Chicago Music Communities and the Everyday Significance of Playing Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duke Ellington Monument Unveiled in Central Park Tatum, Elinor

Document 1 of 1 Duke Ellington monument unveiled in Central Park Tatum, Elinor. New York Amsterdam News [New York, N.Y] 05 July 1997: 14:3. Abstract A monument to jazz legend Duke Ellington was unveiled at Duke Ellington Circle on the northeast corner of Central Park on Jul 1, 1997. The jet black, 25-ft-high memorial was sculpted by Robert Graham and depicts Ellington, standing by his piano. The statue is a gift from the Duke Ellington Memorial Fund, founded by Bobby Short. Full Text Duke Ellington monument unveiled in Central Park The four corners of Central Park are places of honor. On the southwest gateway to the park are monuments and a statue of Christopher Columbus. On the southeast corner is a statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman. Now, on the northeast corner of the park, one of the greatest jazz legends of all time and a Harlem hero, the great Duke Ellington, stands firmly with his piano and his nine muses to guard the entrance to the park and to Harlem from now until eternity. The monument to Duke Ellington was over 18 years in the making, and finally, the dream of Bobby Short, the founder of the Duke Ellington Memorial Fund, came to its fruition with the unveiling ceremony at Duke Ellington Circle on 110th Street and Fifth Avenue on Tuesday. Hundreds of fans, family, friends and dignitaries came out to celebrate the life of Duke Ellington as he took his place of honor at the corner of Central Park. The jet black, 25-foot-high memorial sculpted by Robert Graham stands high in the sky, with Ellington standing by his piano, supported by three pillars of three muses each. -

Chicago Jazz Philharmonic’S “Scenes from Life: Cuba!” Friday, Nov

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Jill Evans La Penna James Juliano SHOUT Marketing & Media Relations [email protected] • [email protected] (312) 533-9119 • (773) 852-0506 THE AUDITORIUM THEATRE PRESENTS THE UNITED STATES PREMIERE OF ORBERT DAVIS’ CHICAGO JAZZ PHILHARMONIC’S “SCENES FROM LIFE: CUBA!” FRIDAY, NOV. 13 Musicians and Members of a Cuban Delegation Join the CJP for this Historic One Night Only Event on the Landmark Auditorium Stage CHICAGO, IL — The Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University is proud to announce the United States premiere of “Scenes from Life: Cuba!” composed and conducted by Orbert Davis and performed by his Chicago Jazz Philharmonic (CJP), Friday, Nov. 13 at 7:30 p.m. at the Auditorium Theatre, 50 E. Congress Parkway. Featured guest artists for this extraordinary performance will include student musicians from Cuba’s national conservatory of the arts. Tickets are $29 - $68 and are available at AuditoriumTheatre.org, by calling (312) 341-2300 or in-person at the Auditorium Theatre’s Box Office, 50 E. Congress Parkway. Subscriptions for the Auditorium Theatre’s 2015 - 2016 season and discounted tickets for groups of 10 or more are also available. For more information visit AuditoriumTheatre.org. “For over 125 years, the Auditorium Theatre has witnessed historic events that included presidents, renowned performers, world-famous arts companies and more. This United States premiere, featuring musicians from Cuba, is another historic moment to celebrate,” said Executive Director Brett Batterson. “Orbert and the Chicago Jazz Philharmonic were witnesses to the earliest days of our country’s new relationship with Cuba and will bring those emotions, as well as the rich history of Cuba’s music, to the Auditorium for an extraordinary performance.” In December 2014, Davis and Chicago Jazz Philharmonic musicians conducted a weeklong residency at Universidad de las Artes (ISA), Cuba’s national conservatory of music in Havana, culminating in the debut of this new work at the Havana International Jazz Festival. -

Oral History T-0001 Interviewees: Chick Finney and Martin Luther Mackay Interviewer: Irene Cortinovis Jazzman Project April 6, 1971

ORAL HISTORY T-0001 INTERVIEWEES: CHICK FINNEY AND MARTIN LUTHER MACKAY INTERVIEWER: IRENE CORTINOVIS JAZZMAN PROJECT APRIL 6, 1971 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Today is April 6, 1971 and this is Irene Cortinovis of the Archives of the University of Missouri. I have with me today Mr. Chick Finney and Mr. Martin L. MacKay who have agreed to make a tape recording with me for our Oral History Section. They are musicians from St. Louis of long standing and we are going to talk today about their early lives and also about their experiences on the music scene in St. Louis. CORTINOVIS: First, I'll ask you a few questions, gentlemen. Did you ever play on any of the Mississippi riverboats, the J.S, The St. Paul or the President? FINNEY: I never did play on any of those name boats, any of those that you just named, Mrs. Cortinovis, but I was a member of the St. Louis Crackerjacks and we played on kind of an unknown boat that went down the river to Cincinnati and parts of Kentucky. But I just can't think of the name of the boat, because it was a small boat. Do you need the name of the boat? CORTINOVIS: No. I don't need the name of the boat. FINNEY: Mrs. Cortinovis, this is Martin McKay who is a name drummer who played with all the big bands from Count Basie to Duke Ellington. -

Sendung, Sendedatum

WDR 3 Jazz & World, 24. Februar 2018 Persönlich mit Götz Alsmann 13:04-15:00 Stand: 23. Februar 2018 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de Moderation: Götz Alsmann Redaktion: Bernd Hoffmann 22:04-24:00 Laufplan 1. Tempo’s Tempo K/T: Nino Tempo 2:33 NINO TEMPO NCB 1050 LP: The Girl Can’t Help It 2. Sweet And Lovely K/T: Gus Arnheim/ Nappy Lemare 4:25 COLEMAN HAWKINS Pablo 2310890; LC: 03254 LP: Jazz Dance 3. Why Was I Born K/T: Jerome Kern/ Oscar Hammerstein 8:25 GENE AMMONS & Verve 2578; LC: 00383 SONNY STITT LP: Boss Tenors In Orbit 4. Wheel of Fortune K/T: Benny Benjamin/ George Davis Weiss 2:50 THE FOUR FLAMES Specialty 423 Single 5. Le Papillon K/T: Edvard Grieg 2:57 CLAUDE THORNHILL Circle 19 CD: Claude Thornhill 1941 & 1947 6. Träumerei K/T: Robert Schumann 2:12 CLAUDE THORNHILL wie Titel 5 7. Robbins’ Nest K/T: Sir Charles Thompson 3:59 CLAUDE THRONHILL Hindsight 108; LC: 00171 LP: The Uncollected Claude Thornhill 1947 8. Just About This Time K/T: LouisPrima/ PaulCunningham/ 3:59 Last Night Sidney Miller CLAUDE THORNHILL wie Titel 7 9. Love Me Love K/T: Wolfe /Lee 2:30 FRAN WARREN MGM 3394; LC: 00383 LP: Mood Indigo 10. Donna Lee K/T: Charlie Parker 2:27 CLAUDE THORNHILL wie Titel 7 11. Penthouse Serenade K/T: Val Burton/ Will Jason 2:45 HELEN O’CONNELL Hindsight 228; LC: 00171 LP: The Uncollected Helen O’Connell 1953 Dieses Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The oiceV of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Recommended Citation Searcy, Jennifer, "The oV ice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago" (2012). Dissertations. Paper 688. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/688 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Jennifer Searcy LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE VOICE OF THE NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN RADIO, WVON, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY/PUBLIC HISTORY BY JENNIFER SEARCY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Jennifer Searcy, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their feedback throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. As the chair, Dr. Christopher Manning provided critical insights and commentary which I hope has not only made me a better historian, but a better writer as well. -

Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": an Analytical Approach to Jazz

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Nicholas Vincent, "Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARLES RUGGIERO’S “TENOR ATTITUDES”: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH TO JAZZ STYLES AND INFLUENCES A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2009 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my wife Pagean: without you, I could not be where I am today. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout the writing and revising of this document. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Griffin Campbell and Dr. Willis Delony for their tireless work with and belief in me over the past three years, as well as past professors Dr. -

Culturalupdate

CONCIERGE UNLIMITED INTERNATIONAL July 2016 culturalupdate Volume XXVI—Issue VII “Fireworks and temperatures are exploding!” Did You Know? ♦Independence Day♦Beach Getaways♦Festivals♦and more♦ The Wrigley Building was the first air-conditioned office building in Chicago! New/News Arts/Museums ♦Bad Hunter (802 W. Randolph, Chicago) Opens 2 Witness MCA Chicago Bad Hunter is coming to the West Loop. Slated to 15 Copying Delacroix’s Big Cats Art Institute Chicago open in late summer, Bad Hunter will specialize 15 Post Black Folk Art in America Center for Outsider Art in meats fired up on a wooden grill, along with a 16 The Making of a Fugitive MCA Chicago lower-alcohol cocktail menu. 26 Andrew Yang MCA Chicago ♦The Terrace At Trump (401 N. Wabash, Chicago) Through 3 Materials Inside and Out Art Institute Chicago The Terrace At Trump just completed 3 Diane Simpson MCA Chicago renovations on their rooftop! Enjoy a 10 Eighth BlackBird Residency MCA Chicago signature cocktail with stellar views and 11 The Inspired Chinese Brush Art Institute Chicago walk away impressed! 17 La Paz Hyde Park Art Center 17 Botany of Desire Hyde Park Art Center ♦Rush Hour Concerts at St. James Cathedral (65 E. Huron) 17 Steve Moseley Patience Bottles Center for Outsider Art Forget about sitting in traffic or running to your destination. Enjoy 18 Antiquaries of England Art Institute Chicago FREE rush hour concerts at St. James Cathedral Tuesday’s in July! Ongoing ♦5th: Russian Romantic Arensky Piano Trio No. 1 What is a Planet Adler Planetarium ♦12th: Debroah Sobol -

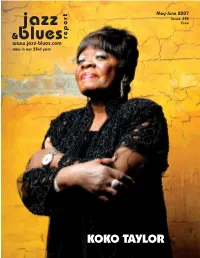

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Johnny Pate

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Johnny Pate Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Pate, Johnny Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Johnny Pate, Dates: September 30, 2004 Bulk Dates: 2004 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:29:11). Description: Abstract: Jazz bassist and music arranger Johnny Pate (1923 - ) formed the Johnny Pate Trio and Combo, and was house bassist for Chicago’s The Blue Note. Johnny Pate’s bass solo on “Satin Doll” is featured on the album "Duke Ellington Live at The Blue Note," and he has collaborated with Curtis Mayfield, produced the Impressions’s hits “Amen,” “We’re A Winner” and “Keep On Pushin’.” and arranged for B.B. King, Gene Chandler and Jerry Butler. Pate was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 30, 2004, in Las Vegas, Nevada. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2004_188 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Jazz bassist, rhythm and blues arranger John W. Pate, Sr., “Johnny Pate,” was born December 5, 1923 in blue collar Chicago Heights, Illinois. Pate took an interest in the family’s upright piano and learned from the church organist who boarded with them. He attended Lincoln Elementary School, Washington Junior High and graduated from Bloom Township High School in 1942. Drafted into the United graduated from Bloom Township High School in 1942. Drafted into the United States Army, Pate joined the 218th AGF Army Band where he took up the tuba and played the upright bass in the jazz orchestra. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1991, Tanglewood

/JQL-EWOOD . , . ., An Enduring Tradition ofExcellence In science as in the lively arts, fine performance is crafted with aptitude attitude and application Qualities that remain timeless . As a worldwide technology leader, GE Plastics remains committed to better the best in engineering polymers silicones, superabrasives and circuit board substrates It's a quality commitment our people share Everyone. Every day. Everywhere, GE Plastics .-: : ;: ; \V:. :\-/V.' .;p:i-f bhubuhh Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Grant Llewellyn and Robert Spano, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Tenth Season, 1990-91 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President T Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, V ice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Mrs. R. Douglas Hall III Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Francis W. Hatch Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Julian T. Houston Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett R. Willis Leith, Jr. Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Philip K. Allen Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George Lee Sargent Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr.