Hljfgtives Jlepont on Tnlp to P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Watching Brief Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of AREU and European Union. Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-34-1 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1905 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 Table of Contents About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit .................................................... II Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Past Experiences in Sedentarisation .......................................................................... 2 Sedentarisation Post-2001 ...................................................................................... 3 Drivers of Sedentarisation ......................................................................................... -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

AFGHANISTAN Logar Province

AFGHANISTAN Logar Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Logar Province Reference Map 69°0'0"E 69°30'0"E Jalrez Paghman Legend District Kabul District District Bagrami ^! Capital Maydanshahr District District !! Provincial Center ! District Center ! Chaharasyab Musayi Surobi !! Chaharasyab District Administrative Boundaries Maydanshahr District District Nerkh Musayi ! ! Khak-e-Jabbar International ! Province Kabul Hesarak Distirict Wa rd ak Province District Transportation Province Khak-e-Jabbar Hesarak District Nangarhar ! Primary Road Province Secondary Road o Airport Chak Nerkh District District p Airfield Mohammadagha ! Mohammadagha River/Stream District River/Lake p Azra ! Azra Logar District Province Khoshi Pul-e-Alam Alikhel ! Saydabad Khoshi ! District !! (Jaji) Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM 34°0'0"N 34°0'0"N District Barakibarak ! Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI Pul-e-Alam Alikhel Schools - Ministry of Education District (Jaji) ! ° ! Fata Health Facilities - Ministry of Health Kurram Barakibarak Agency Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Saydabad District District 0 20 Kms Dand Wa Patan Lija District Ahmad Disclaimers: Khel The designations employed and the presentation of material ! Chamkani on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion District Charkh whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Chamkani District Paktya ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation ! Charkh Province Lija Ahmad Khel of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad-settler conflict in Afghanistan today Dr. Antonio Giustozzi October 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Synthesis paper Nomad-settler conflict in Afghanistan today Dr. Antonio Giustozzi October 2019 Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-40-2 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1907 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research institute based in Kabul that was established in 2002 by the assistance of the international community in Afghanistan. AREU’s mission is to inform and influence policy and practice by conducting high-quality, policy relevant, evidence-based research and actively disseminating the results and promote a culture of research and learning. As the top think-tank in Afghanistan and number five in Central Asia according to the Global Go To Think Tank Index Report at the University of Pennsylvania, AREU achieves its mission by engaging with policy makers, civil society, researchers and academics to promote their use of AREU’s research-based publications and its library, strengthening their research capacity and creating opportunities for analysis, reflection and debate. AREU is governed by a Board of Directors comprised of representatives of donor organizations, embassies, the United Nations and other multilateral agencies, Afghan civil society and independent experts. -

Civilian Casualties Were Due to the Airstrikes and Night Raids, As Well As Roadside Bomb Explosions

0 ISSUE No: 11 (July 19 – 25, 2019) War Casualties’ Weekly Report www.qased.org QASED Strategic Research Center closely monitors - the casualties of Afghan civilians and the involved [email protected] parties due to war and security incidents on a weekly basis. The casualties’ figures are collected based on 077 281 58 58 confirmed information and reports reported by the Afghan government sources, Taliban sources, eye-witnesses, and other reliable sources. The main purpose of these reports is to grab attention of authorities and responsible parties to severe casualties of the ongoing war. 1 Preface This report covers the casualties of security incidents in the country, which have been occurred during 19 – 25 July 2019. Last week's report shows that the casualties of both sides and civilians decreased compared to the previous week. The deadliest incident for Afghan forces took place in Ashkamish district of Takhar province, in which at least 37 Afghan soldiers were killed and 6 others wounded. Meanwhile, most of the civilian casualties were due to the airstrikes and night raids, as well as roadside bomb explosions. Going forward through the report, details and exact figures of the casualties’ of the Afghan government forces, anti-government armed militants and civilians can be found in separate titles. Afghan Forces’ Casualties Last week, Afghan forces have been killed and wounded due to Taliban attacks, face-to-face battles and explosions: July 19: A local policeman has been killed and two others injured due to a roadside bomb explosion in Chaparhar district of Nangarhar province. A police officer has been killed in a Taliban attack in PD1 of Kunduz city. -

Knowledge on Fire: Attacks on Education in Afghanistan Risks and Measures for Successful Mitigation

Knowledge on Fire: Attacks on Education in Afghanistan Risks and Measures for Successful Mitigation September 2009 CARE International in Afghanistan and the Afghan Ministry of Education gratefully acknowledge the financial, technical, and moral support of the World Bank as the initiator and champion of this study, and in particular, Asta Olesen and Joel Reyes, two dedicated members of the Bank’s South Asia regional Team. We would further like to thank all of the respondents who gave of their time, effort, and wisdom to help us better understand the phenomenon of attacks on schools in Afghanistan and what we may be able to do to stop it. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Author: Marit Glad Assistants: Massoud Kohistani and Abdul Samey Belal Desk research, elaboration of tools and trainings of survey team: Waleed Hakim. Data collection: Coordination of Afghan Relief/Organization for Sustainable Development and Research (CoAR/OSDR). This study was conducted by CARE on behalf of the World Bank and the Ministry of Education, with the assistance of CoAR/OSDR. Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary.................................................................................................. 1 2 Introduction............................................................................................................... 6 2.1 HISTORY..............................................................................................................................7 -

Afghanistan Rule of Law Project

AFGHANISTAN RULE OF LAW PROJECT FIELD STUDY OF INFORMAL AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE IN AFGHANISTAN AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON IMPROVING ACCESS TO JUSTICE AND RELATIONS BETWEEN FORMAL COURTS AND INFORMAL BODIES Contracted under USAID Contract Number: DFD-I-00-04-00170-00 Task Order Number: DFD-1-800-00-04-00170-00 Afghanistan Rule of Law Project Checchi and Company Consulting, Inc. Afghanistan Rule of Law Project House #959, St. 6 Taimani iWatt Kabul, Afghanistan Corporate Office: 1899 L Street, NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA June 2005 This publication was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY METHODOLOGY .............................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF INFORMAL AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE.......................................4 A. Definition and Characteristics..........................................................................................................4 B. Recent Studies...................................................................................................................................6 C. Jirga and Shura..................................................................................................................................7 III. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS............................................................9 A. The Informal System ........................................................................................................................9 B. The Formal System.........................................................................................................................12 -

Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:01/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABBASIN 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifiying Information):Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we- work/Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. Name 6: ABDUL AHAD 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifiying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. -

Name (Original Script): ﻦﯿﺳﺎﺒﻋ ﺰﻳﺰﻌﻟا ﺪﺒﻋ ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ

Sanctions List Last updated on: 2 October 2015 Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List Generated on: 2 October 2015 Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found on the Committee's website at: http://www.un.org/sc/committees/dfp.shtml A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. QDi.012 Name: 1: NASHWAN 2: ABD AL-RAZZAQ 3: ABD AL-BAQI 4: na ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺒﺎﻗﻲ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1961 POB: Mosul, Iraq Good quality a.k.a.: a) Abdal Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi b) Abd Al- Hadi Al-Iraqi Low quality a.k.a.: Abu Abdallah Nationality: Iraqi Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 6 Oct. 2001 (amended on 14 May 2007, 27 Jul. -

IN SEARCH of ANSWERS: U.S. Military Investigations and Civilian Harm

IN SEARCH OF ANSWERS: U.S. Military Investigations and Civilian Harm 1 Cover photo www.civiliansinconflict.org Sgt. Shawn Miller, February 2, 2011 www.law.columbia.edu/human-rights-institute Report designed by Dena Verdesca. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) is an international organization dedicated to promoting the protection of civilians caught in conflict. CIVIC’s mission is to work with armed actors and civilians in conflict to develop and implement solutions to prevent, mitigate, and respond to civilian harm. Our vision is a world where parties to armed conflict recognize the dignity and rights of civilians, prevent civilian harm, protect civilians caught in conflict, and amend harm. CIVIC was established in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a young humanitarian who advocated on behalf of civilian war victims and their families in Iraq and Afghanistan. Building on her extraordinary legacy, CIVIC now operates in conflict zones throughout the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and South Asia to advance a higher standard of protection for civilians. At CIVIC, we believe that parties to armed conflict have a responsibility to prevent and address civilian harm. We assess the causes of civilian harm in particular conflicts, craft practical solutions to address that harm, and advocate the adoption of new policies and practices that lead to the improved wellbeing of civilians caught in conflict. Recognizing the power of collaboration, we engage with civilians, governments, militaries, and international and regional institutions to identify, institutionalize, and strengthen protections for civilians in conflict. www.civiliansinconflict.org The Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute advances international human rights through education, advocacy, fact-finding, research, scholarship, and critical reflection. -

AFGHANISTAN MONTHLY IDP UPDATE for AUGUST 2014 01 – 31 August 2014

AFGHANISTAN MONTHLY IDP UPDATE FOR AUGUST 2014 01 – 31 August 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS ---------------------------------------------------- 19,862 people displaced by Regional monthly/cumulative IDP Statistics conflict were profiled during The major causes August 2014, of whom of displacements 12,938 individuals were were cited as Region end-Jul 2014 Increase Decrease end-Aug 2014 displaced in August, 5,008 in armed conflict between Afghan July, 1,064 in June and 852 National Security South 198,568 4,312 - 202,880 earlier. Forces (ANSF) and West 185,629 2,218 - 187,847 The total number of profiled Anti- Governmental East 128,331 2,730 - 131,061 IDPs by end of August 2014: Elements (AGEs), North 87,956 6,144 - 94,100 721,771 individuals. military operations, Central 83,413 4,458 - 87,871 Disaggregated data for harassment and Southeast 18,012 - - 18,012 August profiled: 49 % male intimidation by and 51% female; 48% adults AGE and cross - Central Highlands - - - - and 52% children. border shelling. Total 701,909 19,862 - 721,771 Main assistance PARTNERSHIPS needs profiled: Food and NFIs. Followed by shelter, cash grants and livelihoods. IDP Task Force agencies including UNHCR, WFP, UNICEF, NRC, DRC and IRC distributed The National IDP Task Force food, NFIs and cash grants to majority of the assessed families. UNHCR is coordinating is chaired by the Ministry of with other IDP task force agencies to ensure the urgent needs of the remaining families Refugees and Repatriation are met as soon as possible. (MoRR) and co-chaired by Lack of access due to ongoing conflicts and insecurity, especially in Helmand, Kunduz, Faryab, Logar, Nuristan and Kunar provinces, is a big challenge. -

Daily Situation Report 10 November 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

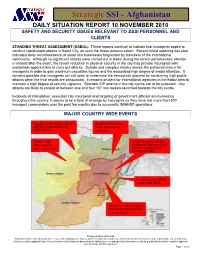

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 10 NOVEMBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past