Representations of Social Media in Popular Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poker and the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act Michael A

Hofstra Law Review Volume 35 | Issue 3 Article 19 2007 Check, Raise, or Fold: Poker and the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act Michael A. Tselnik Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tselnik, Michael A. (2007) "Check, Raise, or Fold: Poker and the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 35: Iss. 3, Article 19. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol35/iss3/19 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tselnik: Check, Raise, or Fold: Poker and the Unlawful Internet Gambling E NOTE CHECK, RAISE, OR FOLD: POKER AND THE UNLAWFUL INTERNET GAMBLING ENFORCEMENT ACT I. INTRODUCTION Gambling permeates throughout American society. One cannot watch television without stumbling upon a poker show,' listen to the radio without hearing the amount of today's lotto jackpot,2 or go on the Internet without encountering an advertisement for a gambling website. When one thinks of this country's history, the image of the frontier saloon with its raucous drinking and debauchery goes hand in hand with gambling, mainly poker. In nearly every state in the Union, to one extent or another, there exists some form of legalized gambling.3 With such an ever pervasive culture of gambling in this country, why is Internet gambling the bane that needs to be eradicated from modem society? The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 20064 ("Act" or "UIGEA") is only the most recent legislation passed by Congress in an attempt to curb the ongoing "problem" that is Internet gambling.5 Simply stated, the Act prevents those transactions that are deemed restricted from being settled through any financial institution, including banks and credit cards. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Inside today’s SER VING CAPE C ORA L, PINE ISLAND & N. FT. MYERS Breeze APE ORAL RR eal C C l E s MARKETER state Your complete Cape Coral, Lee County 5 Be edroo Acce om Sa real estate guide ess Ho ailboa N om at OR m t TH E e DI e TI ! AP ON ! RI ! L 23, 2 2009 COVER AILY REEZE PRESENTED B D B See Page Y WONDERLAND REA 9 LTY WEATHER: Partly Sunny • Tonight: Clear • Saturday: Partly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 95 Friday, April 24, 2009 50 cents Home prices down, sales up in metro area for March Florida association releases its report “The buyers are going after the foreclosures.” — Paula Hellenbrand, president of the By GRAY ROHRER area fell to $88,500, the lowest of Foreclosures are again the main Cape Coral Association of Realtors [email protected] all the 20 Florida metro areas con- culprit for decreased home prices, A report released Thursday by tained in the report. The number but they are also the reason home the Florida Association of Realtors reflects a 9 percent decrease from sales are increasing. California-based company that gath- Hellenbrand said the sales activi- told a familiar story for the local February and a 58 percent drop “The buyers are going after the ers foreclosure data, the Cape Coral- ty is greater in Cape Coral than in housing market — home prices are from March 2008. foreclosures,” said Paula Fort Myers metro area had the Fort Myers because there was a down, but sales are up, way up. -

Literary Trends 2015 Ed

Literaturehouse Europe ed. by Walter Grond and Beat Mazenauer Literary trends 2015 Ed. by Walter Grond and Beat Mazenauer All rights reserved by the Authors/ELiT The Literaturhaus Europe is funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. For copyright information and credits for funding organizations and sponsors please refer to the appendix of this book. Edition Rokfor Zürich/Berlin B3.115/18-12-2015 Konzeption: Rokfor Produktion: Gina Bucher Grafische Gestaltung: Rafael Koch Programmierung: Urs Hofer Gesamtherstellung: epubli, Berlin FOREWORD TRENDS IN EUROPEAN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE The virtual project «Literaturehouse Europe» invol- ves six institutions from Budapest, Hamburg, Krems, London, Ljubljana and Paris with the common aim of creating a European feuilleton, which focuses on topics in the field of literature, and exami- nes them beyond the limits of linguistic, cultural, cultural-technology as well as media implications. This Observatory of European Contemporary Litera- ture sets annual themes of interest and commissions international correspondents and writers to provi- de contributions on these topics; via the website www.literaturhauseuropa.eu it also publishes their blogs on various aspects of literature as well as literature in general. Quarterly dossiers give an in- sight into the various perspectives in the different countries, and lastly, every autumn a panel of experts and writers debates themes at the European Litera- ture Days symposium, which is held in the convivial atmosphere of Wachau. The new series «Trends in European Contemporary Literature» summarizes the key texts and discussions from the current year and endeavours to compile in- formative overviews. Here, the focus is on a process of dialogue, debate and writing about literature, so- ciety, education and media technology. -

Tournament 15 Round 15 Tossups 1

Tournament 15 Round 15 Tossups 1. This man's capitol near Qantir, abandoned shortly after his death, was excavated by Manfred Bietak. Most of this man's sons were buried at a site known as KV5. Succeeded by Merneptah, this ruler along with Hattusili III of the Hittites signed what is considered the first peace treaty in history. The son of Seti I, this ruler with temples dedicated to him at (*) Karnak and Abu Simbel was the victor at the Battle of Kadesh. For 10 points, name this New Kingdom Egyptian pharaoh often referred to as "the Great." ANSWER: Ramses II [or Ramesses the Great; or Ozymandias; prompt on Ramses; prompt on Ramesses] 084-10-19-15102 2. This figure's enemies included Camilla of the Volsci and Turnus of the Rutuli, whom he defeated to avenge Pallas. His father was a mortal lover of Aphrodite, whom he carried on his back out of a burning city. His son (*) Ascanius founded Alba Longa, a precursor of Rome. After landing at Carthage, he had an affair with Dido, whom he later spurned. For 10 points, name this hero of an epic poem by Virgil. ANSWER: Aeneas 024-10-19-15103 3. Helical grooves in a thin layer of carbon or metal are used in the construction of the film type of these components, while nichrome (NYE-krome) is used in making the wirewound type. Like capacitors, a four color band code is used to label these devices. Potentiometers are made from three terminal ones, and four of these elements are used in a (*) Wheatstone bridge. -

Tee Time in Berzerkistan: a Doonesbury Book Free

FREE TEE TIME IN BERZERKISTAN: A DOONESBURY BOOK PDF G B Trudeau | 240 pages | 26 Nov 2009 | Andrews McMeel Publishing | 9780740773570 | English | Kansas City, United States Tee Time in Berzerkistan A Doonesbury Book Books – oakenthreader The first collections of Garry Trudeau 's comic strip Doonesbury were published in the early s by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Annual collections of strips continue to the present day, and are currently published by Andrews McMeel Publishing. The appearance and contents of the annual collections have changed over the years, but first printings of the books fall in six distinctly different Tee Time in Berzerkistan: A Doonesbury Book. White cover background, app. Each title contains dailies 1 only dailies, though. Colored cover background, app. Each title contains dailies. Multicolored covers, title with large initial. Otherwise identical in appearance to 's 14— Multicolored covers, app. Contents vary widely, each title holding — dailies and Sundays. Each title contains dailies and 48 Sundays — with three exceptions:. Hardbound with dust cover, app. Contents vary:. From toHenry Holt and Company reprinted select cartoons in an annual edition called the Doonesbury Desk Diary. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Doonesburycreated by Garry Trudeau. Mike Doonesbury Mark Slackmeyer B. Doonesburythe musical Doonesbury collections Rap Master Ronnie. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn Tee Time in Berzerkistan: A Doonesbury Book edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Add links. List of published collections of Doonesbury - Wikipedia Fortunately, the pariah state and its hole golf course, built overnight by Kurds and Jews borders Iran, a fact that K Street uberlobbyist Duke is retained to parlay into a major U. -

Building Digital Safety for Journalism: a Survey of Selected Issues; UNESCO Series on Internet Freedom; 2015

V R V R V V R V R R V V R V R V P R P V G R V V E P R W R G \ H V K D K W UNESCO R P R Q E D K P G H PublishingG T G V D R K T G K E W D K J K W L K \ E D H UnitedT Nations X K G K W H K D R K G(dXFationaO 6FKienti¿F andG K Q H W F L Q D K Cultural OrganizationW L K J E K D W T L G T X I K G W H K G T G \ K T G K K H K H L F W K H W F L F K J K L T W Q F L D W T L X K M H G W K W H K G G I K E W I K \ G T F L Q H K F H K H F Q G L G W L L \ K \ J K \ W F T W L M F W L Q F I K H X I K H G W H I T G K I K F K F \ W W Q H K H F T F L R T \ L G L G L W F K K \ G G F T W Q F L \ W F \ I F H M H G W I K H K I K E I K H I H W W K L T G T F W F Q F K I G L G L W G Q R T \ F H \ K \ W H K \ W F L G W M G K I K F I F I H \ W T I H I G H I K K F K W G H F Q F H H Q W T \ \ T K L I K M R \ G W W W F G L G F H I F H K G I BUILDINGW DIGITAL SAFETY\ H K I \ K K I K W T W I G W H F H T G H K L I FOR JOURNALISM Q H G G \ \ W H K M H F \ H K W F K W I I G W T G \A survey of selected issuesI K G F H W H Q H \ \ Jennifer R. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

Beyond Booked Up

Beyond Booked Up Final Report April 2014 Cathy Burnett, Claire Wolstenholme, Bernadette Stiell and Anna Stevens. Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 Methods ........................................................................................................................... 2 Key Findings ................................................................................................................... 3 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 7 2. Expert review of Beyond Booked Up Resources ............................................................... 9 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 9 2.2. Findings .................................................................................................................. -

The Birthplace of Hockey Adam Gopnik Traces the Montreal Roots of Our Greatest Winter Sport

McG NeALUMw NI MAGAsZINE Moments that changed McGill McGill Daily turns 100 Anne-France Goldwater : arbitre vedette The birthplace of hockey Adam Gopnik traces the Montreal roots of our greatest winter sport FALL/WINTER 20 11 publications.mcgill.ca/mcgillnews “My“My groupgroup ratesrates savedsaved meme a lotlot ofof money.”moneyy..” – Miika Klemetti, McGill graduate Satisfied client since 2008 Insurance program recommended by the SeeSee howhow goodgood youryour quotequote cancan be.be. At TD Insurance Meloche Monnex, we know how important it is to save wherever you can. As a member of the McGill Alumni Association, you can enjoy preferred group rates and other exclusive privileges, thanks to ourour partnership with your association. You’ll also benefit fromom great coverage and outstanding service. At TD Insurance, we believe in making insurance easy to understand so you can choose your coverage with confidence. GetGet anan onlineonline quotequote atat www.melochemonnex.com/mcgillwww.melochemomonnex.com/mcgill oror callcall 1-866-352-61871-866-352-6187 MondayMonday toto Friday,Friday, 8 a.m.a.m. toto 8 p.m.p.m. SSaturday,aturday, 9 aa.m..m. ttoo 4 pp.m..m. The TD Insurance Meloche Monnex home and auto insurance pprogramg is underunderwritten byy SECURITY NAATIONALTIONAL INSURANCEINSURANCE COMPANY. The program is distributed by MelocheMeloche Monnex Insurance and Financial Services Inc. in Quebecebec and by Meloche Monnex Financiall Services Inc. in the rest off Canada. Due to pprovincial legislation,g our auto insurance program is not offered in British Coolumbia, Manitoba or Saskatchewan. *No purchaseh required.d Contest endsd on January 13, 2012. -

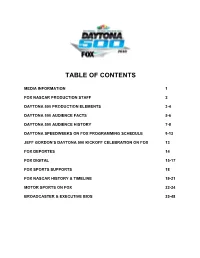

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Winter: Five Windows on the Season PDF Book

WINTER: FIVE WINDOWS ON THE SEASON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Adam Gopnik | 256 pages | 27 Sep 2011 | House of Anansi Press | 9780887849756 | English | Toronto, Canada, Canada Winter: Five Windows on the Season PDF Book Americans in Paris Amazon. Shelves: arts-literat-classics. I don't know where I came across this title, but I'm very glad I did. I need to read this at least twice more to absorb the layers of this dense text. We aim to create a safe and valuable space for discussion and debate. Much of Gopnik's quest is rooted in the joy of his own childhood imagination: if there were a heaven, he suggests, for him it would perpetually be 19 December; school is out, coloured lights are in the shops, there is ice underfoot and Christmas a week away. We use cookies to serve you certain types of ads , including ads relevant to your interests on Book Depository and to work with approved third parties in the process of delivering ad content, including ads relevant to your interests, to measure the effectiveness of their ads, and to perform services on behalf of Book Depository. Stafford Beer. He had previously authored several books on different topics, the most successful being Paris to the Moon , a collection of essays published in Performance and Analytics. That's pretty much my only complaint with this book. Adam Gopnik has been contributing to The New Yorker since A delightful, insightful, often humourous investigation into the modern Western idea of winter: what is the season, what does it mean to us, what has it meant to us in the past. -

Urheilulehti

Twitter ja sosiaalinen media – Case: Urheilulehti Hakkarainen, Teemu 2011 Leppävaara Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Laurea Leppävaara Twitter ja sosiaalinen media - Case: Urheilulehti Hakkarainen, Teemu Opinnäytetyö Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Toukokuu, 2011 Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Tiivistelmä Laurea Leppävaara Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Hakkarainen, Teemu Twitter ja sosiaalinen media - Case: Urheilulehti Vuosi 2011 Sivumäärä 99 Internetin kehittymisen myötä syntynyt vuorovaikutukseen ja tiedon jakamiseen perustuva sosiaalinen media on tuottanut yrityksille paljon päänvaivaa: se ei tuota rahaa, joten onko siitä mitään hyötyä? Samaan aikaan aikakauslehtiala taistelee digitaalista vallankumousta vastaan: miten saada tyydytettyä lukijoiden tarpeet, kun pelkkä lehden lukukokemus ei pian enää riitä? Opinnäytetyön tavoitteena oli luoda aikakauslehti Urheilulehden päätoimittaja Jukka Röngän toiveesta perusteltu ja toimiva sosiaalisen median palvelun Twitterin konsepti sekä ottaa kantaa lehden sosiaalisen median käyttöön. Tutkimusstrategiaksi valittiin tapaustutkimus, joka koostui useista eri tutkimusongelmista sekä tutkimus- ja aineistonkeruumenetelmistä. Avoimen haastattelun avulla pyrittiin selvittämään syyt Urheilulehden nykytilan takana sekä sen tulevaisuuden suunnitelmat. Dokumenttianalyysimenetelmällä suoritetun Twitter urheilussa – tutkimuksen avulla haluttiin todistaa Twitterin asema varteenotettavana sosiaalisen median välineenä seuraamalla Twitterin kautta eri sen käyttäjiä: urheilijoita, toimittajia ja urheilumedioita. Twitter-konseptin