Downloaded License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Kyrillische Schrift Für Den Computer

Hanna-Chris Gast Kyrillische Schrift für den Computer Benennung der Buchstaben, Vergleich der Transkriptionen in Bibliotheken und Standesämtern, Auflistung der Unicodes sowie Tastaturbelegung für Windows XP Inhalt Seite Vorwort ................................................................................................................................................ 2 1 Kyrillische Schriftzeichen mit Benennung................................................................................... 3 1.1 Die Buchstaben im Russischen mit Schreibschrift und Aussprache.................................. 3 1.2 Kyrillische Schriftzeichen anderer slawischer Sprachen.................................................... 9 1.3 Veraltete kyrillische Schriftzeichen .................................................................................... 10 1.4 Die gebräuchlichen Sonderzeichen ..................................................................................... 11 2 Transliterationen und Transkriptionen (Umschriften) .......................................................... 13 2.1 Begriffe zum Thema Transkription/Transliteration/Umschrift ...................................... 13 2.2 Normen und Vorschriften für Bibliotheken und Standesämter....................................... 15 2.3 Tabellarische Übersicht der Umschriften aus dem Russischen ....................................... 21 2.4 Transliterationen veralteter kyrillischer Buchstaben ....................................................... 25 2.5 Transliterationen bei anderen slawischen -

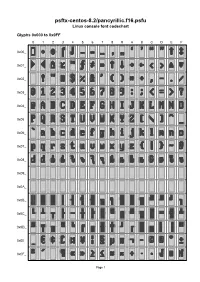

Psftx-Centos-8.2/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-centos-8.2/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW Filename: psftx-centos-8.2/pancyrillic.f16.psfu 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW PSF version: 1 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels Glyph count: 512 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING ANGLE QUOTATION MARK Unicode mappings 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, TRIANGLE U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE QUOTATION MARK 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK 0x00C U+201C LEFT DOUBLE -

ISO/IEC International Standard 10646-1

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3381 ISO/IEC 10646:2003/Amd.4:2008 (E) Information technology — Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) — AMENDMENT 4: Cham, Game Tiles, and other characters such as ISO/IEC 8824 and ISO/IEC 8825, the concept of Page 1, Clause 1 Scope implementation level may still be referenced as „Implementa- tion level 3‟. See annex N. In the note, update the Unicode Standard version from 5.0 to 5.1. Page 12, Sub-clause 16.1 Purpose and con- text of identification Page 1, Sub-clause 2.2 Conformance of in- formation interchange In first paragraph, remove „, the implementation level,‟. In second paragraph, remove „, and to an identified In second paragraph, remove „with an implementation implementation level chosen from clause 14‟. level‟. In fifth paragraph, remove „, the adopted implementa- Page 12, Sub-clause 16.2 Identification of tion level‟. UCS coded representation form with imple- mentation level Page 1, Sub-clause 2.3 Conformance of de- vices Rename sub-clause „Identification of UCS coded repre- sentation form‟. In second paragraph (after the note), remove „the adopted implementation level,‟. In first paragraph, remove „and an implementation level (see clause 14)‟. In fourth and fifth paragraph (b and c statements), re- move „and implementation level‟. Replace the 6-item list by the following 2-item list and note: Page 2, Clause 3 Normative references ESC 02/05 02/15 04/05 Update the reference to the Unicode Bidirectional Algo- UCS-2 rithm and the Unicode Normalization Forms as follows: ESC 02/05 02/15 04/06 Unicode Standard Annex, UAX#9, The Unicode Bidi- rectional Algorithm, Version 5.1.0, March 2008. -

Indigenous Peoples in the Russian Federation

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Johannes Rohr Report 18 IWGIA – 2014 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Copyright: IWGIA Author: Johannes Rohr Editor: Diana Vinding and Kathrin Wessendorf Proofreading: Elaine Bolton Cover design and layout: Jorge Monrás Cover photo: Sakhalin: Indigenous ceremony opposite to oil facilities. Photographer: Wolfgang Blümel Prepress and print: Electronic copy only Hurridocs Cip data Title: IWGIA Report 18: Indigenous Peoples in the Russian Federation Author: Johannes Rohr Editor: Diana Vinding and Kathrin Wessendorf Number of pages: 69 ISBN: 978-87-92786-49-4 Language: English Index: 1. Indigenous peoples – 2. Human rights Geographical area: Russian Federation Date of publication: 2014 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax: (45) 35 27 05 07 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.iwgia.org This report has been prepared and published with the financial support of the Foreign Ministry of Denmark through its Neighbourhood programme. CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................................................................................. 8 1 The indigenous peoples of the north ................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Matters of definition ......................................................................................................................................... -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

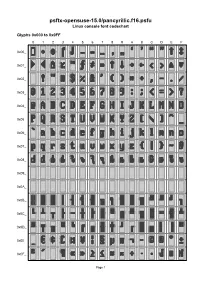

Psftx-Opensuse-15.0/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x017 U+221E INFINITY Filename: psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.p 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW sfu PSF version: 1 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph count: 512 Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING Unicode mappings ANGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT TRIANGLE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK -

MSR-4: Annotated Repertoire Tables, Non-CJK

Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4 Annotated Repertoire Tables, Non-CJK Integration Panel Date: 2019-01-25 How to read this file: This file shows all non-CJK characters that are included in the MSR-4 with a yellow background. The set of these code points matches the repertoire specified in the XML format of the MSR. Where present, annotations on individual code points indicate some or all of the languages a code point is used for. This file lists only those Unicode blocks containing non-CJK code points included in the MSR. Code points listed in this document, which are PVALID in IDNA2008 but excluded from the MSR for various reasons are shown with pinkish annotations indicating the primary rationale for excluding the code points, together with other information about usage background, where present. Code points shown with a white background are not PVALID in IDNA2008. Repertoire corresponding to the CJK Unified Ideographs: Main (4E00-9FFF), Extension-A (3400-4DBF), Extension B (20000- 2A6DF), and Hangul Syllables (AC00-D7A3) are included in separate files. For links to these files see "Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4: Overview and Rationale". How the repertoire was chosen: This file only provides a brief categorization of code points that are PVALID in IDNA2008 but excluded from the MSR. For a complete discussion of the principles and guidelines followed by the Integration Panel in creating the MSR, as well as links to the other files, please see “Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4: Overview and Rationale”. Brief description of exclusion -

Strategic Priorities and Forms of the Applying Ethnopolitics in the Arctic Areas of the Russian Federation © Flera Kh

Arctic and North. 2019. No. 34 110 UDC 94:[323.1+316.42](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2019.34.133 Strategic priorities and forms of the applying ethnopolitics in the Arctic areas of the Russian Federation © Flera Kh. SOKOLOVA, Dr. Sci. (Hist.), Professor E-mail: [email protected] Northern (Arctic) federal university named after M.V. Lomonosov, Arkhangelsk, Russia © Oleg V. ZOLOTAREV, Dr. Sci. (Hist.), Professor E-mail: [email protected] Syktyvkar State University named after Pitirim Sorokin, Syktyvkar, Russia © Liubov A. MAKSIMOVA, Cand. Sci. (Hist.), Associated Professor E-mail: [email protected] Syktyvkar State University named after Pitirim Sorokin, Syktyvkar, Russia © Igor V. SIBIRYAKOV, Dr. Sci. (Hist.), Professor E-mail: [email protected] South Ural State University (National Research University), Chelyabinsk, Russia Abstract. The article is dealing with the process of evolution of strategic priorities and practical forms of the realization of the ethnic policy in Russia on the example of the Arctic regions in the post-Soviet period. It is proved that the ethnopolitics of each Arctic region of the Russian Federation has its distinctive features, due to the complex of the reasons of its climatic, socio-economic, political and cultural nature. The differ- entiation of regional, national practices was more clearly manifested in the 1990s when in the Arctic re- gions, as well as in the whole country, the processes of sovereignty and politicization of ethnicity were ob- served. With the normalization of relations between the Federal center and regions, the separation of powers between the center and the entities of the Russian Federation at the turn of XX-XXI centuries, the Arctic regions are starting to build their ethnonational policy according to the strategic vision of the center. -

N1744.Qxp Cyril

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N1744 1998-05-25 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Œåæäóíàðîäíàß îðãàíèçàöèß ïî ñòàíäàðòèçàöèè Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Additional Cyrillic characters for the UCS Source: Michael Everson Status: Working Document Date: 1998-05-25 This document proposes several Cyrillic characters for inclusion in the UCS, and discusses the rationale for their inclusion. Most of these characters derive from ISO/TC46/SC4 standard ISO 10754:1996. The first three characters proposed are shown in the ALA/LC Romanization Tables. The last ten characters proposed in N1590 circulated on 1997-06-09 are shown the code table here, but the proposal summary form for them is in N1590. The characters proposed to be added here are given below, with proposed code positions. The table is found on the next page, and the proposal summary form is appended thereafter. hex Name 050F CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL WITH MIDDLE 0487 CYRILLIC TEN THOUSANDS SIGN HOOK 0488 CYRILLIC HUNDRED THOUSANDS SIGN 0510 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER MORDVIN EL KA 0489 CYRILLIC MILLIONS SIGN 0511 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER MORDVIN EL KA 04C5 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER CHECHEN KA 0512 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER EN WITH MIDDLE 04C6 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHECHEN KA HOOK 04C9 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER CHUVASH NG 0513 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN WITH MIDDLE 04CA CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHUVASH NG HOOK 04CD CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER KOMI NG 0514 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER ER KA 04CE CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KOMI NG 0515 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER -

Book of Abstracts

Congressus Duodecimus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum, Oulu 2015 Book of Abstracts Edited by Harri Mantila Jari Sivonen Sisko Brunni Kaisa Leinonen Santeri Palviainen University of Oulu, 2015 Oulun yliopisto, 2015 Photographs: © Oulun kaupunki ja Oulun yliopisto ISBN: 978-952-62-0851-0 Juvenes Print This book of abstracts contains all the abstracts of CIFU XII presentations that were accepted. Chapter 1 includes the abstracts of the plenary presentations, chapter 2 the abstracts of the general session papers and chapter 3 the abstracts of the papers submitted to the symposia. The abstracts are presented in alphabetical order by authors' last names except the plenary abstracts, which are in the order of their presentation in the Congress. The abstracts are in English. Titles in the language of presentation are given in brackets. We have retained the transliteration of the names from Cyrillic to Latin script as it was in the original papers. Table of Contents 1 Plenary presentations 7 2 Section presentations 19 3 Symposia 199 Symp. 1. Change of Finnic languages in a multilinguistic environment .......................................................................... 201 Symp. 2. Multilingual practices and code-switching in Finno-Ugric communities .......................................................................... 215 Symp. 3. From spoken Baltic-Finnic vernaculars to their national standardizations and new literary languages – cancelled ...... 233 Symp. 4. The syntax of Samoyedic and Ob-Ugric languages ...... 233 Symp. 5. The development -

Institute of Language, Literature and History Komi Science Centre, Ural Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences

Federal Agency of ScientificO rganizations Institute of Language, Literature and History Komi Science Centre, Ural Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences Materials to ScientificC onferences Issue 36 I.L. Zherebtsov INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND HISTORY, KOMI SCIENCE CENTRE, URAL BRANCH, RAS: THE MAJOR RESULTS AND RESEARCH PROBLEMS (to 45 anniversary of establishment) Materials to XII International Finno-Ugric Congress (Oulu, Finland, August 17−21, 2015) Syktyvkar 2015 UDC 061.62:061.12 (063) Zherebtsov I.L. INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND HIS TORY, KOMI SCIENCE CENTRE, URAL BRANCH, RAS: the MAJOR RESULTS AND RESEARCH PROBLEMS (to 45 anniversary of establish ment). Materials to XII International Finno-Ugric Congress (Oulu, Finland, August 17−21, 2015). Syktyvkar: Institute of Language, Literature and History, Komi Science Centre, Ural Branch, RAS, 2015. 48 p. (Materials to ScientificC on- ferences. Issue 36). The work deals with the basic landmarks in the history of the Institute of Lan- guage, Literature and History, Komi Science Centre, Ural Branch, RAS, and the major results of researches of scientists in the field of language, literature, folklore, archeology, ethnography, Russian history, the major problems facing the scientists in the field of historical-philological sciences are noted. Scientific editor Cand. Sci. (History) A.D. Napalkov Editorial board I.L. Zherebtsov (chairman), I.O. Vaskul (deputy chairman), E.A. Tsypanov (depu- ty chairman), D.V. Milokhin (executive secretary), N.M. Ignatova, V.N. Kar- manov, Yu.A. Krasheninnikova, T.L. Kuznetsova, M.A. Matsuk, A.G. Musanov, D.A. Nesanelis, A.A. Popov, M.V. Taskaev, Yu.P. Shabaev Reviewers Dr. Sci.