Essays on the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

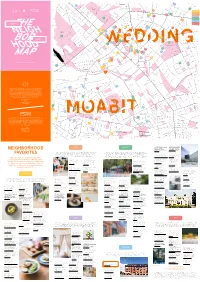

Neighborhood Favorites

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Markstraße Müllerstraße Brienzer Str. 45 Usambarastraße 73 Togostraße Soldiner Str. Schwyzer Str. Swakopmunder Str. Damarastraße Liverpooler Str. ENGLISCHES Koloniestraße 60 Gotenburger Str. Prinzenallee VIERTEL Str. Drontheimer A Dubliner Str. Biesentaler Str. A 29 Osloer Str. OSLOER STRASSE ! RESTAURANTS Armenische Str. Windhuker Str. REHBERGE Barfusstraße Glasgower Str. Stockholmer Str. 80 56 Wriezener Str. ! CAFÉS 15 93 Osloer Str. Freienwalder Str. Grüntaler Str. SCHILLERPARK 96 Petersallee 86 ! SHOPS Iranische Str. Schwedenstraße Lüderitzstraße BORNHOLMER Togostraße 63 Indische Str. Bornholmer Str. STRASSE Afrikanische Str. Edinburger Str. Str. Bellermannstraße ! ACTIVITIES Koloniestraße Koloniestraße Heinz-Galinski-Straße 25 Müllerstraße Exerzierstraße ! CULTURE Ungarnstraße Türkenstraße Klever Str. Oudenarder Str. ! BARS WEDDING Groniger Str. Seestraße Otawlstraße Sonderburger Str. B Uferstraße Spanheimstraße B 20 Gottschedstraße 23 Kongostraße 87 94 Eulerstraße 85 Gropiusstraße 97 Malplaquetstraße NAUENER PLATZ 81 Stettiner Str. Sansibarstraße Liebenwalder Str. Buttmannstraße 12 16 Thurneystraße 22 77 Grüntaler Str. VOLKSPARK Transvaalstraße Pankstraße Togostraße Turiner Str. 91 REHBERGE Lüderitzstraße SEESTRASSE 53 Bornemannstraße Bastienstraße Hochstädter Str. Schulstraße Zingster Str. Schönstedtstraße Heidebrinker Str. 1 95 Böttgerstraße Behmstraße Guineastraße 32 68 Amsterdamer Str. 13 Maxstraße Müllerstraße 2 GESUNDBRUNNEN 59 Utrechter Str. 37 MOABIT Kameruner Str. Prinz-Eugen-Straße Sambesistraße 99 Schererstraße Wiesenstraße Genter Str. 61 58 Antwerpener Str. Kösliner Str. Adolfstraße 6 Senegalstraße Dualastraße 76 41 Reinickendorfer Str. 54 Ramierstraße Lütticher Str. 51 Ugandastraße Nazarethkirchstraße C C Hochstraße C HUMBOLDTHAIN LEOPOLDPLATZ Tangastraße Seestraße 82 Brüsseler Str. Ruheplatzstraße Wiesenstraße Amrumer Str. 14 65 Graunstraße Pankstraße Antonstraße 90 Swinemünder Str. Dohnagestell Ostender Str. 83 30 Pasewalker Str. Pasewalker Str. HUMBOLDTHAIN Putbusser Str. Genter Str. 8 55 89 98 Rügener Str. -

Für Mensch Und Natur Inhalt

Jahresbericht 2011 Für Mensch und Natur inhalt impressum................................................................................... 2 Geschäftsführender Vorstand 2011 1. Vorsitzender: Torsten hauschild Vorwort .........................................................................................3 2. Vorsitzender: Rainer altenkamp NabU Wegmarken .......................................................................4 schatzmeister: Wolfgang steffenhagen beisitzer: Andreas höhne, Dr. Melanie v. Orlow, NabU berlin in Zahlen ..................................................................5 Thomas tennhardt NaJU sprecher: André Müller artenschutz und biotoppflege ......................................................6 Geschäftsführerin: Anja sorges impressum • Lebensqualität Wasser ..........................................................8 Laut satzung kann gemäß § 12 „der Geschäftsführende Vorstand Redaktion & Layout • artenschutz am Gebäude .....................................................8 carmen baden (...) die Grundsätze der arbeit des Landesverbandes aufstellen und fortschreiben.“ Der Geschäftsführende Vorstand wird von der Druck • schwingen, Federkleider und schillernde Gefieder ............10 brandenburgische Universitätsdruckerei Mitgliederversammlung für die Dauer von vier Jahren gewählt. und Verlagsgesellschaft Potsdam mbh, regional bis international ...........................................................11 Neuwahlen zum Vorstand erfolgen satzungsgemäß im Jahr 2014. gedruckt auf 100% recyclingpapier Natur erleben -

I Research Text

I Research Text Summer in Berlin Summer in Berlin means more summer! Berlin, June 2017 Summer in Berlin is always special. Because Berlin has a lot of summer to offer every year. With the first warm days, the capital kicks off its festival summer, classical summer, theatre summer, culinary summer, and summer at the lakes. Berlin is celebrating summer in the green with an extra highlight as it hosts the IGA International Garden Exhibition for the first time this year. In short, Berlin has the perfect summer for everyone, whether dancing in the streets at festivals, picnicking in the city's parks and gardens, strolls along the water's edge on the Spree or any of the city's dozens of lakes, taking in a bit of culture on outdoor stages, indulging in culinary treats and street food fare, or partying through the night in the city's beach bars and clubs. The main thing for everyone is heading outside to enjoy summer in Berlin. sommer.visitBerlin.de Berlin's Summer of Festivals With the first rays of sunshine, Berlin literally dances its way into a summer season full of celebration. Every year, on the 1st of May, the Myfest takes place in Berlin's Kreuzberg district, followed by the annual Carnival of Cultures over Pentecost/Whitsun weekend (2017: 2–5 June) that brings in more than a million people to the city. The carnival parade on Sunday is a true celebration of Berlin's cultural diversity with spectacular costumes and rhythmic dances worn by people representing more than 80 nations around the world. -

Senatsverwaltung Für Inneres Und Sport Berlin, 05. September 2019 IV a 2 – 07151-2021 - 9(0)223-2941 [email protected]

Senatsverwaltung für Inneres und Sport Berlin, 05. September 2019 IV A 2 – 07151-2021 - 9(0)223-2941 [email protected] An die Vorsitzende des Ausschusses für Sport über die Vorsitzende des Hauptausschusses über den Präsidenten des Abgeordnetenhauses über Senatskanzlei – G Sen – 35. Sitzung des Ausschusses für Sport vom 16. August 2019 Der Sportausschuss hat in seiner oben bezeichneten Sitzung zum Tagesordnungspunkt 2 die sich aus der Anlage ergebenden Berichtsaufträge beschlossen. Hierzu wird berichtet: siehe nachfolgende Sammelvorlage, Seiten 2 bis 90, zuzüglich der Anlagen (24 Seiten) Die Nummerierung der Berichtsaufträge richtet sich nach den lfd. Nummern der zur 1. Lesung vor- gelegten Synopse der Berichtsaufträge. Zum Berichtsauftrag lfd. Nr. 75 (AfD, Personalkosten BBB) ergeht ein gesonderter Bericht. Die Beantwortung der Berichtsaufträge zu den Berliner Bäder-Betrieben erfolgte unter Beteiligung der BBB. Die Beantwortung der Berichtsaufträge zu den Baumaßnahmen erfolgte unter Beteiligung der Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen. Der Landessportbund Berlin wurde in die Beantwortung der Fragen zu von ihm umzusetzenden Förderprogrammen ebenfalls beteiligt. Die Berichtsaufträge bitte ich mit dieser Sammelvorlage als erledigt anzusehen. In Vertretung Sabine Smentek Senatsverwaltung für Inneres und Sport Seite 1 von 90 Inhalt: 05 10 – 05 12 Senatsverwaltung für Inneres und Sport - Übergreifende Berichtsaufträge im Bereich Sport - ......................5 1 Gesamtkonzept zur Integration und Partizipation Geflüchteter -

Ecke Müllerstraße Zeitung Für Das »Aktive Zentrum« Und Sanierungsgebiet Müllerstraße

nr. 3 – juli/august 2019 ecke müllerstraße Zeitung für das »Aktive Zentrum« und Sanierungsgebiet Müllerstraße. Erscheint sechsmal im Jahr kostenlos. Herausgeber: Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin, Stadtentwicklungsamt, Fachbereich Stadtplanung Ch. Eckelt Eröffnung des neu gestalteten Max-Josef-Metzger-Platzes: Seiten 4/5 2 ——ECKE MÜLLERSTRASSE ECKE MÜLLERSTRASSE—— 3 IHR KIEZMOMENT Kopf steinpflaster der Ostender Straße oder den viel zu en- — — — ————————————————————— gen Radweg der verkehrsreichen Luxemburger Straße um- INHALT Alkoholkonsum und gehen. Im Verkehrskonzept für den Brüsseler Kiez, das im Jahr 2017 unter reger Bürgerbeteiligung erarbeitet wurde, Seite 3 Platzordnung für den Platz am Elise-und- wird sogar vorgeschlagen, auf dem Elise-und-Otto-Ham- Otto-Hampel-Weg Fahrradfahren verboten pel-Weg eine bezirkliche Radroute einzurichten. Man darf Seiten 4/5 Beweg dich Max! Der neue Max- Bezirksamt beschließt »Platzordnung also getrost erwarten, dass kaum ein Fahrradfahrer sich an Josef-Metzger Platz die Platzordnung halten wird: Die wird dann auch in ihren Müllerstraße 147, 149« anderen Inhalten obsolet. cs Seite 6 AG Verkehr des Runden Tisches Sprengel- kiez fordert Verkehrsberuhigung Seite 7 »Gott wohnt im Wedding« – eine Buch- ———————————————— DOKUMENTATION rezension Ch. Eckelt Seiten 8/9 Bürgerbefragung zum künftigen Weddingplatz Platzordnung Seite 10 Neues zu himmelbeet und Maxplatz Aus dem Bezirk Mitte: Müllerstraße 147, 149 • Seite 11 Überfülltes Bürgeramt Wir möchten, dass sich alle unsere Besucher/innen auf dem • Seite 12 Wie wird die Pflege der Grünanlagen Platz sicher und wohlfühlen. Um allen Besucher/innen den finanziert? Aufenthalt auf dem Platz so angenehm wie möglich zu gestal- • Seite 13 Neuer Drogenkonsumraum? ten, wurde diese Platzordnung erlassen. • Seite 14 Bezirksnachrichten § 1 Geltungsbereich Dieses Foto »Goethepark links hinein Schotterwege« schickte unser Seite 15 Gebietsplan und Adressen Diese Platzordnung findet Anwendung auf allen öffentlich Leser Rolff Zlatar. -

Things to Do in Berlin – a List of Options 19Th of June (Wednesday

Things to do in Berlin – A List of Options Dear all, in preparation for the International Staff Week, we have composed an extensive list of activities or excursions you could participate in during your stay in Berlin. We hope we have managed to include something for the likes of everyone, however if you are not particularly interested in any of the things listed there are tons of other options out there. We recommend having a look at the following websites for further suggestions: https://www.berlin.de/en/ https://www.top10berlin.de/en We hope you will have a wonderful stay in Berlin. Kind regards, ??? 19th of June (Wednesday) / Things you can always do: - Famous sights: Brandenburger Tor, Fernsehturm (Alexanderplatz), Schloss Charlottenburg, Reichstag, Potsdamer Platz, Schloss Sanssouci in Potsdam, East Side Gallery, Holocaust Memorial, Pfaueninsel, Topographie des Terrors - Free Berlin Tours: https://www.neweuropetours.eu/sandemans- tours/berlin/free-tour-of-berlin/ - City Tours via bus: https://city- sightseeing.com/en/3/berlin/45/hop-on-hop-off- berlin?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_s2es 9Pe4AIVgc13Ch1BxwBCEAAYASAAEgInWvD_BwE - City Tours via bike: https://www.fahrradtouren-berlin.com/en/ - Espresso-Concerts: https://www.konzerthaus.de/en/espresso- concerts - Selection of famous Museums (Museumspass Berlin buys admission to the permanent exhibits of about 50 museums for three consecutive days. It costs €24 (concession €12) and is sold at tourist offices and participating museums.): Pergamonmuseum, Neues Museum, -

Planung.Freiraum Hat Ein Räumliches Nutzungskonzept Entwickelt, Das Viele Unterschiedliche Nutzende Und Vielfaltige Nutzungen Berücksichtigt

********************************************************************************* [ about ] planung . freiraum 09|2016 inhalt ] ********************************************************************************* information büro projekte stadtraum + plätze projekte öffentliche + private gebäude projekte schulen projekte fördereinrichtungen projekte parkanlagen + großer maßstab projekte wettbewerbe projekte sonstige gender diversity beteiligungsprozesse möbel für den freiraum information veröffentlichungen information preise + auszeichnungen information preisgerichte information ausstellungen information vorträge information kontakt planung . freiraum information büro ] ********************************************************************************* Inhaberin Barbara Willecke ausgebildete Landschaftsgärtnerin Dipl.-Ing. Garten- und Landschaftsarchitektin BDLA Architektenkammer Berlin 08108 seit 1995 Berufenes Mitglied des Fachfrauenbeirats der Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt, Berlin Lehrauftrag Beuth Hochschule Berlin, "urbaner Raum und Gesellschaft" seit 2013 Standorte Berlin und Köln Leistungen und Inhalte nutzungsorientierte Planungen Planungen und Entwicklungen im Bestand moderierte Planungsprozesse Planungen mit Bürgerinnen - Bürgern und Betroffenen Interdisziplinäre Konzepte und Entwürfe zu Raum, Stadt, Landschaft und Garten integrative Projekte in sozialen Brennpunkten Kommunikative Planungsmethoden und Konzepte zu Raum, Raumskulpturen Vorträge und Workshops zu Raum, Raum-Aneignung, -Wahrnehmung, -Beeinflussung, - -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Hobbs, Mark (2010) Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2182/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930 Mark Hobbs BA (Hons), MA Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of History of Art Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2010 Abstract This thesis examines the urban topography of Berlin’s working-class districts, as seen in the art, architecture and other images produced in the city between 1924 and 1930. During the 1920s, Berlin flourished as centre of modern culture. Yet this flourishing did not exist exclusively amongst the intellectual elites that occupied the city centre and affluent western suburbs. It also extended into the proletarian districts to the north and east of the city. Within these areas existed a complex urban landscape that was rich with cultural tradition and artistic expression. This thesis seeks to redress the bias towards the centre of Berlin and its recognised cultural currents, by exploring the art and architecture found in the city’s working-class districts. -

Internationale Wochen Gegen Rassismus 13.–28 März 2021

Programm 2021 INTERNATIONALE WOCHEN GEGEN RASSISMUS 13.–28 MÄRZ 2021 1 »Solidarität.Grenzenlos.« 2021 #IWgR Impressum Herausgeber*in: Zusammen gegen Rassismus c/o Demokratie in der Mitte Fabrik Osloer Straße e.V. Osloer Straße 12 13359 Berlin Redaktion: Zusammen gegen Rassismus Die Text-/Bildrechte liegen bei den jeweiligen Fotograf*innen/Autor*innen. Bildnachweis: S.04: Foto von Tayo Awosusi-Onutor ©Kitty Kleist-Heinrich S.06: Foto von Yasmin Poesy ©Aysha Mustafa S.10: Foto von Ramona Reiser ©Markus Heine S.12: Foto: Centre Français de Berlin (CFB) ©Margot Tracq V.i.S.d.P.: Demokratie in der Mitte c/o Fabrik Osloer Straße e.V., Osloer Straße 12, 13359 Berlin »Solidarität.Grenzenlos.« 2021 #IWgR Zusammen gegen Rassismus ist ein Zusammenschluss von über 26 Bündnismitgliedern und zahlreichen Kooperationspar- tner*innen aus Moabit, Wedding und Gesundbrunnen, die seit 2017 die »Internationalen Wochen gegen Rassismus« in Berlin-Mitte gemeinsam gestalten. Auch in diesem Jahr beteiligen sich wieder viele Vereine, Organisationen und Initiativen mit ihren Veranstaltungen an den Aktionswochen und setzen ein kraftvolles Zeichen gegen Rassismus und Diskriminierung. In Workshops, Konzerten, Filmvorführungen, Lesungen, Begegnungs- und Diskussionsveranstaltungen wird die Vielfalt der Menschen und Themen deutlich, die den Bezirk Mitte ausmacht. Die inhaltliche Verantwortung für die Ausgestaltung der Veranstaltungen liegt bei den jeweiligen Veranstalter*innen. Alle Veranstaltungen sind kostenlos. Viel Spaß beim Lesen des Programmheftes und bei den Veranstaltungen -

UND INFRASTRUKTURUNTERSUCHUNG Im Sanierungsgebiet + Aktiven Zentrum Karl‐Marx‐Straße/Sonnenallee in Berlin‐Neukölln

Ergebnisbericht WOHN‐ UND INFRASTRUKTURUNTERSUCHUNG im Sanierungsgebiet + Aktiven Zentrum Karl‐Marx‐Straße/Sonnenallee in Berlin‐Neukölln Büro für Stadtplanung, ‐forschung und ‐erneuerung (PFE) August 2015 Sanierungsgebiet Neukölln – Karl‐Marx‐Straße/Sonnenallee Bezirk Neukölln von Berlin Ergebnisbericht WOHN‐ UND INFRASTRUKTURUNTERSUCHUNG im Sanierungsgebiet Karl‐Marx‐Straße/Sonnenallee in Berlin‐Neukölln Auftraggeber: Bezirksamt Neukölln von Berlin Abteilung Bauen, Natur und Bürgerdienste Stadtentwicklungsamt Fachbereich Stadtplanung Koordination: Oliver Türk Auftragnehmer: Büro für Stadtplanung, ‐forschung und ‐erneuerung Oranienplatz 5 ‐ 10999 Berlin Tel: 030/6141071 | Fax: 030/6141072 info@pfe‐berlin.de | www.pfe‐berlin.de Bearbeitet von: Hans‐Jürgen Hempel Olaf Gersmeier Michael Gade Daniel Klette Christoph Toschka August 2015 Luftbild Titelblatt: Geoportal Berlin / Orthophotos 2014 (DOP20RGB) ERGEBNISBERICHT: Wohn‐ und Infrastrukturuntersuchung im Sanierungsgebiet + Aktiven Zentrum Karl‐Marx‐Straße/Sonnenallee in Berlin‐Neukölln Inhalt EINLEITUNG 3 1.1 ANLASS UND ZIEL ..........................................................................................................................3 1.2 AUFGABENSTELLUNG .....................................................................................................................5 1.3 METHODIK ...................................................................................................................................6 2 SITUATIONSANALYSE 9 2.1 DEMOGRAFIE ...............................................................................................................................9 -

Berlin Ohne Geld

Daniel Wiechmann Berlin ohne Geld 101 großartige Dinge, die Du in Berlin kostenlos erleben kannst USCIR C M U I S X M A © des Titels »Berlin ohne Geld« (978-3-7423-0603-6) 2018 by riva Verlag, Münchner Verlagsgruppe GmbH, München Nähere Informationen unter: http://www.rivaverlag.de Inhalt Berlin ohne Geld erleben ....................................................................................................................................10 Berlin im Steckbrief .......................................................................................................................................................12 Abenteuer 1. Singe beim Mauerpark- Karaoke. .........................................................................................................13 10. Fordere in Clärchens Ballhaus jemandem zum Tanzen auf. ...............................26 18. Gehe in den Beelitz- Heilstätten auf Geisterjagd. .........................................................36 28. Schließe neue Bekanntschaften in einem Wasch salon. .........................................52 30. Bezwinge den Türsteher vom Berghain. ...................................................................................53 43. Erlebe die Berliner von ihrer mürrischen Seite in einem Bürgeramt deiner Wahl. ............................................................................................................................................................70 59. Performe auf der Bühne im Kreativhaus. ...................................................................................91 -

3 Zimmer Wohnung Im Zentrum Von Kreuzberg

0800 673 82 23 [email protected] +10 Bilder 285.000 € 77,9 m² 3 1 Kaufpreis Größe Zimmer Badezimmer Object-ID: 98VV93 TOP LAGE! 3 Zimmer Wohnung im Zentrum von Kreuzberg 10997 Berlin Wohnung zum Kauf Objektzustand Gepflegt Qualität der Ausstattung Normal Keller Vermietet Golden Star WunderAgent - Mein Partner in Vermietung und Verkauf Weitere Immobilien finden Sie auf www.wunderagent.de Beschreibung der Immobilie Immobiliendetails Immobilienart: Wohnung Immobilientyp: Etagenwohnung Etage: 1 von 5 Wohnfläche: 77,9 m² Objektzustand: Gepflegt Qualität der Ausstattung : Normal Baujahr: 1900 Zimmer: 3 Schlafzimmer: 2 Badezimmer: 1 Vermietet: Ja Kosten Sofort-Kaufpreis: 285.000,00 € 3.658,54 €/m² Kaufpreis: 285.000,00 € 3.658,54 €/m² Käuferprovision: 7,14% des Kaufpreises inkl. MwSt. Information zur Provision: Die vereinbarte Provision inklusive der gesetzlichen Mehrwertsteuer des vereinbarten Kaufpreises, ist verdient und fällig mit dem notariellen Vertragsabschluss. Diese ist zu leisten an WunderAgent GmbH, Helmerdingstraße 4, 10245 Berlin. Dies gilt auch sollte der Kaufpreis nachträglich gemindert oder rück abgewickelt werden. Vermietung Gesamt-Kaltmiete: 641,86 € +63% (8,24 €/m²) Gesamt-Kaltmiete: 394,17 € (5,06 €/m²) Wohnung: 394,17 € 2 [email protected] 0800 673 82 23 Details zum Energieausweis Datum der Erstellung: bis 30. April 2014 (EnEV 2009) Typ: Verbrauchsausweis Endenergieverbrauch: 198,0 Wesentlicher Energieträger: Gas Heizungsart: Zentralheizung 3 [email protected] 0800 673 82 23 Objektbeschreibung Dieses Gründerzeitgebäude zeichnet sich vor unterteilt in Vorderhaus, Seitenflügel und einem allem durch seine sehr gute Lage aus. Die Innenhof, welcher auch genügend Abstellplatz Wohnung befindet sich im 1.OG im für Fahrräder bietet. Vorderhaus. Lassen Sie sich verzaubern durch dieses Wichtig: Alle relevanten Information prächtige Altbauhaus, mit hohem emotionalen (vollständige Adresse, Bilder, Objektunterlagen, Wert.