Cultic Connections in Pindar's Nemean 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

CEPR European Conference on Household Finance 2018 WELCOME GUIDE Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] The Conference Venue Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Grand Hotel Ortigia https://www.grandhotelortigia.it/ Des Etrangers http://www.desetrangers.com/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Palazzo Gilistro https://www.palazzogilistro.it/ Hotel Gutkowski http://www.guthotel.it/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Transport Catania Airport Fontanarossa http://www.aeroporto.catania.it/ Train Station Siracusa https://goo.gl/6AK4Ee Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] 1 – The Greek theatre Impressive, solemn, intriguing, with stunning views. It may happen that, while sitting on the big stone steps , you hear the voices of the great Greek heroes, Agamemnon, Medea or Oedipus, even if there are no actors on the stage …this is such an evocative place! It keeps evidences of several historic periods, from the prehistoric ages to Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era. The Greek Theatre is one of the biggest in the world, entirely carved into the rock. In ancient times it was used for plays and popular assemblies, today it is the place where the Greek tragedies live again through the Series of Classical Performances that take place every year thanks to the INDA, National Institute of Ancient Drama. -

Classic Collection Extrait De Parfum

classic collection Extrait de Parfum Here they are, inspired by travel notes in a TTPROF/ARE TTPROF/LAU Extrait de Parfum ROUND Extrait de Parfum SQUARE as ancient and well-worn as the knowledge of leather-bound notebook 100 ml - 3,4 fl. oz. 100 ml - 3,4 fl. oz. our craft (passed down for three generations): two new creations, perfumes with notes 66 mm h 97 mm 56x56 mm h 97 mm of memory and soul, perfectly capturing the emotions. These perfumes represent two 2,60 in h 3,82 in 2,20x2,20 in h 3,82 in more steps in this marvellous and ongoing journey, towards the magnificence of fire and emotions of fantastical experiences and encounters. The most carefree and joyful stop on this incredible journey is the beautiful Sicily, where History, Art and Nature are intertwined The most bohemian stop on this unforgettable journey is the mythical Paris during a rainy autumn day, but warm with winding in an enchanting sea of emotions. Wild beaches, ancient ruins and squares surrounded by baroque buildings frame this Mediterranean watercolours, blended as in painting by Renoir. The smell of the rain beating on the slate roof mixes with the stone streets lit by place that embodies one of the most mysterious and, at the same time, oldest of Italian beauties. All the colourful sounds of Sicily dim lights. A small fire at a crossroads of Montmartre heats musicians and acrobats that await tourists after the rain. The magical are enclosed in this exquisite perfume extract. You will find delicious fruits paired with sublime smelling flowers, before reverberating atmosphere is seeped with precious and rare scents that echo the mysterious art of a timeless place. -

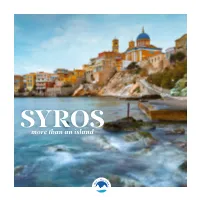

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

8 Tales of Lovers.Pdf

NAME ________________________________________________ PAGE 1 Complete this handout as you read “Eight Brief Tales of Lovers” on p.135-159. Pyramus and Thisbe (pronounced PEER-uh-mus and THIZ-bee) What separates Pyramus and Thisbe? How do they plan to be together? How does their plan fail? What natural phenomenon is explained through this story? Does this tale remind you of another famous love story? Hmmm... Orpheus and Eurydice (pronounced OR-fee-us and your-ID-ih-see) What special talent/gift does Orpheus possess? Why? How do these two lovers meet? What happens to Eurydice? What must Orpheus do / where must he go? Is Orpheus successful? Explain. What happens to Orpheus? What natural phenomenon is explained through this story? Can you name a biblical story that has a similar plot? Ceyx and Alcyone (pronounced SEE-iks and al-SIGH-un-ee) What kind of journey must Ceyx undertake? Why is Alcyone concerned? Why is Ceyx happy as he dies? How does Juno (Hera) answer Alcyone’s prayers? Who assists Hera? What natural phenomenon is explained through this story? Pygmalion and Galatea (pronounced pig-MALE-yun and gal-uh-TEE-uh) What is Pygmalion’s occupation? How does he feel about women? Which goddess pities Pygmalion? What does she do? How does this story relate to the musical My Fair Lady? Baucis and Philemon (pronounced BAW-sis and fill-EE-mun) PAGE 2 Describe this couple. Which gods play a role in this tale? How? What becomes of the people in the countryside? What is the couple’s only wish? What lesson can be learned from this tale? What objects -

Dissertation Master

APOSTROPHE TO THE GODS IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES, LUCAN’S PHARSALIA, AND STATIUS’ THEBAID By BRIAN SEBASTIAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Brian Sebastian 2 To my students, for believing in me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great many people over a great many years made this possible, more than I could possibly list here. I must first thank my wonderful, ideal dissertation committee chair, Dr. Victoria Pagán, for her sage advice, careful reading, and steadfast encouragement throughout this project. When I grow up, I hope I can become half the scholar she is. For their guidance and input, I also thank the members of my dissertation committee, Drs. Jennifer Rea, Robert Wagman, and Mary Watt. I am very lucky indeed to teach at the Seven Hills School, where the administration has given me generous financial support and where my colleagues and students have cheered me on at every point in this degree program. For putting up with all the hours, days, and weeks that I needed to be away from home in order to indulge this folly, I am endebted to my wife, Kari Olson. I am grateful for the best new friend that I made on this journey, Generosa Sangco-Jackson, who encouraged my enthusiasm for being a Gator and made feel like I was one of the cool kids whenever I was in Gainesville. I thank my parents, Ray and Cindy Sebastian, for without the work ethic they modeled for me, none of the success I have had in my academic life would have been possible. -

The Will of Zeus in the Iliad 273

Kerostasia, the Dictates of Fate, and the Will of Zeus in the Iliad 273 KEROSTASIA, THE DICTATES OF FATE, AND THE WILL OF ZEUS IN THE ILIAD J. V. MORRISON Death speaks: There was a merchant in Baghdad who sent his servant to market to buy provisions and in a little while the servant came back, white and trembling, and said, “Master, just now when I was in the market-place I was jostled by a woman in the crowd and when I turned I saw it was Death that jostled me. She looked at me and made a threatening gesture; now, lend me your horse, and I will ride away from this city and avoid my fate. I will go to Samarra and there Death will not find me.” The merchant lent him his horse, and the servant mounted it, and he dug his spurs in its flanks and as fast as the horse could gallop he went. Then the merchant went down to the market- place and he saw me standing in the crowd and he came to me and said, “Why did you make a threatening gesture to my servant when you saw him this morning?” “That was not a threatening gesture,” I said, “it was only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Baghdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.”1 The atmosphere of inevitability—most importantly meeting or avoiding death—pervades the Iliad. One encounter seemingly intertwined 1 As told by W. Somerset Maugham, facing the title page of O’Hara 1952. -

University Microfilms International

ANCIENT EUBOEA: STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF A GREEK ISLAND FROM EARLIEST TIMES TO 404 B.C. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vedder, Richard Glen, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 05:15:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290465 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

From the Walls of Troy to the Canals of Venice Landmarks of Mediterranean Civilizations

FROM THE WALLS OF TROY TO THE CANALS OF VENICE Landmarks of Mediterranean Civilizations Private-Style Cruising Aboard the 50-Suite Corinthian September 12 – 23, 2013 Dear Traveler, From mythic prehistoric sites to magnificent Greek and Roman monuments, the Mediterranean features layer upon layer of history and culture set beautifully upon azure waters. Centuries of history imbue these shores, from ancient structures that remain remarkably intact to beautiful seaside walled towns that have retained their original character and architecture. And it was in these storied shores that our Western tradition was born. After the summer crowds have thinned, join us on a singularly unique cruise that is anchored between two historic cities of the sea, Istanbul and Venice. Each day you will revel in new vistas, historic and natural. Our voyage begins in Turkey—from the splendors of Istanbul to the walls of Troy and the magnificent monuments of Ephesus. Leaving the Anatolian coast, we journey to Crete, Zeus’s birthplace and home to the Labyrinth of the Minotaur at the remarkable palace of King Minos at Knossos. From here, Corinthian voyages to Syracuse in Sicily, one of the most important classical city-states, described by Cicero as the most beautiful of all Greek cities. Onward we travel to Otranto—once a Byzantine stronghold—on into the Adriatic, discovering back-to-back UNESCO World Heritage site ports in Montenegro and Croatia, and ending our journey in Venice, one of the world’s most remarkable cities. As our guides to the ancient cultures and empires we will encounter, we are privileged to have with us two renowned experts. -

The Ovidian Soundscape: the Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses

The Ovidian Soundscape: The Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses Sarah Kathleen Kaczor Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Sarah Kathleen Kaczor All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Ovidian Soundscape: The Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses Sarah Kathleen Kaczor This dissertation aims to study the variety of sounds described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and to identify an aesthetic of noise in the poem, a soundscape which contributes to the work’s thematic undertones. The two entities which shape an understanding of the poem’s conception of noise are Chaos, the conglomerate of mobile, conflicting elements with which the poem begins, and the personified Fama, whose domus is seen to contain a chaotic cosmos of words rather than elements. Within the loose frame provided by Chaos and Fama, the varied categories of noise in the Metamorphoses’ world, from nature sounds to speech, are seen to share qualities of changeability, mobility, and conflict, qualities which align them with the overall themes of flux and metamorphosis in the poem. I discuss three categories of Ovidian sound: in the first chapter, cosmological and elemental sound; in the second chapter, nature noises with an emphasis on the vocality of reeds and the role of echoes; and in the third chapter I treat human and divine speech and narrative, and the role of rumor. By the end of the poem, Ovid leaves us with a chaos of words as well as of forms, which bears important implications for his treatment of contemporary Augustanism as well as his belief in his own poetic fame. -

Polyphemus in Pastoral and Epic Poetry Grace Anthony Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Honors Theses Classical Studies Department 5-2017 The aC nnibal’s Cantations: Polyphemus in Pastoral and Epic Poetry Grace Anthony Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_honors Recommended Citation Anthony, Grace, "The aC nnibal’s Cantations: Polyphemus in Pastoral and Epic Poetry" (2017). Classical Studies Honors Theses. 6. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_honors/6 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Cannibal’s Cantations: Polyphemus in Pastoral and Epic Poetry Grace Anthony A DEPARTMENT HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT TRINITY UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR GRADUATION WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS April 17, 2016 Dr. Corinne Pache, Thesis Advisor Dr. Larry Kim, Department Chair Dr. Tim O’ Sullivan, VPAA Student Agreement I grant Trinity University (“Institution”), my academic department (“Department”), and the Texas Digital Library (“TDL”) the non-exclusive rights to copy, display, perform, distribute and publish the content I submit to this repository (hereafter called “work”) and to make the Work available in any format in perpetuity as part of a TDL, Institution or Department repository communication or distribution effort. I understand that once the Work is submitted, a bibliographic citation to the Work can remain visible in perpetuity, even if the Work is updated or removed. -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34 -

Greek Colonization: Small and Large Islands Mario Lombardo

Mediterranean Historical Review Vol. 27, No. 1, June 2012, 73–85 Greek colonization: small and large islands Mario Lombardo Dipartimento di Beni Culturali, Universita` degli Studi del Salento, Lecce, Italy This article looks at the relation between insular identity and colonization, in Greek thought but also in Greek colonial practices; more precisely, it examines how islands of different sizes are perceived and presented in their role of ‘colonizing entities’, and as destinations of colonial undertakings. Size appears to play an important role: there seems to have been a tendency to settle small to medium sized islands with a single colony. Large islands too, such as Corsica and Sardinia, follow the pattern ‘one island – one polis’; the case of Sicily is very different, but even there, in a situation of crisis, a colonial island identity emerged. Similarly, a number of small to medium-sized single- polis islands of the Aegean acted as colonizing entities, although there is almost no mention of colonial undertakings by small and medium-sized Aegean islands that had more than one polis. Multi-polis islands, such as Rhodes or Crete – but not Euboea – are often presented as the ‘collective’ undertakers of significant colonial enterprises. Keywords: islands; insularity; identity; Greek colonization; Rhodes; Crete; Lesbos; Euboea; Sardinia; Corsica; Sicily 1. Islands are ubiquitous in the Mediterranean ecosystem, and particularly in the Aegean landscape; several important books have recently emphasized the important and manifold role played by insular locations in Antiquity.1 As ubiquitous presences in the Mediterranean scenery, islands also feature in the ancient Greek traditions concerning ‘colonial’ undertakings and practices.