IN SEARCH of ANSWERS: U.S. Military Investigations and Civilian Harm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Watching Brief Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of AREU and European Union. Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-34-1 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1905 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 Table of Contents About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit .................................................... II Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Past Experiences in Sedentarisation .......................................................................... 2 Sedentarisation Post-2001 ...................................................................................... 3 Drivers of Sedentarisation ......................................................................................... -

DEWS Weekly Report 17Th March 2014.Pdf (English)

March 17, 2014 DISEASE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM WER-10 (8th Yr) WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL REPORT Summary: The surveillance data collected for this week report is from 8 -14 March 2014. Out of 378 functional Sentinel sites (SS), 378 (100%) have submitted reports for Week-10 of 2014. Out of a total of 305,464 consultations (132,113 male, 173,351 female) recorded in Week-10 of 2014, 32.2 % or 98,380 (47,536 male, 50,844 female) consultations were reported due to DEWS target diseases. Main causes of consultations this week were Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) (28.9%) and Acute Diarrheal Diseases (ADD) (6.1%) from total clients in a continuing trend from the week before. 69 (44 male, 25 female) deaths resulted from Pneumonia, Diarrheal Diseases and Meningitis/Severely Ill Children, which includes 64 deaths (40 male, 24 female) caused by Pneumonia, no deaths caused by Diarrheal Diseases and 5 deaths (4 male, 1 female) caused by Meningitis/Severely Ill Children. In this reporting week, a Suspected Measles Outbreak reported from Paktya and Paktika provinces, a Rumor of Mumps Outbreak and a Suspected Measles Outbreak reported from Nangarhar province. Reports Received From Reporting Sites: As of March 14, 2014, 378 sentinel sites were functioning in eight epidemiological regions, in 34 provinces of Afghanistan. In this reporting week, 378 sentinel sites have sent their reports on new cases of DEWS target diseases recorded during the reporting week. Out of all events recorded in DEWS sentinel sites, 15 target diseases (priority diseases) are included in DEWS weekly epidemiological reports. Table-1: Status of Reports Received from DEWS Regions during Epidemiological Week-10, 2014 Region Central Central East Central West North North East West South East South East Total No. -

The a to Z Guide to Afghanistan Assistance

The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The A to Z Guide to Afghanistan Assistance 2nd Edition, August 2003 Writer: Shawna Wakefield Editor: Christina Bennett, Kathleen Campbell With special thanks to: Kristen Krayer, Nellika Little, Mir Ahmad Joyenda Cover illustration: Parniyan Design and Printing: The Army Press © 2003 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. Preface This is the second edition of The A to Z Guide to Afghanistan Assistance. Our first edition was brought out one year ago at a time of great change in Afghanistan. At that time, coordination mechanisms and aid processes were changing so fast that old hands and new arrivals alike were sometimes overwhelmed by the multiplicity of acronyms and references to structures and entities that had been recently created, abolished or re-named. Eighteen months after the fall of the Taliban and the signing of the Bonn Agreement, there are still rapid new developments, a growing complexity to the reconstruction effort and to planning processes and, of course, new acronyms! Our aim therefore remains to provide a guide to the terms, structures, mechanisms and coordinating bodies critical to the Afghanistan relief and reconstruction effort to help ensure a shared vocabulary and common understanding of the forces at play. We’ve also included maps and a contact directory to make navigating the assistance community easier. This 2nd edition also includes a section called “Resources,” containing information on such things as media organisations, security information, and Afghanistan-related web sites. Another new addition is a guide to the Afghan government. As the objective of so many assistance agencies is to support and strengthen government institutions, we felt that understanding how the Afghan government is structured is important to working in the current environment. -

State-Based Compensation for Victims of Armed Conflict

STATE-BASED COMPENSATION FOR VICTIMS OF ARMED CONFLICT: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN PRACTICE Alexandra Lian Fowler, B.Sc (Hons), LLB (Hons), MA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Studies School of Law University of Sydney 2018 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act (1968) (Cth). ________Alexandra Fowler________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of the professional staff of Sydney Law School and of Sydney University Library regarding research technique, as well as of the Australian Postgraduate Awards for vital financial support throughout the years researching and writing this thesis. Sincere gratitude goes to my supervisors at Sydney Law School - Professor Ben Saul, Associate Professor Emily Crawford, and in the initial stages, Professor Gillian Triggs. I am deeply grateful for their extremely helpful insight and advice, for the patience they have shown in evaluating and guiding repeated iterations of this work, and for keeping me focused and on track. It would simply not have been possible to complete this thesis without their expertise and support. My late father, Emeritus Professor (UNSW) Robert Thomas Fowler BSc PhD DSc (Eng), has been an immense source of inspiration. -

Afghan Portraits of Grief (2002)

AFGHAN PORTRAITS OF GRIEF The Civilian/Innocent Victims of U.S. Bombing in Afghanistan When the U.S. bombed the caves of Tora Bora in search of Osama bin Laden in December 2001, nearby villages were struck as well. Zeriba Taj, age 3, was hit in the head by fragments of a U.S. bomb. Zeriba’s father and three sisters were killed. FORWARD We all knew that the US would bomb Afghanistan after September 11th—we just didn’t know when. Most of us supported some sort of military action in response to the terrorist attacks. Many of us thought it would be good for Afghanistan for the Taliban to fall. I was sitting in an Afghan restaurant on October 7th, at the first gathering of the New York City area Afghan-American community since 9/11. In the room next to us we could hear CNN reporting breaking news that the bombing of Afghanistan had begun. At this gathering of 200 Afghan-Americans, while person after person denounced the attacks on the U.S., speakers reminded us that none of the hijackers were in fact Afghan. Elders in the community cried in front of us, reflecting on the misery that Afghanistan had endured for as long as I had been alive. They denounced the Taliban and Al Qaeda for holding the country hostage by refusing to cooperate with the United States. As the bombs fell, all I could think about was the family I had met just two months ago on my trip to Kandahar. It had been my first trip since I had left at the age of five. -

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

Mcallister Bradley J 201105 P

REVOLUTIONARY NETWORKS? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by Bradley J. McAllister (Under the Direction of Sherry Lowrance) ABSTRACT This dissertation is simultaneously an exercise in theory testing and theory generation. Firstly, it is an empirical test of the means-oriented netwar theory, which asserts that distributed networks represent superior organizational designs for violent activists than do classic hierarchies. Secondly, this piece uses the ends-oriented theory of revolutionary terror to generate an alternative means-oriented theory of terrorist organization, which emphasizes the need of terrorist groups to centralize their operations. By focusing on the ends of terrorism, this study is able to generate a series of metrics of organizational performance against which the competing theories of organizational design can be measured. The findings show that terrorist groups that decentralize their operations continually lose ground, not only to government counter-terror and counter-insurgent campaigns, but also to rival organizations that are better able to take advantage of their respective operational environments. However, evidence also suggests that groups facing decline due to decentralization can offset their inability to perform complex tasks by emphasizing the material benefits of radical activism. INDEX WORDS: Terrorism, Organized Crime, Counter-Terrorism, Counter-Insurgency, Networks, Netwar, Revolution, al-Qaeda in Iraq, Mahdi Army, Abu Sayyaf, Iraq, Philippines REVOLUTIONARY NETWORK0S? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by BRADLEY J MCALLISTER B.A., Southwestern University, 1999 M.A., The University of Leeds, United Kingdom, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY ATHENS, GA 2011 2011 Bradley J. -

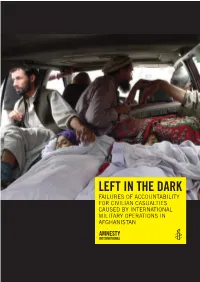

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

The Coils of the Anaconda: America's

THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN BY C2009 Lester W. Grau Submitted to the graduate degree program in Military History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date defended: April 27, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Lester W. Grau certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN Committee: ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date approved: April 27, 2009 ii PREFACE Generals have often been reproached with preparing for the last war instead of for the next–an easy gibe when their fellow-countrymen and their political leaders, too frequently, have prepared for no war at all. Preparation for war is an expensive, burdensome business, yet there is one important part of it that costs little–study. However changed and strange the new conditions of war may be, not only generals, but politicians and ordinary citizens, may find there is much to be learned from the past that can be applied to the future and, in their search for it, that some campaigns have more than others foreshadowed the coming pattern of modern war.1 — Field Marshall Viscount William Slim. -

Common Afghans‟, a Useful Construct for Achieving Results in Afghanistan

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 1 No. 6; June2011 „Common Afghans‟, A useful construct for achieving results in Afghanistan Fahim Youssofzai Associate Professor (Strategic Management) Department of Business Administration, RMC/CMR P.O. Box: 17000, Stn. Forces Kingston, Ontario, K7K 7B4, Canada E-mail: [email protected], Phone: (613) 541 6000 Abstract Considering the seemingly perpetual problems in Afghanistan, this paper defines a new construct – the Common Afghans – and argues why it should be considered in strategic reflections and actions related to stability of this country. It tries to show that part of ill-performance in comes from the fact that the contributions of an important stakeholder “the Common Afghans” are ignored in the processes undertaken by international stakeholders in this country since 2002. It argues why considering the notion “Common Afghans” is helpful for achieving concrete results related to different initiatives undertaken in Afghanistan, by different stakeholders. Key words: Afghanistan, Common Afghans, Accurate unit of analysis, Policies, Strategies 1. Introduction Afghanistan looks to be in perpetual turmoil. In a recent desperate reflection, Robert Blackwill, a former official in the Bush administration and former US ambassador to India suggests partition of Afghanistan since the US cannot win war in this county (POLITICO, 2010). On same mood, Jack Wheeler defines Afghanistan as “...a problem, not a real country…”. According to Wheeler, “…the solution to the problem is not a futile effort of “nation-building” – that effort is doomed to fail – it is nation-building‟s opposite: get rid of the problem by getting rid of the country…” (Wheeler, 2010). -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

“Troops in Contact”

“Troops in Contact” Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-362-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org September 2008 1-56432-362-5 “Troops in Contact” Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan Map of Afghanistan ............................................................................................................ 1 I. Summary......................................................................................................................2 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................7 Methodology .................................................................................................................