold criticism of Stalin suited Mao Zedong because it relieved some pressure on him. Generally speaking, the guiding principles of the 20th Congress of the CPSU were identical with those of the 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP),1 to whose views 24 Moscow attached great importance at the time. Pravda went so far as to translate into Russian and reprint a CCP article entitled “On the historical experience of proletarian dictatorship”, which was also issued as a pamphlet in Russian in 200 000 copies, for study by the whole party.2 When another CCP article, “More on the historical experience of proletarian dictatorship”, was published, Soviet radio used its star announcer -

H-Diplo Essay 267- Shen Zhihua on Learning the Scholar's Craft

H-Diplo H-Diplo Essay 267- Shen Zhihua on Learning the Scholar’s Craft: Reflections of Historians and International Relations Scholars Discussion published by George Fujii on Tuesday, September 15, 2020 H-Diplo Essay 267 Essay Series on Learning the Scholar’s Craft: Reflections of Historians and International Relations Scholars 15 September 2020 The Journey of Scholarship https://hdiplo.org/to/E267 Series Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Commissioning Editors: Sergey Radchenko and Yafeng Xia Translated for H-Diplo by Yafeng Xia Essay by Shen Zhihua, East China Normal University I turned seventy on April 20, 2020. There is an old saying in China: “A man seldom lives to be seventy years old.” You can’t help but sigh helplessly. It is not uncommon that old age clouds your memory. Perhaps, too, it is still too early to pass the final judgment on me. But when looking back, many things come vividly to my mind. And I frequently reflect on the road I took to become a scholar. Without exaggeration, I was successful in my youth. I am the same age as New China. My parents went to Yan’an in 1936-38, studied at the Anti-Japanese University[1] and joined the Eighth Route Army. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, they were both assigned to work at the Ministry of Public Security. I grew up within the compound of the Ministry of Public Security, which was diagonally opposite of Tiananmen Square at the time. As a descendant of revolution, I was very comfortable from an early age. -

Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide

08 Investment.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 14/9/16 12:21 pm Page 81 Week in China China’s Tycoons Investment Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide Oceanwide Holdings, its Shenzhen-listed property unit, had a total asset value of Rmb118 billion in 2015. Hurun’s China Rich List He is the key ranked Lu as China’s 8th richest man in 2015 investor behind with a net worth of Rmb83 billlion. Minsheng Bank and Legend Guanxi Holdings A long-term ally of Liu Chuanzhi, who is known as the ‘godfather of Chinese entrepreneurs’, Oceanwide acquired a 29% stake in Legend Holdings (the parent firm of Lenovo) in 2009 from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for Rmb2.7 billion. The transaction was symbolic as it marked the dismantling of Legend’s SOE status. Lu and Liu also collaborated to establish the exclusive Taishan Club in 1993, an unofficial association of entrepreneurs named after the most famous mountain in Shandong. Born in Shandong province in 1951, Lu In fact, according to NetEase Finance, it was graduated from the elite Shanghai university during the Taishan Club’s inaugural meeting – Fudan. His first job was as a technician with hosted by Lu in Shandong – that the idea of the Shandong Weifang Diesel Engine Factory. setting up a non-SOE bank was hatched and the proposal was thereafter sent to Zhu Getting started Rongji. The result was the establishment of Lu left the state sector to become an China Minsheng Bank in 1996. entrepreneur and set up China Oceanwide. Initially it focused on education and training, Minsheng takeover? but when the government initiated housing Oceanwide was one of the 59 private sector reform in 1988, Lu moved into real estate. -

War Responsibility of the Chinese Communist Party, the Ussr and Communism

WAR RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY, THE USSR AND COMMUNISM How the US became entangled in the Comintern’s master plan to communize Asia Ezaki Michio, Senior fellow, Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference) Shock waves from Venona files continue to reverberate The Venona files have unmasked more than a few Soviet spies who infiltrated the US government during the World War II era. With the disclosure of the transcripts, what has for decades been a suspicion is on the point of becoming a certainty: the Roosevelt administration was collaborating with the Soviet Union and the CCP (Chinese Communist Party). A retrospective debate is in progress, and with it a reexamination of the historical view of that period; both have accelerated rapidly in recent years. The term “Venona files” is used to describe code messages exchanged between Soviet spies in the US and Soviet Intelligence Headquarters that were intercepted and decrypted by US Signals Intelligence Service personnel. The NSA (National Security Agency) released the transcripts to the public in 1995. As more of these messages were disclosed and analyzed, they revealed evidence likely to prove conclusively that at least 200 Soviet spies (or sympathizers) worked for the US government as civil servants. Their members included Alger Hiss ① (hereinafter I shall place numbers after the names of influential individuals, and use boldface font to indicate communists or communist sympathizers).1 Suspicions that there were Soviet spies in the Roosevelt administration date back more than 60 years. In 1948 Time magazine editor Whittaker Chambers, testifying before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, accused Alger Hiss ① of spying for the USSR. -

Communism a Jewish Talmudic Concept Know Your Enemy

Communism A jewish Talmudic Concept Know Your Enemy By Willie Martin Preface Chapter One – The Beginning of Communism Began With The Illuminati Chapter Two – Communism, The Illuminati and Freemasonry Chapter Three – The Khazars of Russia Become Jews Chapter Four – Jewish Ritual Mirder Chapter Five – Jewish Hatred For Christians Rekindled Chapter Six – Socialism To Be Substituted For Communism Chapter Seven – Russia Is Still Controlled By The Jews Chapter Eight – America Must Not Allow Itself To Be Deceived Any Longer Chapter Nine – Communism Is Jewish – The United States of America Has Come Under Jewish Control Chapter Ten – Jews Take Control of The Roman Catholic Church Chapter Eleven – Origin of The Jews Chapter Twelve – Communism A Jewish Talmudic Concept Conclusion Bibliographie Notes Page | 1 Preface To prove the title is true, we must lay a little ground work, before we get to the meat of the situation. Paul told us: "...we have many things to say, and hard to be uttered, seeing ye {most Christians} are dull of hearing. For when the time ye ought to be teachers, ye have need that one teach you again which be the first principles of the oracles of God; And are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat. For everyone that useth milk is unskillful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat {the real truth of what is happening in the world today} belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil {are able to understand}." [1] There are many who look but do not see, listen but do not hear as God told us, that True Israel, the Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian, Celtic and kindred people were: "Son of man, thou dwellest in the midst of a rebellious house, which have eyes to see, and see not; they have ears to hear, and hear not: for they are a rebellious house." [2] They join the latest and current cliche or clique because it has the appeal of the hour. -

WIC Template 13/9/16 11:52 Am Page IFC1

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

BURTON I. KAUFMAN (Blacksburg, VA, USA)

BURTON I. KAUFMAN (Blacksburg, VA, USA) INTRODUCTION: THE WORLD REMAINS A DANGEROUS PLACE Most politica! analysts agree that the Cold War ended in 1989, when revolutions in Poland and Hungary quickly spread to other East Eu- ropean countries, toppling existing Communist regimes and shattering the Iron Curtain that had divided Eastern and Western Europe for almost forty-five years. Much of the credit for these developments has been given to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who promoted economic and political liberalization in the Soviet Union through his policies of pe;e- s,rolka and glasnost', restricted the use of Soviet military power to main- tain Soviet hegemonic control over Eastern Europe and sought new and fruitful openings to the West. In 1992, of course, these same liberal poli- cies led to the disintegration of the Soviet Union itself, following an un- successful coup against Gorbachev. In a fine history on the end of the Cold War, Washington Post re- porter Don Oberdorfer has also attributed considerable credit to Presi- dent Ronald Reagan. Believing when he took office in 1981 that the So- viet Union was an "evil empire" (the term he used in a 1983 speech), Reagan was nevertheless anxious to ease tensions between Washington and Moscow. Determined to strengthen America's military posture, he was unalterably committed to his.Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI or "Star Wars"), despite Gorbachev's equatty resolute opposition to it. Throughout most of Reagan's administration, in fact, SDI remained the major impedi- ment to a Soviet-American disarmament agreement. in the end, however, the Soviets realized they could not afford the costs of competing with the United States in the development of sophisticated and enormously expensive military technology.