Pat Patrick Interstellar Low Ways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saturn Is Both the Name of Sun Ra's Record Label and the Place That He Claimed As Home, Even Though a More Earthly Account W

Contact: Glenn Siegel, (413) 545-2876 www.fineartscenter.com/magictriangle THE 2004 MAGIC TRIANGLE JAZZ SERIES PRESENTS: Sun Ra Arkestra under the direction of Marshall Allen The Magic Triangle Jazz Series, produced by WMUA, 91.1FM and the Residential Arts Program of the Fine Arts Center at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, continues its 15th season with a performance by Sun Ra Arkestra under the direction of Marshall Allen, featuring Michael Ray, Fred Adams, David Gordon- trumpets; Tyrone Hill, Dave Davis, Dick Griffin-trombones; Marshall Allen, Noël Scott, Ya Ya Abdul Majid, Charles Davis-reeds; Bruce Edwards-electric guitar; John Ore-bass; Luqman Ali, Elson Nascimento, Jimmi Esspirit-percussion on Thursday, March 25, 2004 at Bezanson Recital Hall, University of Massachusetts, Amherst at 8:00 pm. Saturn is both the name of Sun Ra's record label and the place that he claimed as home, even though a more earthly account would have his birthplace (22 May 1914) and resting place (30 May 1993) as Birmingham, Alabama. Composer, arranger, keyboard master and philosophical guru (and Trickster), Le Sony'Ra became an internationally acclaimed exponent of free jazz, a leader in retro-swing and a continuing source of breath-taking originality in the music that we call jazz. Born May 25, 1924 in Louisville, Kentucky, Marshall Allen was stationed in Paris during WW II, and played in Europe with Don Byas and James Moody during the late 40's. Upon his discharge, Mr. Allen enrolled in the Paris Conservatory of Music studying clarinet. Returning to the States in 1951 Marshall settled in Chicago where he met Sun Ra. -

Booker Little

1 The TRUMPET of BOOKER LITTLE Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 11, 2020 2 Born: Memphis, April 2, 1938 Died: NYC. Oct. 5, 1961 Introduction: You may not believe this, but the vintage Oslo Jazz Circle, firmly founded on the swinging thirties, was very interested in the modern trends represented by Eric Dolphy and through him, was introduced to the magnificent trumpet playing by the young Booker Little. Even those sceptical in the beginning gave in and agreed that here was something very special. History: Born into a musical family and played clarinet for a few months before taking up the trumpet at the age of 12; he took part in jam sessions with Phineas Newborn while still in his teens. Graduated from Manassas High School. While attending the Chicago Conservatory (1956-58) he played with Johnny Griffin and Walter Perkins’s group MJT+3; he then played with Max Roach (June 1958 to February 1959), worked as a freelancer in New York with, among others, Mal Waldron, and from February 1960 worked again with Roach. With Eric Dolphy he took part in the recording of John Coltrane’s album “Africa Brass” (1961) and led a quintet at the Five Spot in New York in July 1961. Booker Little’s playing was characterized by an open, gentle tone, a breathy attack on individual notes, a nd a subtle vibrato. His soli had the brisk tempi, wide range, and clean lines of hard bop, but he also enlarged his musical vocabulary by making sophisticated use of dissonance, which, especially in his collaborations with Dolphy, brought his playing close to free jazz. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

4823C7a9d589da82e72837249d

RETURN TO THE EAST BROOKLYN RECLRIMS THE BLRCK RRT FORM KNOWN RS JRZZ I' IIlII£I SCIIII£I • B9 BllSIl MCHBII 'What you're about to hear is not jazz, or some other irrelevant term we allow others 10 use in defining our creation, but the sounds thai are about to saturate your being and serlsitize your soul is the continuing process of nationalist consciousness manifesting its message within the conlext of one of our strongest natural resources: Black music. What is represented on these jams is the crystallization of the role of Black music as a functional organ in the struggle for national liberation.. AJkebu-lan is the unfolding of this progress as mu!>ic-meaoing. It is sound-feeling." KwmbI. >PUI<Irc .... -_. on SUN-Uol his lpOkrn.word innoduuion amounl$ 10 :l m:o.ni- Kwasi Konadu'l r«mt book, Trulh Cru.sJKJ It> tIN &nh rrd:o.iming tlK Black nl form known u WiU RiM Api.., is the delining tome on lhe Ezsr.. h details T for uS/: ali :o.libn:aling. II2l1"P"rti..., vdlic:k. '1M do- lhecompln worIrinV ofhow the organiulion flourished for qurnl <kKript ion ofil :oJ :l -funuion,,1 organ- ckserillQ 1M o>'n adead... 1hc wt and iu primary k>c:o.tion at ,00aver mk of$('lUnd wilhin m.- Ezsr. organiu.ion wdl. MllSic Plac:c in Brooklyn WU n(K just a norefrom or musk hall, bul the blood pumping, mako i. as;"r m dig"". and a w::o.yoflifc.lhc Uhunf Food asan or. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

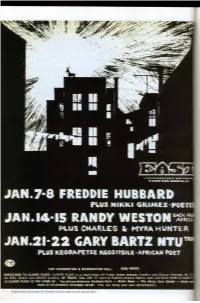

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

S·Ylo )Oll,J SCHOOL of MUSIC 11- I~ UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON Presents

( (t tN1 ~?t (t ol r.s L S·Ylo )Oll,J SCHOOL OF MUSIC 11- I~ UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON presents featuring Seattle's own Sun Ra Tribute Band Jones Playhouse, 18 November 2014 (!. ])=1f Ir,09'1 Performed without intermission, the set includes Saturn, Lights ofa Satellite, Carefree, Space Loneliness, Somewhere Else, Others in Their World, Outer Nothingness, A Call for All Demons, We Travel the Spaceways, costumes, improvisations, processionals and other surprises. Artist Biography by Scott Yanow Of all the jazz musicians, Sun Ra was probably the most controversial. He did not make it easy for people to take him seriously, for he surrounded his adventurous music with costumes and mythology that both looked backward toward ancient Egypt and forward into science fiction. In addition, Ra documented his musk in very erratic fashion on-hjs-SaQ.im label, gel}er1l.!.ly not listing recording dates and giving inaccurat~ personnel information, so one could not really tell how adv'anced some 'of his innovations were. It has taken a lot of time to sort it all out (although Robert L. CampbeU's Sun Ra discography has done a miraculous job). In addition, while there were times when Sun Ra's aggregation performed brilliantly, on other occasions they were badly out of tune and showcasing absurd vocals. Near the end of his life, Ra was featuring plate twirlers and fire eaters in his colorful show as a sort of Ed Sullivan for the 1980s. But despite all of the trappings, Sun Ra was a major innovator. Bom Herman Sonny Blount in Birmingham, AL (although he claimed he was from another planet), Ra led his own band for the first time in 1934. -

Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 "The planet is the way it is because of the scheme of words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1086 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] "THE PLANET IS THE WAY IT IS BECAUSE OF THE SCHEME OF WORDS": SUN RA AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RECKONING BY MARYAM IVETTE PARHIZKAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York. 2015 i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Thesis Adviser: ________________________________________ Ammiel Alcalay Date: ________________________________________ Executive Officer: _______________________________________ Matthew K. Gold Date: ________________________________________ THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract "The Planet is the Way it is Because of the Scheme of Words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning By Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Adviser: Ammiel Alcalay This constellatory essay is a study of the African American sound experimentalist, thinker and self-proclaimed extraterrestrial Sun Ra (1914-1993) through samplings of his wide, interdisciplinary archive: photographs, film excerpts, selected recordings, and various interviews and anecdotes. -

Chicago Jazz Visionaries Mike Reed and Jason Adasiewicz Perform Musical Alchemy in New Myth/Old Science, Transforming Discarde

Bio information: LIVING BY LANTERNS Title: NEW MYTH/OLD SCIENCE (Cuneiform Rune 345) Format: CD / LP Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / AVANT-JAZZ Chicago Jazz Visionaries Mike Reed and Jason Adasiewicz Perform Musical Alchemy in New Myth/Old Science, Transforming Discarded Sun Ra Rehearsal Tape Into Improvisational Gold with their group Living By Lanterns, An All-Star Nine-Piece Ensemble, Featuring a Mighty Cast of Young Chicago & New York Masters According to some versions of String Theory, ours is but one of an infinite number of universes. But you would need to dig deeply into the cosmological haystack before encountering a project as extraordinary and unlikely as New Myth/Old Science, which brings together an incandescent cast of Chicago and New York improvisers to explore music inspired by a previously unknown recording of Sun Ra. In the hands of drummer Mike Reed and vibraphonist Jason Adasiewicz, who are both invaluable and protean creative forces on Chicago’s vibrant new music scene, Ra’s informal musings serve as a portal for their cohesive but multi-dimensional combo, newly christened Living By Lanterns. Commissioned by Experimental Sound Studio (ESS), the music is one of several projects created in response to material contained in ESS’s vast Sun Ra/El Saturn Audio Archive. Rather than a Sun Ra tribute, Reed and Adasiewicz have crafted a melodically rich, harmonically expansive body of themes orchestrated from fragments extracted from a rehearsal tape marked “NY 1961,” featuring Ra on electric piano, John Gilmore on tenor sax and flute, and Ronnie Boykins on bass. -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz.