Recent Developments in Canadian Law: Bills of Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

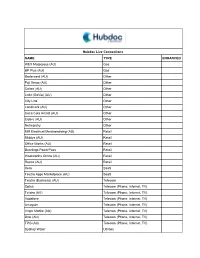

Live Canadian Bank and Supplier Connections NAME TYPE

Live Canadian Bank and Supplier Connections NAME TYPE ENHANCED Alterna Savings Banks and Credit Cards Amazon.ca Rewards Visa from Chase Banks and Credit Cards American Express (Canada) Banks and Credit Cards YES American Express Merchant Services (EUR) Banks and Credit Cards Assiniboine Credit Union Banks and Credit Cards ATB Financial (Business) Banks and Credit Cards YES ATB Financial (Personal) Banks and Credit Cards BMO Debit Card Banks and Credit Cards YES BMO Nesbitt Burns Banks and Credit Cards BMO Online Banking for Business Banks and Credit Cards Canadian Tire Options MasterCard Banks and Credit Cards Canadian Western Bank Banks and Credit Cards YES Capital One Mastercard (Canada) Banks and Credit Cards CHASE Bank Canada Banks and Credit Cards CIBC Banks and Credit Cards YES CIBC Wood Gundy Banks and Credit Cards Coast Capital Savings Banks and Credit Cards YES Costco Capital One Credit Card Banks and Credit Cards CUETS: Choice Rewards Mastercard Banks and Credit Cards Desjardins Business Banks and Credit Cards Desjardins VISA Banks and Credit Cards Envision Financial Banks and Credit Cards First National Financial Banks and Credit Cards Ford Credit (Canada) Banks and Credit Cards HBC Credit Card Banks and Credit Cards Home Depot Consumer Credit Card (Canada) Banks and Credit Cards Home Depot Revolving Commercial Charge Card (Canada) Banks and Credit Cards HSBC Bank Canada Banks and Credit Cards HSBC MasterCard Banks and Credit Cards Interior Savings Credit Union Banks and Credit Cards Island Savings Banks and Credit Cards MBNA -

Organizing for Effectiveness and Growth in Cooperative Financial Services a Focus on the Americas Foreword from the International Summit of Cooperatives

Financial Services ORGANIZING FOR EFFECTIVENESS AND GROWTH IN COOPERATIVE FINANCIAL SERVICES A FOCUS ON THE AMERICAS FOREWORD FROM THE INTERNATIONAL SUMMIT OF COOPERATIVES We would like to thank Oliver Wyman for their focus on cooperative financial services in the Americas. This pioneering report complements three previous Oliver Wyman studies focused on of the European cooperative banking sector, and its publication is timely as international stakeholders seek to understand better the organizational challenges, dynamics, and opportunities this sector represents. In contrast with Europe, where cooperative banking has a significant market share (and in some countries is the majority of the banking industry), cooperatives in the Americas typically account for a smaller proportion of both deposits and loans, and are systemically less important than their shareholder counterparts. Nevertheless, across the Americas, cooperative banks and credit unions have a significant – and, this report argues, growing – role to play given the natural synergy of cooperative values, member service, and community development. We welcome the fact that the study challenges the conventional wisdom of growth and organizational effectiveness in the sector and seeks to identify practices that will enhance the relevance and sustainability of the cooperative model. Ultimately, we believe these will help to ensure broad access to the financial system by all. SUZANNE GENDRON STÉPHANE BERTRAND Managing Vice President Executive Director Cooperation and Corporate Affairs International Summit of Cooperatives Desjardins ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Oliver Wyman acknowledges the industry executives and other stakeholders who contributed their perspectives and served as a sounding board in helping formulate our hypotheses throughout this project. Their willingness to share their views is a testament to the collaborative nature of the cooperative movement. -

A Guide to Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA)

A Guide to Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) Overview: Originally launched on April 9, 2020, CEBA is intended to support businesses by providing financing for their expenses that cannot be avoided or deferred as they take steps to safely navigate a period of shutdown, thereby helping to position businesses for successful relaunch when the economy reopens. This $55 billion program provides interest-free loans of up to $40,000 to small businesses and not-for-profits. Repaying the balance of the loan on or before December 31, 2022 will result in loan forgiveness of 25 percent (up to $10,000). As of June 26, 2020, businesses eligible for CEBA now include owner-operated small businesses that do not have a payroll, sole proprietors receiving business income directly, as well as family-owned corporations remunerating in the form of dividends rather than payroll. This means that more small businesses can access it. Applicants with $20,000 or less in payroll in 2019 will have to demonstrate having Eligible Non-Deferrable Expenses between Cdn.$40,000 and Cdn.$1,500,000 in 2020. Expenses are considered “Eligible Non-Deferrable Expenses” if they were already incurred in January and/or February 2020, or are due to a legal or contractual obligation as at March 1 and cannot be avoided or deferred beyond 2020 even during a period of shut down and depressed revenues as a result of COVID. CEBA is not intended to provide income support, or support for variable operating expenses to businesses. CEBA applicants agree that the government may conduct audits to confirm the nature of the expenses applicants use to establish their eligibility for CEBA, and acknowledge that inaccuracies may lead to legal consequences. -

Analysis of Canada's Largest Credit Unions

2012 Analysis of Canada’s Largest Credit Unions For the period ending December 31, 2012 Prepared by: Bob Leshchyshen, MBA, CFA October 2013 Analysis of Canada’s Largest Credit Unions in Canada Table of Contents Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Continued Strong Economic Growth in Canada…………………………………………………………………………………..6 Lending Activity – Residential Mortgages……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Housing Market in Canada………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………11 Lending Activity - Consumer Credit…………………………………………..………………………………………………..….17 Canadian Credit Union System……………………………………………………………………………………..…………….… 21 Membership………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….25 Consolidation of Credit Unions……………………………………………………………………………………………………..26 Branch Network…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….26 Assets…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….27 Deposits and Savingss…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….29 Loans……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..31 Overview of Credit Union System: Canada vs. United States……………………………………………………………..32 Credit Unions’ participation in the Brokerage Industry……………………………………………………………………….38 On-Line Deposit Taking Institutions…………………………………………………………………………………………………….51 Proposed Federal Credit Union Legislation………………………………………………………………………………………….56 Assets under Management………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….59 -

List of Financial Institutions Offering Locked-In Pension Products Issued: June 30, 2020

Superintendent’s List of Financial Institutions Offering Locked-In Pension Products Issued: June 30, 2020 This list is to be used for the purposes of sections 104-120, 105, 122-139, 141 and 162 of the Alberta Employment Pension Plans Regulation (154/2014, Consolidated up to 224/2014). The financial institutions that appear on this list, as indicated in bold typeface, have been acknowledged by the Superintendent to accept locked-in funds into the types of contracts indicated. The companies listed in regular typeface have been authorized by the financial institutions to accept locked-in funds on their behalf, and payments may be made directly to those listed agents. There may be institutions that have applied to appear on this list but whose application was still being processed at the time this list was updated. Please contact our office to verify the status of any financial institution with respect to this list. Questions may be directed to: Alberta Treasury Board and Finance Superintendent of Pensions #402, 9515 – 107 Street Edmonton, AB T5K 2C3 Phone: 780-427-8322 Email: [email protected] Website: http://pensions.alberta.ca SUPERINTENDENT’S LIST OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OFFERING LOCKED-IN PENSION PRODUCTS Classification: Protected A BANKS LIRA LIF Canadian Western Bank 21-Dec-15 CIBC (Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce) 1-Feb-07 23-Oct-07 Concentra Bank 20-Sep-06 20-Sep-06 Home Bank 6-Feb-18 HSBC Bank Canada 14-Sep-07 National Bank of Canada 11-Dec-07 Tangerine Bank 13-Nov-07 20-Jun-12 CREDIT UNIONS LIRA LIF BlueShore Financial -

JOHNSON-THESIS.Pdf

The Role of Governance in Balancing Conflicting Institutional Logics in a Canadian Credit Union A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Public Policy in the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kathleen J. Johnson Copyright Kathleen Joanne Johnson, December, 2015. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master’s degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. DISCLAIMER Reference in this thesis to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the University of Saskatchewan. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not state or reflect those of the University of Saskatchewan, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. -

Scholarship Booklet 2012-13

Page 1 MURDOCH MACKAY 2012 – 2013 Page 2 SCHOLARSHIPS 2012-2013 ATTENTION: Dates, amounts & availability are all subject to change & should be verified with a counsellor or the sponsoring organization. School selected awards (see Group A) require students to complete a GREEN application form and submit to Mrs. Morgan by May 14. To receive updated scholarship & volunteer information please see Ms Laporte to add your email onto her Scholarship distribution list. Group A – SCHOOL BASED SCHOLARSHIPS SCHOLARSHIP NAME AMOUNT DEADLINE Arthur Klingbell Math TBD Selected by Math Dept. Bob Land Memorial Scholarship $500 Selected by vocational teachers Casera Credit Union 2 @ $ 500 March (need to apply for) Chartwells Educational Award $500 School selected CUPE Local 4587 RETSD Clerical Scholarship $100 School selected Dr. & Mrs. M. MacKay – English $500 Selected by English Dept. Dr. & Mrs. Murdoch McKay Award $500 School selected Eddie Silver Fashion Award $1000 Selected by Fashion teachers Frances Kusner (Shandruk) 2@2500 School selected Fred & Mary Cornish $500 Selected by English Department Governor General’s Bronze Medal Medal School Selected Konrad Shandruk Family (renewable) 2 @ $1000 School Selected Kyle Johnson Memorial $1000 May (need to apply for) Lawrence Toet $150 School selected Life Touch $300 + gift School selected Linda Elke Memorial Staff Award $500 School selected Lindon Barrett Literary Award $500 School Selected Manitoba Aerospace Technical Skills Award $500 Selected by aerospace staff MJ (Eric) Kusner 2 @ $3000 School selected M.M.C.I. Clansmen Football Scholarship $750 March (need to apply for) M.M.C.I. Silver Celebration $ 500 May (need to apply for) Murdoch Motorsports Scholarship $1000 School selected Nan Shipley Writing Award $ 150 School Selected North American Lumber Award Gift certificate Selected by Building Construction staff Peter & Irene Tychonick Memorial $500 School selected Red River – Vickar Community Chev Olds $500 School Selected R.E.T.S.D. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX abusive behaviour, 150 senseless airline rules, 163–165 AC Jazz, 174 terms and conditions of carriage, 171, 172 AcceleRate Financial, 13 tickets and reservations, 171 account application form, 83–84, 86 weather and third party acts, 174 accountants, 89 airport terminals, 172 Aceto, Peter, 45 Alberta, 272 Achieva Financial, 13 allergies, 174 acts of God, 174 Alliance Data Systems Corp., 195 ADR Chambers Banking Ombuds Offi ce, 193 Alterna Bank, 12 Advantage Car & Truck Rentals, Amazon, 109, 213 198–199 Amazon Rewards Card, 29 advice, 82–84, 265–266 American Express, 210, 215 Aeroplan, 172, 194–197 American Express Canada, 270 age, 18, 19, 21–22 American Express Costco Platinum Cash Rebate agreements Card, 32 credit card agreements, 39–40 American Express Gold Rewards, 190 savings account agreement, 16–17 anger, 262 Aimia Inc., 195 anti-spyware soft ware, 219 Air Canada, 159, 160, 164, 170, 172, 174, antifraudcentre.ca, 216 176–177, 195, 196 antivirus soft ware, 219 Air Miles, 172, 194–197 Apple, 119, 120, 230, 232, 258 Air Transat, 164 AppleCare, 232 airlines, 156 askross.ca, 74 see also travel asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP), 92 bumping, 164–165, 171 authenticity, 162 cancellations, 173 authorized retailer, 214 cargo rates, 171 automatic banking machine (ABM), 15, 19, 29, code of conduct, 173 56, 58 complaints, 170–172,COPYRIGHTED 174 automatic MATERIAL renewals, 223–225 damaged luggage, 159–162 Avis Budget, 200 delays, 173 denied boarding, 171 baggage. See luggage fl ight disruptions, 171 baggage insurance policy, 169 Flight Rights, 173–175 bandwidth, 113 luggage issues. See luggage Bank of Montreal (BMO), 5, 18, 22 overbooking, 164–165, 173 Bank of Nova Scotia. -

Bare Trustee Agreements Approved Fund Managers As Ofapril 30, 2021 Fund Manager Region Type of Products Funds Covered by Agreement 1 1832 Asset Management L.P

Bare Trustee Agreements Approved Fund Managers as ofApril 30, 2021 Fund Manager Region Type of Products Funds covered by agreement 1 1832 Asset Management L.P. (Dynamic Funds) Canada Mutual Funds / Hedge Funds / LSF's Includes Deposit accounts 2 3IQ CORP. Canada Pooled Fund 3IQ Corp. 3 Aberdeen Global Services S.A. Overseas Mutual Fund Aberdeen Global Funds Aberdeen Global II Funds 4 Accilent Capital Management Inc. Canada Mutual Fund/Pooled Fund/Ltd. Partnership Capsure Hedged Oil and Gas Income & Growth Trust 5 Acker Finley Asset Management Inc. Canada Mutual Fund QSATM Funds 6 ACM Advisors Ltd. Canada Mortgage Investment Fund ACM Commercial Mortgage Fund 7 Addenda Capital Inc. Canada Pooled Fund Addenda Pooled Funds 8 ADS Canadian Bank Canada GIC's / Investment Savings Accounts 9 AGAWA Fund Management Inc. Canada Limited Partnership AGAWA Fund I Limited Partnership 10 AGF Investments Inc. Canada Mutual Fund / Pooled Fund Acuity Pooled funds AGF Pooled funds AGF Elements family of mutual funds Harmony family of mutual funds AGF family of mutual funds Acuity family of mutual funds 11 AHF Capital Partners Inc. Canada Mutual Fund/Hedge Fund/Pooled Fund AHF Credit Opportunities Fund - Series A, F and I 12 AIP Asset Management Inc. Canada Limited Partnership AIP Convertible Private Debt Fund LP 13 Aldergrove Credit Union Canada GIC's 14 Algonquin Capital Corporation Canada Limited Partnership 15 Alignvest Capital Management Inc. Canada Hedge Fund 16 Alignvest Investment Management Corporation Canada Pooled Fund 17 Alitis Investment Counsel Inc. Canada REIT Listing of Approved Fund Managers by Name Page 1 of 23 Fund Manager Region Type of Products Funds covered by agreement Alitis Private REIT Alitis Mortgage Plus Fund 18 AlphaFixe Capital Inc. -

Red Deer 1998 Dec H to Q

G 38 Grice—Hager 000107® TH.US Advertising Services Inc. 1997 GRICE BRIAN E Lawyr Grotto Wholes^e 347-8826 GULF CANADA RESOURCES UNITED 150 4919 59 St . ..342-2544 GROUP 4 C P S UNITED Prod Operations Ofc GUY'S PURE Fax Line 347-9895 219 3722 57Av 342-1499 201 4922 53 St 347-9779 WATER 342-0020 Grice E Brian 343-6992 GroupTherapy Centre MnFir4805 48Av.343-0337 24 HR EMERGENCY Grieb A 347-1062 STETTLER OPERATIONS Guy's Sand & Gravel 346-6144 Grieman Keith .....340-1640 GROUP 2 ARCHITECTURE (NoCharge) 1-800-662-7107 Gwartney L 32MunroCr 343-2829 24 Hr EmergefKy AD Departments Gwin Tom 343-9134 GRIER TIMOTHY 1 DR ENGINEERING INTERIOR ^ (NoCharge) 1-800-661-9525 Gwinner Harry & Anne 346-5671 Rimbey Gas Plant 843-7100 Gygi HL ISSDoranCr 346-1947 Optmtrst ParidandMM 342-5777 DESIGN 200 4706 48Av.. 340-2200 Gyori Brent 47DoranCr 341-5226 Fax Line 342-5784 Fax Line 346-6570 Gulka Myron 20BroughtonCr 346-0152 GraemeLeadbeaterM R A I C PenhoM 886-4494 Gullacher S&D 4413 4lAv 342-6343 Gyori Lome & Angela 346-1266 Grieve Grant ll2DowterSt 343-0433 Ron Mofrison 347-4606 Gullage Edwin 39 96HolmesSt 347-4936 Gyori M 302 5144 45Av 340-8336 Griffin Allen SSGrantSt 341-4503 Gulley Bruce 66DickensooCr. 340-0184 Gyori P T 309-1986 Griffin Andrea 346-8528 Grove BJ 309-2688 Gullickson John 342-1304 Gyori P T Faxline 340-8259 Griffin Bill 3912 55Av 343-0194 Grove Jeff 63 4250 54Av... 346-0642 GullifordRick 4 5829 60Av 347-6471 Gyori T 331 5344 76 St 340-3219 Grove KD 243-OverdownDr 347-3418 Gullion M 99Nob(eAve 343-0276 Gyori Tim 347-5157 GRIFFIN CONSTRUCTION -

Superintendent's Register / Registre Du Surintendant

SUPERINTENDENT'S REGISTER / REGISTRE DU SURINTENDANT September 22, 2021 / le 22 septembre, 2021 BANKS / BANQUES LIRA/CRI LIF/FRV BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA (See Bank of Nova Scotia Trust Co. (Scotiatrust)/Voir Societe de Fiducie Banque de Nouvelle-Ecosswe) X X CANADIAN IMPERIAL BANK OF COMMERCE (see CIBC Trust Corporation/Voir Compagnie Trust CIBC) X X CANADIAN WESTERN BANK X CONCENTRA BANK X X HSBC BANK CANADA X TANGERINE BANK X X NATIONAL BANK FINANCIAL GROUP X CREDIT UNIONS / CREDIT UNION ET CAISSES POPULAIRES LIRA/CRI LIF/FRV Central 1 Credit Union X X • Aldergrove Credit Union X X • Bulkley Valley Credit Union X X • CCEC Credit Union X X • Columbia Valley Credit Union X X • Compensation Employees Credit Union X X • Creston & District Credit Union X X • Cumberland & District Credit Union X X • East Kootenay Community Credit Union X X • Enderby & District Credit Union X X • First Credit Union X X • First West Credit Union X X • Fisgard Capital Corporation X X • Grand Forks District Savings Credit Union X X • Greater Vancouver Community Credit Union X X • Gulf and Fraser Credit Union X X • Heritage Credit Union X X • Integris Credit Union X X • Khalsa Credit Union X X • Kootenay Savings Credit Union X X • Ladysmith & District Credit Union X X • Lake View Credit Union X X • Mount Lehman Credit Union X X • Nelson & District Credit Union X X • Northern Savings Credit Union X X • North Peace Savings Credit Union X X • Osoyoos Credit Union X X • Revelstoke Credit Union X X • Salmon Arm Savings Credit Union X X Superintendent's Register / Registre du Surintendant 1 of 9 CREDIT UNIONS / CREDIT UNION ET CAISSES POPULAIRES (cont) LIRA/CRI LIF/FRV • Sharons Credit Union X X • Spruce Credit Union X X • Summerland & District Credit Union X X • Sunshine Coast Credit Union X X • Union Bay Credit Union X X • V.P. -

Hubdoc Live Connections NAME TYPE ENHANCED WEX Motorpass

Hubdoc Live Connections NAME TYPE ENHANCED WEX Motorpass (AU) Gas BP Plus (AU) Gas Bartercard (AU) Other Fuji Xerox (AU) Other Caltex (AU) Other Linkt (GoVia) (AU) Other City Link Other Landmark (AU) Other Coca Cola Amatil (AU) Other Elders (AU) Other Netregistry Other MM Electrical Merchandising (AU) Retail Middys (AU) Retail Office Works (AU) Retail Bunnings PowerPass Retail Woolworths Online (AU) Retail Reece (AU) Retail Xero SaaS Telstra Apps Marketplace (AU) SaaS Telstra (Business) (AU) Telecom Optus Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) Telstra (AU) Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) Vodafone Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) Amaysim Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) Virgin Mobile (AU) Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) iiNet (AU) Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) TPG (AU) Telecom (Phone, Internet, TV) Sydney Water Utilities AGL Energy Online (Business) Utilities Link Market Services (Portfolio Login) (AU) Utilities Sensis (AU) Utilities Energy Australia Utilities Synergy (AU) Utilities Origin Energy (AU) Utilities AGL Energy Online Utilities Servus (Business) Banks and Credit Cards Meridian Credit Union Banks and Credit Cards Yes RBC Banks and Credit Cards Yes CIBC Banks and Credit Cards Yes Scotiabank Banks and Credit Cards Yes Interior Savings Credit Union Banks and Credit Cards ATB Financial (Business) Banks and Credit Cards Yes Tangerine (ING Direct) Banks and Credit Cards Yes RBC Express Banks and Credit Cards American Express (Canada) Banks and Credit Cards Yes Westoba Credit Union Banks and Credit Cards BMO Debit Card Banks and Credit Cards Yes President's