Columbia ’68: What Happened?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soldiers and Veterans Against the War

Vietnam Generation Volume 2 Number 1 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Article 1 Against the War 1-1990 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1990) "GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol2/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GI RESISTANCE: S o l d ie r s a n d V e t e r a n s AGAINST THE WAR Victim am Generation Vietnam Generation was founded in 1988 to promote and encourage interdisciplinary study of the Vietnam War era and the Vietnam War generation. The journal is published by Vietnam Generation, Inc., a nonprofit corporation devoted to promoting scholarship on recent history and contemporary issues. ViETNAM G en eratio n , In c . ViCE-pRESidENT PRESidENT SECRETARY, TREASURER Herman Beavers Kali Tal Cindy Fuchs Vietnam G eneration Te c HnIc a I A s s is t a n c e EdiTOR: Kali Tal Lawrence E. Hunter AdvisoRy BoARd NANCY ANISFIELD MICHAEL KLEIN RUTH ROSEN Champlain College University of Ulster UC Davis KEVIN BOWEN GABRIEL KOLKO WILLIAM J. SEARLE William Joiner Center York University Eastern Illinois University University of Massachusetts JACQUELINE LAWSON JAMES C. -

Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968

THE POLITICS OF SPACE: STUDENT COMMUNES, POLITICAL COUNTERCULTURE, AND THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PROTEST OF 1968 Blake Slonecker A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Peter Filene Reader: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Reader: Jerma Jackson © 2006 Blake Slonecker ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT BLAKE SLONECKER: The Politics of Space: Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968 (Under the direction of Peter Filene) This thesis examines the Columbia University protest of April 1968 through the lens of space. It concludes that the student communes established in occupied campus buildings were free spaces that facilitated the protestors’ reconciliation of political and social difference, and introduced Columbia students to the practical possibilities of democratic participation and student autonomy. This thesis begins by analyzing the roots of the disparate organizations and issues involved in the protest, including SDS, SAS, and the Columbia School of Architecture. Next it argues that the practice of participatory democracy and maintenance of student autonomy within the political counterculture of the communes awakened new political sensibilities among Columbia students. Finally, this thesis illustrates the simultaneous growth and factionalization of the protest community following the police raid on the communes and argues that these developments support the overall claim that the free space of the communes was of fundamental importance to the protest. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Peter Filene planted the seed of an idea that eventually turned into this thesis during the sort of meeting that has come to define his role as my advisor—I came to him with vast and vague ideas that he helped sharpen into a manageable project. -

The Personal Account of an American Revolutionary and Member Ofthe Weather Underground

The Personal Account of an American Revolutionary and Member ofthe Weather Underground Mattie Greenwood U.S. in the 20th Century World February, 10"'2006 Mr. Brandt OH GRE 2006 1^u St-Andrew's EPISCOPAL SCHOOL American Century Oral History Project Interviewee Release Form I, I-0\ V 3'CoVXJV 'C\V-\f^Vi\ {\ , hereby give and grant to St. Andrew's (inter\'iewee) Episcopal School the absolute and unqualified right to the use ofmy oral histoiy memoir conducted by VA'^^X'^ -Cx^^V^^ Aon 1/1 lOip . I understand that (student interviewer) (date) the purpose ofthis project is to collect audio- and video-taped oral histories of fust-hand memories ofa particular period or event in history as part ofa classroom project (The American Century Projeci), I understand that these interviews (tapes and transcripts) will be deposited in the Saint Andrew's Episcopal School library and archives for the use by future students, educators and researchers. Responsibility for the creation of derivative works will be at the discretion ofthe librarian, archivist and/or project coordinator. 1 also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, books, audio or video documentaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles, public performance, or presentation on the World Wide Web at the project's web site www.americancenturyproject.org or successor technologies. In making this contract I understand that J am sharing with St. Andrew's Episcopal School librai"y and archives all legal title and literar)' property rights which J have or may be deemed to have in my interview as well as my right, title and interest in any copyright related to this oral history interview which may be secured under the laws now or later in force and effect in the United Slates of America. -

68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A

Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Professer C. Greig Crysler Professor Richard Walker Summer 2015 Sagan Copyright page Sagan Abstract Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Political protest is an increasingly frequent occurrence in urban public space. During times of protest, the use of urban space transforms according to special regulatory circumstances and dictates. The reorganization of economic relationships under neoliberalism carries with it changes in the regulation of urban space. Environmental design is part of the toolkit of protest control. Existing literature on the interrelation of protest, policing, and urban space can be broken down into four general categories: radical politics, criminological, technocratic, and technical- professional. Each of these bodies of literature problematizes core ideas of crowds, space, and protest differently. This leads to entirely different philosophical and methodological approaches to protests from different parties and agencies. This paper approaches protest, policing, and urban space using a critical-theoretical methodology coupled with person-environment relations methods. This paper examines political protest at American Presidential National Conventions. Using genealogical-historical analysis and discourse analysis, this paper examines two historical protest event-sites to develop baselines for comparison: Chicago 1968 and Dallas 1984. Two contemporary protest event-sites are examined using direct observation and discourse analysis: Denver 2008 and St. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Thomas Byrne Edsall Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4d5nd2zb No online items Inventory of the Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Thomas Byrne 88024 1 Edsall papers Title: Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Date (inclusive): 1965-2014 Collection Number: 88024 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 259 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes.(113.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, memoranda, poll data, statistics, printed matter, and photographs relating to American politics during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, especially with regard to campaign contributions and effects on income distribution; and to the gubernatorial administration of Michael Dukakis in Massachusetts, especially with regard to state economic policy, and the campaign of Michael Dukakis as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1988; and to social conditions in the United States. Creator: Edsall, Thomas Byrne Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover -

An End to History

AN END TO HISTORY Mario Savio Mario Savio, a leader of the Free Speech Movement, seemed to articulate the pentup feelings and frustrations of many students. In one of the most famous speeches of the early new left, Savio told a huge campus rally to resist the Berkeley administration: "There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part, you can't even tacitly take part. And you've Got to put your bodies upon the Gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and you've Got to make it stop. And you've Got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from workinG at all." In the essay that follows, written in 1964, Savio enunciates many new left themes: the hierarchical and bureaucratic nature of American society and of the University of California, the alienation of students, the limitation of speech to that which is not critical political speech, the existence of racial injustice, and the links between the civil rights movement and the student movement Last summer I went to Mississippi to join the struGGle there for civil riGhts. This fall I am enGaGed in another phase of the same struGGle, this time in Berkeley. The two battlefields may seem quite different to some observers, but this is not the case. The same riGhts are at stake in both places‐the riGht to participate as citizens in democratic society and the riGht to due process of law. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS June 4, 1976 Mr

16728 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 4, 1976 Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Yes. speeded up the work of the Senate, and on Monday, and by early I mean as early Mr. ALLEN. The Senator spoke of pos I am glad the distinguished assistant ma as very shortly after 11 a.m., and that a sible quorum calls and votes on Monday. jority leader is now following that policy. long working day is in prospect for I would like to comment that I feel the [Laughter.] Monday. present system under which we seem to Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Well, my dis be operating, of having all quorum calls tinguished friend is overly charitable to RECESS TO MONDAY, JUNE 7, 1976, go live, has speeded up the work of the day in his compliments, but I had sought AT 11 A.M. Senate. There has only been one quorum earlier today to call off that quorum call call today put in by the distinguished as but the distinguished Senator from Ala Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, sistant majority leader, and I think the bama, noting that in his judgment I un if there be no further business to come Members of the Senate, realizing that doubtedly was seeking to call off the before the Senate, I move, in accordance a quorum call is going to go live, causes quorum call for a very worthy purpose, with the order previously entered, that them to come over to the Senate Cham went ahead to object to the calling off of the Senate stand in recess until the hour ber when a quorum call is called. -

First ISL Cage Title 1N 16 Years

First ISL cage title 1n• 16 years_~:_~;· Photos by David Cahnmann U-HIGH'S GOT a new jug band, van der Meulen, washtub base; Senior Peter Getzels and Simeon Alev, both formed for Arts Week. Jamming in a Doug Patinkin, violin; and Senior harmonica. "We'll play all the old practice session from left are: Junior David Weber, piano. Missing from the favorites," said Director Doug, "and a Richard Johnson, kazoo; Senior Peter photo are Seniors Fred Elfman, banjo; new new cuts." Vol. 48, No. 8 • UniversityHighSchool,1362East59thSt.,Chicago,Ill.60637 • Tuesday, Feb. 27, 1973 From a band to a bunny: Arts Week starts Monday By Carol Siegel, Bernarda Alba," Sat., March 10. Awards for art will be given in Arts editor Senior Julie Needlman is the following categories: Drawing, directing "The House .... "The crafts, prints, sculpture and A jug band they've formed (see three-act tragedy, by Frederica constructions, mixed media, photo), films theylve produced Garcia Lorca, deals with the lives photography, and painting. (one using animated clay), and of five sisters who compete for the plays they've written (including love of one man. Entries will be judged by Ar one about a bunny man) will be THE CAST includes Freshman chitect John van der Meulen, among the unusual programs U father of Senior Peter; com Highers present during the sixth Suzanne Harrison and Carolyn O'Connor; Juniors Ann Morrison, mercial artist and photographer annual Arts Week, which begins Merwin Sanders; Middle School Monday. Lea Shafer, Mariye Inouye and Laura Cowell; and Seniors Art Teacher Martha Ray; Physics Three plays and a dance will be Gretchen Bogue, Ellen Coulter and Teacher and, outside school, presented by Student Ex Carol Lashof. -

Uncivil Wars: Liberal Crisis and Conservative Rebirth 1961–1972

CHAPTER 28 Uncivil Wars: Liberal Crisis and Conservative Rebirth 1961–1972 . CHAPTER OUTLINE 1. The 1964 Election a. Lyndon Johnson was the opposite of The following annotated chapter outline will help Kennedy. A seasoned Texas politician you review the major topics covered in this chapter. and longtime Senate leader, he had I. Liberalism at High Tide risen to wealth and political eminence A. John F. Kennedy’s Promise without too many scruples. But he 1. President Kennedy called upon the never forgot his modest, hill-country American people to serve and improve origins or lost his sympathy for the their country. His youthful enthusiasm downtrodden. inspired a younger generation and laid the b. Johnson lacked the Kennedy style, but groundwork for an era of liberal reform. he capitalized on Kennedy’s 2. Kennedy was not able to fulfill his assassination, applying his astonishing promise or his legislative suggestions such energy and negotiating skills to bring as health insurance for the aged, a new to fruition several of Kennedy’s stalled antipoverty program, or a civil rights bill programs and many more of his own, because of opposition in the Senate. in the ambitious Great Society. 3. On November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, c. On assuming the presidency, Johnson President Kennedy was assassinated by promptly and successfully pushed for Lee Harvey Oswald; Lyndon Johnson was civil rights legislation as a memorial to sworn in as president. his slain predecessor (see Chapter 27). 4. Kennedy’s youthful image, the trauma of His motives were complex. As a his assassination, and the sense that southerner who had previously Americans had been robbed of a opposed civil rights for African promising leader contributed to a powerful Americans, Johnson wished to prove mystique that continues today. -

Frank Lazarus from Providence

Templ e' Be t h- EL Broad &1Glenham Sts. 1 HERALD t:comm;;~~~~~~entators have advan-~ced! THE JEWisH , the theory t hat Naziis m's defeat VOL. XVI No. 38 PROVIDENCE. R. L. FRIDAY. NOVEMBER 14, 1941 5 CENTS THI COPY could be hastened by launch ing ------- - --------------- ------ --------------- - -------- --- an idea greater than Hitler's Emanuel Speaker . F th f A , t. epic idea of world domination. w ·s ·,. Louis Adamic and t he Christ- our· ave o n I- eml ISm ian Science Monitor believe that ,Goebbel/srouse fear inar ticle,the German try~ng people, to a- Reported Sweep,·n· g . Germ-any is the tip-off that a sincere cam- paign of ideas is necessary n ow , S k "J f " to w in over the. dominated popu- 600 Delegates UJA Speaker ee ew- ree 0 la~:~. ~~b:::: t:\he wall" pep To Attend Meeting Reich by April 1 talk that Nazi propagandists are ( 'd D · ' employing does not mean that To Elect Officers ons1 er eportation Hitler is at the end of his rope. · Of 120,000 to Poland But it does suggest how tremend- For 1941 Campaign BERLIN. --. A fourth wave of ously important it is for the Al J udge Morris Rolbenberg, na anti-Semitism in eight years of - -"\ lies to develop more concrete tional co-chairman of the United Nazi rule, repor tedly. aimed at plans for a better world after the Palestine Appeal, will address creating a 11Jew-free Reich" by w a r is over. It is up to t he Al ,more than 600 delegates, repre April 1, threatened Germany's lied strategists·to prove that Hit senting 60 city organizations, at remaining 120,000 Jews with ler's defeat will be better for a meeting of the Providence Uni wholesale deportation lo Poland., German's than Hitler's victory. -

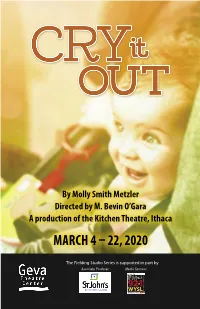

March 4 – 22, 2020

By Molly Smith Metzler Directed by M. Bevin O’Gara A production of the Kitchen Theatre, Ithaca MARCH 4 – 22, 2020 The Fielding Studio Series is supported in part by Associate Producer: Media Sponsor: 1 2 ABOUT GEVA THEATRE CENTER Geva Theatre Center is your not-for-profit theatre company dedicated to creating and producing professional theatre productions, programs and services of a national standard. As Rochester’s flagship professional theatre, Geva is the most attended regional theatre in New York State, and one of the 25 most subscribed in the country, serving up to 160,000 patrons annually, including 20,000 students. Founded in 1972 by William Selden and Cynthia Mason Selden, Geva was originally housed in the Rochester Business Institute building on South Clinton Avenue. In 1982, Geva purchased and converted its current space – formerly a NYS Arsenal designed by noted Rochester architect Andrew J Warner and built in 1868 – and opened its new home at the Richard Pine Theatre in March 1985. Geva operates two venues – the 516-seat Elaine P. Wilson Stage and the 180-seat Ron & Donna Fielding Stage. As one of the country’s leading theatre companies and a member of the national League of Resident Theatres, Geva produces a varied contemporary repertoire from musicals to world premieres celebrating the rich tapestry of our diverse community. We draw upon the talents of some of the country’s top actors, directors, designers and writers who are shaping the American Theatre scene. Geva’s education programs serve 20,000 students annually through student matinees, in-school workshops, theatre tours, career day, the acclaimed Summer Academy training program, and opportunities such as the Stage Door Project, which pairs a local school with a production in the Geva season giving students an exclusive look into the entire process of producing a show.