From Semir Zeki to John Onians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Boundary Extension: Anticipatory Scene Representation Across Development and Disorder

Received: 23 July 2016 | Revised: 14 January 2017 | Accepted: 19 January 2017 DOI: 10.1002/hipo.22728 RESEARCH ARTICLE Testing the “Boundaries” of boundary extension: Anticipatory scene representation across development and disorder G. Spano1,2 | H. Intraub3 | J. O. Edgin1,2,4 1Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 Abstract 2Cognitive Science Program, University of Recent studies have suggested that Boundary Extension (BE), a scene construction error, may be Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 linked to the function of the hippocampus. In this study, we tested BE in two groups with varia- 3Department of Psychological and Brain tions in hippocampal development and disorder: a typically developing sample ranging from Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, preschool to adolescence and individuals with Down syndrome. We assessed BE across three dif- Delaware 19716 ferent test modalities: drawing, visual recognition, and a 3D scene boundary reconstruction task. 4Sonoran University Center for Excellence in Despite confirmed fluctuations in memory function measured through a neuropsychological Developmental Disabilities, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 assessment, the results showed consistent BE in all groups across test modalities, confirming the Correspondence near universal nature of BE. These results indicate that BE is an essential function driven by a com- Goffredina Spano, Wellcome Trust Centre plex set of processes, that occur even in the face of delayed memory development and for Neuroimaging, Institute of Neurology, hippocampal dysfunction in special populations. University College London, 12 Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, UK. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS Funding information down syndrome, memory development, hippocampus, prediction error, top-down influences LuMind Research Down Syndrome Foundation; Research Down Syndrome and the Jerome Lejeune Foundation; Molly Lawson Graduate Fellow in Down Syndrome Research (GS). -

Mind-Wandering in People with Hippocampal Damage

This Accepted Manuscript has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. Research Articles: Behavioral/Cognitive Mind-wandering in people with hippocampal damage Cornelia McCormick1, Clive R. Rosenthal2, Thomas D. Miller2 and Eleanor A. Maguire1 1Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, WC1N 3AR, UK 2Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DU, UK DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1812-17.2018 Received: 29 June 2017 Revised: 21 January 2018 Accepted: 24 January 2018 Published: 12 February 2018 Author contributions: C.M., C.R.R., T.D.M., and E.A.M. designed research; C.M. performed research; C.M., C.R.R., T.D.M., and E.A.M. analyzed data; C.M., C.R.R., T.D.M., and E.A.M. wrote the paper. Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests. We thank all the participants, particularly the patients and their relatives, for the time and effort they contributed to this study. We also thank the consultant neurologists: Drs. M.J. Johnson, S.R. Irani, S. Jacobs and P. Maddison. We are grateful to Martina F. Callaghan for help with MRI sequence design, Trevor Chong for second scoring the Autobiographical Interview, Alice Liefgreen for second scoring the mind-wandering thoughts, and Elaine Williams for advice on hippocampal segmentation. E.A.M. and C.M. are supported by a Wellcome Principal Research Fellowship to E.A.M. (101759/Z/13/Z) and the Centre by a Centre Award from Wellcome (203147/Z/16/Z). -

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Decoding Representations of Scenes in the Medial Temporal Lobes

HIPPOCAMPUS 22:1143–1153 (2012) Decoding Representations of Scenes in the Medial Temporal Lobes Heidi M. Bonnici,1 Dharshan Kumaran,2,3 Martin J. Chadwick,1 Nikolaus Weiskopf,1 Demis Hassabis,4 and Eleanor A. Maguire1* ABSTRACT: Recent theoretical perspectives have suggested that the (Eichenbaum, 2004; Johnson et al., 2007: Kumaran function of the human hippocampus, like its rodent counterpart, may be et al., 2009) and even visual perception (Lee et al., best characterized in terms of its information processing capacities. In this study, we use a combination of high-resolution functional magnetic 2005; Graham et al., 2006, 2010). Current perspec- resonance imaging, multivariate pattern analysis, and a simple decision tives, therefore, have emphasized that the function of making task, to test specific hypotheses concerning the role of the the hippocampus, and indeed surrounding areas within medial temporal lobe (MTL) in scene processing. We observed that the medial temporal lobe (MTL), may be best charac- while information that enabled two highly similar scenes to be distin- guished was widely distributed throughout the MTL, more distinct scene terized by understanding the nature of the information representations were present in the hippocampus, consistent with its processing they perform. role in performing pattern separation. As well as viewing the two similar The application of multivariate pattern analysis scenes, during scanning participants also viewed morphed scenes that (MVPA) techniques applied to functional magnetic spanned a continuum between the original two scenes. We found that patterns of hippocampal activity during morph trials, even when resonance imaging (fMRI) data (Haynes and Rees, perceptual inputs were held entirely constant (i.e., in 50% morph 2006; Norman et al., 2006) offers the possibility of trials), showed a robust relationship with participants’ choices in the characterizing the types of neural representations and decision task. -

From Squirrels to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): the Modulation of the Hippocampus

The Science Journal of the Lander College of Arts and Sciences Volume 10 Number 1 Tenth Anniversary Edition: Fall 2016 - 2016 From Squirrels to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): The Modulation of the Hippocampus Rachel Ariella Bartfeld Touro College Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/sjlcas Part of the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Commons, and the Nervous System Commons Recommended Citation Bartfeld, R. A. (2016). From Squirrels to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): The Modulation of the Hippocampus. The Science Journal of the Lander College of Arts and Sciences, 10(1). Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/sjlcas/vol10/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Science Journal of the Lander College of Arts and Sciences by an authorized editor of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Squirrels to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): The Modulation of the Hippocampus Rachel Ariella Bartfeld Rachel Ariella Bartfeld graduated with a BS in Biology, Minor in Psychology in September 2016 and is accepted to Quinnipiac University, Frank H. Netter School of Medicine Abstract The legitimacy of psychotherapy can often be thrown into doubt as its mechanisms of action are generally considered hazy and unquantifiable. One way to support the effectiveness of therapy would be to demonstrate the physical effects that this treatment option can have on the brain, just like psychotropic medications that physically alter the brain’s construction leaving no doubt as to the potency of their effects. -

Smutty Alchemy

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2021-01-18 Smutty Alchemy Smith, Mallory E. Land Smith, M. E. L. (2021). Smutty Alchemy (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113019 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Smutty Alchemy by Mallory E. Land Smith A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2021 © Mallory E. Land Smith 2021 MELS ii Abstract Sina Queyras, in the essay “Lyric Conceptualism: A Manifesto in Progress,” describes the Lyric Conceptualist as a poet capable of recognizing the effects of disparate movements and employing a variety of lyric, conceptual, and language poetry techniques to continue to innovate in poetry without dismissing the work of other schools of poetic thought. Queyras sees the lyric conceptualist as an artistic curator who collects, modifies, selects, synthesizes, and adapts, to create verse that is both conceptual and accessible, using relevant materials and techniques from the past and present. This dissertation responds to Queyras’s idea with a collection of original poems in the lyric conceptualist mode, supported by a critical exegesis of that work. -

Watching Movies Unfold – a Frame-By-Frame Analysis of the Associated Neural Dynamics

Research Article: New Research | Cognition and Behavior Watching movies unfold – a frame-by-frame analysis of the associated neural dynamics https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0099-21.2021 Cite as: eNeuro 2021; 10.1523/ENEURO.0099-21.2021 Received: 14 March 2021 Revised: 21 May 2021 Accepted: 2 June 2021 This Early Release article has been peer-reviewed and accepted, but has not been through the composition and copyediting processes. The final version may differ slightly in style or formatting and will contain links to any extended data. Alerts: Sign up at www.eneuro.org/alerts to receive customized email alerts when the fully formatted version of this article is published. Copyright © 2021 Monk et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed. 1 2 3 Watching movies unfold – a frame-by-frame analysis of the associated neural 4 dynamics 5 6 7 Abbreviated title: Event processing and the hippocampus 8 9 10 Authors: Anna M. Monk, Daniel N. Barry, Vladimir Litvak, Gareth R. Barnes, Eleanor A. Maguire 11 12 13 Affiliation: Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, UCL Queen Square Institute of 14 Neurology, University College London, 12 Queen Square, London WC1N 3AR, UK 15 16 17 Author contributions: A.M.M. and E.A.M. designed the research; A.M.M. Performed the 18 research; All authors Analyzed the data; A.M.M. and E.A.M. wrote the paper 19 20 21 Correspondence should be addressed to Eleanor Maguire: [email protected] 22 23 24 Number of Figures: 3 25 Number of Tables: 0 26 Number of Multimedia: 0 27 Number of words for Abstract: 245 28 Number of words for significance statement: 107 29 Number of words for Introduction: 736 30 Number of words for Discussion: 2127 31 32 33 Acknowledgements: Thanks to Daniel Bates, David Bradbury and Eric Featherstone for technical 34 support, and Zita Patai for analysis advice. -

BIPN140 Lecture 14: Learning & Memory

Cellular Neurobiology BIPN140 Second midterm is next Tuesday!! Covers lectures 7-12 (Synaptic transmission, NT & receptors, intracellular signaling & synaptic plasticity). Review session is on Monday (Nov 14th) before midterm 6:00-8:00 PM at 3500 Pacific Hall (Code: 286856). Please come with questions. Peixin’s section tomorrow (2:00-3:00) is cancelled due to Veteran's Day. Additional office hour will be held by Milad & Antonia tomorrow at Pacific Hall 3502, 12:00-2:00 PM. PS 6 Q&A is now posted on the website 2015 Problem sets #4~ #6 and 2nd midterm are also posted! Chih-Ying’s Office Hour: Monday, 1:00-2:00 PM, Bonner Hall 4146 BIPN140 Lecture 14: Learning & Memory 1. Categories of Memory 2. Anterograde v.s. Retrograde Amnesia 3. Brain regions critical for memory Su (FA16) The Major Qualitative Categories of Human Memory (Fig. 31.1) episodic semantic classical conditioning Priming: a change in the processing of a stimulus due to a previous encounter with the same or similar stimulus Temporal Categories of Memory: Phases of Memory (Fig. 31.2) Patient H.M. & Brenda Milner (Box 31c) (Brenda Milner, 1918-) (H.M. 1926-2008) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/corkin-hm-memory.html H.M.: Learning without Realizing it (Kandel et al., Principles of Neural Science, 5th Edition) Brain Areas Associated with Declarative Memory Disorders (Fig. 31.9a) Amygdala: required for fear-based memory Spatial Learning & Memory in Rodents Depends on the Hippocampus (Fig. 31.10) The Case of London Taxi Drivers (Fig. 31.12A) Spatial hypothesis of hippocampal function: the “spatial maps” stored in the hippocampus enable flexible navigation by encoding several routes to the same direction. -

Plasticity in the Human Hippocampus

Plasticity in the Human Hippocampus Katherine Woollett Submitted for PhD in Cognitive Neuroscience October 2010 University College London Supervisor: Eleanor A. Maguire Declaration: I, Katherine Woollett, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Date: Abstract If we are to approach rehabilitation of memory-impaired patients in a systematic and efficacious way, then it is vital to know if the human memory system has the propensity for plasticity in adulthood, the limiting factors on such plasticity, and the timescales of any plastic change. This thesis was motivated by an attempt to develop a body of knowledge in relation to these questions. There is wide agreement that the hippocampus plays a key role in navigation and memory across species. Evidence from animal studies suggests that spatial memory- related hippocampal volume changes and experience-related hippocampal neurogenesis takes place throughout the lifespan. Previous studies in humans indicated that expert navigators, licensed London taxi drivers, have different patterns of hippocampal grey matter volume relative to control participants. In addition, preliminary evidence also suggested there may be functional consequences associated with this grey matter pattern. Using licensed London taxi drivers as a model for learning and memory, the work undertaken centered on four key issues: (1) In a set of studies, I characterised the neuropsychological profile of licensed London taxi drivers in detail, which included devising a number of new table-top associational memory tests. This enabled me to assess the functional consequences of their expertise and hippocampal grey matter pattern in greater depth than previous studies. -

IB Psychology Course Psychologyib Introduction Tothe Introduction

Introduction to the IB Psychology Course IB Psychology IB Welcome to the IB Psychology course. I thought we would start with a brief overview of how the course is organised and the key pieces of information you need to know, before we launch into some research tasks linked to the main approaches in Psychology. There are three key approaches: Biological, Cognitive and Sociocultural. You will need to have an in depth, detailed knowledge of their assumptions and preferred methods of research. In addition to understanding the importance and application of ethics. The content that you learn will fall under one of these three approaches. You will also have to research a specific area, conduct your own scientific experiment and formally write up your research study. This will form 20% (22 marks) of your overview grade. So let’s have a look at how you will be assessed at the end of the two years. IB Psychology IB Course Description & Aims The IB Diploma Programme higher level psychology course aims to develop an awareness of how research findings can be applied to better understand human behaviour and how ethical practices are upheld in psychological inquiry. You will learn to understand the biological, cognitive and sociocultural influences on human behaviour and explore alternative explanations of behaviour. You will also understand and use diverse methods of psychological inquiry. In addition, the course is designed to: • encourage the systematic and critical study of human experience and behaviour; physical, economic and social environments; -

Introducing Neuropsychology, Second Edition

Introducing Neuropsychology Introducing Neuropsychology, second edition investi- edition, key topics are dealt with in separate focus gates the functions of the brain and explores the boxes, and “interim comment” sections allow the relationships between brain systems and human reader a chance to “take stock” at regular intervals. behaviour. The material is presented in a jargon-free, The book assumes no particular expertise on easy to understand manner and aims to guide the reader’s part in either psychology or brain students new to the field through current areas of physiology. Thus, it will be of great interest not only research. to those studying neuropsychology and cognitive Following a brief history of the discipline and a neuroscience, but also to medical and nursing description of methods in neuropsychology, the students, and indeed anyone who is interested in remaining chapters review traditional and recent learning about recent progress in understanding research findings. Both cognitive and clinical aspects brain–behaviour relationships. of neuropsychology are addressed to illustrate the advances scientists are making (on many fronts) in John Stirling has worked at Manchester Polytechnic/ their quest to understand brain–behaviour relation- MMU for over 30 years, teaching Bio- and Neuro- ships in both normal and disturbed functioning. The psychology, Psychopathology and Experimental rapid developments in neuropsychology and cogni- Design and Statistics. He has published over 30 tive neuroscience resulting from traditional research scientific journal articles, and three books. methods as well as new brain-imaging techniques are presented in a clear and straightforward way. Each Rebecca Elliott has worked at the University of chapter has been fully revised and updated and new Manchester for 8 years, using brain-imaging tech- brain-imaging data are incorporated throughout, niques to study emotion and cognition in psychiatric especially in the later chapters on Emotion and disorders. -

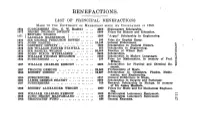

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND .