A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SITUATION of POLLING STATIONS UK Parliamentary East Hampshire Constituency

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS UK Parliamentary East Hampshire Constituency Date of Election: Thursday 8 June 2017 Hours of Poll: 7:00 am to 10:00 pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Ranges of electoral Ranges of electoral Station register numbers of Station register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote Number persons entitled to vote thereat thereat Alton Community Centre, Amery Street, St Mary`s R C Church Hall, 59 Normandy 1 AA-1 to AA-1848 2 AB-1 to AB-1961 Alton Street, Alton St Mary`s R C Church Hall, 59 Normandy Holybourne Village Hall, Church Lane, 3 AC-1 to AC-2083 4 AD-1 to AD-1558 Street, Alton Holybourne, Alton Alton Community Centre, Amery Street, 5 AE-1 to AE-2380 All Saints Parish Hall, Queens Road, Alton 6 AF-1 to AF-2418 Alton St John Ambulance Hq, Edgar Hall, Anstey Beech Village Hall, Wellhouse Road, 7 AG-1 to AG-1775/1 8 AH-1 to AH-484/4 Lane Beech Bentworth Jubilee Hall, Church Street, Bentley Memorial Hall, Hole Lane, Bentley 9 AI-1 to AI-892 10 AJ-1 to AJ-465 Bentworth Binsted Sports Pavillion, The Sports Jolly Farmer Public House (Skittle Alley), 11 AKA-1 to AKA-562 12 AKB-1 to AKB-893 Pavillion, The Street, Binsted Binsted Road, Blacknest Liphook Church Centre, Portsmouth Road, Liphook Church Centre, Portsmouth Road, 13 AL-1 to AL-1802 14 AL-1803 to AL-3605/5 Liphook Liphook Liphook Millennium Centre, 2 Ontario Way, Liphook Millennium Centre, 2 Ontario -

Chawton Park

What is being proposed? Enhancing Alton’s vitality and viability EHDC Retail Study Destination 2018 Turnover Benchmark Turnover Surplus/Deficit Bentworth Alton 63.47 80.83 -17.36 Chawton Park Whitehill & Bordon 36.89 27.34 +9.55 Large Development Site Alton Liphook 38.17 27.12 +11.05 Clanfield 3.41 1.57 +1.84 Beech Four Marks 4.99 6.78 -1.79 A31 Grayshott 5.89 5.94 -0.05 Chawton Horndean 25.99 31.25 -5.26 A31 Other East Hampshire 4.11 4.11 n/a Total 182.92 184.93 -2.01 Railway Line Convenience goods actual/benchmark turnover in 2018 (£ millions) Source: EHDC 2018 Site Location Plan Employment Allocation The above table is taken from the East Hampshire Retail and Main • 1200 homes including up to 480 affordable homes Town Centre Uses Study Final Report (October 2018): Table 4.4. It • Homes at an average density of 37 dwellings per hectare shows that despite convenience goods retail sales floorspace in • Local centre of up to 1 Ha with pub, shop, community the District collectively trading just under the expected average centre and employment space (-£2.01 million) in 2018, the performance in Alton is significantly below the benchmark turnover by some £17.36million. Key design themes of proposed development: Development at Chawton Park Farm would be sure to increase • High Quality Design • Sustainable Travel Choices footfall, and therefore provide great benefit to the retail economy of • Local Distinctiveness • Civic Pride the town. Proposed Aerial View • Good connections to Nature • Use of Technology • Enhancement of Historic Context • Long-term Management Chawton Park is located less than two miles from the centre • Green Infrastructure Summary of Alton, which is ranked as the No.1 settlement in the East Hampshire District Council Settlement Hierarchy Background How has Alton grown? • The land at Chawton Park is a suitable and appropriate site Paper, December 2018. -

Blades), Side Scrapers

226 • PaleoAnthropology 2008 Figure 5. Tool types assigned to the Tres Ancien Paléolithique and the Lower Paleolithic. blades), side scrapers (single, double, and transverse), In Romanian archaeology, it is used as a synonym for the backed knives (naturally backed and with retouched back), Pebble Culture and is meant to designate Mode I indus- and notches/denticulates (Figure 6). tries, as can be inferred from the typology of the material (see Figure 5). Discussion A very difficult issue is learning what meaning under- tErMINoLOGY lies the term Lower Paleolithic itself. In order to clarify this This is a topic that is still very unclear for the Lower Pa- problem, one must look back a few decades, when there leolithic record of Romania. Inconsistencies regarding the was a belief that the cultures that postdate the Pebble Cul- terms are mentioned here. ture were the Abbevillian, Acheulian and Clactonian, all emerging from Pebble Culture industries. After the cul- tres Ancien Paléolithique (tAP) tural meaning of the Abbevillian and the Clactonian were This term refers, sensu Bonifay (Bonifay and Vandermeer- challenged, in Romanian archaeology the framing of this sch 1991), to industries that were prior to the emergence period became more cautious. There was no explicit shift of developed Acheulian bifaces and Levallois technology. defended in publications, but gradually the two terms fell Figure 6. Tool types assigned to the Premousterian. Lower Paleolithic of Romania • 227 out of use in defining distinct industries and became just supposed to be either Clactonian or Premousterian. Some- a typological and a technical description, respectively. At times, due to the particular morphology of the piece, ad- the same time, the existence of the Acheulian north of the ditional interpretations were made regarding the piece’s Danube was no longer claimed, but the term still was used various presumed functions, such as cutting, crushing and in classification of bifaces. -

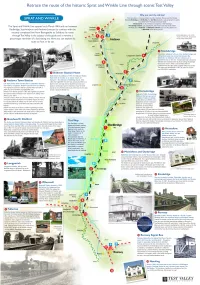

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

A Collection of Stylish New and Unique Converted Homes Set in the Grounds of an Historic Country Estate Near Alton in Hampshire

A collection of stylish new and unique converted homes set in the grounds of an historic country estate near Alton in Hampshire A breath of fresh air Froyle Park is so much more than a development of new luxury properties. Situated in the historic village of Upper Froyle, it is set in its own beautiful mature grounds, on the edge of the North Downs and in the picturesque Hampshire rolling countryside. This collection of stunning, new and restored homes have been carefully developed to enhance the character of both the retained buildings and the village setting. They offer access to a more refined and gentler pace of life, without compromising on the modern lifestyle and technological conveniences we have come to expect. These are not just homes, they are a way of life for those who would expect nothing less. TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 16 18 20 30 38 Upper Froyle and Travel In the presence Layout and The homes at Linden the local area connections of history architecture Froyle Park Homes 3 “ This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.” WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S RICHARD II 4 5 A location steeped in history Froyle consists of the two villages of Upper and Lower Froyle and is steeped in history dating back to 1086 where the entry in the Domesday Upper Froyle itself is Book states succinctly “Froyle – it was ever there”. The village is located known as ‘the village just outside Alton in Hampshire on the edge of The Downs above the of saints’ thanks to Pilgrims’ Way. the many statues of Today it is a bustling and thriving community. -

The Wyck Oast

THE WYCK OAST WYCK • HAMPSHIRE THE WYCK OAST WYCK • HAMPSHIRE Picturesque and versatile converted oast house nestled in the heart of the Hampshire countryside with superb gardens and grounds MAIN HOUSE Reception hall with double aspect staircase, dining room, orangery, drawing room, sitting room, study, x2 cloakrooms, x 2 kitchens, utility room, boiler room, mezzanine library. Master bedroom with dressing room & en suite bathroom, guest suite with balcony, dressing room and en suite bathroom, 4 further bedrooms with en suite bath/shower rooms. COTTAGE Open plan kitchen/sitting room, shower/cloakroom and bedroom. OUTSIDE 4 bay carport, 2 store rooms, landscaped gardens, terraces, tennis court and paddocks. In all about 5.1 acres. SAVILLS 39 Downing Street Farnham, Surrey GU9 7PH 01252 729000 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text DIRECTIONS Wyck is a picturesque rural hamlet located within the South Downs National Park. The location is peaceful and secluded, and benefits from From the centre of Farnham proceed along West Street and join the A31 having the neighbouring villages of East Worldham and Binsted which towards Alton. Stay on the A31 for 5 miles. Very shortly after passing the are accessed by the network of footpaths, bridleways and country lanes. Hen and Chicken PH on the other side of the A31, take the left turn off the In East Worldham there is a church and public house, whilst Binsted A31 sign posted for Binsted and Wyck and follow for a mile until reaching boasts a church, primary school and public house and the local village of a cross roads. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

C H a P T E R VII Comparison of Stone Age Cultures the Cultural

158 CHAPTER VII Comparison of Stone Age Cultures The cultural horizons ami pleistocene sequences of the Upper Son Valley are compared with the other regions to know their positions in the development of Stone Age Cultures* However, ft must not be forgotten that the industries of various regions were more or less in fluenced by the local factors: the environment, geology f topography, vegetation, climate and animals; hence some vsriitions are bound to occur in them* The comparison is first made with industries within India and then with those outside India. i) Within India • Punjab Potwar The Potwar region, which lies between the Indus and Jhebm, including the Salt Range, was examined by Oe Terra and Pater son. The latter has recently published a revised 2 stuiy of the cultural horizons. 1. De Terra, H., and Paterson, T.T., 1939, Studies on the Ice Age in India and Associated Human Culture, pp.252-312 2. Paterson, T.T., and Drummond, H.J.H., 1962, Soan,the Palaeolithic of Pakistan. These scholars had successfully located six terraces (Including TD) in the Sohan Valley: "nowhere else in the Potwar is the leistocene history so well recorded as along the So&n Hiver and its tributaries.w The terraces TD and TI placed in the Second Glacial and Second Inter- glacial, respectively fall in the Middle Pleistocene, terraces ? and 3 originated in Third Glacial and Inter- glaual period. Th succeeding terrace viz., T4 has bean connected with the Fourth Glacial period. The last terrace - T5 - belongs to Post-glacLal and Holacene time. The oldest artifacts are located in the Boulder Con glomerate and are placed in the earliest Middle Pleisto cene or Lower Pleistocene. -

MARCH 2018 No: 441

FROYLE VILLAGE MAGAZINE MARCH 2018 No: 441 http://www.froyle.com/magazine/magazine.htm Advertising in the Froyle Village Magazine The rates are as follows: For Froyle businesses £3.50 +VAT/month for advertisements of up to half a page. For non-Froyle businesses: £5 +VAT/month for up to half a page. For both residents and non residents: £10 +VAT/month for a full page and £5 + VAT for a third of a page in the inside covers. All advertising must be requested and paid for through the Parish Clerk at [email protected] and co pied to [email protected] PARISH NEWS & VIEWS Parish Clerk - Philippa Cullen Stephenson Crabtree Gate, Well Lane, Lower Froyle Tel: 01420 520102 Email: [email protected] Web: www.froyleparishcouncil.org.uk FROYLE PARISH COUNCIL The Froyle Parish Council did not meet in February. The next meeting will be on Tuesday 13th March at 7.45pm in the Village Hall. MARCH EVENTS Lent lunches 2018 Running throughout Lent, these lunches are a simple soup, bread and cheese affair, in aid of a charity chosen by the host/hostess. They take place between 12.30 and 2.00 pm, and all donations from those attending will be gratefully received. If anyone needs a lift, would like to offer a lift, or has any other queries, please call me on 23697. The venues for the Lent lunches in March are as follows: Thursday March 8th (note change of day) at The Old Malthouse, in aid of Canine Partners (Gill Bradley 520484) March 14th at Beech Cottage, in aid of 'Thrive' (Caroline Findlay 22019) March 21st at Copse Hill Farm, in aid of Canine Partners (Jane Macnabb 23195). -

Site CD0008 - Chesham Car and Van Sales Bellingdon Road(Chesham Parish), Chiltern District

Site CD0008 - Chesham Car and Van Sales Bellingdon Road(Chesham Parish), Chiltern District 3 2 0 7 1 2 2 F 5 F 7 0 ¯ 4 5 0 2 3 5 3 1 Def 2 Esprit 9 5 F 5 F 1 F 1 F 3 1 RO F AD Works W 108.2m F W 5 El F F 1 23 7 C 4 F 43 C W 1 41 39 107.0m Gardens 29 6 32 TCB B 6 E 3 L L IN 1 G 5 D 2 O 12 N 3 R O A 1 D 24 5 8 5 8 5 1 9 6 2 1 8 7 23 9 1 2 35 0 9 to H 2 2 5 9 A 2 2 2 R 5 to R IE 2 4 S 8 7 8 C 1 L 1 3 O 1 S 19 E 6 106.1m 7 Not to Scale 1 to 9 Legend Chiltern District Brownfield Land Register Part 1 Site Site CD0031 - Wicks Garage Rignall Road(Great Missenden Parish), Chiltern District ¯ Orchard Corner 6 7 1 3 e g a r a L G C D N A L D 2 A 1 E H 133.4m The Old Orchard 5 133.6m 3 1 El Su b Sta 34 5 3 32 Cherry Tree Cottage 1 t Not to Scale 11 o 18 Legend Chiltern District Brownfield Land Register Part 1 Site Green Belt Site CD0109 - Coach Depot and Adjacent Land Lycrome Road, Lye Green (Chesham Parish), Chiltern District El P ¯ Def Mattesdon T o b B H a o r u n s s e i t Lye Green e 2 1 161.5m Bus Depot D A O R 7 El 6 4 th 3 a 2 Cat P Whitehouse GP Willow Bank Delmar 161.8m GP E T L e e e g l g a a t a t d t t o Note: Ann y future development proposals should consider that the site is o C e l C e within thG e Green Belt. -

Sandwich Bay and Hacklinge Marshes Districts

COUNTY: KENT SITE NAME: SANDWICH BAY AND HACKLINGE MARSHES DISTRICTS: THANET/DOVER Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) notified under Section 28 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 Local Planning Authority: THANET DISTRICT COUNCIL/DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL National Grid Reference: TR 353585 Area: 1756.5 (ha.) 4338.6 (ac.) Ordnance Survey Sheet 1:50,000: 179 1:10,000: TR 35 NE, NW, SE, SW; TR 36 SW, SE Date Notified (Under 1949 Act): 1951 Date of Last Revision: 1981 Date Notified (Under 1981 Act): 1984 (part) Date of Last Revision: 1994 1985 (part) 1990 Other Information: Parts of the site are listed in ÔA Nature Conservation ReviewÕ and in ÔA Geological Conservation ReviewÕ2. The nature reserve at Sandwich Bay is owned jointly by the Kent Trust for Nature Conservation, National Trust and Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. The site has been extended to include a Kent Trust designated Site of Nature Conservation Interest known as Richborough Pasture and there are several other small amendments. Reasons for Notification: This site contains the most important sand dune system and sandy coastal grassland in South East England and also includes a wide range of other habitats such as mudflats, saltmarsh, chalk cliffs, freshwater grazing marsh, scrub and woodland. Associated with the various constituent habitats of the site are outstanding assemblages of both terrestrial and marine plants with over 30 nationally rare and nationally scarce species, having been recorded. Invertebrates are also of interest with recent records including 19 nationally rare3, and 149 nationally scarce4 species. These areas provide an important landfall for migrating birds and also support large wintering populations of waders, some of which regularly reach levels of national importance5.