Nonlethal Weapons and Capabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* * * Chemical Agent * * * Instructor's Manual

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. · --. -----;-:-.. -----:-~------ '~~~v:~r.·t..~ ._.,.. ~Q" .._L_~ •.• ~,,,,,.'.,J-· .. f.\...('.1..-":I- f1 tn\. ~ L. " .:,"."~ .. ,. • ~ \::'J\.,;;)\ rl~ lL/{PS-'1 J National Institute of Corrections Community Corrections Division * * * CHEMICAL AGENT * * * INSTRUCTOR'S MANUAL J. RICHARD FAULKNER, JR. CORRECTIONAL PROGRAM SPECIALIST NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF CORRECTIONS WASIHNGTON, DC 20534 202-307-3106 - ext.138 , ' • 146592 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In tl]!::; document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this "'"P 'J' ... material has been granted by Public Domain/NrC u.s. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). • Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system reqllires permission of the f ._kt owner, • . : . , u.s. Deparbnent of Justice • National mstimte of Corrections Wtulringttm, DC 20534 CHEMICAL AGENTS Dangerous conditions that are present in communities have raised the level of awareness of officers. In many jurisdictions, officers have demanded more training in self protection and the authority to carry lethal weapons. This concern is a real one and administrators are having to address issues of officer safety. The problem is not a simple one that can be solved with a new policy. Because this involves safety, in fact the very lives of staff, the matter is extremely serious. Training must be adopted to fit policy and not violate the goals, scope and mission of the agency. -

Negative Effects of the Use of Militarization Methods by the Police Force

Negative Effects of the Use of Militarization Methods by the Police Force Children and Adults Developmental Agency Programs, Inc. (CADAprograms) Commission on the Status of Women (CSW 65) United Nations Citizens to Abolish Domestic Apartheid, Inc 2901 Maryland Ave., P.O. Box 80 North Versailles, PA 15137 Phone: (412) 829-2711 Fax: (412) 829-2788 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cadaprograms.org Committee: Chemical Pollutant Eradication Council Chair: Dr. Janis C. Brooks 1 Presentation Outline Riot Control Agents Exposure to a riot control agent Health effects of exposure to riot control agents Treatment for riot control agents Protection and exposure to riot control agents Rubber Bullets The Americans With Disabilities Act And Law Enforcement Summary 2 Riot Control Agents Chloroacetophenone (CN) Chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile (CS) Other examples include: • Chloropicrin (PS), used as a fumigant (that is, a substance that uses fumes to disinfect an area); • Bromobenzylcyanide (CA); • Dibenzoxazepine (CR); and combinations of various agents. 3 Exposure to a riot control agent How you could be exposed to riot control agents. Fine droplets or particles Skin contact, Eye contact, or Breathing. How riot control agents work. The extent of poisoning Irritation of the area of contact (for example, eyes, skin, nose) The effects of exposure to a riot control agent 4 Health effects of exposure to riot control agents Symptoms immediately after exposure: Eyes: excessive tearing, burning, blurred vision, redness Nose: runny -

Dangerous Ambiguities: Regulation of Incapacitants and Riot Control Agents Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, OPCW Open Foru

Dangerous Ambiguities: Regulation of incapacitants and riot control agents under the Chemical Weapons Convention OPCW Open Forum Meeting, 2nd December 2009 Michael Crowley Project coordinator Bradford Nonlethal Weapon Research Project Chemical Weapons Convention • The Chemical Weapons Convention has proven to be an important defence against the horrors of chemical warfare, vitally important for protecting both military personnel and civilians alike. • Its core obligations are powerfully set out under Article 1, namely that States will never under any circumstances develop, stockpile, transfer or use chemical weapons. • However, certain ambiguities and limitations in the CWC control regime exist regarding regulation of riot control agents (RCAs) and incapacitants. If not addressed, they could endanger the stability of the Convention. Chemical Weapons Convention • Article 1: • Each State Party to this Convention undertakes never under any circumstances: •(a) To develop, produce, otherwise acquire, stockpile or retain chemical weapons, or transfer, directly or indirectly, chemical weapons to anyone; •(b) To use chemical weapons; • (c) To engage in any military preparations to use chemical weapons; •(d) To assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Convention. [Emphasis added]. CWC: Scope of coverage • The CWC is comprehensive in the toxic chemicals it regulates. • The definition of “toxic chemicals” under Article 2.2 includes chemicals that cause “temporary incapacitation”. • Under the Convention, the use of such “toxic chemicals” would be forbidden unless employed for “purposes not prohibited” and as long as the “types and quantities” are consistent with such purposes. • Among the “purposes not prohibited” is: “law enforcement including domestic riot control”. -

How to Demilitarize the Police

HOW TO DEMILITARIZE THE POLICE Bernard E. Harcourt Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law and Professor of Political Science at Columbia University September 2020 INTRODUCTION As peaceful protesters throughout the United wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Heavily weaponized States challenge the police killings of Black police officers in fully armored vehicles face-off women and men, they are confronted today with against mostly peaceful and unarmed civilian fully militarized police forces, equipped with M4 protesters. A new militarized police force has been rifles, sniper scopes, camouflage gear and helmets, deployed on Main Street USA, with images like tanks and mine-resistant ambush-protected these flooding our news feeds and social media: (MRAP) vehicles, and grenade launchers from the HOW TO DEFUND POLICE MILITARIZATION 2 This was on display on June 1 in Washington, This rhetoric is not unique to the Trump D.C., after President Donald Trump mobilized administration—it reflects the reality of modern the military police and a U.S. Army Black Hawk American policing in towns and cities across helicopter to control peaceful protesters, and the country. In 2014, responding to protests in deployed the 82nd Airborne Division to D.C. Then, Ferguson, Missouri, after the police killing of after tear-gassing and shooting peaceful protesters Michael Brown, SWAT officers, dressed in Marine with rubber bullets to clear a path for that now- pattern (MARPAT) camouflage moved next to infamous church photo-op, Trump marched with armored vehicles that looked like tanks with the Secretary of Defense and the highest-ranking mounted high-caliber guns. They frequently military general, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs pointed their Mega AR-15 Marksman and M4 of Staff Mark Milley, by his side—with General rifles, sniper Leupold long-range scopes, and Milley in full combat uniform. -

Memorandum on Protests, Policing, and COVID-19

M E M O R A N D U M August 31, 2020 To: Governors’ Offices From: National Governors Association Re: Memorandum on Protests, Policing, and COVID-19 Background In recent months, mass gatherings in the form of protests and demonstrations have occurred across the country. People have gathered to protest COVID-19 restrictions and closure orders as well as to call for law enforcement reform and racial justice.1 These events, alongside the COVID-19 public health crisis, have presented challenges for Governors and state public health and public safety officials. This memorandum provides strategies for Governors to reduce the risks of spreading COVID-19 during protests while protecting public safety. The body of the memo will provide: 1) an overview of a harm- reduction approach; 2) considerations for law enforcement strategies and tactics for protest policing; and 3) opportunities for Governors and senior state officials to minimize the spread of COVID-19. Harm Reduction Approach Governors’ offices can leverage lessons learned from previous public-health strategies to prevent other health issues during protests. A harm-reduction approach to protests can serve as an effective way to support protest activity by acknowledging the inherent risks and providing interventions to reduce these risks. Developed initially for adults with substance-use disorders, harm-reduction approaches generally accept continuing levels of risk in society as inevitable and seek to reduce adverse consequences.2 This perspective emphasizes the measurement of health, social, and economic outcomes, as opposed to the measurement of infection rates.3 Governors, at their discretion, may consider a harm-reduction approach to educate protesters about how to minimize risks during protests and modify their behavior to minimize the spread of COVID-19. -

Policing Protests

HARRY FRANK GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION Policing Protests Lessons from the Occupy Movement, Ferguson & Beyond: A Guide for Police Edward R. Maguire & Megan Oakley January 2020 42 West 54th Street New York, NY 10019 T 646.428.0971 www.hfg.org F 646.428.0981 Contents Acknowledgments 7 Executive Summary 9 Background and purpose Protest policing in the United States Basic concepts and principles Lessons learned 1. Background and Purpose 15 The Occupy movement The political and social context for protest policing Description of our research The stakes of protest policing Overview of this volume 2. Protest Policing in the United States 25 A brief history of protest policing in the United States Newer approaches in the era of globalization and terrorism Policing the Occupy movement Policing public order events after the Occupy movement Conclusion 3. Basic Concepts and Principles 39 Constitutional issues Understanding compliance and defiance Crowd psychology Conclusion 4. Lessons Learned 57 Education Facilitation Communication Differentiation Conclusion Authors 83 Acknowledgments This guide and the research that preceded it benefited from the help and support of many people and agencies. We are grateful to the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) of the U.S. Department of Justice for funding this project, which allowed us the opportunity to explore how American police agencies responded to the Occupy movement as well as other social movements and public order events. We thank Robert E. Chapman, Deputy Director of the COPS Office, for his many forms of support and assistance along the way. We are also grateful to The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation for its willingness to publish this guide. -

Riot Control Agents? Riot Control Or Incapacitating Agents, Sometimes Referred to As “Tear Gas”, Are a Group of Aerosol-Dispersed Chemical Compounds

Fact Sheet Riot Control Agents What are Riot Control Agents? Riot control or incapacitating agents, sometimes referred to as “tear gas”, are a group of aerosol-dispersed chemical compounds. These compounds temporarily make people unable to function by causing irritation to the eyes, mouth, throat, lungs and skin. Agents of these types can be dispersed from grenade, bomb, spray or canister and are commonly employed by police and military forces to regain control of crowds. Several different compounds are considered to be riot control agents. The most common compounds are known as: . Chloroacetophenone (CN or Mace7) . Chlorobenzyldenemalononitrile (CS or Tear Gas) For immediate assistance, call . Adamsite (irritating and vomiting agent that acts very the Poison Control Center similarly to CN and CS) Hotline: 1-800-222-1222. Other examples may include: . Oleoresin Capsicum (OC or Pepper Spray) . Chloropicrin (PS), which is also used as a fumigant (uses fumes to disinfect and area) . Bromobenzylcyanide (CA) . Dibenzoxazepine (CR) and combinations of various agents Exposure Riot control agents are used by law enforcement officials for crowd control, and are an effective weapon as they can disable an assailant. Some police SWAT teams have small grenades that contain rubber pellets and/or CS. Riot control agents are also widely used by individuals in the form of pepper spray for personal protection. If exposed, remove clothing, taking care to avoid skin contact with contaminated clothing, and rapidly wash the entire body with soap and water. If the eyes are burning or vision is blurred, rinse eyes out with plain water for 10 to 15 minutes, if wearing contacts remove and place with contaminated clothing. -

Crowd Dynamics in Public Order Ops

PUBLIC ORDER MANGEMENT Crowd Dynamics in Public Order OPs UN Peacekeeping PDT Standards for Formed Police Units 1st edition 2015 Public Order Management 1 Crowd Dynamics in PO OPs Background Successful outcomes that follow crowd control operations are based on proper planning, police officers and equipment employment, and on-the-ground decisions that are made by leaders and members of the FPU who are face-to-face with an unruly, or potentially unruly, crowd. In the recent past, there have been countless examples of civil disturbance situations around the world. The size and scope of these civil disturbances varied from small gatherings of people who were verbally protesting to full-blown riots that resulted in property destruction and violence against others. Over the past decade, law enforcement and professional experts have come to understand crowd dynamics. A better understanding of human behaviour and crowd dynamics has led to improved responses to crowd control. This module covers crowd dynamics and human behaviour, crowd types and tactics that are used within the various crowds, in order to give the commanders and operators a clear perception of the operational threats they may face with in the contest of a Crowd Control Operation. Aim To understand crowd dynamics and to know how actions or inactions carried out by Stability Police Forces in Public Order Operations can affects the potential for threats. Learning outcomes On completion of this module participants will be able to: - Describe the differences between various mass gatherings and the dangers they might present; - Be familiar with the potential development of mass gatherings; - Explain the common tactics used by protesters during a riot; - Describe the main behavioural theories; - Describe the factors that may affect the escalation of tension and outbreak of violence. -

GODIAC – Good Practice for Dialogue and Communication As Strategic Principles for Policing Political Manifestations in Europe

Recommendations for policing political manifestations in Europe GODIAC – Good practice for dialogue and communication as strategic principles for policing political manifestations in Europe With the fi nancial support from the Prevention of and Fight against Crime Programme of the European Union European Commission-Directorate- General Home Affairs. HOME/2009/ISEC/AG/182 The Booklet 2 The Booklet 3 Preface This booklet on recommendations for policing polit- The main target group for the booklet is police ical manifestations in Europe forms part of the ‘Good commanders, researchers and trainers that come in practice for dialogue and communication as strategic to contact with and police political manifestations. principles for policing political manifestations in Europe’ The project co-ordinator was the Swedish National (GODIAC) project. The booklet is one of four docu- Police Board. There were twenty partner organisa- ments produced by the GODIAC project. The other tions in twelve European countries. These consisted documents include a handbook on the the user-fo- of twelve police organisations and eight research/edu- cused peer-review evaluation method, a researcher cational organisations. anthology and ten individual fi eld study reports. The project ran between 1st August 2010 until 31st The purpose of the project was to identify and July 2013 with grateful fi nancial support provided by spread good practice in relation to dialogue and com- the Prevention and Fight against Crime Programme munication as strategic principles in managing and of the European Commission-Directorate-General preventing public disorder at political manifestations Home Affairs and the Swedish National Police Board. in order to uphold fundamental human rights and Our aim and aspiration is that the material pro- to increase public safety at these events in general. -

How to Protect Yourself When Covering a Protest

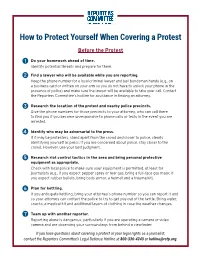

How to Protect Yourself When Covering a Protest Before the Protest 1 Do your homework ahead of time. Identify potential threats and prepare for them. 2 Find a lawyer who will be available while you are reporting. Keep the phone number for a local criminal lawyer and bail bondsman handy (e.g., on a business card or written on your arm so you do not have to unlock your phone in the presence of police) and make sure the lawyer will be available to take your call. Contact the Reporters Committee’s hotline for assistance in finding an attorney. 3 Research the location of the protest and nearby police precincts. Give the phone numbers for those precincts to your attorney, who can call there to find you if you become unresponsive to phone calls or texts in the event you are arrested. 4 Identify who may be adversarial to the press. If it may be protesters, stand apart from the crowd and closer to police, clearly identifying yourself as press. If you are concerned about police, stay closer to the crowd. However, use your best judgment. 5 Research riot control tactics in the area and bring personal protective equipment as appropriate. Check with local police to make sure your equipment is permitted, at least for journalists (e.g., if you expect pepper spray or tear gas, bring a full-face gas mask; if you expect rubber bullets, bring body armor, a helmet and a trauma kit). 6 Plan for kettling. If you anticipate kettling, bring your attorney’s phone number so you can report it and so your attorney can contact the police to try to get you out of the kettle. -

End Militarized Policing, Invest in Real Public Safety

POLICYBRIEFING End Militarized Policing, Invest in Real Public Safety Endless war and military violations of human rights are rooted in a specific mindset based on coercion, domination, and dehumanization. Excessive and violent policing drinks from the same source. Stopping systemic racism in police forces across the U.S. requires dealing with the problem at root and branch by enacting legal reforms, reversing the militarization of policing, and divesting funds from police forces prone to violence. Militarization at Home Increases Police Violence • Streets that were deserted during the early days of Coronavirus lockdowns now look like war zones. The DOD’s 1033 Program, which authorizes the Defense Department to send military equipment and weapons to local police departments, has been on full display as heavily armed cops and armored vehicles patrol the streets and crack down on protests over police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Oscar Grant, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, and far too many others to name. Julián Castro, former Secretary for Housing and Urban Development, explained best1 that “as long as our police arm up like a combat force, they’ll act like it.” • Studies have shown2 a “positive and statistically significant relationship between 1033 transfers and fatalities from officer-involved shootings ... [R]esearch suggests that officers with military hardware and mindsets will resort to violence more quickly and often.” • Georgetown Law professor Paul Butler, pointed out3 the difference between the militarized response to peaceful demonstrations about police brutality with protests against coronavirus restrictions earlier this year. “Unarmed people, many of whom are people of color, protest police brutality and are met with police brutality — flash grenades, tear gas, and rubber bullets. -

EXECUTIVE ORDER 13688 Federal Support for Local Law Enforcement Equipment Acquisition

Recommendations Pursuant to EXECUTIVE ORDER 13688 Federal Support for Local Law Enforcement Equipment Acquisition Law Enforcement Equipment Working Group MAY 2015 1 This page intentionally left blank 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... Page 4 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ Page 6 1. Executive Order 13688 ................................................................................................. Page 7 2. Stakeholders ................................................................................................................. Page 9 RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................................... Page 10 1. Equipment Lists ........................................................................................................ Page 11 2. Policies, Training, and Protocols for Controlled Equipment .................................... Page 17 3. Acquisition Process for Controlled Equipment ........................................................ Page 25 4. Transfer, Sale, Return, and Disposal of Controlled Equipment ............................... Page 29 5. Oversight, Compliance, and Implementation .......................................................... Page 31 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................