Ears Embiggened: Icons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Chicago Tribune

Colsons return to Chicago with new sounds Adegoke Steve Colson and Iqua Colson bring their experimental music to Constellation on Saturday, Aug. 12, 2017. (Mikel Colson photo) By Howard Reich Chicago Tribune AUGUST 9, 2017, 9:25 AM early 50 years ago, a promising young pianist from New Jersey began studying music at N Northwestern University — and discovered sounds he’d never encountered before. Not so much at school, where classical music predominated, but elsewhere in Evanston and Chicago, where musical revolutions were underway. For just two years before Adegoke Steve Colson came here in 1967, a contingent of fearlessly innovative South Side artists had formed the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a collective that was inventing radical new techniques, concepts and practices for composing and improvising music. Even closer to campus, saxophonist Fred Anderson was making his Birdhouse venue in Evanston a nexus for new music and became an early mentor to Colson. The creative ferment of that period transformed Colson, who will return to Chicago to co-lead a quintet with vocalist Iqua Colson, his wife, Saturday night at Constellation. As he prepares for this engagement, memories of those early days come flooding back. “I remember I saw a flyer for Fred Anderson, because he lived there in Evanston … and we could go by and join his band,” says pianist Colson, who often sat in with the singular improviser. “When I started playing with guys in the AACM. Sometimes (bassist) Fred Hopkins would show up, (drummer) Steve McCall would show up,” adds Colson, who formed a jazz band with fellow student Chico Freeman. -

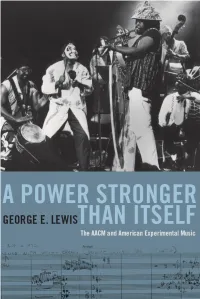

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

Lester Young, Charlie Parker, James Moody, Nat "King" History, but It Was Never Really Appealing

64 Chapter Three The Development of the Experimental Band 65 I would go there to play with my cousins, and I began to learn the names it, then talk about it, and you'd write a little paper on it. This was music of these people- Lester Young, Charlie Parker, James Moody, Nat "King" history, but it was never really appealing. It was nice, but it was so much Cole, Miles Davis. They would be playing this music every time I went nicer to be in the band room hearing that live stuff. there, but I didn't know the name of the music; it was just pretty music. I knew all the singers- the popular music, but I was more drawn to this Mitchell characterizes those who went to DuSable during the Dyett era other music because you just listened, and what you heard was inside as "fortunate," but even Englewood, where he went to high school, had its rather than words and rhythms that they would suggest through the advantages. He began playing baritone saxophone in the high-school band, popular forms. and borrowed an alto saxophone from another student. Jazz was not taught at Englewood, but getting to know the precocious saxophonist Donald In the mid-1950s, Mitchell's family moved briefly to Milwaukee, where "Hippmo" Myrick, who later became associated with both Philip Cobran he started high school and began playing the clarinet. His brother Norman and Earth, Wind, and Fire, made up for that lack. "He kind of took me came to live with the family, bringing along a collection of 78 rpm jazz re under his wing, because he already knew the stuff," said Mitchell. -

Original Music and the Birth of the Aacm

ECSTATIC ENSEMBLE: DESPONT & NUSSBAUM “I don’t stand to benefit when musicians.” Their Chicago headquarters moved frequently, but the format remained constant: everybody is just trying to be like members paid dues to support rentals for everyone else. All of us are highly venues, shared maintenance and promotional duties, and professional musicians were individualized beings, different.” required to teach at the AACM School. –ROSCOE MITCHELL At the time of the AACM's founding in May 1965, Chicago was heavily segregated and its black neighborhoods criminally underserved. There Ecstatic Ensemble: What makes music original? We often use were virtually no opportunities for black “original” to mean unique, but it also refers to composers, and it was rare for black musicians the first, the root, the pattern. For the past five to teach at high levels, join orchestras, or be Original Music decades the Association for the Advancement fairly compensated by local venues and record of Creative Musicians has sought to answer labels. High school teaching jobs were often the this question and produced music that resists only opportunities open to trained musicians, and the Birth of category. Reluctantly labeled jazz, avant-garde, and even those who had achieved widespread classical, electronic—the sonic universe of the success struggled to maintain creative freedom AACM is built on a philosophy of inclusiveness. and fair compensation. “We looked at the lives the AACM of great musicians that were just out there on Known for having produced some of Chicago’s their own, like Charlie Parker,” remembered most renowned musicians and composers such by Catherine Despont Roscoe Mitchell, an original member and widely as Roscoe Mitchell, George Lewis, Joseph and Jake Nussbaum acclaimed saxophonist. -

Keith Rowe New Traditionalism

September 2011 | No. 113 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Keith Rowe New Traditionalism Hal Galper • The Necks • Rastascan • Event Calendar Only those living under rocks not bought during the housing bubble could be unaware of the recent debates going on in the nation’s capital about the country’s economic policies. Maybe some jazz musicians, who know how to stretch a dollar New York@Night and live with crushing financial insecurity, could have helped defuse the crisis. We 4 also have been reporting on the unilateral decision by the National Academy of Interview: Hal Galper Recording Arts and Sciences to remove Latin Jazz from its Grammy Award categories (along with a number of other ‘underperforming’ genres). There have 6 by Ken Dryden been protests, lawsuits and gestures in an attempt to have this policy reversed. Artist Feature: The Necks Though compared to a faltering multi-trillion dollar economy, the latter issue can seem a bit trivial but it still highlights how decisions are made that affect the by Martin Longley 7 populace with little concern for its input. We are curious to gauge our readers’ On The Cover: Keith Rowe opinions on the Grammy scandal. Send us your thoughts at feedback@ by Kurt Gottschalk nycjazzrecord.com and we’ll publish some of the more compelling comments so 9 the debate can have another voice. Encore: Lest We Forget: But back to more pleasant matters: Fall is upon us after a brutal summer 10 (comments on global warming, anyone?). As you emerge from your heat-induced George Barrow Jimmy Raney torpor, we have a full docket of features to transition into long-sleeve weather. -

Artifacts Trio: ...And Then There’S This

ARTIFACTS TRIO: ...AND THEN THERE’S THIS FEBRUARY 27, 2021 5pm We gratefully acknowledge that we operate on the traditional lands of the Tongva, presented by Tataviam, and Chumash peoples—including REDCAT the Gabrieleño, Fernandeño, and Ventureño; members of the Takic and Chumashan Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater language families; and other Indigenous California Institute of the Arts peoples who made their homes in and around the area we now call Los Angeles. ARTIFACTS TRIO: ...AND THEN THERE’S THIS PROGRAM B.K. Steve McCall In Response To Tomeka Reid Blessed Nicole Mitchell I’ll Be Right Here Waiting Steve McCall Song for Helena Tomeka Reid Reflections Nicole Mitchell Pleasure Palace Mike Reed Light on The Path Ed Wilkerson ARTIFACTS TRIO Tomeka Reid, Cello Nicole Mitchell, Flute Mike Reed, Drums “Nicole Mitchell’s flute and Tomeka Reid’s cello met with Mike Reed’s cymbal- heavy drumming to make an aqueous sound that allowed itself to be warped and melted and spread about by the room.” —Giovanni Russonello, The New York Times “The cellist Tomeka Reid, from Chicago, has been one of the great energies of the past year in jazz: a melodic improviser with a natural, flowing sense of song and an experimenter who can create heat and grit with the texture of sound.” —Ben Ratliff, The New York Times “[Nicole Mitchell is] a flutist who embodies the sunny optimism of California and Chicago’s bold, creative spirit.” —Michael J. West, Jazz Times “A multithreat musician who thrives as soloist, bandleader, presenter and global talent scout, [Mike] Reed has emerged as a center of gravity for music in Chicago (and beyond).” —Howard Reich, The Chicago Tribune ABOUT THE PERFORMERS The Artifacts Trio first convened in 2015 in response to the 50th anniversary of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. -

SPIRITUAL DIMENSIONS (Cuneiform Rune 290-291)

Bio information: WADADA LEO SMITH Title: SPIRITUAL DIMENSIONS (Cuneiform Rune 290-291) Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / IMPROVISATION “I decided at the very beginning that Golden Quartet would be a lifelong quartet of mine, no matter what the personnel was or which direction it might go, whether it goes to the Golden Quintet…The idea is that of one horn player and rhythym” – Wadada Leo Smith “...not only as inventive and adventurous as he was when he was a younger player, but his creativity and ability to direct a band into new territory is actually farther reaching than ever before. This is brilliant work.” – All Music Guide “The Golden Quartet is the closest thing to a standard jazz group that Wadada Leo Smith ever used to present his own music. …the music is lively, even explosive at time, yet still exquisitely balanced. …No other composer accommodates the independence of the individual and the unity of the ensemble in quite the way Smith does. …the collective sound always coheres into something purposeful and beautiful. Remarkably, the personalities and forces are kept in balance.”– Point of Departure “...a welcome reminder of Smith's continued importance in the continuum of creative improvised music.” – All About Jazz Lauded as “one of the most vital musicians on the planet” by Coda, Wadada Leo Smith is one of the most visionary, boldly original and artistically important figures in contemporary American jazz and free music, and one of the great trumpet players of our time. -

Barre Phillips Discography

Barre Phillips Discography **ERIC DOLPHY / VINTAGE DOLPHY / GM RECORDINGS /GM3005D NYC: March 14/ April 18 1963 w/ Jim Hall, Phil Woods , Sticks Evans etc... **LEONARD BERNSTEIN - N.Y. PHILARMONIC / LEONARD BERNSTEIN CONDUCTS MUSIC OF OUR TIME. LARRY AUSTIN IMPROVISATIONS FOR ORCHESTRA AND JAZZ SOLISTS. COLUMBIA ML6133 NYC: January 1964 w/ Don Ellis, Joe Cocuzzo **ATTILA ZOLLER / THE HORIZON BEYOND / MERCURY / 13814MCY Berlin : March 15, 1965 w/ Don Friedman, Daniel Humair Note : Mercury 13814 MCY Emarcy MG-26013 **BOB JAMES / EXPLOSIONS / ESP1009 NYC: May 1965 w/ Robert Pozar **ARCHIE SHEPP / NEW THING AT NEWPORT / IMPULSE / A 94 Newport : July 2, 1965 w/ Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Chambers Note : Impulse A94 - Impulse IA9357/2 ** JIMMY GIUFFRE LIVE / EUROPE 1 / 710586 / CB701 Paris, Olympia, 27 February 1965 In trio w/ Don Friedman **ARCHIE SHEPP / ON THIS NIGHT / IMPULSE / A 97 Newport : July 2, 1965 w/ Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Chambers Note : Impulse A97 - Impulse IA9357/2 **PETER NERO / ON TOUR / RCA / LPM3610 Pheonix Arizona, Pueblo and Denver Colorado, February, 1966 w/ Joe Cusatis **ATTILA ZOLLER / KATZ UND MAUS / SABA / 15112ST NYC : December 14-15, 1966 w/ Jimmy Owens **HEINER STATLER / BRAINS ON FIRE VOL 1 / LABOUR RECORDS / LRS7001 - NYC : December , 1966 w/ Jimmy Owens, Garnett Brown, Joe Farrell, Don Fiedman, etc ... **CHRIS MCGREGOR SEXTET - UP TO EARTH - FLEDGING RED 3069 1969/London w/ Louis Mohoto, John Surman, Evan Parker, Mongezi Fezam Dudu Pakwana relased in 2008 - **THE CHRIS McGREGOR TRIO / FLEDGLING RED 3070 London 1969 -

Eric Nemeyer's

Eric Nemeyer’s WWW.JAZZINSIDEMAGAZINE.COM June-July 2018 JAZZ HISTORY FEATURE ArtArt Blakey,Blakey, PartPart 77 Interviews PatPat MartinoMartino Jazz Standard, July 19--22 Famoudou Famoudou DonDon MoyeMoye Comprehensive DirectoryDirectory of NY ClubS, ConcertS OdeanOdean PopePope Spectacular Jazz Gifts - Go To www.JazzMusicDeals.com To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 December 2015 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 1 COVER-2-JI-15-12.pub Wednesday, December 09, 2015 15:43 page 1 MagentaYellowBlacCyank To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 June-July 2018 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 1 Eric Nemeyer’s Jazz Inside Magazine ISSN: 2150-3419 (print) • ISSN 2150-3427 (online) June-July 2018 – Volume 9, Number 4 Cover Photo and photo at right Publisher: Eric Nemeyer Editor: Wendi Li Marketing Director: Cheryl Powers Advertising Sales & Marketing: Eric Nemeyer Circulation: Susan Brodsky Photo Editor: Joe Patitucci Layout and Design: Gail Gentry Contributing Artists: Shelly Rhodes Contributing Photographers: Eric Nemeyer, Ken Weiss Contributing Writers: John Alexander, John R. Barrett, Curtis Daven- port; Alex Henderson; Joe Patitucci; Ken Weiss. ADVERTISING SALES 215-887-8880 Eric Nemeyer – [email protected] ADVERTISING in Jazz Inside™ Magazine (print and online) Jazz Inside™ Magazine provides its advertisers with a unique opportunity to reach a highly specialized and committed jazz readership. Call our Advertising Sales Depart- ment at 215-887-8880 for media kit, rates and information. SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION SUBMITTING PRODUCTS FOR REVIEW Jazz Inside™ (published monthly). To order a subscription, call 215-887-8880 or visit Companies or individuals seeking reviews of their recordings, books, videos, software Jazz Inside on the Internet at www.jazzinsidemagazine.com.