The Island of the Sun: Spatial Aspect of Solstices in Early Greek Thought Tomislav Bilić

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues Paris Tsartas University of the Aegean, Michalon 8, 82100 Chios, Greece The paperanalyses two issuesthat have characterised tourism development inGreek insularand coastalareas in theperiod 1970–2000. The firstissue concerns the socioeco- nomic and culturalchanges that have taken place in theseareas and ledto rapid– and usuallyunplanned –tourismdevelopment. The secondissue consists of thepolicies for tourismand tourismdevelopment atlocal,regional and nationallevel. The analysis focuseson therole of thefamily, social mobility issues,the social role of specific groups, and consequencesfor the manners, customs and traditionsof thelocal popula- tion.It also examines the views and reactionsof localcommunities regarding tourism and tourists.There is consideration of thenew productive structuresin theseareas, including thedowngrading of agriculture,the dependence of many economicsectors on tourism,and thelarge increase in multi-activityand theblack economy. Another focusis on thecharacteristics of masstourism, and on therelated problems and criti- cismsof currenttourism policies. These issues contributed to amodel of tourism development thatintegrates the productive, environmental and culturalcharacteristics of eachregion. Finally, the procedures and problemsencountered in sustainabledevel- opment programmes aiming at protecting the environment are considered. Social and Cultural Changes Brought About by Tourism Development in the Period 1970–2000 The analysishere focuseson three mainareas where these changesare observed:sociocultural life, productionand communication. It should be noted thata large proportionof all empirical studies of changesbrought aboutby tourism development in Greece have been of coastal and insular areas. Social and cultural changes in the social structure The mostsignificant of these changesconcern the family andits role in the new ‘urbanised’social structure, social mobility and the choicesof important groups, such as young people and women. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

CEPR European Conference on Household Finance 2018 WELCOME GUIDE Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] The Conference Venue Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Grand Hotel Ortigia https://www.grandhotelortigia.it/ Des Etrangers http://www.desetrangers.com/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Palazzo Gilistro https://www.palazzogilistro.it/ Hotel Gutkowski http://www.guthotel.it/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Transport Catania Airport Fontanarossa http://www.aeroporto.catania.it/ Train Station Siracusa https://goo.gl/6AK4Ee Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] 1 – The Greek theatre Impressive, solemn, intriguing, with stunning views. It may happen that, while sitting on the big stone steps , you hear the voices of the great Greek heroes, Agamemnon, Medea or Oedipus, even if there are no actors on the stage …this is such an evocative place! It keeps evidences of several historic periods, from the prehistoric ages to Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era. The Greek Theatre is one of the biggest in the world, entirely carved into the rock. In ancient times it was used for plays and popular assemblies, today it is the place where the Greek tragedies live again through the Series of Classical Performances that take place every year thanks to the INDA, National Institute of Ancient Drama. -

Alexander Jones Calendrica I: New Callippic Dates

ALEXANDER JONES CALENDRICA I: NEW CALLIPPIC DATES aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 129 (2000) 141–158 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 141 CALENDRICA I: NEW CALLIPPIC DATES 1. Introduction. Callippic dates are familiar to students of Greek chronology, even though up to the present they have been known to occur only in a single source, Ptolemy’s Almagest (c. A.D. 150).1 Ptolemy’s Callippic dates appear in the context of discussions of astronomical observations ranging from the early third century B.C. to the third quarter of the second century B.C. In the present article I will present new attestations of Callippic dates which extend the period of the known use of this system by almost two centuries, into the middle of the first century A.D. I also take the opportunity to attempt a fresh examination of what we can deduce about the Callippic calendar and its history, a topic that has lately been the subject of quite divergent treatments. The distinguishing mark of a Callippic date is the specification of the year by a numbered “period according to Callippus” and a year number within that period. Each Callippic period comprised 76 years, and year 1 of Callippic Period 1 began about midsummer of 330 B.C. It is an obvious, and very reasonable, supposition that this convention for counting years was instituted by Callippus, the fourth- century astronomer whose revisions of Eudoxus’ planetary theory are mentioned by Aristotle in Metaphysics Λ 1073b32–38, and who also is prominent among the authorities cited in astronomical weather calendars (parapegmata).2 The point of the cycles is that 76 years contain exactly four so-called Metonic cycles of 19 years. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

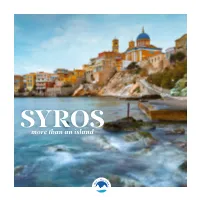

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

In Focus: Corfu, Greece

OCTOBER 2019 IN FOCUS: CORFU, GREECE Manos Tavladorakis Analyst Pavlos Papadimitriou, MRICS Director www.hvs.com HVS ATHENS | 17 Posidonos Ave. 5th Floor, 17455 Alimos, Athens, GREECE Introduction The region of the Ionian Islands consists of the islands in the Ionian Sea on the western coast of Greece. Since they have long been subject to influences from Western Europe, the Ionian Islands form a separate historic and cultural unit than that of continental Greece. The region is divided administratively into four prefectures (Corfu, Lefkada, Kefallinia and Zakinthos) and comprises the islands of Kerkira (Corfu), Zakinthos, Cephalonia (Kefallinia), Lefkada, Ithaca (Ithaki), Paxi, and a number of smaller islands. The Ionian Islands are the sunniest part of Greece, but the southerly winds bring abundant rainfall. The region is noted for its natural beauty, its long history, and cultural tradition. It is also well placed geographically, since it is close to both mainland Greece and Western Europe and thus forms a convenient stepping-stone, particularly for passenger traffic between Greece and the West. These factors have favored the continuous development of tourism, which has become the most dynamic branch of the region’s economy. Island of Corfu CORFU MAP Corfu is located in the northwest part of Greece, with a size of 593 km2 and a costline, which spans for 217 km, is the largest of the Ionian Islands. The principal city of the island and seat of the municipality is also named Corfu, after the island’s name, with a population of 32,000 (2011 census) inhabitants. Currently, according to real estate agents, foreign nationals who permanently reside on Corfu are estimated at 18,000 individuals. -

Floating Adventure GR Islands of Corfu

Greece Active Journeys Escorted tour Cycling Tour descriptions and distances Day 1 Corfu Day 2 28 km Sivota - Parga - Lefkas Day 3 30 km Lefkas Day 4 45 km Islands of Corfu by Bike Cephalonia Day 5 20 km + On the Ionian Islands off the west coast of Greece, this is surely the most stunning- Ithaca & Meganisi 15 km ly beautiful side: the main attraction is the crystal clear blue shimmering Ionian Sea. Day 6 50 km Come and discover why centuries of Venetian influence dominate the archipelago Mitikas - Lefkas of the Ionian Islands. Day 7 24 km Paxos & Corfu From Corfu, which was the dream island of the unforgettable Austrian empress Day 8 Sissi, this journey will lead us to areas that are not very well known here. The Corfu Greeks themselves have been travelling to these islands for holidays for a welcome respite from the city. Discover the famous island of Ithaca, said to have been the home of Odysseus, you will never forget the green bird sanctuary island of Lefkas, the fantastic mountain Tour Details 2018 world of Kefallonia and the beautiful olive woods of the small island of Paxos. We Dates: April 14, 21, 28 enjoy our stay on board the wooden motor yacht and let us be pampered by the Oct 6, 13, 20, 27 excellent Greek cuisine and the coziness of the ship. Come enjoy this Floating Adventure with Active Journeys! Cost: $2495 per person Single Supplement: On request Fact Sheet Length: 8 days / 7 nights Includes : E-Bike Info : Bike rental: $175 • 7 nights accommodation, with 2 • E-bike rental: $350 Grade: Intermediate days all meals and 5 days break- fast & lunch or dinner on boat in- • Limited supplies on boat, so Starts/Ends Corfu reservations recommended cluded Above deck cabin: $185 p.p. -

Greek Cultures, Traditions and People

GREEK CULTURES, TRADITIONS AND PEOPLE Paschalis Nikolaou – Fulbright Fellow Greece ◦ What is ‘culture’? “Culture is the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts […] The word "culture" derives from a French term, which in turn derives from the Latin "colere," which means to tend to the earth and Some grow, or cultivation and nurture. […] The term "Western culture" has come to define the culture of European countries as well as those that definitions have been heavily influenced by European immigration, such as the United States […] Western culture has its roots in the Classical Period of …when, to define, is to the Greco-Roman era and the rise of Christianity in the 14th century.” realise connections and significant overlap ◦ What do we mean by ‘tradition’? ◦ 1a: an inherited, established, or customary pattern of thought, action, or behavior (such as a religious practice or a social custom) ◦ b: a belief or story or a body of beliefs or stories relating to the past that are commonly accepted as historical though not verifiable … ◦ 2: the handing down of information, beliefs, and customs by word of mouth or by example from one generation to another without written instruction ◦ 3: cultural continuity in social attitudes, customs, and institutions ◦ 4: characteristic manner, method, or style in the best liberal tradition GREECE: ANCIENT AND MODERN What we consider ancient Greece was one of the main classical The Modern Greek State was founded in 1830, following the civilizations, making important contributions to philosophy, mathematics, revolutionary war against the Ottoman Turks, which started in astronomy, and medicine. -

La Ulyxea ... Trad. De Griego En Lengua Castellana Por ... Gonzalo Perez

— ” LA UL IX E A DE HO ME RO, TR A D UCI DA DE G RIE G o en lengua Castellana P0R EL SECRETARIO GONZALa P E RE 2. TO MO SE GU N D o, CON L I CE NCI A: En Madrid en la Imprenta de Francisco Xavier Garcia, año 1767. :) |-→==============) ! <!” *|-|- · |-… *· į|-- -|- |- ---- |- ·|- |- ·|- ----- ·|- |- + ----|- |- ~ ! · ·|- -|- ·|- ---- |- |- |-|- |-|- |-|-|-|- |- · |-|-|- - -|- |-----|- A R G U M E N T o DEL ONCE N o L I B RO D E L A U L Y X E A DE HO MIERO. rº Uenta como Ulyres, siguiendo lo que le man dó Circe, bajó al infierno, y oyó á Tiresias el adevino lo que le havia de suceder á él y á sus compañeros: y los cavalleros y señoras que vió en el infierno y á su madre, y á algunos de los que mu rieron sobre Troya ; y las penas que se daban en el infierno, s T). l 372 d 0 LIB RO ONCE NO - DE LA U L Y x E A DE HO ME R O. - D? que ya llegamos á do havia Quedado la galera en la marina, 4). Varamosla en la mar, y con presteza is El mastel levantamos, y estendimos Las velas, y metimos las ovejas l Que haviamos traído dentro della. Tambien nos embarcamos luego todos l. Con una gran tristeza, derramando l Lagrimas de los ojos sin medida. Luego la Diosa Circe bien hablada - Nos embió un buen viento, que le daba Por popa á la galera, tan suave, Que hinchaba las velas blandamente. Dejando pues las armas y los remos, Cada uno en su lugar muy bien sentados, Dejamonos llevar al viento fresco, Y al que el timon regia: de manera Que todo un dia entero duró el viento; Y sin calmar un punto navegamos En popa, y con las velas muy tendidas. -

The Draconic Gearing of the Antikythera Mechanism: Assembling the Fragment D, Its Role and Operation

The Draconic gearing of the Antikythera Mechanism: Assembling the Fragment D, its role and operation A.Voulgaris1, C.Mouratidis2, A.Vossinakis3, G.Bokovos4 (Submitted 14 January 2020) 1Municipality of Thessaloniki, Directorate Culture and Tourism, Thessaloniki, GR-54625, Greece 2Hellenic Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs, Kos, GR-85300, Greece 3Thessaloniki Astronomy Club, Thessaloniki, GR-54646, Greece 4Thessaloniki Science Center and Technology Museum-Planetarium, Thermi, GR-57001, Greece Abstract The unplaced Fragment D of the Antikythera Mechanism with an unknown operation was a mystery since the beginning of its discovery. The gear-r1, which was detected on the Fragment radiographies by C. Karakalos, is preserved in excellent condition, but this was not enough to correlate it to the existing gear trainings of the Mechanism. The suggestion that this gear could be a part of the hypothetical planet indication gearing is still a hypothesis since no mechanical evidence has been preserved. After the analysis of AMRP tomographies of Fragment D and its mechanical characteristics revealed that it could be part of the Draconic gearing. Although the Draconic cycle was well known during the Mechanism’s era as represents the fourth Lunar cycle, it seems that it is missing from the Antikythera Mechanism. The study of Fragment D was supported by the bronze reconstruction of the Draconic gearing by the authors. The adaptation of the Draconic gearing on the Antikythera Mechanism improves its functionality and gives answers on several questions. 1. Introduction. The Antikythera Mechanism, a geared machine based on the lunar cycles The Antikythera Mechanism a creation of an ingenious manufacturer of the Hellenistic era was a geared machine capable of performing complex astronomical calculations, mostly based on the lunar periodic cycles. -

University Microfilms International

ANCIENT EUBOEA: STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF A GREEK ISLAND FROM EARLIEST TIMES TO 404 B.C. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vedder, Richard Glen, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 05:15:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290465 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame.