Lester Young, Charlie Parker, James Moody, Nat "King" History, but It Was Never Really Appealing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board James Abbington, DMA Associate Professor of Church Music and Worship Candler School of Theology, Emory University William C. Banfield, DMA Professor of Africana Studies, Music, and Society Berklee College of Music Johann Buis, DA Associate Professor of Music History Wheaton College Eileen M. Hayes, PhD Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology College of Music, University of North Texas Cheryl L. Keyes, PhD Professor of Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles Portia K. Maultsby, PhD Professor of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Director of the Archives of African American Music and Culture Indiana University, Bloomington Ingrid Monson, PhD Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music Harvard University Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., PhD Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music University of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia of African American Music Volume 1: A–G Emmett G. Price III, Executive Editor Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Associate Editors Copyright 2011 by Emmett G. Price III, Tammy L. Kernodle, and Horace J. Maxile, Jr. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of African American music / Emmett G. Price III, executive editor ; Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., associate editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1 (set hard copy : alk. -

Chicago Tribune

Colsons return to Chicago with new sounds Adegoke Steve Colson and Iqua Colson bring their experimental music to Constellation on Saturday, Aug. 12, 2017. (Mikel Colson photo) By Howard Reich Chicago Tribune AUGUST 9, 2017, 9:25 AM early 50 years ago, a promising young pianist from New Jersey began studying music at N Northwestern University — and discovered sounds he’d never encountered before. Not so much at school, where classical music predominated, but elsewhere in Evanston and Chicago, where musical revolutions were underway. For just two years before Adegoke Steve Colson came here in 1967, a contingent of fearlessly innovative South Side artists had formed the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a collective that was inventing radical new techniques, concepts and practices for composing and improvising music. Even closer to campus, saxophonist Fred Anderson was making his Birdhouse venue in Evanston a nexus for new music and became an early mentor to Colson. The creative ferment of that period transformed Colson, who will return to Chicago to co-lead a quintet with vocalist Iqua Colson, his wife, Saturday night at Constellation. As he prepares for this engagement, memories of those early days come flooding back. “I remember I saw a flyer for Fred Anderson, because he lived there in Evanston … and we could go by and join his band,” says pianist Colson, who often sat in with the singular improviser. “When I started playing with guys in the AACM. Sometimes (bassist) Fred Hopkins would show up, (drummer) Steve McCall would show up,” adds Colson, who formed a jazz band with fellow student Chico Freeman. -

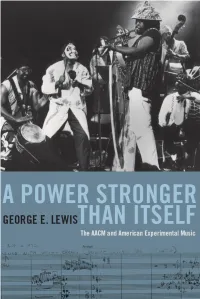

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

Ears Embiggened: Icons

Ears Embiggened: Icons (The fifth in a series of preview posts as we count down to the 2019 Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, TN. Part 1 here on the 50 year legacy of ECM Records. Part 2 here on 50 years of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future. Part 3 here on the magnificent Rhiannon Giddens and her Lucy Negro, Redux project. Part 4 takes a stroll through the league of guitarists on tap.) We often hear an artist described as an overnight sensation, even though in almost every case we are hearing about someone who has put in the work and paid the dues to arrive at their ‘instant’ success. But you never really hear about an overnight icon. Defined as “a person or thing regarded as a representative symbol or as worthy of veneration,” icon status is almost always predicated on longevity, extended and sustained effort, and definitional achievement in a field of endeavor. Exceptions: Bright flaming rockets that burn out fast but leave an unmistakable imprint, and even then, icon status usually has to wait a while. Cf. Hendrix, James Dean, Duane Allman, &c. These are the artists who have helped define their fields, the people that serious younger artists study and obsess about. Big Ears has a pretty good track record of lining up artists that qualify for icon status. 2019 is no exception. I’ve already written about some of these: Art Ensemble of Chicago, Bill Frisell, ECM Records, Richard Thompson. Time to take a look at the rest. -

Chicago Music Communities and the Everyday Significance of Playing Jazz

MUSIC PRACTICES AS SOCIAL RELATIONS: CHICAGO MUSIC COMMUNITIES AND THE EVERYDAY SIGNIFICANCE OF PLAYING JAZZ by John Frederic Behling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mark Allan Clague, Chair Professor Paul A. Anderson Professor Kelly M. Askew Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett Copyright John Frederic Behling 2010 Acknowledgements In this dissertation, I argue that the solos of jazz musicians spring from the practices of the communities in which they live. What holds true for expression and creativity in jazz is no less true of academic research and writing. This dissertation would not be possible without the support and encouragement of many communities and individuals. I thank all the musicians in Chicago who played music with me and welcomed me into their communities. I am especially grateful to Aki Antonia Smith, Edwina Smith, Scott Earl Holman, and Ed Breazeale for befriending me and introducing me to the musicians and communities about whom I write. I am also grateful for the support of my academic community. Kelly Askew introduced me to the anthropological side of ethnomusicology. Her writing showed me what compassionate and concrete ethnography should be like. Paul Anderson’s late night seminars helped me understand that musical practices have philosophical and psychological significance and that jazz criticism is part of a much larger and long- standing intellectual conversation. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, a late addition to my committee, embraced this project with enthusiasm. His generous encouragement and insightful comments are greatly appreciated. -

2014 NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony and Concert Honoring the 2014 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

Monday Evening, January 13, 2014, at 7:30 Wynton Marsalis, Managing and Artistic Director Greg Scholl, Executive Director 2014 NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony and Concert Honoring the 2014 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters JAMEY AEBERSOLD ANTHONY BRAXTON RICHARD DAVIS KEITH JARRETT There will be no intermission during the presentation. Please turn off your cell phones and other electronic devices. Jazz at Lincoln Center thanks its season sponsors: Bloomberg, Brooks Brothers, The Coca-Cola Company, Con Edison, Entergy, HSBC Bank, MasterCard ®, The Shops at Columbus Circle at Time Warner Center, and SiriusXM. Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Please make certain your cellular phone, The Allen Room pager, or watch alarm is switched off. Frederick P. Rose Hall jalc.org Jazz at Lincoln Center 2014 NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony and Concert with NEA JAZZ MASTERS KENNY BARRON (2010), Piano JIMMY HEATH (2003), Tenor Saxophone DAVE LIEBMAN (2011), Soprano Saxophone JIMMY OWENS (2012), Trumpet and Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition Winners MELISSA ALDANA (2013), Saxophone KRIS BOWERS (2011), Piano JAMISON ROSS (2012), Drums Special Guests TAYLOR HO BYNUM, Cornet ANN HAMPTON CALLAWAY, Vocals AMINA FIGAROVA, Piano BILL FRISELL, Guitar RUSSELL HALL, Bass MARY HALVORSON, Guitar BRUCE HARRIS, Trumpet INGRID LAUBROCK, Tenor Saxophone JOE LOVANO, Saxophone JASON MORAN, Piano YASUSHI NAKAMURA, Bass CHRIS PATTISHALL, Piano ANNE RHODES, Soprano Vocals VINCE VINCENT, Baritone Vocals MARK WHITFIELD, JR., Drums WARREN WOLF, Vibraphone Jazz at Lincoln Center and the National Endowment for the Arts gratefully thank 60 Minutes for their participation and production of the 2014 NEA Jazz Masters video biographies directed by Anya Bourg. -

Original Music and the Birth of the Aacm

ECSTATIC ENSEMBLE: DESPONT & NUSSBAUM “I don’t stand to benefit when musicians.” Their Chicago headquarters moved frequently, but the format remained constant: everybody is just trying to be like members paid dues to support rentals for everyone else. All of us are highly venues, shared maintenance and promotional duties, and professional musicians were individualized beings, different.” required to teach at the AACM School. –ROSCOE MITCHELL At the time of the AACM's founding in May 1965, Chicago was heavily segregated and its black neighborhoods criminally underserved. There Ecstatic Ensemble: What makes music original? We often use were virtually no opportunities for black “original” to mean unique, but it also refers to composers, and it was rare for black musicians the first, the root, the pattern. For the past five to teach at high levels, join orchestras, or be Original Music decades the Association for the Advancement fairly compensated by local venues and record of Creative Musicians has sought to answer labels. High school teaching jobs were often the this question and produced music that resists only opportunities open to trained musicians, and the Birth of category. Reluctantly labeled jazz, avant-garde, and even those who had achieved widespread classical, electronic—the sonic universe of the success struggled to maintain creative freedom AACM is built on a philosophy of inclusiveness. and fair compensation. “We looked at the lives the AACM of great musicians that were just out there on Known for having produced some of Chicago’s their own, like Charlie Parker,” remembered most renowned musicians and composers such by Catherine Despont Roscoe Mitchell, an original member and widely as Roscoe Mitchell, George Lewis, Joseph and Jake Nussbaum acclaimed saxophonist. -

Gram JAZZ PROMOTING and NURTURING JAZZ in CHICAGO FEBRUARY 2020

gram JAZZ PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO FEBRUARY 2020 WWW.JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG YOUNG PHENOMS KICK OFF A YEAR OF TRIBUTES TO CHICAGO LEGEND EDDIE HARRIS! NEXTGENJAZZ: FREEDOM JAZZ DANCE FEB 7 AT 7 PM FOSTER PARK 1440 W 84TH ST. HOW MUCH OF A FREE SPIRIT WAS THE LATE, GREAT SAXOPHONIST Eddie Harris? "I love shocking people," he once said. "I'll play `Pop Goes the Weasel' and then suddenly go way out, and people will say, 'Oh man what happened?' and I say, `That'll teach you to program me!'" And in addition to his stylistic adventures onstage, he invented an electric saxophone– and, using a trombone mouthpiece, the "saxobone." His psychedelic jazz was an early forerunner of jazz-rock fusion. He recorded with British rockers Stevie Winwood and Jeff Beck, dabbled in singing (he did a mean Billie Holiday impression) and even performed as a standup comic. (Hear his 1975 album, The Reason Why I'm Talking S--t.) Free jazz? Harris was free in every which way. "He never stays in one spot," said John Scofield. "One minute, he'll be in a groove, and the next minute he'll play something that will just blow you away." Even the vaunted music program at DuSable High School led by Capt. Walter Dyett, which turned out dozens of future jazz greats including Von Freeman, Muhal Richard Kurt Shelby Abrams and Johnny Griffin, couldn't contain Harris. Dyett, he recalled in an interview, "was against anybody playing anything that he didn't tell them to play." He was kicked out of the band twice and transferred to Hyde Park High School for his senior year. -

Keith Rowe New Traditionalism

September 2011 | No. 113 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Keith Rowe New Traditionalism Hal Galper • The Necks • Rastascan • Event Calendar Only those living under rocks not bought during the housing bubble could be unaware of the recent debates going on in the nation’s capital about the country’s economic policies. Maybe some jazz musicians, who know how to stretch a dollar New York@Night and live with crushing financial insecurity, could have helped defuse the crisis. We 4 also have been reporting on the unilateral decision by the National Academy of Interview: Hal Galper Recording Arts and Sciences to remove Latin Jazz from its Grammy Award categories (along with a number of other ‘underperforming’ genres). There have 6 by Ken Dryden been protests, lawsuits and gestures in an attempt to have this policy reversed. Artist Feature: The Necks Though compared to a faltering multi-trillion dollar economy, the latter issue can seem a bit trivial but it still highlights how decisions are made that affect the by Martin Longley 7 populace with little concern for its input. We are curious to gauge our readers’ On The Cover: Keith Rowe opinions on the Grammy scandal. Send us your thoughts at feedback@ by Kurt Gottschalk nycjazzrecord.com and we’ll publish some of the more compelling comments so 9 the debate can have another voice. Encore: Lest We Forget: But back to more pleasant matters: Fall is upon us after a brutal summer 10 (comments on global warming, anyone?). As you emerge from your heat-induced George Barrow Jimmy Raney torpor, we have a full docket of features to transition into long-sleeve weather.