Greek Colonization: Small and Large Islands Mario Lombardo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Announcement EBEA Erice Course 2016

Ettore Majorana Foundation and Centre for Scientific Culture (President: prof. Antonino Zichichi) EBI International School of Bioelectromagnetics “Alessandro Chiabrera” Director of the School: prof. Ferdinando Bersani (University of Bologna, Italy) The Centre for Scientific Culture in Erice (Sicily, Italy) is named after the great Italian scientist Ettore Majorana. Antonino Zichichi, the President of the Centre, has said: “At Erice, those who come in order to follow a certain School are called ‘students’, but actually they are young people who have successfully completed their University studies and who come to Erice in order to learn what the new problems are. However, what is distinctive for Erice is the spirit animating all participants: students no less than teachers. The prime objective is to learn. The student listens to the lectures and after that comes the most amusing part: the discussion session.” Topics in Bioelectromagnetics have come to Erice many times in the past, especially in the 1980s, with international courses and workshops on non-ionising radiation, and today many participants of those courses contribute greatly to the development of this research field. Following the request of the European Bioelectromagnetics Association (EBEA) and the Inter-University Centre for the study of the Interaction between Electromagnetic Fields and Biosystems (ICEmB), in 2003 the Ettore Majorana Centre has established a Permanent School of Bioelectromagnetics, named after Alessandro Chiabrera, who is considered as a master by the young -

Southern and Western Sicily, from Siracusa to Erice

Southern and western Sicily, from Siracusa to Erice Sicily is unique and the challenge with organising any visit here is not what to include but what to leave out! After offering our wonderful “Palermo to Taormina tour” through central and northern Sicily, we have finally decided to branch out and explore the ‘other’ Sicily: the remarkable south and west. The first four nights of the tour are in Siracusa. We then drive to Agrigento for two nights before taking a boat to the Egadi Islands, a small archipelago off the western coast where we stay for the next four days. Back on the mainland, the finale is two nights in a lovely new hotel on the edge of Lo Zingaro, Sicily’s first national park. Highlights include: wandering through the lanes and squares of Siracusa; rambling through the gorgeous Anapra Valley; exploring the extraordinary icing-sugar Baroque towns of the south-east; an aperitif on our hotel terrace in Agrigento watching the sun set over the Valley of the Temples; walking along the endless miles of warm sand of the southern beaches; enjoying the dynamic North African heritage of western Sicily; a picnic lunch on-board a private boat on the Egadi Islands; walking along the spectacular coast line of Sicily’s first national park; our visit to silent, misty Erice; and, of course, the Sicilian people themselves! The walks: The walks on this tour follow well marked trails along good paths over generally undulating countryside. They are a combination of coastal and country walks and range from 9 kilometres to 14 kilometres and take 2.5 to 4 hours not including breaks. -

The Charm of the Amalfi Coast

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 28 Travele rs JO URNEY Sorrento The Charm of the Amalfi Coast Inspiring Moments >Travel the fabled ribbon of the Amalfi Coast, a mélange of ice-cream colored facades, rocky cliffs and sparkling sea. >Journey to Positano, a picturesque INCLUDED FEATURES gem along the Divine Coast. Accommodations Itinerary >Relax amid gentle, lemon-scented (with baggage handling) Day 1 Depart gateway city A breezes in beautiful Sorrento. – 7 nights in Sorrento, Italy, at the Day 2 Arrive in Naples | Transfer A >Walk a storied path through the ruins first-class Hotel Plaza Sorrento. to Sorrento of Herculaneum and Pompeii. Day 3 Positano | Amalfi Extensive Meal Program >Discover fascinating history at a world- – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 4 dinners, Day 4 Paestum renowned archaeological including Welcome and Farewell Day 5 Naples museum in Naples. Dinners; tea or coffee with all meals, Day 6 Sorrento plus wine with dinner. >From N eapolitan pizza to savory olive Day 7 Pompeii | Herculaneum oils to sweet gelato , delight in – Opportunities to sample authentic Day 8 Sorrento cuisine and local flavors. sensational regional flavors. Day 9 Transfer to Naples airport and >Experience four UNESCO World depart for gateway city A Your One-of-a-Kind Journey Heritage sites. – Discovery excursions highlight ATransfers and flights included for AHI FlexAir participants. the local culture, heritage and history. Paestum Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Walking is required on many excursions. enhance your insight into the region. – AHI Connects: Local immersion. – Free time to pursue your own interests. -

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia (8th – 6th centuries BCE) An honors thesis for the Department of Classics Olivia E. Hayden Tufts University, 2013 Abstract: Although ancient Greeks were traversing the western Mediterranean as early as the Mycenaean Period, the end of the “Dark Age” saw a surge of Greek colonial activity throughout the Mediterranean. Contemporary cities of the Greek homeland were in the process of growing from small, irregularly planned settlements into organized urban spaces. By contrast, the colonies founded overseas in the 8th and 6th centuries BCE lacked any pre-existing structures or spatial organization, allowing the inhabitants to closely approximate their conceptual ideals. For this reason the Greek colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia, known for their extensive use of gridded urban planning, exemplified the overarching trajectory of urban planning in this period. Over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE the Greek cities in Sicily and Magna Graecia developed many common features, including the zoning of domestic, religious, and political space and the implementation of a gridded street plan in the domestic sector. Each city, however, had its own peculiarities and experimental design elements. I will argue that the interplay between standardization and idiosyncrasy in each city developed as a result of vying for recognition within this tight-knit network of affluent Sicilian and South Italian cities. This competition both stimulated the widespread adoption of popular ideas and encouraged the continuous initiation of new trends. ii Table of Contents: Abstract. …………………….………………………………………………………………….... ii Table of Contents …………………………………….………………………………….…….... iii 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..……….. 1 2. -

Crotone, Twenty Miles of History in the Heart of the Mediterranean…

Crotone, twenty miles of history in the heart of the Mediterranean… 1 The Port of Crotone - Location History, culture, fine food and wines make of Crotone and its neighbouring area a worthwhile stop. Its visitors will discover the ruins of the ancient Greek-Roman settlement and worship place, the Aragonian fortifications and the medieval city centre, testifying 2700 years of history. Crotone is located on the east coast of Calabria, in Southern Italy, just along the route from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian Sea. Moreover, the port of Crotone is situated in front of Greece, with the nearest Greek island being 125 marine miles away. Latitude 39° 05’ N Longitude 17° 08’ E The port of Crotone is approximately 230 marine miles far from Bari 476 marine miles far from Santorini 162 marine miles far from Corfu 253 marine miles far from Palermo 321 marine miles far from Naples 546 marine miles far from Venice 228 km far from Reggio Calabria 250 km far from Taranto There are two airports close to Crotone - Sant’Anna, 16 km (15 mins by car) - Lamezia Terme, 106 km (1h 40min by car) The port is divided into two (adjacent but not communicating) docks known as the “North Dock” and the “South Dock”. The former is used for commercial traffic, opens towards the northwest, and is 200 metres (65.50 ft) wide with a sounding depth of approximately 9 metres (29.50 ft). The latter is designated as a tourist and fishing port, with an opening towards the south-southwest, 50 metres (164 ft) in width, with 2.5-metres sounding depths. -

The Gattilusj of Lesbos (1355—1462). «Me Clara Caesar Donat Leebo Ac Mytilene, Caesar, Qui Graio Praesidet Iraperio'

The Gattilusj of Lesbos (1355—1462). «Me clara Caesar donat Leebo ac Mytilene, Caesar, qui Graio praesidet iraperio'. Corsi apud Folieta The Genoese occupation of Chios, Lesbos, and Phokaia by the families of Zaccaria and Cattaneo was not forgotten in the counting- houses of the Ligurian Republic. In 1346, two years after the capture of Smyrna, Chios once more passed under Genoese control, the two Foglie followed suite, and in 1355 the strife between John Cantacuzene and John V Palaiologos for the throne of Byzantium enabled a daring Genoese, Francesco Gattilusio, to found a dynasty in Lesbos, which gradually extended its branches to the islands of the Thracian sea and to the city of Ainos on the opposite mainland, and which lasted in the original seat for more than a Century. Disappointed in a previous attempt to recover his rights, the young Emperor John V was at this time living in retirement on the island of Tenedos, then a portion of the Greek Empire and from its position at the mouth of the Dardanelles both an excellent post of obserration and a good base for a descent upon Constantinople. During his so- journ there, a couple of Genoese galleys arrived, commanded by Fran- cesco Gattilusio, a wealthy freebooter, who had sailed from his native oity to onrvp rmt for himself, annidst the confusion of the Orient, a petty principality in the Thracian Chersonese, äs others of his compa- triots had twice done in Chios, äs the Venetian nobles had done in the Archipelago 150 years earlier. The Emperor found in this chance visi- tor an Instrument to effect his own restoration; the two men came to terms, and John V promised, that if Gattilusio would help him to recover his throne, he would bestow upon him the hand of his sister Maria — an honour similar to that conferred by Michael VIII upon Benedetto Zaccaria. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

CEPR European Conference on Household Finance 2018 WELCOME GUIDE Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] The Conference Venue Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Grand Hotel Ortigia https://www.grandhotelortigia.it/ Des Etrangers http://www.desetrangers.com/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Hotel Accommodation Palazzo Gilistro https://www.palazzogilistro.it/ Hotel Gutkowski http://www.guthotel.it/ Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] Transport Catania Airport Fontanarossa http://www.aeroporto.catania.it/ Train Station Siracusa https://goo.gl/6AK4Ee Ortygia Business School Via Roma, 124 96100 Siracusa +39 0931 69510 www.ortygiabs.org [email protected] 1 – The Greek theatre Impressive, solemn, intriguing, with stunning views. It may happen that, while sitting on the big stone steps , you hear the voices of the great Greek heroes, Agamemnon, Medea or Oedipus, even if there are no actors on the stage …this is such an evocative place! It keeps evidences of several historic periods, from the prehistoric ages to Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era. The Greek Theatre is one of the biggest in the world, entirely carved into the rock. In ancient times it was used for plays and popular assemblies, today it is the place where the Greek tragedies live again through the Series of Classical Performances that take place every year thanks to the INDA, National Institute of Ancient Drama. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

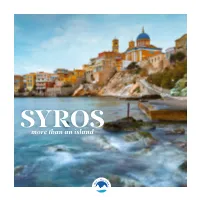

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

An Introduction to the Knowledge of Greek Grammar

AN * INTRODUCTION TO THE KNOWLEDGE or GREEK GRAMMAR. By SAMUEL B. WYLIE, D. D. IN THE WICE PROVOST AND PROFESSOR of ANCIENT LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA. *NWTIET 16). <e) - \ 3} f) iſ a t t I pi} f a, J. whet HAM, 144 CHES NUT STREET. 1838. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1838, by SAMUEL B. Wylie, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. ANDov ER, MAss. Gould & Newman, Printers. **'. … Tº Co PR E FA C E. CoNSIDERING the number of Greek Grammars, already in market, some apology may appear necessary for the introduction of a new one. Without formally making a defence, it may be remarked, that subjects of deep interest, need to be viewed in as many different bearings as can readily be obtained. Grammar, whether considered as a branch of philological science, or a system of rules subservient to accuracy in speaking or writing any language, embraces a most interesting field of research, as wide and unlimited, as the progres sive development of the human mind. A work of such magnitude, requires a great variety of laborers, and even the humblest may be of some service. Even erroneous positions may be turned to good account, should they, by their refutation, contribute to the elucida tion of principle. A desire of obtaining a more compendious and systematic view of grammatical principles, and more adapted to his own taste in order and arrangement, induced the author to undertake, and gov erned him in the compilation of this manual. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1.