Cuban Jazz in the United States in the Late 1940S Was Closely Interrelated with Bebop’S Speak Popularization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (Guest Post)*

“Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (guest post)* Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie The jazz standard “Manteca” was the product of a collaboration between Charles Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie and Cuban musician, composer and dancer Luciano (Chano) Pozo González. “Manteca” signified one of the beginning steps on the road from Afro-Cuban rhythms to Latin jazz. In the years leading up to 1940, Cuban rhythms and melodies migrated to the United States, while, simultaneously, the sounds of American jazz traveled across the Caribbean. Musicians and audiences acquainted themselves with each other’s musical idioms as they played and danced to rhumba, conga and big-band swing. Anthropologist, dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham was instrumental in bringing several Cuban drummers who performed in authentic style with her dance troupe in New York in the mid-1940s. All this laid the groundwork for the fusion of jazz and Afro-Cuban music that was to occur in New York City in the 1940s, which brought in a completely new musical form to enthusiastic audiences of all kinds. This coming fusion was “in the air.” A brash young group of artists looking to push jazz in fresh directions began to experiment with a radical new approach. Often playing at speeds beyond the skills of most performers, the new sound, “bebop,” became the proving ground for young New York jazz musicians. One of them, “Dizzy” Gillespie, was destined to become a major force in the development of Afro-Cuban or Latin jazz. Gillespie was interested in the complex rhythms played by Cuban orchestras in New York, in particular the hot dance mixture of jazz with Afro-Cuban sounds presented in the early 1940s by Mario Bauzá and Machito’s Afrocubans Orchestra which included singer Graciela’s balmy ballads. -

“Mongo” Santamaría

ABOUT “MONGO” SANTAMARÍA The late 1940's saw the birth of Latin Jazz in New York City, performed first by its pioneers Machito, Mario Bauza, Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo. Ramón "Mongo" Santamaría Rodríguez emerged from the next wave of Latin Jazz that was led by vibraphonist Cal Tjader and timbalero Tito Puente. When Mongo finally became a bandleader himself, his impact was profound on both the Latin music world and the jazz world. His musical career was long, ushering in styles from religious Afro-Cuban drumming and charanga-jazz to pop- jazz, soul-jazz, Latin funk and eventually straight ahead Latin jazz. From Mongo’s bands emerged some young players who eventually became jazz legends, such as Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock and Hubert Laws. I had a chance to meet Mongo a few times during the years which culminated in a wonderful hangout on my radio show Jazz on the Latin Side, broadcast on KJazz 88.1 FM in Los Angeles) where he shared great stories and he also sat in with the live band that I had on the air that night. What a treat for my listeners! After his passing I felt like jazz fans were beginning to forget him. So I decided to form Mongorama in his honor and revisit his innovative charanga-jazz years of the 1960s. Mongo Santamaría was the most impactful Jazz “conguero” ever! Hopefully Mongorama will not only remind jazz fans of his greatness, but also create new fans that will explore his vast musical body of work. Viva Mongo!!!!! - Mongorama founder and bandleader José Rizo . -

Mike Mangini

/.%/&4(2%% 02):%3&2/- -".#0'(0%4$)3*4"%-&34&55*/(4*()54 7). 9!-!(!$25-3 VALUED ATOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/5)& '0$64)*)"5 "$)*&7&5)&$-"44*$ 48*/(406/% "35#-",&: 5)&.&/503 50%%46$)&3."/ 45:-&"/%"/"-:4*4 $2%!-4(%!4%23 Ê / Ê" Ê," Ê/"Ê"6 , /Ê-1 -- (3&(03:)65$)*/40/ 8)&3&+";;41"45"/%'6563&.&&5 #6*-%:06308/ .6-5*1&%"-4&561 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% 5"."4*-7&345"33&.0108&34530,&130-6%8*("5-"4130)"3%8"3&3*.4)05-0$."55/0-"/$:.#"-4 Volume 36, Number 3 • Cover photo by Paul La Raia CONTENTS Paul La Raia Courtesy of Mapex 40 SETTING SIGHTS: CHRIS ADLER Lamb of God’s tireless sticksman embraces his natural lefty tendencies. by Ken Micallef Timothy Saccenti 54 MIKE MANGINI By creating layers of complex rhythms that complement Dream Theater’s epic arrangements, “the new guy” is ushering in a bold and exciting era for the band, its fans, and progressive rock music itself. by Mike Haid 44 GREGORY HUTCHINSON Hutch might just be the jazz drummer’s jazz drummer— historically astute and futuristically minded, with the kind 12 UPDATE of technique, soul, and sophistication that today’s most important artists treasure. • Manraze’s PAUL COOK by Ken Micallef • Jazz Vet JOEL TAYLOR • NRBQ’s CONRAD CHOUCROUN • Rebel Rocker HANK WILLIAMS III Chuck Parker 32 SHOP TALK Create a Stable Multi-Pedal Setup 36 PORTRAITS NYC Pocket Master TONY MASON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Faust’s WERNER “ZAPPI” DIERMAIER One of Three Incredible 70 INFLUENCES: ART BLAKEY Prizes From Yamaha Drums Enter to Win We all know those iconic black-and-white images: Blakey at the Valued $ kit, sweat beads on his forehead, a flash in the eyes, and that at Over 5,700 pg 85 mouth agape—sometimes with the tongue flat out—in pure elation. -

Joseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II: Return

Joseph Jarman’s Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile February 13, 2020 By Cam Scott When composer, priest, poet, and instrumentalist Joseph Jarman passed away in January 2019, a bell sounded in the hearts of thousands of listeners. As an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), as well as its flagship group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarman was a key figure in the articulation of Great Black Music as a multi- generational ethic rather than a standard repertoire. As an ordained Buddhist priest, Jarman’s solicitude transcended philosophical affinity and deepened throughout his life as his music evolved. His musical, poetic, and religious paths appear to have been mutually informative, in spite of a hiatus from public performance in the nineties—and to encounter Jarman’s own words is to understand as much. The full breadth of this complexity is celebrated in the long-awaited reissue of Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile, a blend of smut and sutra, poetry and polemic, that feels like a reaffirmation of Jarman’s ambitious vision in the present day. Black Case wears its context proudly. A near-facsimile of the original 1977 publication by the Art Ensemble of Chicago (which itself was built upon a coil-bound printing from 1974), the volume serves as a time capsule of a key period in the development of an emancipatory musical and cultural program, and an intimate portrait of the artist-as-revolutionary. Black Case, then, feels most contemporary where it is most of its time, as a document of Black militancy and programmatic self-determination in which—to paraphrase Larry Neal’s 1968 summary of the Black Arts Movement—ethics and aesthetics, individual and community, are tightly unified. -

CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program

CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program This patch program is designed to help Girl Scouts of all cultures develop an understanding and appreciation of the culture of Hispanic / Latin Americans through Discover, Connect and Take Action. ¡Bienvenidos! Thanks for your interest in the CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program. You do not need to be an expert or have any previous knowledge on the Hispanic / Latino Culture in order to teach your girls about it. All of the activities include easy-to-follow activity plans complete with discussion guides and lists for needed supplies. The Resource Guide located on page 6 can provide some valuable support and additional information. 1 CHICAS: Discovering Hispanic Heritage Patch Program Requirements Required Activity for ALL levels: Choose a Spanish speaking country and make a brochure or display about the people, culture, land, costumes, traditions, etc. This activity may be done first or as a culminating project. Girl Scout Daisies: Choose one activity from DISCOVER, one from CONNECT and one from TAKE ACTION for a total of FOUR activities. Girl Scout Brownies: Choose one activity from DISCOVER, one from CONNECT and one from TAKE ACTION. Complete one activity from any category for a total of FIVE activities. Girl Scout Juniors: Choose one activity from DISCOVER, one from CONNECT and one from TAKE ACTION. Complete two activities from any category for a total of SIX activities. Girl Scout Cadettes, Seniors and Ambassadors: Choose two activities from DISCOVER, two from CONNECT and two from TAKE ACTION. Then, complete the REFLECTION activity, for a total of SEVEN activities. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin

THE SYNTHESIS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL STYLES IN THREE PIANO WORKS OF NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN __________________________________________________ A monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS __________________________________________________________ by Tatiana Abramova August 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Charles Abramovic, Advisory Chair, Professor of Piano Harvey Wedeen, Professor of Piano Dr. Cynthia Folio, Professor of Music Studies Richard Oatts, External Member, Professor, Artistic Director of Jazz Studies ABSTRACT The Synthesis of Jazz and Classical Styles in Three Piano Works of Nikolai Kapustin Tatiana Abramova Doctor of Musical Arts Temple University, 2014 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Charles Abramovic The music of the Russian-Ukrainian composer Nikolai Kapustin is a fascinating synthesis of jazz and classical idioms. Kapustin has explored many existing traditional classical forms in conjunction with jazz. Among his works are: 20 piano sonatas, Suite in the Old Style, Op.28, preludes, etudes, variations, and six piano concerti. The most significant work in this regard is a cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 82, which was completed in 1997. He has also written numerous works for different instrumental ensembles and for orchestra. Well-known artists, such as Steven Osborn and Marc-Andre Hamelin have made a great contribution by recording Kapustin's music with Hyperion, one of the major recording companies. Being a brilliant pianist himself, Nikolai Kapustin has also released numerous recordings of his own music. Nikolai Kapustin was born in 1937 in Ukraine. He started his musical career as a classical pianist. In 1961 he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory, studying with the legendary pedagogue, Professor of Moscow Conservatory Alexander Goldenweiser, one of the greatest founders of the Russian piano school. -

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131 Instructor: Madison Heying Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Course Description: This course is a survey of the history and literature of electronic music. In each class we will learn about a music-making technique, composer, aesthetic movement, and the associated repertoire. Tests and Quizzes: There will be one test for this course. Students will be tested on the required listening and materials covered in lectures. To be prepared students must spend time outside class listening to required listening, and should keep track of the content of the lectures to study. Assignments and Participation: A portion of each class will be spent learning the techniques of electronic and computer music-making. Your attendance and participation in this portion of the class is imperative, since you will not necessarily be tested on the material that you learn. However, participation in the assignments and workshops will help you on the test and will provide you with some of the skills and context for your final projects. Assignment 1: Listening Assignment (Due June 30th) Assignment 2: Field Recording (Due July 12th) Final Project: The final project is the most important aspect of this course. The following descriptions are intentionally open-ended so that you can pursue a project that is of interest to you; however, it is imperative that your project must be connected to the materials discussed in class. You must do a 10-20 minute in class presentation of your project. You must meet with me at least once to discuss your paper and submit a ½ page proposal for your project. -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

JREV3.8FULL.Pdf

JAZZ WRITING? I am one of Mr. Turley's "few people" who follow The New Yorker and are jazz lovers, and I find in Whitney Bal- liett's writing some of the sharpest and best jazz criticism in the field. He has not been duped with "funk" in its pseudo-gospel hard-boppish world, or- with the banal playing and writing of some of the "cool school" Californians. He does believe, and rightly so, that a fine jazz performance erases the bound• aries of jazz "movements" or fads. He seems to be able to spot insincerity in any phalanx of jazz musicians. And he has yet to be blinded by the name of a "great"; his recent column on Bil- lie Holiday is the most clear-headed analysis I have seen, free of the fan- magazine hero-worship which seems to have been the order of the day in the trade. It is true that a great singer has passed away, but it does the late Miss Holiday's reputation no good not to ad• LETTERS mit that some of her later efforts were (dare I say it?) not up to her earlier work in quality. But I digress. In Mr. Balliett's case, his ability as a critic is added to his admitted "skill with words" (Turley). He is making a sincere effort to write rather than play jazz; to improvise with words,, rather than notes. A jazz fan, in order to "dig" a given solo, unwittingly knows a little about the equipment: the tune being improvised to, the chord struc• ture, the mechanics of the instrument, etc. -

World of Jazz

EXPERIENCE THE World of Jazz JANUARY Berklee High School Jazz Festival | Boston, MA, USA The Berklee High School Jazz Festival is the largest festival of its kind in the United States and is held annually every January in Boston, Massachusetts! Jazz ensembles and combos compete during the day, are adjudicated by Berklee’s top faculty and will receive a written critique of their performance. Ask us about additional performance opportunities in Boston for jazz ensembles! festival.berkleejazz.org FEBRUARY Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival | Moscow, Idaho, USA Under the artistic direction of John Clayton, this festival dates back to 1967 and has since expanded to be one of the largest jazz festivals in the Western part of the United States. Thousands of middle school, high school and collegiate students travel to small town Moscow, Idaho every year to participate in the adjudicated sessions, daily workshops and evening performances featuring professional artists! www.uidaho.edu/jazzfest MARCH Cape Town International Jazz Festival | Cape Town, South Africa This amazing musical event takes place annually at the Cape Town International Convention Centre and is the largest musical event in sub-Saharan Africa! Utilizing 5 venues, over 40 artists perform during the 2-night event with nearly 40,000 visitors in attendance. The program usually includes an even split between South African and other international artists, giving it a unique local flair. www.capetownjazzfest.com APRIL Jazzkaar | Tallinn, Estonia Experience the beauty of the Baltics during this annual 10-day jazz festival in Estonia’s capital, Tallinn! With over a couple dozen venues, there’s plenty of performances to attend and with artists like Bobby McFerrin, Chick Corea and Jan Garbarek, who can resist? www.jazzkaar.ee/en MAY Brussels Jazz Marathon | Brussels, Belgium Belgium’s history of jazz really begins with Mr. -

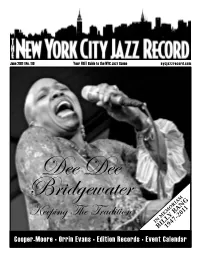

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty.