The Last Things Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2-22- the Four Last Things

St. Mark Seeker’s Study Guide February 22, 2017: The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell The Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven and hell, are realities of human life. Although our end in this world is not the most attractive topic of conversation, Christians should understand that death is a passage to new life. The Communion of the Saints is the unity of baptized Christians with all who have gone before us in the oneness of God. As Christians, we don’t just prepare for death, but we live that new life today in the sanctifying grace of our God. As we consider the Four Last things, we should do so in the context of faith. Death The Christian Life and Death: The dying should be given attention and care to help them live their last moments in dignity and peace. Assisted suicide or euthanasia are not a morally responsible use of life. The dying should be accompanied and supported. No one ought to feel that they are a burden to others. Part of the challenge of the spiritual life is to both learn to love and to be loved. Why is it harder to be loved? Prayer for the Dying: The dying will be helped by the prayer of their relatives, who must see to it that the sick receive at the proper time the Sacraments that prepare them to meet the living God” (CCC, no. 2299). Death: The final article of the Creed proclaims our belief in everlasting life. At the Catholic Rite of Commendation of the Dying, sometimes prayed at the Anointing of the Sick, we sometimes hear this prayer: “Go forth, Christian soul, from this world... -

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death Part 1--The Remembrance of Death A TREATISE (UNFINISHED) UPON THESE WORDS OF HOLY SCRIPTURE Memorare novissima, & in aeternum non peccabis “Remember the last things, & thou shalt never sin.”—Ecclus. 7 . Made about the year of our Lord 1522, by Sir Thomas More then knight, and one of the Privy Council of King Henry VIII, and also Under-Treasurer of England. If there were any question among men whether the words of holy Scripture or the doctrine of any secular author were of greater force and effect to the weal and profit of man’s soul (though we should let pass so many short and weighty words spoken by the mouth of our Saviour Christ Himself, to Whose heavenly wisdom the wit of none earthly creature can be comparable) yet this only text written by the wise man in the seventh chapter of Ecclesiasticus is such that it containeth more fruitful advice and counsel to the forming and framing of man’s manners in virtue and avoiding of sin, than many whole and great volumes of the best of old philosophers or any other that ever wrote in secular literature. Long would it be to take the best of their words and compare it with these words of holy Writ. Let us consider the fruit and profit of this in itself: which thing, well advised and pondered, shall well declare that of none whole volume of secular literature shall arise so very fruitful doctrine. For what would a man give for a sure medicine that were of such strength that it should all his life keep him from sickness, namely 1 if he might by the avoiding of sickness be sure to continue his life one hundred years? So is it now that these words giveth us all a sure medicine (if we forsloth 2 not the receiving) by which we shall keep from sickness, not the body, which none health may long keep from death (for die we must in few years, live we never so long), but the soul, which here preserved from the sickness of sin, shall after this eternally live in joy and be preserved from the deadly life of everlasting pain. -

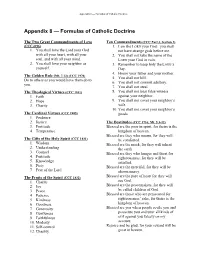

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine The Two Great Commandments of Love Ten Commandments (CCC Part 3, Section 2) (CCC 2196) 1. I am the LORD your God: you shall 1. You shall love the Lord your God not have strange gods before me. with all your heart, with all your 2. You shall not take the name of the soul, and with all your mind. LORD your God in vain. 2. You shall love your neighbor as 3. Remember to keep holy the LORD’s yourself. Day. 4. Honor your father and your mother. The Golden Rule (Mt. 7:12) (CCC 1970) 5. You shall not kill. Do to others as you would have them do to 6. You shall not commit adultery. you. 7. You shall not steal. The Theological Virtues (CCC 1841) 8. You shall not bear false witness 1. Faith against your neighbor. 2. Hope 9. You shall not covet your neighbor’s 3. Charity wife. 10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s The Cardinal Virtues (CCC 1805) goods. 1. Prudence 2. Justice The Beatitudes (CCC 1716; Mt. 5:3-12) 3. Fortitude Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the 4. Temperance kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they will The Gifts of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1831) be comforted. 1. Wisdom Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit 2. Understanding the earth. 3. Counsel Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for 4. Fortitude righteousness, for they will be 5. Knowledge satisfied. -

Pleasures of Gluttony Los Placeres De La Codicia Os Prazeres Da Gula

Pleasures of Gluttony Los placeres de la Codicia Os prazeres da Gula Burçin EROL 1 Abstract: In the late Middle Ages, especially in England, displaying an abundance of food and feasting became not only an act of pleasure but also a means of establishing status and wealth, despite gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. In the fourteenth century – due to various reasons such as increased population, crop failure, the Black Death, and the disruption of food production by warfare – feasting, the displaying of food, and indulgence in gluttony was an indicator of wealth, riches, and high status for the upper class or the social climber as it is well indicated in the works of Chaucer and some of his contemporaries. Resumo: Especialmente na Idade Média Tardia, na Inglaterra, demonstrações de comida abundante e ceias se tornaram não somente um prazer, mas uma representação do estabelecimento de status e riqueza, apesar da gula ser proclamada um dos sete pecados capitais. No século XIV, devido a várias calamidades, como crescimento populacional, problemas na colheita , a peste negra e a quebra da produção de comida, o fornecimento e a ostentação de comida e indulgencia na gula foi um indicador de riqueza grande status para a classe alta ou para ascendentes sociais, como bem indicada nos trabalhos de Chaucer e alguns de seus contemporâneos. Keywords: Seven Deadly Sins – Gluttony – Pleasure – Middle English Literature. Palavras-chaves: Sete Pecados Capitais – Gula – Prazer – Literatura em Inglês Médio. 1 Prof. Dr., Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] . -

AMOS 44 Prophet of Social Justice

AMOS 44 Prophet of Social Justice Introduction. With Amos, we are introduced to the proclamation of Amos’ judgment, but rather in the first of the “writings prophets.” They did not only social evils that demand such judgment. preach but also wrote down their sermons. Preaching prophets like Elijah and Elisha did not write down Style. Amos’ preaching style is blunt, confrontational their sermons. In some books of the Bible, Amos and and insulting. He calls the rich ladies at the local his contemporaries (Hosea, Isaiah, etc.), are country club in Samaria “cows of Basham” (4:1). sometimes called the “Latter Prophets” to distinguish With an agricultural background, he uses symbols he them from the “Former Prophets” (Joshua, Samuel, has experienced on the land: laden wagons, roaring Nathan, etc.). lions, flocks plundered by wild beasts. Historical Context. One of the problems we DIVISION OF CHAPTERS encounter when dealing with the so-called “Latter Prophets” is the lack of historical context for their PART ONE is a collection of oracles against ministry. Since little or nothing is written in the surrounding pagan nations. These oracles imply that historical books about any of the prophets, with the God’s moral law applies not only to his chosen ones exception of Isaiah, scholars have depended on the but to all nations. In this series of condemnations, text of each prophetic book to ascertain the historical Judah and Israel are not excluded (chs 1-2). background of each of the prophets. Some of the books provide very little historical information while PART TWO is a collection of words and woes against others give no clues at all. -

The Four Last Things Reflections on Death, Judgment, Heaven & Hell

THEOLOGY The Four Last Things Reflections on Death, Judgment, Heaven & Hell Regis Martin, S.T.D. LECTURE GUIDE Learn More www.CatholicCourses.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture Summaries LECTURE 1 Introducing the Study of the Last Things.......................................................................4 LECTURE 2 The Christian Conception of Time and Its Relation to the Last Things...8 Feature: The Sacrament of the Present Moment...............................................................12 LECTURE 3 Exploring the Nature and Dynamism of Hope.......................................................14 LECTURE 4 On First Opening the Door of Death..............................................................................18 Feature: The Last Rites.......................................................................................................................22 LECTURE 5 On Seeing Death as a Christian and the Consolation It Brings............... 24 LECTURE 6 The Jig Is Up: On Judgment and the World to Come.........................................28 Feature: Purgatory................................................................................................................................ 32 LECTURE 7 On Going to Hell..............................................................................................................................34 LECTURE 8 On the Reality and Nature of Heaven.............................................................................38 Suggested Reading from Regis Martin, S.T.D.................................................................42 -

MISERICORDES SICUT PATER” the Day I Received My First AARP Mailing, I Knew That I Had Turned a Corner

THE FOUR LAST THINGS II: “MISERICORDES SICUT PATER” The day I received my first AARP mailing, I knew that I had turned a corner. When a dear friend remarked out of the blue– “You realize, don’t you, that you have more years behind you than you have ahead of you on this earth?” Yes, I can do the math, and have known that for some time! I then recalled one of the first pieces that I learned on my saxophone at age 10 was “Nearer my God to Thee.” I’d play it accompanied by my great aunt on the piano! Yes, no matter what, we will all face the judgment seat of Christ, just as Saint Paul recounts to the Corinthians, “For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive good or evil, according to what he has done in the body.” Whether or not that kernel from Scripture is good news is entirely up to us. Do you ever stop to think about this reality? Do you consider judgment day? As the Year of Mercy draws to a close today, it may seem counterintuitive to discuss judgment. But in truth, judgment is not at all in conflict with the Year of Mercy theme, “Merciful as the Father,” because God’s mercy figures prominently in our judgment. So too does His Justice. We’d be delusional to think that our actions in this life ought to be free from scrutiny. I have watched the pundits break down the recent election in excruciating detail, highlighting each candidate’s campaign miscalculations and merits. -

The Four Last Things, VI Why Are the Lustful Punished by a Whirlwind In

The Four Last Things, VI Why are the lustful punished by a whirlwind in the Divine Comedy? It is for the same reason that hell is conceived like a funnel, which is the shape of sin. Sin is easily accomplished at first, but the longer one does it the more cramped and crowded and narrow its sphere becomes, the less pleasure to be had. And when a soul allows lust to take the place of reason, then that vice will throw the sinner to the heights of pleasure and just as fast bring them down into the grip of inordinate sadness and gnawing frustration. And the attractions of lust quickly propel the soul first to this object and then immediately to another. Dante’s right, it is like a whirlwind, with no rhyme or reason. And its end is life without meaning. Dante knows this about the nature of lust, and he knows it is wrong, yet he cannot yet fully process what he saw. He still feels sorry for the damned. The eternal punishment of the unrepentant is too difficult to comprehend. Sure, some punishment is in order, but the thought of punishment eternal does not sit right with him. And this too is an attitude typical of our times, because he saw the great heroes of old like Achilles in the whirlwind, and we do not like our heroes dying. The video games pound this into the brain, so that if you make a mistake, you just push a button and start all over as if nothing happened. -

THE FOUR LAST THINGS IV: “THE CLEAR PATH WAS LOST” “At the Midpoint on the Journey of Life, I Found Myself in a Dark Forest, for the Clear Path Was Lost…” Inferno

THE FOUR LAST THINGS IV: “THE CLEAR PATH WAS LOST” “At the midpoint on the journey of life, I found myself in a dark forest, for the clear path was lost…” Inferno. Canto I. Thus opens Dante Alighieri’s epic work, The Divine Comedy- Inferno. While he was a poet, I’d say he was a pretty good theologian as well. Still, if offered a five-minute “preview” of heaven, I’d likely demur. If shown the “trailer” for hell, I’d run as quickly as possible the other way. Why? In the former case, I might not want to come back to earth, and in the latter, I’d spend the rest of my life in utter fear. To me, either way it is a “lose, lose” proposition. When speaking about hell, we encounter the limits of our human ability to comprehend. Both in Scripture and Tradition, hell has quite rightly been described as the ultimate refusal of God’s love, the final and definitive rejection of His love in our lives. This much makes sense to anyone, save perhaps those who deny its very existence. But what can we say about hell, never having been there? First and foremost, we turn to the words of Scripture, combined with the perennial wisdom of the Church’s faith, guided by the Holy Spirit. Finally, we use our own God-given intellect to form impressions. We cannot escape the warnings of the Scriptures, including the call of Jesus to “Enter through the narrow gate.” (Matthew 7:13) The Catechism states rather bluntly (para. -

Reinterpreting Hieronymus Bosch's Table Top of the Seven

REINTERPRETING HIERONYMUS BOSCH'S TABLE TOP OF THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS AND THE FOUR LAST THINGS THROUGH THE SEVEN DAY PRAYERS OF THE DEVOTIO MODERNA Eunyoung Hwang, B.A., M.F.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2000 APPROVED: Scott Montgomery, Major Professor Larry Gleeson, Committee Member Don Schol, Committee Member and Associate Dean William McCarter, Chair of Art History and Art Education Jack Davis, Dean of the School of Visual Art C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Hwang, Eunyoung, Reinterpreting Hieronymus Bosch's Table Top of the Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things through the Seven Day Prayers of the Devotio Moderna. Master of Arts (Art History), August 2000, 140 pp., 35 illustrations, references, 105 titles. This thesis examines Hieronymus Bosch's Table Top of the Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things. Instead of using an iconographical analysis, the thesis investigates the relationship between Bosch's art and the Devotio Moderna, which has been speculated by many Bosch scholars. For this reason, a close study was done to examine the Devotio Moderna and its influence on Bosch's painting. Particular interest is paid to the seven day prayers of the Devotio Moderna, the subjects depicted in Bosch's painting, how Bosch's painting blesses its viewer during the time of one's prayer, and how the use of gaze ties all of these ideas together. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS…………………………………………………………………………………………… iv Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Statement of the Problem Methodology Review of Literature 2. -

Joel 3 Divine Judgment: Know Justice, Know Peace

Joel 3 Divine Judgment: know justice, know peace Let’s Review Joel 1:1-18 and 2:2-11 a recent Locust plague points to God’s future judgement Word images from appearances of God in Exodus used to describe this day: Darkness Fire Earthquake Heavens tremble and darken Joel 2:12-14 reminder of God’s compassionate love and His call to repent Joel 2:18-27 the future day of the Lord will radically change all things Removal of evil and suffering Abundance beyond measure Presence of God with His people Creation as a whole will be blessed The Kingdom of God is Already, but Not Yet This is accomplished at the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus Christ and initiated at Pentecost with the arrival of the Holy Spirit to indwell all God’s new covenant people and all of this will be finalized at the Return of Christ. We are in what biblical scholars refer to as the Already, but Not Yet era of the Kingdom of God. Joel Overview: The Day of the Lord brings Disaster and Blessing Locust Plague is Immediate Disaster from God 1:2-20 Summons to Fasting and Prayer to God 1:13-14 Locust Plague as Impending Disaster from God 2:1-17 Call to Repentance 2:12-14 God will Respond 2:18-32 Removal of the Threat 2:18-20 Healing in the Land 2:21-34 Restoration of Blessing 2:25-27 Salvation for all who call upon the Lord 2:28-32 Spirit upon all God’s people 2:28-29 God’s judgment upon all people who live in opposition 3:1-16 Reversal of fortune = Slavers will be enslaved 1-8 Retribution for sin = enemies of God summoned 10-16 Let’s quick walk thru Joel 3:1-16 Verse 1 “At the time of those event…I will restore the prosperity of Judah and Jerusalem” context 2:28 “Then, after doing all these things, I will pour out my Spirit upon all people”. -

The Last Things Because, by Definition, Purgatory Is Temporary

The Four Last Things Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell • ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ - Dante’s Inferno • ‘Life is passing. Eternity draws closer; soon we will live the very life of God.’ - St. Therese of Lisieux Why are they called the “last things?” • Because they are definitive • Purgatory is not included in the traditional list of the last things because, by definition, purgatory is temporary. • All those in purgatory are destined for the eternal bliss of heaven • In the end, there will be no one in purgatory Death • Death is not natural; i.e., it was not part of God’s original creation. Death came as punishment for sin. • St. Paul reaffirms this in the New Testament, where he says “sin came into the world through one man (Adam) and death through sin” (Rom. 5:12) and a little later says, “the wages of sin is death” (Rom. 6:23). • In the case of those justified by grace in Jesus Christ, death loses its penal character and becomes a mere consequence of sin and the gateway to eternal life in heaven. • Death consists of the separation of the soul from the body Death • It is wise to remember the fact of our own mortality often… • “Teach us to number our days aright, that we may gain wisdom of heart.” (Ps 90:12) • “What mortal can live and not see death? Who can escape the power of the grave?” (Ps 89:49) • Monastic traditions – “Hodie mihi, cras tibi” • Not macabre – rather a reminder that our time on earth is limited and that what we do now matters for eternity.