Indian Tv Broadcasting at a Crossroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT: in India Till 1991 There Was Only One Television Channel

ABSTRACT: In India till 1991 there was only one television channel –Doordarshan, the public service broadcaster. With the opening up of the Indian economy in early 1990s enabled the entry of private broadcasters in India. The number of television channels has proliferated manifold. By 2005 India had more than 200 digital channels. The number of television channels has grown from around 600 in 2010 to 800 in 2012.This includes more than 400 news and current affairs channel. Technological changes have caused intense competition in news and general entertainment channels, as a result of which there is growth in regional and niche channels. The growth of cable and satellite television and direct to home television services has continued to drive television as the most preferred medium among advertisers. Broadcasters are also tapping into online and mobile media to increase their revenue. This paper seeks to study the impact of privatisation on media policy of the Government of India and how it has evolved various institutional mechanisms to deal with the growth of television as the medium to study the effect of privatisation and convergence on media regulations as television is the most powerful medium. The visual images transmitted by television reach large section of the Indian population irrespective of linguistic and cultural differences. GROWTH OF THE TELEVISION INDUSTRY IN INDIA: Television began in India in 1959 as an educational project supported by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the Ford Foundation. Television was based on the model of a public broadcasting system prevalent in many countries of Europe. -

Sun TV Network Limited: Rating Reaffirmed Summary of Rating Action

July 01, 2019 Sun TV Network Limited: Rating Reaffirmed Summary of rating action Previous Rated Amount Current Rated Amount Instrument* Rating Action (Rs. crore) (Rs. crore) Short term - Non-fund based 12.50 12.50 [ICRA]A1+; reaffirmed Total 12.50 12.50 *Instrument details are provided in Annexure-1 Rationale The rating reaffirmation draws comfort from STNL’s established presence; strong brand equity of ‘Sun TV’; and the company’s strong financial profile. The company witnessed strong revenue growth of 27.7% in FY2019 supported by healthy growth in subscription and advertisement revenues, and its margins remained strong at an OPM of 68.9% and NPM of 37.5%, aided by its scale, high bargaining power and nil debt position. The company has had zero debt every year, with sizeable cash and liquid investments of Rs. 2,686.5 crore as on March 31, 2019 (PY: Rs,1,896.9), facilitated by its strong accruals. By virtue of ‘Sun TV’ being one of the top viewership channels and having consistently high television rating points (TRP’s), the company has significant bargaining power over its content providers. This, in turn, has aided in control over telecasted content and facilitated advertisement revenue growth. As per the new TRAI order, every customer is entitled to a set free to air channels which may or may not include popular channels offered by major broadcasters. In addition, customers can choose channels/packs offered by the broadcasters based on their interest. However, Sun TV is part of the base pack in its viewership locations by virtue of user preference. -

Media Buzz Large Regional TV Opportunity; Competitive Intensity on the Rise

Asia Pacific | India Media - General (Citi) Industry Focus 5 December 2008 23 pages Media Buzz Large Regional TV Opportunity; Competitive Intensity on the Rise High growth regional entertainment market — The size of the six major regional markets is estimated to be ~Rs 21b, thus contributing about a fourth of the overall Surendra Goyal, CFA1 TV ad revenues in India. Sun TV Network and Zee News are the larger listed players that benefit from the regional entertainment market opportunity. 'Viewership - Revenue' mismatch — The share of advertising revenue for the Aditya Mathur1 regional language channels (~25%) is far less when compared to the viewership share (~37%). Regional advertising is growing at a pace faster than the national Jason Brueschke2 growth. Of the ad revenue pie, ~60% comes from regional ads. Large players enter the regional genre — The market is expanding as the number of corporates with deep pockets enter. Zee News has entered the Tamil, Telugu & Kannada markets while Star has entered the Marathi & Bengali segments and has aggressive plans for South India through its JV with Jupiter Entertainment. Increasing competition results in pressure on content/talent and other costs. Zee News management meeting takeaways — (a) ZEEN expects to grow at least 5% more than overall industry; (b) Zee Telugu broke even in 2QFY09 and mgmt expects Zee Kannada to breakeven by mid CY09; (c) Zee Bangla & Zee Marathi contribute to about half of ZEEN's revenues; (d) In Tamil Nadu, ZEEN targets the No 2 position, after Sun TV, within the next 12-18 months. Noteworthy this month: (1) GEC ratings decline as no fresh content aired...— For ~20 days, Hindi GECs were not airing fresh content, which led to a steep drop in ratings. -

STOXX BRIC 100 Last Updated: 01.08.2017

STOXX BRIC 100 Last Updated: 01.08.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 60.5 1 1 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 50.8 2 2 INE040A01026 B5Q3JZ5 HDBK.BO IN00CH HDFC Bank Ltd IN INR Y 47.7 3 3 INE002A01018 6099626 RELI.BO IN0027 Reliance Industries Ltd IN INR Y 44.4 4 6 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 41.3 5 4 INE001A01036 6171900 HDFC.BO IN00EJ Housing Development Finance Co IN INR Y 37.5 6 7 INE154A01025 B0JGGP5 ITC.BO IN007C ITC Ltd IN INR Y 34.6 7 5 BRITUBACNPR1 B037HR3 ITUB4.SA BR0035 ITAU UNIBANCO HOLDING SA -PREF BR BRL Y 32.7 8 9 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 32.0 9 10 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 31.8 10 8 INE009A01021 6205122 INFY.BO IN006B Infosys Ltd IN INR Y 30.6 11 11 INE090A01021 BSZ2BY7 ICBK.BO IN00BG ICICI Bank Ltd IN INR Y 25.6 12 12 BRBBDCACNPR8 B00FM53 BBDC4.SA BR0079 BANCO BRADESCO SA - PREF BR BRL Y 25.0 13 13 RU0009029540 4767981 SBER.MM EV023 SBERBANK RU RUB Y 23.9 14 14 BRABEVACNOR1 BG7ZWY7 ABEV3.SA BR01UX AMBEV BR BRL Y 23.0 15 15 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 20.0 16 16 INE018A01030 B0166K8 LART.BO IN00AF Larsen & Toubro Ltd IN INR Y 19.3 17 17 INE467B01029 B01NPJ1 TCS.BO IN005A Tata Consultancy Services Ltd IN INR Y 17.3 18 20 INE237A01028 6135661 KTKM.BO IN06Q1 Kotak Mah Bk IN INR Y 16.9 19 22 INE238A01034 BPFJHC7 AXBK.BO IN00MR AXIS BANK IN INR Y 16.4 20 21 CNE1000002Q2 6291819 0386.HK CN0098 China Petroleum & Chemical 'H' CN HKD Y 16.4 21 18 RU0007661625 B59L4L7 GAZP.MM EV019 GAZPROM RU RUB Y 16.2 22 19 BRVALEACNPA3 2257127 VALE5.SA BR10JM VALE S.A. -

In India Till 1991 There Was Only One Television Channel –Doordarshan, the Public Service Broadcaster

The Asian Conference on Media and Mass Communication 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Privatisation,convergence and Broadcasting regulations:A case study of the Indian Television Industry, Padma Rani School of communication;Manipal University, India 0139 The Asian Conference on Media and Mass Communication 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract In India till 1991 there was only one television channel –Doordarshan, the public service broadcaster. With the opening up of the Indian economy in early 1990s enabled the entry of private broadcasters in India. The number of television channels has proliferated manifold. By 2005 India had more than 200 digital channels. The number of television channels has grown from around 600 in 2010 to 800 in 2012.This includes more than 400 news and current affairs channel. Technological changes have caused intense competition in news and general entertainment channels, as a result of which there is growth in regional and niche channels. The growth of cable and satellite television and direct to home television services has continued to drive television as the most preferred medium among advertisers. Broadcasters are also tapping into online and mobile media to increase their revenue. This paper seeks to study the impact of privatisation on media policy of the Government of India and how it has evolved various institutional mechanisms to deal with the growth of television as the medium to study the effect of privatisation and convergence on media regulations as television is the most powerful medium. The visual images transmitted by television reach large section of the Indian population irrespective of linguistic and cultural differences. -

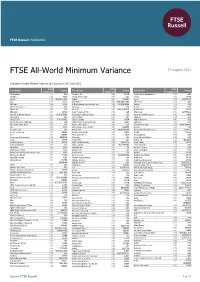

FTSE All-World Minimum Variance

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE All-World Minimum Variance Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index Index Index Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country weight (%) weight (%) weight (%) 3M Company 0.1 USA Ajinomoto Co 0.05 JAPAN Annaly Capital Management 0.07 USA 3M India 0.02 INDIA Akamai Technologies 0.14 USA Anritsu 0.03 JAPAN a2 Milk 0.03 NEW ZEALAND Akbank 0.01 TURKEY Ansell 0.02 AUSTRALIA A2A 0.01 ITALY Akzo Nobel 0.02 NETHERLANDS ANSYS Inc 0.08 USA ABB India 0.04 INDIA Al Rajhi Banking & Investment Corp 0.04 SAUDI ARABIA Anthem 0.08 USA Abbott Laboratories 0.09 USA Albemarle 0.06 USA Aon plc 0.09 USA AbbVie Inc 0.11 USA Alcon AG 0.02 SWITZERLAND Aozora Bank 0.03 JAPAN ABC-Mart 0.03 JAPAN Aldar Properties PJSC 0.02 UAE APA Group 0.02 AUSTRALIA Abdullah Al Othaim Markets 0.04 SAUDI ARABIA Alexandria Real Estate Equity 0.09 USA Apollo Hospitals Enterprise 0.04 INDIA Abiomed Inc 0.11 USA Alexion Pharm 0.12 USA Apple Inc. 0.09 USA Aboitiz Power 0.02 PHILIPPINES Alfresa Holdings 0.02 JAPAN Applied Materials 0.06 USA Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank 0.02 UAE Alibaba Pictures Group (P Chip) 0.02 CHINA Aptiv PLC 0.04 USA Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank 0.03 UAE Align Technology Inc 0.05 USA Arab National Bank 0.03 SAUDI ARABIA ACC 0.04 INDIA Alimentation Couche-Tard B 0.02 CANADA Aramark 0.04 USA Accenture Cl A 0.09 USA Alinma Bank 0.04 SAUDI ARABIA Arca Continental SAB de CV 0.03 MEXICO Accton Technology 0.03 TAIWAN A-Living Services (H) 0.02 CHINA Arcelik 0.01 TURKEY Acer 0.04 TAIWAN Alkem Laboratories -

Awesome Indian TV Guide

Awesome Indian TV Guide Awesome Indian TV Guide 1 / 4 2 / 4 TVPlayer is home to the most popular TV channels and premium quality on-demand programmes, ... Fast N' Loud Revved Up: Cool Customline14:00 - 15:00.. Find your favourite shows and discover upcoming gems in Australia's most accurate and up to date TV Guide. View the latest Griffith TV Guide featuring complete program listings across every TV channel by day, time, genre and channel. ... Parveen's Indian Kitchen. 5:30 PM ... Sensor COOL Bedding. 7:30 PM .... This is the most awesome tv schedule app I ever seen. Proper timings and shows. We can view shows by selecting different generes and lot other cool features.. Find the latest TV show information on all your favourite shows on the ... TV Guide: Thursday 5 March ... 3:30 AM George Clarke's Best of Amazing Spaces. Join Sway Preview I can create one and load it into 'TV Guide' and it shows the listings ... is an awesome program and supports building xml files for Indian EPGs.. ... when your favorite PBS programming is on WJCT TV with our program guide. ... Fiddlesticks After an awesome jig dance at the Tribal Hall, Molly can't wait for ... Faraway: Galactic Escape 1.0.5803 Apk + Mod (Free Shopping) for androie Ofra Cosmetics: Rodeo Drive Collection swatches and thoughts Epubor Ultimate eBook Converter 3.0.11.409 Crack 3 / 4 Watch Indian TV shows, movies, music videos, action packed thrillers, news & more. ... Quote – A collection of awesome quotes and saying from the author. And it's all in one .. -

Company Detail Report

CMP: 573.40 DEC 6th, 2018 SUN TV NETWORKS LTD ISIN: Overweight Result Update (PARENT BASIS): Q2 FY19 INE424H01027 Index Details SYNOPSIS Stock Data Sun TV Network Limited, together with its Sector Broadcasting & Cable TV subsidiaries, engages in producing and BSE Code 532733 broadcasting satellite television and radio software Face Value 5.00 programming in the regional languages of South 52wk. High / Low (Rs.) 1097.05/564.05 India. Volume (2wk. Avg.) 68000 Sun Network Ltd has achieved a turnover of Rs. Market Cap (Rs. In mn.) 225965.47 7495.50 mn for Q2 FY19 as against Rs. 6759.00 mn in Q2 FY18, an increase of 10.90%. Annual Estimated Results(A*: Actual / E*: Estimated) Years (Rs. In mn) FY18A FY19E FY20E During the quarter, EBIDTA stood at Rs. 6160.90 mn as against Rs. 5333.20 mn in the corresponding Net Sales 28624.50 34349.40 39845.30 period of the previous year, up by 15.52%. EBITDA 20991.30 26213.43 30396.10 Net Profit 10930.40 14033.84 16506.03 Profit before tax (PBT) stood at Rs. 5336.30 mn in EPS 27.74 35.61 41.88 Q2 FY19 as against Rs. 4305.70 mn in the corresponding quarter of the previous year, an P/E 20.67 16.10 13.69 increase of 23.94%. Shareholding Pattern (%) During the 2nd quarter, net profit increased by 23.41% to Rs.3513.20 mn from Rs.2846.70 mn in As on Sep 2018 As on Jun 2018 the corresponding period of the previous year. Promoter 75.00 75.00 EPS of the company stood at Rs. -

Hathway Cable & Datacom Companyname

RESULT UPDATE HATHWAY CABLE & DATA COM Broadband ARPU disappoints, cable performance muted India Equity Research| Media COMPANYNAME Hathway Cable & Datacom’s (Hathway) Q4FY18 revenue was in line while EDELWEISS 4D RATINGS EBITDA was below estimates. Key highlights: (i) subscription grew ~3% Absolute Rating HOLD QoQ, aided by cable ARPU increase (up INR4 QoQ in Phase III; up INR3 Rating Relative to Sector Performer QoQ in Phase IV); (ii) net realisation in Phase I and II market remained Risk Rating Relative to Sector Medium stagnant at INR108 and INR102 respectively; and iii) 5.1% QoQ growth in Sector Relative to Market Overweight broadband revenue aided by broadband additions. However the broadband ARPU saw a decline on QoQ basis (710 in Q4 vs 717 in Q3) due to intense competition. We believe the trend of declining broadband MARKET DATA (R: HAWY.BO, B: HATH IN) ARPU will continue going forward because of the intense competition CMP : INR 27 Target Price : INR 30 from Jio and other telecom players. Although the company is aiming for 52-week range (INR) : 49 / 26 cost rationalisation, we believe the benefit arising from it will be offset by Share in issue (mn) : 830.5 higher interest cost because of high debt levels. Increase in Phase III and M cap (INR bn/USD mn) : 22 / 359 IV cable ARPU remains a key monitorable. Factoring the same, we cut Avg. Daily Vol.BSE/NSE(‘000) : 1,713.3 FY19/20E EBITDA by 27.6%/19.9% and also downgrade to ‘HOLD/SP’ from ‘BUY/SP’ with revised TP of INR30 (earlier INR51). -

Master List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels As on 31.10.2018 Sr

Master List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 31.10.2018 Sr. No. Channel Name Name of the Company Category Upliniking/ Language Date of Downlinkin/ Permission Uplinking Only 1 9X 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 24-09-2007 DOWNLINKING 2 9XM 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS HINDI/ENGLISHUPLINKING & /BENGALI&ALL INDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE 24-09-2007LANGUAGE DOWNLINKING 3 9XO (9XM VELVET) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING 4 9X JHAKAAS (9X MARATHI) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & MARATHI 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING 5 9X JALWA (PHIR SE 9X) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI/ENGLISH /BENGALI&ALL 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING INDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 6 Housefull Action (earlier 9X BAJAO 9X MEDIA PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 17-01-2015 (Earlier 9X BAJAAO & 9X BANGLA) DOWNLINKING 7 TV 24 A ONE NEWS TIME BROADCASTING NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI/ PUNJABI/ ENGLISH 21-10-2008 PRIVATE LIMITED DOWNLINKING 8 BHASKAR NEWS (AP 9) A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 DOWNLINKING OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 9 SATYA A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 DOWNLINKING OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 10 Shiva Shakthi Sai TV (earlier BENZE AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING & TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 TV (Earlier AADRI ENRICH) WORKS PVT.LTD. DOWNLINKING AMIL/KANNADA/BENGALI/MALAYALA M 11 Mahua Plus (earlier AGRO ROYAL TV AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING & TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 (Earlier AADRI WELLNESS) WORKS PVT.LTD. -

SUN TV Annual Report 2020

{) SuN TV NETWORK LIMITED Murasoli MaranTowers , 73, MRCNagar Main Road, MRC Nagar , Chennai-600 028 , India. SUN Tel : +91-44-44676767 , Fax: +91-44-40676161 , E-mail:[email protected] GROUP Website:www.suntv.in CIN.: L22110TN1985PLC012491 25th August, 2020 BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited Floor No . 25, P J Towers, Exchange Plaza Bandra - Reclamation Dalal Street, BandraKurla Complex, Bandra (E) Mumbai - 400 001 Mumbai - 400 051 Scrip Code: 532733, Scrip Id: SUNTV Symbol: SUNTV, Series: EQ Sir, Sub: Annual Report for the Financial Year 2019-20 Ref: Regulation 34 of SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 Pursuant to Regulation 34 of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulation, 2015, we are submitting herewith the Annual Report of the Company along with the Notice of ACM for the financial year 2019-20, which will be circulated to the Members through electronic mode. The 35th AGM will be held on Wednesday, September 16, 2020 at 10.00 a.m. 1ST through Video Conference / Other Audio-Visual Means (OAVM) in accordanc e with the relevant circulars issued by Ministry of Corporate Affairs and Securities and Exchange Board of India. This is for your information and records. Thanking you, For Sun TV Network Limited R. Ravi Company Secretary & Compliance Officer 35th Annual Report 2020 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Kalanithi Maran Executive Chairman R. Mahesh Kumar Managing Director Kavery Kalanithi Executive Director K. Vijaykumar Executive Director Kaviya Kalanithi Maran Executive Director S. Selvam Non-Executive Director M.K. Harinarayanan Independent Director J. Ravindran Independent Director Nicholas Martin Paul Independent Director R. -

A Research Upon Various Advancement in Privatisation and Broadcasting Regulation in Indian Satellite Television Channels

Journal of Advances and JournalScholarly of Advances and Researches in Scholarly Researches in AlliedAllied Education Education Vol.Vol. IX ,3, Issue Issue No. 6,XV III, April-201April5, -ISSN2012, 2230 -7540 ISSN 2230- 7540 REVIEW ARTICLE A RESEARCH UPON VARIOUS ADVANCEMENT AN IN PRIVATISATION AND BROADCASTING INTERNATIONALLY REGULATION IN INDIAN SATELLITE INDEXED PEER Study of Political Representations: REVIEWED & DiplomaticTELEVISION Missions CHANNELS of Early Indian to REFEREED JOURNAL Britain www.ignited.in Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. IX, Issue No. XVIII, April-2015, ISSN 2230-7540 A Research upon Various Advancement in Privatisation and Broadcasting Regulation in Indian Satellite Television Channels Dr. Keerty Goyal Freelance Journalist, Writer & Theatrist Abstract – In India till 1991 there was stand out television channel – Doordarshan, the public service broadcaster. With the opening up of the Indian economy in mid 1990s empowered the passage of private broadcasters in India? The quantity of television channels has multiplied complex. By 2005 India had more than 200 computerized channels. The quantity of television channels has developed from around 600 in 2010 to 800 in 2012.This incorporates more than 400 news and current undertakings channel. Mechanical changes have brought about extraordinary rivalry in news and general entertainment channels, as a consequence of which there is development in regional and specialty channels. The development of cable and satellite television and direct