Evaluation of the Impact of Food for Assets on Livelihood Resilience in Senegal (2005 – 2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport EV 2009 Cartes Rev-Mai 2011 Mb MF__Dsdsx

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ---------- MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES ---------- Cellule de Suivi du Programme de Lutte contre la Pauvreté (CSPLP) ---------- Projet d’Appui à la Stratégie de Réduction de la Pauvreté (PASRP) Avec l’appui de l’union européenne ENQUETE VILLAGES DE 2009 SUR L'ACCES AUX SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE Rapport final Dakar, Décembre 2009 SOMMAIRE I. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS _____________________________________________ 3 II. OBJECTIF GLOBAL DE L’ENQUETE VILLAGES __________________________________ 3 III. ORGANISATION ET METHODOLOGIE ________________________________________ 5 III.1 Rationalité ______________________________________________________________ 5 III.2 Stratégie ________________________________________________________________ 5 III.3 Budget et ressources humaines _____________________________________________ 7 III.4 Calendrier des activités ____________________________________________________ 7 III.5 Calcul des indices et classement des communautés rurales _______________________ 9 IV. Analyse des premiers résultats de l’enquête _______________________________ 10 V. ACCES ET EXISTENCE DES SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE _________________________ 11 VI. Accès et fonctionnalité des services sociaux de base ________________________ 14 VII. Disparités régionales et accès aux services sociaux de base __________________ 16 VII.1 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un lieu de commerce ___________________________ 16 VII.2 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un point d’eau potable _________________________ -

Information Bulletin Africa: Floods

Information bulletin Africa: Floods This bulletin is issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. It provides overview of the floods situation and key action taken by National Red Cross/ Red Crescent Societies with the support of IFRC and RC/RC Movement partners. The multi-country floods’ situation is rapidly evolving as it is published. The information would be updated as per the changing context. Background and the Red Cross and Red Crescent action While some countries in Africa are experiencing drought, others are facing devastating floods. The scale and scope of disaster risk, underlying vulnerabilities and complex socio-political and economic factors are unparalleled. Climate change and environmental degradation are exacerbating risk many times over. Recent forecasts suggest the flooding will continue to worsen over the coming weeks, likely to impact over one million people before this crisis is over. In most of the affected countries, the flooding is severe. Affected countries include: (1) Cameroon, (2) Central African Republic, (3) Côte d'Ivoire, (4) Ghana, (5) Kenya, (6) Mali (7) Mauritania, (8) Niger, (9) Nigeria, (10) Senegal (11) Sierra Leone, (12) South Sudan. In addition, six other countries have reported flooding situations, namely: Ethiopia, Somalia, Uganda, DRC, Tanzania and Sudan. The Movement has responded to 12 flood situations with Disaster Emergency Relief Fund (DREF) or Emergency Appeals. Additional DREFs and new Emergency Appeals are likely, particularly in South Sudan and Central African Republic. The active floods have affected over 421,000, of which 85,800 are, or will be, assisted by Movement DREF or Emergency Appeals. -

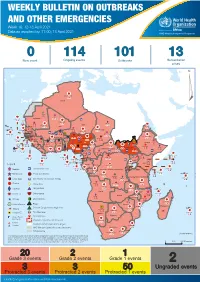

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

Z I G U I N C H O R 2 0

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi ------------------ MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN Z ------------------ AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE I ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ----------------- G Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Ziguinchor U I N C H O R 2 0 SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE REGIONALE 1 2016 6 Octobre 2019 COMITE DE DIRECTION Directeur Général BABACAR NDIR Directeur Général Adjoint ALLÉ NAR DIOP Conseiller à l’Action Régionale MAMADOU DIENG Président du CLV SECKENE SENE COMITE DE REDACTION Chef du Service Régional Jean Rodrigue MALOU Adjoint au Chef du Service Régional Alassane AW Le point focal du siège qui a aidé à la rédaction de Bintou Diack Ly la SESR COMITE DE LECTURE ET DE VALIDATION SECKENE SENE DIRECTION GENERALE AMADOU FALL DIOUF CPCCI SERGE MANEL DSDS IDRISSA DIAGNE ENSAE MAMADOU BALDE ENSAE OMAR SENE ENSAE AWA CISSOKHO FAYE DSDS MM. RAMLATOU DIALLO DSECN MANDY DANSOKHO ENSAE MAMADOU DIENG CAR NDEYE BINTA DIEME COLY DSDS MAMADOU AMOUZOU OPCV ADJIBOU OPPAH BARRY OPCV BINTOU DIACK LY DSECN MAMADOU BAH DMIS EL HADJI MALICK GUEYE DMIS ABDOULAYE TALL OPCV MOMATH CISSE CGP MAHMOUTH DIOUF DSDS MORY DIOUSS DSDS ATOUMANE FALL DSDS ALAIN FRANCOIS DIATTA DMIS SES de Ziguinchor, Ed. 2016 AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE Rocade Fann –Bel-air–Cerf-volant – Dakar Sénégal. B.P. 116 Dakar R.P. - Sénégal Téléphone (221) 33 869 21 39 - Fax (221) 33 824 36 15 Site web : www.ansd.sn ; Email: [email protected] Distribution : Division de la Documentation, de la Diffusion et des Relations avec les Usagers Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Ziguinchor Adresse : Tilene Complémentaire Tél : 33 991 12 58 B.P. -

Figure 4.1 Map of Dakar, Senegal...29

Public Disclosure Authorized Baseline and feasibility assessment for alternative cooking fuels in Senegal Public Disclosure Authorized May 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, MSN U11-1102 Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-458-7955 Fax: 202-522-2654 Website: http:// www.worldbank.org All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. Baseline and feasibility assessment for alternative cooking fuels in Senegal 2 Contents Acronyms and abbreviations ............................................................................................. 6 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. -

Cdm-Ar-Pdd) (Version 05)

CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM for A/R CDM project activities (CDM-AR-PDD) (VERSION 05) TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 2 SECTION B. Duration of the project activity / crediting period 19 SECTION C. Application of an approved baseline and monitoring methodology 20 SECTION D. Estimation of ex ante actual net GHG removals by sinks, leakage, and estimated amount of net anthropogenic GHG removals by sinks over the chosen crediting period 26 SECTION E. Monitoring plan 33 SECTION F. Environmental impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 43 SECTION G. Socio-economic impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 44 SECTION H. Stakeholders’ comments 45 ANNEX 1: CONTACT INFORMATION ON PARTICIPANTS IN THE PROPOSED A/R CDM PROJECT ACTIVITY 50 ANNEX 2: INFORMATION REGARDING PUBLIC FUNDING 51 ANNEX 3: BASELINE INFORMATION 51 ANNEX 4: MONITORING PLAN 51 ANNEX 5: COORDINATES OF PROJECT BOUNDARY 52 ANNEX 6: PHASES OF PROJECT´S CAMPAIGNS 78 ANNEX 7: SCHEDULE OF CINEMA-MEETINGS 81 ANNEX 8: STATEMENTS OF THE DNA 86 ANNEX 9: LETTER OF THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT REGARDING EIA 88 ANNEX 10: RARE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES 89 ANNEX 11: ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT PHASES 91 SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity A.1. Title of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> Title: Oceanium mangrove restoration project Version of the document: 01 Date of the document: November 10 2010. A.2. Description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> The proposed A/R CDM project activity plans to establish 1700 ha of mangrove plantations on currently degraded wetlands in the Sine Saloum and Casamance deltas, Senegal. -

Alice Joyce Hamer a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degre

TRADITION AND CHANGE: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF DIOLA WOMEN (SOUTHWEST SENEGAL) IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Alice Joyce Hamer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfullment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan c'7 1983 Doctoral Committee: Professor Louise A. Tilly, Co-chair Professor Godfrey N. Uzoigwe, Co-Chair -Assistant Professor Hemalata Dandekar Professor Thomas Holt women in Dnv10rnlomt .... f.-0 1-; .- i i+, on . S•, -.----------------- ---------------------- ---- WOMEN'S STUDIES PROGRAM THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 354 LORCH HALL ANN ARB R, MICHIGAN 48109 (313) 763-2047 August 31, 1983 Ms. Debbie Purcell Office of Women in Development Room 3534 New State Agency of International Development Washington, D.C. 20523 Dear Ms. Purcell, Yesterday I mailed a copy of my dissertation to you, and later realized that I neglected changirg the pages where the maps should be located. The copy in which you are hopefully in receipt was run off by a computer, which places a blank page in where maps belong to hold their place. I am enclosing the maps so that you can insert them. My apologies for any inconvenience that this may have caused' you. Sincerely, 1 i(L 11. Alice Hamer To my sister Faye, and to my mother and father who bore her ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Numerous people in both Africa and America were instrumental in making this dissertation possible. Among them were those in Senegal who helped to make my experience in Senegal an especially rich one. I cannot emphasize enough my gratitude to Professor Lucie Colvin who honored me by making me a part of her distinguished research team that studied migration in the Senegambia. -

Data Specifications

SECOND ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL BOUNDARIES DATA SPECIFICATIONS Version 2.0 Produced on June 2021 by: [email protected] SALB programme [email protected] Revision history Revision Revision date Comment Version 1.0 01 July 2017 Version 1.1 01 July 2018 Version 2.0 01 June 2021 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TERMINOLOGY 5 ACRONYMS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 DISCLAIMER AND TERMS 7 SECTION 1- GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS 7 1.1 DEFINITIONS AND ROLE 7 1.2 HIERARCHY TERMINOLOGY 8 1.3 NAMES 8 1.4 DATA SOURCE 9 1.5 COUNTRIES CODES 9 1.6 DATE FORMAT 9 SECTION 2 - CODING SYSTEM 9 2.1 OVERVIEW 9 2.2 CODING THE INITIAL LIST OF ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS AS OF JANUARY 2000 10 2.2.1 CODING THE FIRST SUBNATIONAL LEVEL 10 2.2.2 CODING THE SECOND SUBNATIONAL LEVEL 11 2.2.3 CODING UNITS PRESENTING THE SAME GEOGRAPHIC EXTENT AT THE 1st AND 2nd SUBNATIONAL LEVEL 12 2.2.4 CODING AREAS WITHOUT ADMINISTRATION 12 2.2.5 CODING AREAS UNDER NATIONAL ADMINISTRATION 13 2.2.6 CODING SECOND SUBNATIONAL LEVEL UNITS LOCATED ACROSS DIFFERENT FIRST LEVEL UNITS 13 2.3 CODING OF HISTORICAL CHANGES 15 2.3.1 SPLITING OR MERGING ADMINSTRATIVE UNIT 15 2.3.2 RENAMING ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS 17 2.3.3 ADDING A NEW ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE17 2.3.4 CHANGING THE ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT TYPE FOR A GIVEN ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL 18 2.3.5 REMOVING AN ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL 19 2.3.6 RE-INTRODUCING AN ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL 20 2.3.7 TERRITORIES WITH SPECIAL STATUS 21 3 SECTION 3 – HISTORICAL TABLES 22 3.1 OVERVIEW 22 3.2 CONTENT 22 3.3 FORMAT AND LAYOUT 23 SECTION 4 - GEOSPATIAL DATA 24 4.1 OVERVIEW 24 4.2 GEOMETRY TYPE -

Economic Growth Project

ECONOMIC GROWTH PROJECT CONTRACT 685-I-00-06-00005-00 TA SK ORDER 5 FY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OCTO BER 1, 2012 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 October 2013 This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of International Resources Group (IRG) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. ECONOMIC GROWTH PROJECT CONTRACT 685-I-00-06-00005-00 TASK ORDER 5 FY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2012 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 October 2013 Submitted by International Resources Group (IRG) DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government Economic Growth Project FY 2013 Annual Report i CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Highlights FY2013 ................................................................................................................................................. 3 FY2013 Feed the Future Indicator Overview .................................................................................................. -

Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous Knowledge Local Pathways to Global Development Marking Five Years of the World Bank Indigenous Knowledge for Development Program i © 2004 Knowledge and Learning Group Africa Region The World Bank IK Notes reports periodically on indigenous knowledge (IK) initiatives in Sub-Saharan Africa and occasionally on such initiatives outside the Region. It is published by the Africa Region’s Knowledge and Learning Group as part of an evolving IK partnership between the World Bank, communities, NGOs, development institutions, and multilateral organizations. For information, please e-mail: [email protected]. The Indigenous Knowledge for Development Program can be found on the web at http://worldbank.org/afr/ik/default.htm The views and opinions expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the World Bank or any of its affiliated organizations. iii Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ vii Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................ ix Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................................................ x Acronyms and Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................................