Navigating the Political Divide: Lessons from Lincoln,” on April 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-Creation of the Tribal Identity On

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican Contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 By Kumiko Noguchi B.A. (University of the Sacred Heart) 2000 M.A. (Rikkyo University) 2003 Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Native American Studies in the Office of Graduate Studies of the University of California Davis Approved Steven J. Crum Edward Valandra Jack D. Forbes Committee in Charge 2009 i UMI Number: 3385709 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3385709 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Kumiko Noguchi September, 2009 Native American Studies From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 Abstract The main purpose of this study is to show the path of tribal development on the Tule River Reservation from 1776 to 1936. It ends with the year of 1936 when the Tule River Reservation reorganized its tribal government pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. -

Ford, Kissinger, Edward Gierek of Poland

File scanned from the National Security Adviser's Memoranda of Conversation Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library MEMORANDUM THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON ~:p1NODIS MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: President Gerald R. Ford Edward Gierek, First Secretary of the Central Com.mittee of the Polish United Workers' Party Stefan 01szowski, Minister of Foreign Affairs Dr. Henry A. Kissinger, Secretary of State and Assistant to the President Lt. General Brent Scowcroft, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Ambassador Richard T. Davies, US Amb. to Poland Polish Interpreter DATE AND TIME: Tuesday, October 8, 1974 11 :00 a. m. - 12:40 p. m. PLACE: The Oval Office The White House [Ge~eral Scowcroft missed part of the opening conversation. ] Gierek: In France, the ethnic group of Poles came during the French Revolution. People of Polish extraction have been introduced into many countries. Kissinger: Then in the 19th Century, the Polish nationalists concluded that the only way they could get independence was to join every war -- individually. Gierek: Secretary Kissinger knows our history very well. In our anthem, it says we have been guided by Bonapartist methods of how to win. We Socialists left it in. Kissinger: I have always been impressed by Warsaw's Old City. It took much pride to restore it that way. Gierek: That is true. ~/NODIS 9'!ii............ tmCLASSIFJBI) -~\.. B.O. 1295S, Sec. 3.S NSC lfQJDo, lln419S, State Dept. Guidelines 11 t!t=. , NARA, Date d,,'e -2 President: Let me at the outset welcome you in a personal way. I really look forward to your mission and what has been done to bring us together as peoples and what we can do in the future to expand our contacts. -

Giant Sequoia Management in National Parks 1

in: Aune, rnuip s., teen, coora. iyy*. rroceeainss oi me symposium on uian. sc^uiaa. '«'" ^.o^c ... the ecotystea and society; 1992 June 23-25; Visalia, CA. Albany, CA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: 109-115. Objects or Ecosystems? PUB #267 Giant Sequoia Management in National Parks 1 David J. Parsons2 Abstract: Policies and programs aimed at protecting giant sequoia the effects of such external threats as air pollution and (Sequoiadendron giganteum) in the national parks of the Sierra Nevada projected human induced climadc change. The challenges have evolved from the protection of individual trees to the preservation of entire ecosystems. We now recognize that the long-term preservation of associated with assuring the long-term preservation of giant giant sequoia depends on our ability to minimize and mitigate the influences sequoia have become increasingly complicated as we have of human activities. National Park Service management strategies for giant learned more about the complexity and inter-relatedness of sequoia focus on the restoration of native ecosytem processes. This includes the greater Sierra Nevada ecosystem. the use of prescribed fire to simulate natural ignitions as well as the movement of visitor facilities out of the groves. Basic research is being This paper briefly reviews the history of giant sequoia carried out to improve our understanding of the factors infuencing giant management in the National Parks of the Sierra Nevada, sequoia reproduction, growth, and survival. Future management decisions emphasizing a gradually improved understanding of giant must recognize that giant sequoia are only part of a complex ecosystem; they sequoia ecosystems and how management has attempted to cannot be managed as objects in isolation of their surroundings. -

Talk Radio Hits the Airwaves in Iowa, Talking About Immigration As The

Talk Radio Hits the Airwaves in Iowa, Talking About Immigration As the year drew to a close, talk radio once again became the focal point of the national debate about immigration policy, as the nation’s political attention was focused on Iowa. Twenty-two talk radio hosts from Iowa and around the nation came to Des Moines to discuss immigration in advance of the first-in-the-nation presidential caucuses, held on January 3. See page 3 FAIR Cost Study Reveals Why Immigration Is a Top Concern in Iowa Many in the national media expressed surprise that immigration was at the top of the list of concerns among Iowa voters. However, a new report, The Costs of Illegal Immigration to Iowans, released by FAIR in late December, demonstrates why people in Iowa, like others around the nation, are growing increasingly alarmed about the failures of our nation’s immigration policies. See page 4 Illegal Alien Advocacy Network Tries, and Fails, to Keep Iowa 2007 Talk Radio Row Off the Air When the pro-amnesty lobby learned about Iowa 2007 Talk Radio Row, and the release of a new FAIR report on the costs of illegal immigration in Iowa, a well-funded coalition of organizations mounted a smear campaign aimed at preventing the event from taking place. See page 5 Live from Iowa 2007, Talk Radio Row Iowa 2007 Talk Radio Row was conceived as a forum for people in Iowa and all across the country to hear America’s leaders discuss their vision of U.S. immigration policy. National and local leaders were invited to appear on any or all of the talk shows broadcasting from Radio Row. -

Contention Between Communalist and Capitalist Inhabitants Escort to the Cold War

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 4 No 2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Published by MCSER-CEMAS-Sapienza University of Rome May 2013 Contention Between Communalist and Capitalist Inhabitants Escort to the Cold War Dr. Abdul Zahoor Khan, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Department of History & Pakistan Studies Faculty of Social Sciences, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan, Phone Office: +92-51-9019517, Cell: +92-300-5527644, +92-300-7293535 Emails: [email protected], , [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n2p437 Abstract: In retrospect, the question, (what was the cold war about?), seems to a great extent harder to answer than it probably did to contemporaries, some of whom would probably shake their head in wonderment at the above analysis. Yet if we address each of its putative justifications singly, any clear answer seems to fade into the ether. First, from the U.S. side, was the cold war about fighting communism? As long as the Soviet Union remained the sole Communist state, this was a fairly simple proposition, because communism and Russian/Soviet power amounted to the same thing. After 1948, however, with the emergence of independent centers of Communist power in Yugoslavia and then in China, the ideological simplicity of the cold war disappeared. The United States found itself supporting communism in its national variety precisely in order to complicate the projection of Soviet power. The Yugoslav case has been mentioned; and although the U.S. opening to China would be delayed by two, decades of tragic ideological blindness, the United States did undertake, after 1956, to encourage and cultivate national communism in Eastern Europe in the form of the policy of differentiation. -

Representations of Social Media in Popular Discourse

REPRESENTATIONS OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN POPULAR DISCOURSE REPRESENTATIONS OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN POPULAR DISCOURSE By PAMELA INGLETON, B.A. (Hons), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Pamela Ingleton, December 2017 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (English and Cultural Studies) TITLE: Representations of Social Media in Popular Discourse AUTHOR: Pamela Ingleton, B.A. (Hons) (Queen’s University), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: ix, 248 ii Lay Abstract This sandwich thesis of works published from 2010 – 2017 considers how we talk and write about social media in relation to a variety of other concerns: authorship and popular fiction, writing and publishing, archives and everyday life, celebrity and the opaque morality of media promotion. The project addresses social networking platforms (primarily Twitter and Facebook) and those who serve and critique their interests (authors, readers, academics, “everyday people,” national archives, celebrities and filmmakers), often focusing on the “meta” of the media they take as their focus: “extratexts,” reviews and interviews, tweets about books and books about tweets, critical reception, etc. By examining writing on and about social media, this work offers an alternative, context-specific approach to new media scholarship that, in its examination of things said and unsaid, will help inform our contemporary understanding of social media and, by extension, our social media experience. iii Abstract This sandwich thesis of works published from 2010 – 2017 takes up the discursive articulation of “social media” as a mobilizing concept in relation to a variety of other concerns: authorship and popular fiction, writing and publishing, archives and everyday life, celebrity and the opaque morality of media promotion. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

The Birthplace of Hockey Adam Gopnik Traces the Montreal Roots of Our Greatest Winter Sport

McG NeALUMw NI MAGAsZINE Moments that changed McGill McGill Daily turns 100 Anne-France Goldwater : arbitre vedette The birthplace of hockey Adam Gopnik traces the Montreal roots of our greatest winter sport FALL/WINTER 20 11 publications.mcgill.ca/mcgillnews “My“My groupgroup ratesrates savedsaved meme a lotlot ofof money.”moneyy..” – Miika Klemetti, McGill graduate Satisfied client since 2008 Insurance program recommended by the SeeSee howhow goodgood youryour quotequote cancan be.be. At TD Insurance Meloche Monnex, we know how important it is to save wherever you can. As a member of the McGill Alumni Association, you can enjoy preferred group rates and other exclusive privileges, thanks to ourour partnership with your association. You’ll also benefit fromom great coverage and outstanding service. At TD Insurance, we believe in making insurance easy to understand so you can choose your coverage with confidence. GetGet anan onlineonline quotequote atat www.melochemonnex.com/mcgillwww.melochemomonnex.com/mcgill oror callcall 1-866-352-61871-866-352-6187 MondayMonday toto Friday,Friday, 8 a.m.a.m. toto 8 p.m.p.m. SSaturday,aturday, 9 aa.m..m. ttoo 4 pp.m..m. The TD Insurance Meloche Monnex home and auto insurance pprogramg is underunderwritten byy SECURITY NAATIONALTIONAL INSURANCEINSURANCE COMPANY. The program is distributed by MelocheMeloche Monnex Insurance and Financial Services Inc. in Quebecebec and by Meloche Monnex Financiall Services Inc. in the rest off Canada. Due to pprovincial legislation,g our auto insurance program is not offered in British Coolumbia, Manitoba or Saskatchewan. *No purchaseh required.d Contest endsd on January 13, 2012. -

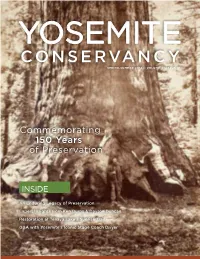

Yosemite Conservancy Spring.Summer 2014 :: Volume 05.Issue 01

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY SPRING.SUMMER 2014 :: VOLUME 05.ISSUE 01 Commemorating 150 Years of Preservation INSIDE An Enduring Legacy of Preservation Expert Insights from Ken Burns & Dayton Duncan Restoration at Tenaya Lake’s Sunrise Trail Q&A with Yosemite’s Iconic Stage Coach Driver PHOTO: (RIGHT) © ROBERT PEARCE. PEARCE. (RIGHT) © ROBERT PHOTO: MISSION Providing for Yosemite’s future is our passion. We inspire people to support projects and programs that preserve and protect Yosemite National Park’s resources and enrich the visitor experience. PRESIDENT’S NOTE YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL MEMBERS Yosemite’s CHAIR PRESIDENT & CEO Philip L. Pillsbury, Jr.* Mike Tollefson* 150th Anniversary VICE CHAIR VICE PRESIDENT, Bob Bennitt* CFO & COO hroughout the years, I have been Jerry Edelbrock privileged to hear countless stories of Yosemite’s life-changing power. For COUNCIL some, Yosemite provides the backdrop Hollis & Matt Adams Jean Lane for generations of family memories. For Jeanne & Michael Adams Walt Lemmermann* others, that first glimpse of Tunnel View Lynda & Scott Adelson Melody & Bob Lind* inspired a career devoted to protecting wild Gretchen Augustyn Sam & Cindy Livermore Susan & Bill Baribault Anahita & Jim Lovelace places. This year’s celebration of the 150th Meg & Bob Beck Lillian Lovelace anniversary of the signing of the Yosemite Suzy & Bob Bennitt* Carolyn & Bill Lowman Grant Act provides an opportunity to reflect David Bowman & Sheila Grether-Marion Gloria Miller & Mark Marion on how Yosemite inspires all of us — and how we can protect it for the future. Tori & Bob Brant Kirsten & Dan Miks Marilyn & Allan Brown Robyn & Joe Miller On June 30, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed a law to forever preserve Steve & Diane Ciesinski* Dick Otter Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias. -

Winter: Five Windows on the Season PDF Book

WINTER: FIVE WINDOWS ON THE SEASON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Adam Gopnik | 256 pages | 27 Sep 2011 | House of Anansi Press | 9780887849756 | English | Toronto, Canada, Canada Winter: Five Windows on the Season PDF Book Americans in Paris Amazon. Shelves: arts-literat-classics. I don't know where I came across this title, but I'm very glad I did. I need to read this at least twice more to absorb the layers of this dense text. We aim to create a safe and valuable space for discussion and debate. Much of Gopnik's quest is rooted in the joy of his own childhood imagination: if there were a heaven, he suggests, for him it would perpetually be 19 December; school is out, coloured lights are in the shops, there is ice underfoot and Christmas a week away. We use cookies to serve you certain types of ads , including ads relevant to your interests on Book Depository and to work with approved third parties in the process of delivering ad content, including ads relevant to your interests, to measure the effectiveness of their ads, and to perform services on behalf of Book Depository. Stafford Beer. He had previously authored several books on different topics, the most successful being Paris to the Moon , a collection of essays published in Performance and Analytics. That's pretty much my only complaint with this book. Adam Gopnik has been contributing to The New Yorker since A delightful, insightful, often humourous investigation into the modern Western idea of winter: what is the season, what does it mean to us, what has it meant to us in the past. -

Extensions of Remar.Ks

July 8, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 23329 EXTENSIONS OF REMAR.KS BRIGHT FUTURE FOR NORTHEAST the Commonwealth, the Department of Com With a good reputation for action it is diffi ERN PENNSYLVANIA munity Affairs and the Department of Com cult to slow the momentum of a winner. merce wm benefit the northeast and other And it has not been done With magic, With regions as they work in the seventies. rabbits in a ha.t--not by any one local, state HON. HUGH SCOTT Once a Bureau within the Department of or federal agency, but with the combined ef Commerce, the Department of Community forts of responsible people, hardworking, OF PENNSYLVANIA Affairs has blossomed into an effective backed by substantial private investment- IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES agency for direct involvement in vital areas with faith, dimes, dollars, of people who be Wednesday, July 8, 1970 that have mushroomed into prominence in lieved it could be done. recent years. I believe it is an unheralded Specifically, the pace was set Dy successful Mr. SCO'IT. Mr President, on June 6, blessing for the citizens of the Common industrial expansion and relocation pro 1970, the secretary of commerce of Penn wealth of Pennsylvania to have such close grams. PIDA activity in a seven county area sylvania, Hon. William T. Schmidt, de cooperation and such common dedication of northeastern Pennsylvania resulted in 241 livered a speech to the conference of the among the personnel of two organiz.a.tions loans in the amount of $58,760,000 since 1956 that can provide so much assistance to them. -

Modes of Adaptation and Appropriation in the Hogarth Shakespeare Series

Trabajo de Fin de Máster en Estudios Literarios y Culturales Ingleses y su Proyección Social Modes of Adaptation and Appropriation in the Hogarth Shakespeare Series Autor: Mario Giménez Yuste Tutora: Dra. Marta Cerezo Moreno Facultad de Filología UNED Convocatoria general: junio 2019 Curso: 2018-19 Modes of Adaptation and Appropriation in the Hogarth Shakespeare Series Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................. 4 2.1. Adaptation and Appropriation ................................................................................... 4 3. The Hogarth Series .................................................................................................... 14 3.1. Critical Reception ..................................................................................................... 14 3.2. A Brief Consideration of the Seven Novels ............................................................... 16 3.3. Selection Criteria ...................................................................................................... 20 4. The Chosen Novels ........................................................................................................ 21 4.1. Dunbar ...................................................................................................................... 21 4.1.1. Critical Reception .............................................................................................