Reinterpreting Hieronymus Bosch's Table Top of the Seven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Deadly Sins Online

CnMQg (Free and download) Seven Deadly Sins Online [CnMQg.ebook] Seven Deadly Sins Pdf Free Kevin Vost DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #228218 in Books 2015-05-19Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.50 x .60 x 5.50l, .0 #File Name: 162282234X224 pages | File size: 72.Mb Kevin Vost : Seven Deadly Sins before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Seven Deadly Sins: 36 of 36 people found the following review helpful. This Book Brings Clarity to Spiritual Weaponry to Fend Off EvilBy TJ BurdickIn this book, Dr. Vost takes his expertise of the human mind and unites it with the timeless truths of Thomas Aquinas’ work in order to help the reader form a psychological army to battle against sin. By pitting vice against virtue, he joins faith and reason to do war against evil on the battlefields of both the mind and the soul.“Although I am certainly unable to advise anyone from the perspective of one who has conquered these sins himself, I do stand ready to point you to the strategies and arm you with some of the weapons that great saints have devised to assist us in our relentless struggles against sin, toward virtue, and ultimately, toward union with God” (p.83).The first part of the book goes back to the early Church and creates a symmetrical consensus of just what the deadly sins are. Vost’s research of the historical and etymological interpretations of the names for each of the seven deadly, or capital, sins is exhaustive and complete.He then dissects each of the seven deadly sins with the literary scalpel of what St. -

2-22- the Four Last Things

St. Mark Seeker’s Study Guide February 22, 2017: The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell The Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven and hell, are realities of human life. Although our end in this world is not the most attractive topic of conversation, Christians should understand that death is a passage to new life. The Communion of the Saints is the unity of baptized Christians with all who have gone before us in the oneness of God. As Christians, we don’t just prepare for death, but we live that new life today in the sanctifying grace of our God. As we consider the Four Last things, we should do so in the context of faith. Death The Christian Life and Death: The dying should be given attention and care to help them live their last moments in dignity and peace. Assisted suicide or euthanasia are not a morally responsible use of life. The dying should be accompanied and supported. No one ought to feel that they are a burden to others. Part of the challenge of the spiritual life is to both learn to love and to be loved. Why is it harder to be loved? Prayer for the Dying: The dying will be helped by the prayer of their relatives, who must see to it that the sick receive at the proper time the Sacraments that prepare them to meet the living God” (CCC, no. 2299). Death: The final article of the Creed proclaims our belief in everlasting life. At the Catholic Rite of Commendation of the Dying, sometimes prayed at the Anointing of the Sick, we sometimes hear this prayer: “Go forth, Christian soul, from this world... -

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death Part 1--The Remembrance of Death A TREATISE (UNFINISHED) UPON THESE WORDS OF HOLY SCRIPTURE Memorare novissima, & in aeternum non peccabis “Remember the last things, & thou shalt never sin.”—Ecclus. 7 . Made about the year of our Lord 1522, by Sir Thomas More then knight, and one of the Privy Council of King Henry VIII, and also Under-Treasurer of England. If there were any question among men whether the words of holy Scripture or the doctrine of any secular author were of greater force and effect to the weal and profit of man’s soul (though we should let pass so many short and weighty words spoken by the mouth of our Saviour Christ Himself, to Whose heavenly wisdom the wit of none earthly creature can be comparable) yet this only text written by the wise man in the seventh chapter of Ecclesiasticus is such that it containeth more fruitful advice and counsel to the forming and framing of man’s manners in virtue and avoiding of sin, than many whole and great volumes of the best of old philosophers or any other that ever wrote in secular literature. Long would it be to take the best of their words and compare it with these words of holy Writ. Let us consider the fruit and profit of this in itself: which thing, well advised and pondered, shall well declare that of none whole volume of secular literature shall arise so very fruitful doctrine. For what would a man give for a sure medicine that were of such strength that it should all his life keep him from sickness, namely 1 if he might by the avoiding of sickness be sure to continue his life one hundred years? So is it now that these words giveth us all a sure medicine (if we forsloth 2 not the receiving) by which we shall keep from sickness, not the body, which none health may long keep from death (for die we must in few years, live we never so long), but the soul, which here preserved from the sickness of sin, shall after this eternally live in joy and be preserved from the deadly life of everlasting pain. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

The Seven Deadly Sins

THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS "The lesson writ in red since first time ran, A hunter hunting down the beast in man; That till the chasing out of its last vice, The flesh was fashioned but for sacrifice." GEORGE MEREDITH xenrht IDas h<mtmi(# Snjferbta, /mJ/i S—^5^T\ ~t{?H placcOjjfltKeo dmti mmtsi^/a mi/'i. s* / PRIDE. (After Goltziits.) [Frontispiece. THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS BY FREDERICK ROGERS A. H. BULLEN 47, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. I907 TO ARTHUR C. HAYWARD WITH WHOM I HAVE READ MANY BOOKS AND FROM WHOM I HAVE HAD MUCH FRIENDSHIP I DEDICATE THESE PAGES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION LIST OF SINS AND VIRTUES WORKS OF MERCY, SPIRITUAL GIFTS, AND PENITENTIAL PSALMS PAGE CHAPTER I. THE SINS AND THE CHURCH 1 CHAPTER II. THE SINS AND RELIGIOUS DRAMA - 11 CHAPTER III. THE SINS AND SOCIAL REVOLT - r 29 CHAPTER IV. THE SINS IN COMMON LIFE - 44 CHAPTER V. THE SINS AND THE REFORMATION - - 62 CHAPTER VI. THE SINS AND THE ELIZABETHANS - - 74 CHAPTER VII. EXEUNT THE SINS ----- - 98 ILLUSTRATIONS PRIDE (after Goltzws) . FRONTISPIECE TO FACE PAGE PRIDE (after De Vos) . 8 LECHERY „ . 18 ENVY „ • 32 WRATH „ . 42 COVETOUSNESS „ . 58 GLUTTONY „ .70 SLOTH „ . 80 WRATH (after Peter Brueghil) . : . 88 AVARICE „ . IOO INTRODUCTION HE business of literature is the presentation Tof life, all true literature resolves itself into that. No presentation of life is complete without its sins, and every master of literary art has known it, from the poet King of Israel to Robert Browning. The imagination of the Middle Ages, in many ways more virile and expansive than our own, had a strong grasp of this fact, and realised that it is the sense of fault or error that lies at the root of every forward movement, that there is no real progress unless it is accompanied by a sense of sin. -

The Evolution of the Seven Deadly Sins: from God to the Simpsons

96 Journal of Popular Culture sin. A lot. As early Christian doctrine repeatedly points out, the seven deadly sins are so deeply rooted in our fallen human nature, that not only are they almost completely unavoidable, but like a proverbial bag of The Evolution of the Seven Deadly Sins: potato chips, we can never seem to limit ourselves to just one. With this ideology, modern society agrees. However, with regard to the individual From God to the Simpsons and social effects of the consequences of these sins, we do not. The deadly sins of seven were identified, revised, and revised again Lisa Frank in the heads and classrooms of reportedly celibate monks as moral and philosophical lessons taught in an effort to arm men and women against I can personally attest that the seven deadly sins are still very much the temptations of sin and vice in the battle for their souls. These teach- with us. Today, I have committed each of them, several more than once, ings were quickly reflected in the literature, theater, art, and music of before my lunch hour even began. Here is my schedule of sin (judge me that time and throughout the centuries to follow. Today, they remain pop- if you will): ular motifs in those media, as well as having made the natural progres- sion into film and television. Every day and every hour, acts of gluttony, 7:00 - I pressed the snooze button three times before dragging myself out of lust, covetousness, envy, pride, wrath, and sloth are portrayed on televi- bed. -

The Moneylender and His Wife by Quentin Metsys (1466-1530) Oil on Panel 1514

The Moneylender and His Wife By Quentin Metsys (1466-1530) Oil on panel 1514 ABOUT THE ARTIST: Born in Louvain, Belgium in 1466, Quentin Metsys was trained as an ironsmith before becoming a painter and later settling in Antwerp, Belgium where in 1491 he is mentioned as a master in the guild of painters. At this time, Antwerp was the center of economic activity in the Low Countries which were comprised of Flanders (Northern Belgium) and the Netherlands. The growth and prosperity of Antwerp also attracted many artists who benefitted from the wealthy merchants who would collect and purchase their art. Metsys became Antwerp’s leading artist and founder of the Antwerp School. There is little known of Metsys’s artistic training but his style reflects the influence of multiple artists. “Matsys’ firmness of outline, clear modelling and thorough finish of detail stem from Van de Weyden's influence; from the Van Eycks and Memling by way of Dirck Bouts, the glowing richness of transparent pigments.” Other artists that have been referenced are Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Durer, Hans Holbein and Leonardo da Vinci. Not only is a religious influence felt in Metsys’s paintings, which was typical of traditional Flemish works, but he included a bit of satire as well. Metsys died in Antwerp in 1530. To mark the first centennial of his death there was a ceremony and a relief plaque with an additional inscription on the facade of the Antwerp Cathedral. Cornelius van der Geest, a patron, came up with the wording: "in his time a smith and afterwards a famous painter" honoring Metsys’ life. -

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Jheronimus Bosch-His Sources

In the concluding review of his 1987 monograph on Jheronimus Bosch, Roger Marijnissen wrote: ‘In essays and studies on Bosch, too little attention has been paid to the people who Jheronimus Bosch: his Patrons and actually ordered paintings from him’. 1 And in L’ABCdaire de Jérôme Bosch , a French book published in 2001, the same author warned: ‘Ignoring the original destination and function his Public of a painting, one is bound to lose the right path. The function remains a basic element, and What we know and would like to know even the starting point of all research. In Bosch’s day, it was the main reason for a painting to exist’. 2 The third International Bosch Conference focuses precisely on this aspect, as we can read from the official announcement (’s-Hertogenbosch, September 2012): ‘New information Eric De Bruyn about the patrons of Bosch is of extraordinary importance, since such data will allow for a much better understanding of the original function of these paintings’. Gathering further information about the initial reception of Bosch’s works is indeed one of the urgent desiderata of Bosch research for the years to come. The objective of this introductory paper is to offer a state of affairs (up to September 2012) concerning the research on Bosch’s patronage and on the original function of his paintings. I will focus on those things that can be considered proven facts but I will also briefly mention what seem to be the most interesting hypotheses and signal a number of desiderata for future research. -

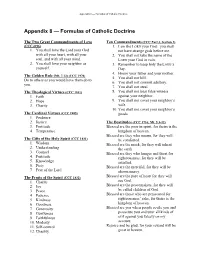

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine The Two Great Commandments of Love Ten Commandments (CCC Part 3, Section 2) (CCC 2196) 1. I am the LORD your God: you shall 1. You shall love the Lord your God not have strange gods before me. with all your heart, with all your 2. You shall not take the name of the soul, and with all your mind. LORD your God in vain. 2. You shall love your neighbor as 3. Remember to keep holy the LORD’s yourself. Day. 4. Honor your father and your mother. The Golden Rule (Mt. 7:12) (CCC 1970) 5. You shall not kill. Do to others as you would have them do to 6. You shall not commit adultery. you. 7. You shall not steal. The Theological Virtues (CCC 1841) 8. You shall not bear false witness 1. Faith against your neighbor. 2. Hope 9. You shall not covet your neighbor’s 3. Charity wife. 10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s The Cardinal Virtues (CCC 1805) goods. 1. Prudence 2. Justice The Beatitudes (CCC 1716; Mt. 5:3-12) 3. Fortitude Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the 4. Temperance kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they will The Gifts of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1831) be comforted. 1. Wisdom Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit 2. Understanding the earth. 3. Counsel Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for 4. Fortitude righteousness, for they will be 5. Knowledge satisfied. -

Pleasures of Gluttony Los Placeres De La Codicia Os Prazeres Da Gula

Pleasures of Gluttony Los placeres de la Codicia Os prazeres da Gula Burçin EROL 1 Abstract: In the late Middle Ages, especially in England, displaying an abundance of food and feasting became not only an act of pleasure but also a means of establishing status and wealth, despite gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. In the fourteenth century – due to various reasons such as increased population, crop failure, the Black Death, and the disruption of food production by warfare – feasting, the displaying of food, and indulgence in gluttony was an indicator of wealth, riches, and high status for the upper class or the social climber as it is well indicated in the works of Chaucer and some of his contemporaries. Resumo: Especialmente na Idade Média Tardia, na Inglaterra, demonstrações de comida abundante e ceias se tornaram não somente um prazer, mas uma representação do estabelecimento de status e riqueza, apesar da gula ser proclamada um dos sete pecados capitais. No século XIV, devido a várias calamidades, como crescimento populacional, problemas na colheita , a peste negra e a quebra da produção de comida, o fornecimento e a ostentação de comida e indulgencia na gula foi um indicador de riqueza grande status para a classe alta ou para ascendentes sociais, como bem indicada nos trabalhos de Chaucer e alguns de seus contemporâneos. Keywords: Seven Deadly Sins – Gluttony – Pleasure – Middle English Literature. Palavras-chaves: Sete Pecados Capitais – Gula – Prazer – Literatura em Inglês Médio. 1 Prof. Dr., Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] . -

A New Look at the Cure of Folly

Medical History, 1978, 22: 267-281. A NEW LOOK AT THE CURE OF FOLLY by WILLIAM SCHUPBACH* THE MEDICAL and surgical scenes depicted by Netherlandish artists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have attracted the admiring attention of historians of medicine to such a degree that almost no book on "art and medicine" omits such paintings as Jan Steen's A love-sick (or pregnant) girl visited by a physician (several versions) or Gerrit Dou's Quacksalver (Rotterdam, Boymans-van Beuningen museum), although their documentary value is problematical.' Almost as popular are the paint- ings and graphics which illustrate the scene known in Dutch as Het snijden van den kei, in French as La pierre de tte or La pierre defolie, in English as The cure offolly, and in German as Der Steinschneider. In these scenes, a medical practitioner- physician, surgeon, barber-surgeon or quack, or a combination of those four-makes an incision in the patient's scalp and appears to extract from it a foreign body, usually a stone, the pierre de tete, which, according to contemporary inscriptions, had caused the patient to be afflicted with some kind of mental disorder ("folly"). One of the first modem writers to discuss these scenes, writing about the version in the Prado (Madrid) which is attributed to Hieronymus Bosch, interpreted it as a fantastic suggestion to the surgeons, comparable to Swift's suggestion of reciprocal hind-brain transplants for contentious politicians.2 This interpretation was soon overcast by another, which was first put forward by Henry Meige of the Salpetri6re in a fascinating and persuasive series of articles.3 The Persian physician Rhazes *William Schupbach, M.A., Weilcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BP.