Geologic Setting of the Phoenix Lander Mission Landing Site Tabatha Heet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

50 Years of Petrology

spe500-01 1st pgs page 1 The Geological Society of America 18888 201320 Special Paper 500 2013 CELEBRATING ADVANCES IN GEOSCIENCE Plates, planets, and phase changes: 50 years of petrology David Walker* Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA ABSTRACT Three advances of the previous half-century fundamentally altered petrology, along with the rest of the Earth sciences. Planetary exploration, plate tectonics, and a plethora of new tools all changed the way we understand, and the way we explore, our natural world. And yet the same large questions in petrology remain the same large questions. We now have more information and understanding, but we still wish to know the following. How do we account for the variety of rock types that are found? What does the variety and distribution of these materials in time and space tell us? Have there been secular changes to these patterns, and are there future implications? This review examines these bigger questions in the context of our new understand- ings and suggests the extent to which these questions have been answered. We now do know how the early evolution of planets can proceed from examples other than Earth, how the broad rock cycle of the present plate tectonic regime of Earth works, how the lithosphere atmosphere hydrosphere and biosphere have some connections to each other, and how our resources depend on all these things. We have learned that small planets, whose early histories have not been erased, go through a wholesale igneous processing essentially coeval with their formation. -

Field Measurements of Terrestrial and Martian Dust Devils Journal Item

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Field Measurements of Terrestrial and Martian Dust Devils Journal Item How to cite: Murphy, Jim; Steakley, Kathryn; Balme, Matt; Deprez, Gregoire; Esposito, Francesca; Kahanpää, Henrik; Lemmon, Mark; Lorenz, Ralph; Murdoch, Naomi; Neakrase, Lynn; Patel, Manish and Whelley, Patrick (2016). Field Measurements of Terrestrial and Martian Dust Devils. Space Science Reviews, 203(1) pp. 39–87. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 Springer https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s11214-016-0283-y Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 1 Field Measurements of Terrestrial and Martian Dust Devils 2 Jim Murphy1, Kathryn Steakley1, Matt Balme2, Gregoire Deprez3, Francesca 3 Esposito4, Henrik Kahapää5, Mark Lemmon6, Ralph Lorenz7, Naomi Murdoch8, Lynn 4 Neakrase1, Manish Patel2, Patrick Whelley9 5 1-New Mexico State University, Las Cruces NM, USA 2 - Open University, Milton Keynes UK 6 3 - Laboratoire Atmosphères, Guyancourt, France 4 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di 7 Capodimonte, Naples, Italy 5 - Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki, Finland 6 - Texas 8 A&M University, College Station TX, USA 7 -Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 9 Laurel MD USA 8 - ISAE-SUPAERO, Toulouse University, France 9 - NASA Goddard 10 Space Flight Center, Greenbelt MD, USA 11 submitted to SSR 10 May, 2016 12 Revised manuscript 08 August 2016 13 ABSTRACT 14 Surface-based measurements of terrestrial and martian dust devils/convective vortices 15 provided from mobile and stationary platforms are discussed. -

Chemical and Isotopic Studies of Monogenetic Volcanic Fields: Implications for Petrogenesis and Mantle Source Heterogeneity

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Christine Rasoazanamparany Candidate for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ______________________________________ Elisabeth Widom, Director ______________________________________ William K. Hart, Reader ______________________________________ Mike R. Brudzinski, Reader ______________________________________ Marie-Noelle Guilbaud, Reader ______________________________________ Hong Wang, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT CHEMICAL AND ISOTOPIC STUDIES OF MONOGENETIC VOLCANIC FIELDS: IMPLICATIONS FOR PETROGENESIS AND MANTLE SOURCE HETEROGENEITY by Christine Rasoazanamparany The primary goal of this dissertation was to investigate the petrogenetic processes operating in young, monogenetic volcanic systems in diverse tectonic settings, through detailed field studies, elemental analysis, and Sr-Nd-Pb-Hf-Os-O isotopic compositions. The targeted study areas include the Lunar Crater Volcanic Field, Nevada, an area of relatively recent volcanism within the Basin and Range province; and the Michoacán and Sierra Chichinautzin Volcanic Fields in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which are linked to modern subduction. In these studies, key questions include (1) the role of crustal assimilation vs. mantle source enrichment in producing chemical and isotopic heterogeneity in the eruptive products, (2) the origin of the mantle heterogeneity, and (3) the cause of spatial-temporal variability in the sources of magmatism. In all three studies it was shown that there is significant compositional variability within individual volcanoes and/or across the volcanic field that cannot be attributed to assimilation of crust during magmatic differentiation, but instead is attributed to mantle source heterogeneity. In the first study, which focused on the Lunar Crater Volcanic Field, it was further shown that the mantle heterogeneity is formed by ancient crustal recycling plus contribution from hydrous fluid related to subsequent subduction. -

Water on the Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity

Water on The Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity Arlin Crotts (Columbia University) For centuries some scientists have argued that there is activity on the Moon (or water, as recounted in Parts I & II), while others have thought the Moon is simply a dead, inactive world. [1] The question comes in several forms: is there a detectable atmosphere? Does the surface of the Moon change? What causes interior seismic activity? From a more modern viewpoint, we now know that as much carbon monoxide as water was excavated during the LCROSS impact, as detailed in Part I, and a comparable amount of other volatiles were found. At one time the Moon outgassed prodigious amounts of water and hydrogen in volcanic fire fountains, but released similar amounts of volatile sulfur (or SO2), and presumably large amounts of carbon dioxide or monoxide, if theory is to be believed. So water on the Moon is associated with other gases. Astronomers have agreed for centuries that there is no firm evidence for “weather” on the Moon visible from Earth, and little evidence of thick atmosphere. [2] How would one detect the Moon’s atmosphere from Earth? An obvious means is atmospheric refraction. As you watch the Sun set, its image is displaced by Earth’s atmospheric refraction at the horizon from the position it would have if there were no atmosphere, by roughly 0.6 degree (a bit more than the Sun’s angular diameter). On the Moon, any atmosphere would cause an analogous effect for a star passing behind the Moon during an occultation (multiplied by two since the light travels both into and out of the lunar atmosphere). -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

In Pdf Format

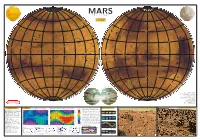

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

IRPA13 Final Program

IRPA13 v v Final Programme v DOCHART CARRON To Clyde Auditorium, Forth and Gala Rooms and Hotel HALL 4 LOMOND BOISDALE ALSH 13 - 18 May 2012 CLYDE AUDITORIUMCLYDE AUDITORIUM Magnox Fuel Pond Alternative ILW Treatment Bradwell turbine hall MagnoxDecommissioning Fuel Pond Alternative& Disposition ILW Treatment demolitionBradwell turbine hall FORTH ROOM Decommissioning & Disposition demolition (GROUND FLOOR) GALA ROOM (FIRST FLOOR) ProvidingProviding integrated integrated services andand solutions to the global nuclear industry TOILETS (WC’s) M-MALE F-FEMALE TOILETS CLOAKROOM solutions to the global nuclear industry TOILETS FOR DISABLED SHOP EnergySolutions is an international nuclear services company MEDICAL CENTRE BABYCARE ROOMS Magnox Fuel Pond Alternative ILW Treatment Bradwell turbine hall INFORMATION & BUSINESS CENTRE CATERING DecommissioningEnergywith operationsSolutions aroundis& anDisposition international the world, Energy nuclearSolutions’ servicesdemolition work company BOX OFFICE LIFT withspans operations the nuclear around life cycle the world, from operating EnergySolutions’ nuclear power work BANK RECEPTION spansstations the throughnuclear late-life life cycle management from operating and on nuclear to defueling, power stationsdecommissioning, through late-life waste management processing and and packaging, on to defueling, and Providingdecommissioning,complete integrated site restoration. waste processing services and packaging, and and complete site restoration. Registration, Exhibition, solutionsIn the UK,to wethe manage, global on behalf nuclear of the Nuclear industry Hall 4 SECC, Glasgow Posters and Catering Decommissioning Authority, 22 Magnox reactors across 10 In sites,the UK, over we seeing manage, the safe on behalfdelivery of of the continued Nuclear operations. Opening Ceremony, Plenary EnergyDecommissioningSolutions is an Authorit internationaly, 22 Magnox nuclear reactors services across 10 company Clyde Auditorium sites,For further over information seeing contact: the safe delivery of continued operations. -

Discovery of Jarosite Within the Mawrth Vallis Region of Mars: Implications for the Geologic History of the Region

Icarus 204 (2009) 478–488 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Discovery of jarosite within the Mawrth Vallis region of Mars: Implications for the geologic history of the region William H. Farrand a,*, Timothy D. Glotch b, James W. Rice Jr. c, Joel A. Hurowitz d, Gregg A. Swayze e a Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut St., #205, Boulder, CO 80301, USA b Stony Brook University, Department of Geosciences, 255 Earth and Space Sciences Building, Stony Brook, NY 11794-2100, USA c Arizona State University, School of Earth and Space Exploration, P.O. Box 871404, Tempe, AZ 85287-6305, USA d Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Mail Stop 183-501, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA e U.S. Geological Survey, Box 25046, Denver Federal Center Mail Stop 964, Denver, CO 80225-0046, USA article info abstract Article history: Analysis of visible to near infrared reflectance data from the MRO CRISM hyperspectral imager has Received 20 March 2009 revealed the presence of an ovoid-shaped landform, approximately 3 by 5 km in size, within the layered Revised 12 June 2009 terrains surrounding the Mawrth Vallis outflow channel. This feature has spectral absorption features Accepted 3 July 2009 consistent with the presence of the ferric sulfate mineral jarosite, specifically a K-bearing jarosite (KFe - Available online 17 July 2009 3 (SO4)2(OH)6). Terrestrial jarosite is formed through the oxidation of iron sulfides in acidic environments or from basaltic precursor minerals with the addition of sulfur. Previously identified phyllosilicates in the Keywords: Mawrth Vallis layered terrains include a basal sequence of layers containing Fe–Mg smectites and an Mars upper set of layers of hydrated silica and aluminous phyllosilicates. -

Rochechouart As Natural Impact Laboratory: a Review

46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 1915.pdf ROCHECHOUART AS NATURAL IMPACT LABORATORY: A REVIEW. P. Lambert, Sciences & Applica- tions, Bd Albert 1er, 33800 Bordeaux, France. E-mail: [email protected]. Introduction: The planetary importance of impact shock studies and preliminary gravimetric investiga- as a natural process is well acknowledged today, but tions [2,7]. The initial crater must have been larger. the recognition and studies of impacts are very recent. Recent work by [8] agrees with the 40-50 km diameter Fundamental aspects such as how large impacts get proposed earlier by [3]. 2-Position of the center of the their final shape are still not well understood. Also we crater: The largest coherent melt-rich impactite occur- are still at the onset of discovering and evaluating ma- ring at Montoume is interpreted by [8] as the center of jor incidences such as emergence of life both in the the crater, 6 km south of the center admitted so far Early Earth and on other Planetary Bodies. Research on from the distribution of shock in both the target and the the above mentioned issues has focused so far on theo- breccia deposit [2] and from preliminary gravimetric retical approaches and mathematical models. These studies [7]. Points 1 and 2 call for combined detailed need to be constrained and validated by ground truth gravimetric, petrographic and micro-meso-tectonic data. In that frame, terrestrial impacts are and will re- studies outside the breccia deposits where most of the main by far the most accessible data reservoir. This research has been focusing until today.