Taliban That They Cannot Win on the Battlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress in Afghanistan Bucharest Summit2-4 April 2008 Progress in Afghanistan

© MOD NL © MOD Canada © MOD Canada Progress in Afghanistan Progress in Bucharest Summit 2-4 April 2008 Bucharest Summit2-4 Progress in Afghanistan Contents page 1. Foreword by Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy, ..........................1 Jean-François Bureau, and NATO Spokesman, James Appathurai 2. Executive summary .........................................................................................................................................2 3. Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 • IED attacks and Counter-IED efforts 4 • Musa Qala 5 • Operations Medusa successes - Highlights Panjwayi and Zhari 6 • Afghan National Army 8 • Afghan National Police 10 • ISAF growth 10 4. Reconstruction and Development ............................................................................................... 12 • Snapshots of PRT activities 14 • Afghanistan’s aviation sector: taking off 16 • NATO-Japan Grant Assistance for Grassroots Projects 17 • ISAF Post-Operations Humanitarian Relief Fund 18 • Humanitarian Assistance - Winterisation 18 5. Governance ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 • Counter-Narcotics 20 © MOD Canada Foreword The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission is approaching five years of operations in Afghanistan. This report is a -

NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan

Nxxx,2009-09-05,A,009,Bs-BW,E3 THE NEW YORK TIMES INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2009 ØØN A9 NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan governor of Ali Abad, Hajji Habi- From Page A1 bullah, said the area was con- with the Afghan people.” trolled by Taliban commanders. Two 14-year-old boys and one The Kunduz area was once 10-year-old boy were admitted to calm, but much of it has recently the regional hospital here in Kun- slipped under the control of in- duz, along with a 16-year-old who surgents at a time when the Oba- later died. Mahboubullah Sayedi, ma administration has sent thou- a spokesman for the Kunduz pro- sands of more troops to other vincial governor, said most of the parts of the country to combat an estimated 90 dead were militants, insurgency that continues to gain judging by the number of charred strength in many areas. pieces of Kalashnikov rifles The region is patrolled mainly found. But he said civilians were by NATO’s 4,000-member Ger- also killed. man force, which is barred by In explaining the civilian German leaders from operating deaths, military officials specu- in combat zones farther south. lated that local people were con- The United States has 68,000 scripted by the Taliban to unload troops in Afghanistan, more than the fuel from the tankers, which any other nation; other countries were stuck near a river several fighting under the NATO com- miles from the nearest villages. mand have a combined total of about 40,000 troops here. -

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Watching Brief Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of AREU and European Union. Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-34-1 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1905 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 Table of Contents About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit .................................................... II Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Past Experiences in Sedentarisation .......................................................................... 2 Sedentarisation Post-2001 ...................................................................................... 3 Drivers of Sedentarisation ......................................................................................... -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Environment Scan: 01-15 Dec 2017 China

ENVIRONMENT SCAN: 01-15 DEC 2017 CHINA (Geo-Strat, Geo-Politics & Geo Economics) Brig Rajeev Kumar Bhutani (Retd) World Political Parties Dialogue Concludes with ‘Beijing Initiative’. One of the biggest meetings of global political parties wrapped-up in Beijing on 3 December 2017. It was the first major multilateral diplomacy event hosted by China after the recently concluded 19th CPC National Congress. It was also the first time the CPC held a high-level meeting with such a wide range of political parties from around the world. Over 600 delegates representing nearly 300 political parties and political organizations from over 120 countries attended the meeting.The meeting was officially reported to be a complete success with a broad consensus reached. Year end - China Focus: From Follower to Leader: China Emerges at High-Tech Frontier. After years of focusing on innovation, China has caught up fast. Silicon Valley has long been considered the most viable option for starting a business in the tech sector. Now, this is beginning to change. Known as "sea turtles," a growing number of overseas-educated Chinese are returning to their home country, turning down opportunities in Silicon Valley to make a splash in China's emerging tech sector. As the number of Chinese students at overseas universities surged to 544,500 in 2016, the number of sea turtles also surged, with 432,500 returning to China last year, nearly 60 percent more than 2012, according to the Ministry of Education. The reverse brain drain has benefited China's tech companies. A brilliant example is Royole, a company founded in 2012 by "sea turtle" Liu Zihong, a Stanford graduate. -

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy July 18, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45818 SUMMARY R45818 Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy July 18, 2019 Afghanistan has been a significant U.S. foreign policy concern since 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military Clayton Thomas campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported it. Analyst in Middle Eastern In the intervening 18 years, the United States has suffered approximately 2,400 military Affairs fatalities in Afghanistan, with the cost of military operations reaching nearly $750 billion. Congress has appropriated approximately $133 billion for reconstruction. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and most measures of human development have improved, although Afghanistan’s future prospects remain mixed in light of the country’s ongoing violent conflict and political contention. Topics covered in this report include: Security dynamics. U.S. and Afghan forces, along with international partners, combat a Taliban insurgency that is, by many measures, in a stronger military position now than at any point since 2001. Many observers assess that a full-scale U.S. withdrawal would lead to the collapse of the Afghan government and perhaps even the reestablishment of Taliban control over most of the country. Taliban insurgents operate alongside, and in periodic competition with, an array of other armed groups, including regional affiliates of Al Qaeda (a longtime Taliban ally) and the Islamic State (a Taliban foe and increasing focus of U.S. policy). U.S. -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-Geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence John O’Loughlin, Frank D. W. Witmer, and Andrew M. Linke1 Abstract: A team of political geographers analyzes over 5,000 violent events collected from media reports for the Afghanistan and Pakistan conflicts during 2008 and 2009. The violent events are geocoded to precise locations and the authors employ an exploratory spatial data analysis approach to examine the recent dynamics of the wars. By mapping the violence and examining its temporal dimensions, the authors explain its diffusion from traditional foci along the border between the two countries. While violence is still overwhelmingly concentrated in the Pashtun regions in both countries, recent policy shifts by the American and Pakistani gov- ernments in the conduct of the war are reflected in a sizeable increase in overall violence and its geographic spread to key cities. The authors identify and map the clusters (hotspots) of con- flict where the violence is significantly higher than expected and examine their shifts over the two-year period. Special attention is paid to the targeting strategy of drone missile strikes and the increase in their number and geographic extent by the Obama administration. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: H560, H770, O180. 15 figures, 1 table, 113 ref- erences. Key words: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Taliban, Al- Qaeda, insurgency, Islamic terrorism, U.S. military, International Security Assistance Forces, Durand Line, Tribal Areas, Northwest Frontier Province, ACLED, NATO. merica’s “longest war” is now (August 2010) nearing its ninth anniversary. It was Alaunched in October 2001 as a “war of necessity” (Barack Obama, August 17, 2009) to remove the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, and thus remove the support of this regime for Al-Qaeda, the terrorist organization that carried out the September 2001 attacks in the United States. -

Failed State Wars

Afghanistan: A War in Crisis! Anthony H. Cordesman September 10, 2019 Working draft, Please send comments and suggested additions to [email protected] Picture: SHAH MARAI/AFP/Getty Images Introduction The war in Afghanistan is at a critical stage. There is no clear end in sight that will result in a U.S. military victory or in the creation of a stable Afghan state. A peace settlement may be possible, but so far, this only seems possible on terms sufficiently favorable to the Taliban so that such peace may become an extension of war by other means and allow the Taliban to exploit such a settlement to the point where it comes to control large parts of the country. The ongoing U.S. peace effort is a highly uncertain option. There are no official descriptions of the terms of the peace that the Administration is now seeking to negotiate, but media reports indicate that it may be considering significant near-term U.S. force cuts, and a full withdrawal within one to two years of any settlement. Media reports indicate that the Administration is considering a roughly 50% cut in the total number of U.S. military personnel now deployed in Afghanistan — even if a peace is not negotiated. No plans have been advanced to guarantee a peace settlement, disarm part or all of the force on either side, provide any form of peace keeping forces, or provide levels of civil and security aid that would give all sides an incentive to cooperate and help stabilize the country. The Taliban has continued to reject formal peace negotiations with the Afghan government, and has steadily stepped up its military activity and acts of violence while it negotiates with the United States. -

1 USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive

USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive Summary The interviewee is a Farsi speaker and retired FSO who has had prior Afghan experience, including working with refugees during the period the Taliban was fighting to take over the country in 1995. He returned to Kabul in 2002 as chief of the political section, although retired, for seven months. He returned in 2003 and worked at the U.S. civil affairs mission in Herat for 6 months. He came back later in 2003 to Afghanistan working for the Asia Foundation. He worked on a PRT for approximately three months in late 2004 in Herat. The American presence was minimal when he got there. Security was excellent and the local warlord, Ismael Khan, was using revenues he siphoned from customs houses into development projects. Shortly after subject arrived in Herat, Khan was ousted in a brief battle by forces loyal to Kabul and with the threat of unrest U.S. forces were increased in the area. Our subject suggested to Khan that he make peace with the Kabul government, and he did, perhaps in part on the advice of subject. The Herat PRT had about one hundred American uniformed troops with three civilians, State, AID, Agriculture. Subject was the political advisor to the civil affairs staff, a reserve unit from Minnesota. But much of their work was soon taken over or undercut by the U.S. military task force commander brought in in response to the ouster of Khan. According to subject, the task force commander in the region saw himself as the political expert. -

Left in the Dark

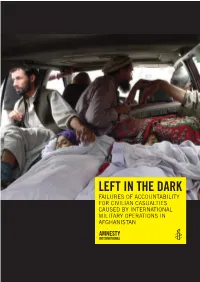

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Individuals and Organisations

Designated individuals and organisations Listed below are all individuals and organisations currently designated in New Zealand as terrorist entities under the provisions of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002. It includes those listed with the United Nations (UN), pursuant to relevant Security Council Resolutions, at the time of the enactment of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002 and which were automatically designated as terrorist entities within New Zealand by virtue of the Acts transitional provisions, and those subsequently added by virtue of Section 22 of the Act. The list currently comprises 7 parts: 1. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with the Taliban By family name: • A • B,C,D,E • F, G, H, I, J • K, L • M • N, O, P, Q • R, S • T, U, V • W, X, Y, Z 2. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with the Taliban 3. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida By family name: • A • B • C, D, E • F, G, H • I, J, K, L • M, N, O, P • Q, R, S, T • U, V, W, X, Y, Z 4. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida 5. A list of entities where the designations have been deleted or consolidated • Individuals • Entities 6. A list of entities where the designation is pursuant to UNSCR 1373 1 7. A list of entities where the designation was pursuant to UNSCR 1373 but has since expired or been revoked Several identifiers are used throughout to categorise the information provided.