The Palaeolithic Occupation of Europe As Revealed by Evidence from the Rivers: Data from IGCP 449

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blades), Side Scrapers

226 • PaleoAnthropology 2008 Figure 5. Tool types assigned to the Tres Ancien Paléolithique and the Lower Paleolithic. blades), side scrapers (single, double, and transverse), In Romanian archaeology, it is used as a synonym for the backed knives (naturally backed and with retouched back), Pebble Culture and is meant to designate Mode I indus- and notches/denticulates (Figure 6). tries, as can be inferred from the typology of the material (see Figure 5). Discussion A very difficult issue is learning what meaning under- tErMINoLOGY lies the term Lower Paleolithic itself. In order to clarify this This is a topic that is still very unclear for the Lower Pa- problem, one must look back a few decades, when there leolithic record of Romania. Inconsistencies regarding the was a belief that the cultures that postdate the Pebble Cul- terms are mentioned here. ture were the Abbevillian, Acheulian and Clactonian, all emerging from Pebble Culture industries. After the cul- tres Ancien Paléolithique (tAP) tural meaning of the Abbevillian and the Clactonian were This term refers, sensu Bonifay (Bonifay and Vandermeer- challenged, in Romanian archaeology the framing of this sch 1991), to industries that were prior to the emergence period became more cautious. There was no explicit shift of developed Acheulian bifaces and Levallois technology. defended in publications, but gradually the two terms fell Figure 6. Tool types assigned to the Premousterian. Lower Paleolithic of Romania • 227 out of use in defining distinct industries and became just supposed to be either Clactonian or Premousterian. Some- a typological and a technical description, respectively. At times, due to the particular morphology of the piece, ad- the same time, the existence of the Acheulian north of the ditional interpretations were made regarding the piece’s Danube was no longer claimed, but the term still was used various presumed functions, such as cutting, crushing and in classification of bifaces. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

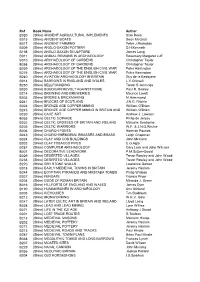

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

C H a P T E R VII Comparison of Stone Age Cultures the Cultural

158 CHAPTER VII Comparison of Stone Age Cultures The cultural horizons ami pleistocene sequences of the Upper Son Valley are compared with the other regions to know their positions in the development of Stone Age Cultures* However, ft must not be forgotten that the industries of various regions were more or less in fluenced by the local factors: the environment, geology f topography, vegetation, climate and animals; hence some vsriitions are bound to occur in them* The comparison is first made with industries within India and then with those outside India. i) Within India • Punjab Potwar The Potwar region, which lies between the Indus and Jhebm, including the Salt Range, was examined by Oe Terra and Pater son. The latter has recently published a revised 2 stuiy of the cultural horizons. 1. De Terra, H., and Paterson, T.T., 1939, Studies on the Ice Age in India and Associated Human Culture, pp.252-312 2. Paterson, T.T., and Drummond, H.J.H., 1962, Soan,the Palaeolithic of Pakistan. These scholars had successfully located six terraces (Including TD) in the Sohan Valley: "nowhere else in the Potwar is the leistocene history so well recorded as along the So&n Hiver and its tributaries.w The terraces TD and TI placed in the Second Glacial and Second Inter- glacial, respectively fall in the Middle Pleistocene, terraces ? and 3 originated in Third Glacial and Inter- glaual period. Th succeeding terrace viz., T4 has bean connected with the Fourth Glacial period. The last terrace - T5 - belongs to Post-glacLal and Holacene time. The oldest artifacts are located in the Boulder Con glomerate and are placed in the earliest Middle Pleisto cene or Lower Pleistocene. -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

The Earliest Evidence of Acheulian Occupation in Northwest

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The earliest evidence of Acheulian occupation in Northwest Europe and the rediscovery of the Moulin Received: 5 December 2017 Accepted: 19 August 2019 Quignon site, Somme valley, France Published: xx xx xxxx Pierre Antoine1, Marie-Hélène Moncel2, Pierre Voinchet2, Jean-Luc Locht1,3, Daniel Amselem2, David Hérisson 4, Arnaud Hurel2 & Jean-Jacques Bahain2 The dispersal of hominin groups with an Acheulian technology and associated bifacial tools into northern latitudes is central to the debate over the timing of the oldest human occupation of Europe. New evidence resulting from the rediscovery and the dating of the historic site of Moulin Quignon demonstrates that the frst Acheulian occupation north of 50°N occurred around 670–650 ka ago. The new archaeological assemblage was discovered in a sequence of fuvial sands and gravels overlying the chalk bedrock at a relative height of 40 m above the present-day maximal incision of the Somme River and dated by ESR on quartz to early MIS 16. More than 260 fint artefacts were recovered, including large fakes, cores and fve bifaces. This discovery pushes back the age of the oldest Acheulian occupation of north-western Europe by more than 100 ka and bridges the gap between the archaeological records of northern France and England. It also challenges hominin dispersal models in Europe showing that hominins using bifacial technology, such as Homo heidelbergensis, were probably able to overcome cold climate conditions as early as 670–650 ka ago and reasserts the importance of the Somme valley, where Prehistory was born at the end of the 19th century. -

The Distribution of Obsidian in the Eastern Mediterranean As Indication of Early Seafaring Practices in the Area a Thesis B

The Distribution Of Obsidian In The Eastern Mediterranean As Indication Of Early Seafaring Practices In The Area A Thesis By Niki Chartzoulaki Maritime Archaeology Programme University of Southern Denmark MASTER OF ARTS November 2013 1 Στον Γιώργο 2 Acknowledgments This paper represents the official completion of a circle, I hope successfully, definitely constructively. The writing of a Master Thesis turned out that there is not an easy task at all. Right from the beginning with the effort to find the appropriate topic for your thesis until the completion stage and the time of delivery, you got to manage with multiple issues regarding the integrated presentation of your topic while all the time and until the last minute you are constantly wondering if you handled correctly and whether you should have done this or not to do it the other. So, I hope this Master this to fulfill the requirements of the topic as best as possible. I am grateful to my Supervisor Professor, Thijs Maarleveld who directed me and advised me during the writing of this Master Thesis. His help, his support and his invaluable insight throughout the entire process were valuable parameters for the completion of this paper. I would like to thank my Professor from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Nikolaos Efstratiou who help me to find this topic and for his general help. Also the Professor of University of Crete, Katerina Kopaka, who she willingly provide me with all of her publications –and those that were not yet have been published- regarding her research in the island of Gavdos. -

Glaciation (Oakley, 1950). Variations in the Proposed Beginning Dates

EVOLUTION OF THE HUMAN HAND AMD THE GREAT HAND-AXE TRADITION Grover S. Krantz The hand-axe is both the earliest and the longest persisting of standar- dized stone tools. They present a continuous history of one tool type from the first to the third interglacial periods, a span.of at least 200,000 years and perhaps as many as half a million. Equally remarkable is their geographical range which covers all of Africa, western Europe and southern Asia--fully half of-the then habitable Old Vorld. Aside from differences in the local stone that was utilized, hand-axes from this whole area are constructed on the same plan and show no clear regional typology. Other tool types occur with hand-axes: utilized flakes are found at all levels, and in the later half of the sequence there-are cleavers, ovates, trimmed flakes and spherical stone balls. Throughout the sequence, however, the basic design of the hand-axe continues with its intended formnapparently unchanged. We thus have a continuous record of man's attempts to produce a single type of 'implement over mst of his tool making history. (See Figure 1.) Recent discoveries of fossil man have made it increasingly evident that biological evolution of the human body was also in progress coincident with the development of ancient stone tool types. 'While the exact time of appearance of Homo siens is still in some dispute (see Stewart, 1950 and Oakley., 1957), it is no nowseriously maintained that the earliest tool makers necessarily approximated the modern or even the neanderthal morphologies. -

Missouri State University 2019-20 Scholarship List

Missouri State University 2019-20 Scholarship List (Alphabetical) State and County City Oressa Abbegale Acs-Kinsey MO-Morgan Barnett Missouri State Promise Scholarship Gabriel Matthew Adams MO-Washington Mineral Point Inclusive Excellence Schlp 1 Madison Ann Agee MO-Polk Half Way Provost Scholarship Esperanza Aguilar MO-Saint Louis Saint Louis Provost Scholarship MSU - Wyman Scholarship Salema Marie Al-Baaj MO-Saint Louis City Saint Louis Inclusive Excellence Schlp 1 Jadan Joangelynn Almond MO-Daviess Jamesport Missouri State Promise Scholarship Rusul Hassanen Al-Shahrably MO-Saint Louis Saint Louis Missouri State Promise Scholarship Noel Isaiah Alvarado TX-Denton Lewisville Out-of-State Tuition Fee Waiver Amaya M Ambrosio MO-Clay Kearney Deans Scholarship Chase Andrew Anderson MO-Saint Louis Saint Louis A+ Recognition Scholarship Destiny Faith Apple MO-Taney Branson Missouri State Promise Scholarship Joel Anthony Arena MO-Saint Charles Saint Peters Board of Governors Scholarship Rachel A Arens MO-Callaway Fulton Board of Governors Scholarship Christian Anthony Armstrong MO-Christian Ozark Provost Scholarship Benjamin C Arnold MO-Platte Platte Woods Missouri State Promise Scholarship Dirk Henry Arnold MO-Dallas Elkland Missouri State Promise Scholarship Seth R Arvesen KS-Johnson Westwood State and County City Midwest Student Exchange Tuition Waiver Deans Scholarship Taylor Deneece Ashbrook MO-Livingston Chillicothe Inclusive Excellence Schlp 1 Mattie A Ashlock MO-Polk Bolivar Provost Scholarship Madison N Auer MO-Greene Springfield Board -

Supplementary Information For

Supplementary Information for An Abundance of Developmental Anomalies and Abnormalities in Pleistocene People Erik Trinkaus Department of Anthropology, Washington University, Saint Louis MO 63130 Corresponding author: Erik Trinkaus Email: [email protected] This PDF file includes: Supplementary text Figures S1 to S57 Table S1 References 1 to 421 for SI reference citations Introduction Although they have been considered to be an inconvenience for the morphological analysis of human paleontological remains, it has become appreciated that various pathological lesions and other abnormalities or rare variants in human fossil remains might provide insights into Pleistocene human biology and behavior (following similar trends in Holocene bioarcheology). In this context, even though there were earlier paleopathological assessments in monographic treatments of human remains (e.g., 1-3), it has become common to provide details on abnormalities in primary descriptions of human fossils (e.g., 4-12), as well as assessments of specific lesions on known and novel remains [see references in Wu et al. (13, 14) and below]. These works have been joined by doctoral dissertation assessments of patterns of Pleistocene human lesions (e.g., 15-18). The paleopathological attention has been primarily on the documentation and differential diagnosis of the abnormalities of individual fossil remains, leading to the growing paleopathological literature on Pleistocene specimens and their lesions. There have been some considerations of the overall patterns of the lesions, but those assessments have been concerned primarily with non-specific stress indicators and traumatic lesions (e.g., 13, 15, 19-21), with variable considerations of issues of survival 1 w ww.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1814989115 and especially the inferred social support of the afflicted (e.g., 22-27). -

Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: a Guide John J

Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide John J. Shea New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 408 pp. (hardback), $104.99. ISBN-13: 978-1-107-00698-0. Reviewed by DEBORAH I. OLSZEWSKI Department of Anthropology, Penn Museum, 3260 South Street, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] n reading the Preface and Introduction to Shea’s book Stone Age Prehistory,” and lists the origins of genus Homo Iwhere he discusses why he wrote this volume on Near in the Lower Paleolithic period, which is incorrect both Eastern stone tools, I had to smile because his experience as temporally and geographically (Homo ergaster appearing ca a graduate student was analogous to mine. Learning about 1.8 Mya in Africa, or Homo habilis ca 2.5 Mya in Africa, if one stone tools in this world region was not easy because no accepts this hominin as sufficiently derived as to belong to single typology had been developed, at least in the sense genus Homo). And the same is true in this table for several of a widely accepted set of terminology that could be ap- other major evolutionary events for which our earliest evi- plied to the Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic there, or even the dence is African rather than Levantine. Neolithic period. In retrospect, it is somewhat surprising For Chapter 2 (Lithics Basics), the reader is immedi- that in the several decades since no one, until this book by ately immersed in how stone fractures (using terminol- Shea, undertook producing a compendium of information ogy from mechanics), is abraded, and is knapped.