VIOLENCE in QUEBEC J.1Cgil1 University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quebec's New Politics of Redistribution Meets Austerity1

4 Quebec’s New Politics of Redistribution Meets Austerity1 Alain Noël In the late 1990s, wrote Keith Banting and John Myles in their Inequality and the Fading of Redistributive Politics, Quebec represented “the road not taken by the rest of Canada” (2013, 18). While the redistributive state was fading across Canada, the province bucked the trend and im- proved its social programs, preventing the rise of inequality observed elsewhere. The key, argued Banting and Myles, was politics. With strong trade unions, well-organized social movements, and a left-of-centre partisan consensus, Quebec redefined its social programs through a politics of compromise that conciliated efforts to balance the budget with social policy improvements. In this respect, Quebec’s new politics of redistribution in the late 1990s and early 2000s seemed more akin to the coalition-building dynamics of continental European countries than to the more divisive politics of liberal, English-speaking nations (Banting and Myles 2013, 17). Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, in the 1960s and 1970s, was a modern- ization process, whereby the province sought to catch up with the rest of Canada and meet North American standards. The Quebec govern- ment insisted on defining autonomously its own social programs, but overall its policies converged with those pursued elsewhere in Cana- 1. I am grateful to the editors and to Denis Saint-Martin for comments and suggestions. Federalism and the Welfare State in a Multicultural World, edited by Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant, Richard Johnston, Will Kym- licka, and John Myles. Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, Queen’s Policy Studies Series. -

Proquest Dissertations

COMMEMORATING QUEBEC: NATION, RACE, AND MEMORY Darryl RJ. Leroux M.?., OISE/University of Toronto, 2005 B.A. (Hon), Trent University, 2003 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED G? PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of Sociology and Anthropology CARLETON UNIVERSITY Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario June 2010 D 2010, Darryl Leroux Library and Archives Bibliothèque et ?F? Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70528-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70528-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Carleton University, 1992 C.E.P., Institut D’Etudes Politiques De Paris, 1993

Diversity and Uniformity in Conceptions of Canadian Citizenship by Byron Bennett Magnusson Homer B.A. (Honours), Carleton University, 1992 C.E.P., Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED iN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDifiS Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1994 Byron Bennett Magnusson Homer, 1994 _________ ____________________________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of %Eco..\ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ii Abstract This thesis uses philosophical and conceptual analysis to examine communitarian critiques of homogenous liberal conceptions of citizenship and the contemporary recognition pressures in the Canadian polity. It attempts to make some observations on the degree of difference that the Canadian society could support without destroying the sentimental bond of citizenship that develops when citizens feel they belong to the same moral and political community. The assumption made in our introduction is that diversity or differentiation becomes too exaggerated when citizens no longer feel like they are similar and can reach agreement on common objectives. -

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

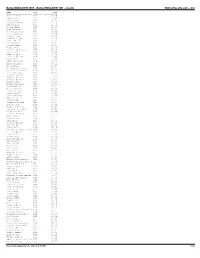

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

1 Separatism in Quebec

1 Separatism in Quebec: Off the Agenda but Not Off the Minds of Francophones An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Politics in Partial Fulfillment of the Honors Program By Sarah Weber 5/6/15 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 3 Chapter 2. 4 Chapter 3. 17 Chapter 4. 36 Chapter 5. 41 Chapter 6. 50 Chapter 7. Conclusion 65 3 Chapter 1: Introduction-The Future of Quebec The Quebec separatist movement has been debated for decades and yet no one can seem to come to a conclusion regarding what the future of the province holds for the Quebecers. This thesis aims to look at the reasons for the Quebec separatist movement occurring in the past as well as its steady level of support. Ultimately, there is a split within the recent literature in Quebec, regarding those who believe that independence is off the political agenda and those who think it is back on the agenda. This thesis looks at public opinion polls, and electoral returns, to find that the independence movement is ultimately off the political agenda as of the April 2014 election, but continues to be supported in Quebec public opinion. I will first be analyzing the history of Quebec as well as the theories other social scientists have put forward regarding separatist and nationalist movements in general. Next I will be analyzing the history of Quebec in order to understand why the Quebec separatist movement came about. I will then look at election data from 1995-2012 in order to identify the level of electoral support for separatism as indicated by the vote for the Parti Quebecois (PQ). -

Quebec Women and Legislative Representation

Quebec Women and Legislative Representation Manon Tremblay Quebec Women and Legislative Representation TRANSLATED BY KÄTHE ROTH © UBC Press 2010 Originally published as Québécoises et représentation parlementaire © Les Presses de l’Université Laval 2005. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada on FSC-certified ancient-forest-free paper (100% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Tremblay, Manon, 1964- Quebec women and legislative representation / written by Manon Tremblay ; translated by Käthe Roth. Originally published in French under title: Québécoises et représentation parlementaire. ISBN 978-0-7748-1768-4 1. Women legislators – Québec (Province). 2. Women in politics – Québec (Province). 3. Representative government and representation – Canada. 4. Legislative bodies – Canada. I. Roth, Käthe II. Title. HQ1236.5.C2T74513 2010 320.082’09714 C2009-903402-6 UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), and of the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. -

The Meaning of Canadian Federalism in Québec: Critical Reflections

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert The Meaning of Canadian federalisM in QuébeC: CriTiCal refleCTions guy laforest Professor of Political Science at the Laval University, Québec SUMMARY: 1. Introdution. – 2. Interpretive context. – 3. Contemporary trends and scholarship, critical reflections. – Conclusion. – Bibliography. – Abstract-Resum-Re- sumen. 1. Introduction As a teacher, in my instructions to students as they prepare their term papers, I often remind them that they should never abdicate their judgment to the authority of one single source. In the worst of circum- stances, it is much better to articulate one’s own ideas and convictions than to surrender to one single book or article. In the same spirit, I would urge readers not to rely solely on my pronouncements about the meaning of federalism in Québec. In truth, the title of this essay should include a question mark, and its content will illustrate, I hope, the richness and diversity of current Québec thinking on the subject. There are many ways as well to approach the topic at hand. The path I shall choose will reflect my academic identity: I am a political theorist and an intellectual historian, keenly interested about the relationship between philosophy and constitutional law in Canada, hidden in a political science department. As a reader of Gadamer and a former student of Charles Taylor, I shall start with some interpretive or herme- neutical precautions. Beyond the undeniable relevance of current re- flections about the theory of federalism in its most general aspects, the real question of this essay deals with the contemporary meaning of Canadian federalism in Québec. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

The Roots of French Canadian Nationalism and the Quebec Separatist Movement

Copyright 2013, The Concord Review, Inc., all rights reserved THE ROOTS OF FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND THE QUEBEC SEPARATIST MOVEMENT Iris Robbins-Larrivee Abstract Since Canada’s colonial era, relations between its Fran- cophones and its Anglophones have often been fraught with high tension. This tension has for the most part arisen from French discontent with what some deem a history of religious, social, and economic subjugation by the English Canadian majority. At the time of Confederation (1867), the French and the English were of almost-equal population; however, due to English dominance within the political and economic spheres, many settlers were as- similated into the English culture. Over time, the Francophones became isolated in the province of Quebec, creating a densely French mass in the midst of a burgeoning English society—this led to a Francophone passion for a distinct identity and unrelent- ing resistance to English assimilation. The path to separatism was a direct and intuitive one; it allowed French Canadians to assert their cultural identities and divergences from the ways of the Eng- lish majority. A deeper split between French and English values was visible before the country’s industrialization: agriculture, Ca- Iris Robbins-Larrivee is a Senior at the King George Secondary School in Vancouver, British Columbia, where she wrote this as an independent study for Mr. Bruce Russell in the 2012/2013 academic year. 2 Iris Robbins-Larrivee tholicism, and larger families were marked differences in French communities, which emphasized tradition and antimaterialism. These values were at odds with the more individualist, capitalist leanings of English Canada. -

Canadian Chronology 1079

Canadian chronology 1079 current rates of consumption. Total production of higher, July 10, The Economic Council of Canada the economy dropped by 1,4% during the first three recommended that Canada vigorously pursue a months of 1975, the worst quarterly decline In the free trade arrangement covering all countries, July GNP since It fell 1,5% in the first quarter of 1961, 16, Rapidly dwindling natural gas supplies would Statistics Canada reported, June 16, Transport require the government to reduce exports to Minister Jean Marchand unveiled a new federal United States markets and to restrain domestic transportation policy with proposed expenditures consumption until new frontier supplies were up to $45 billion over 15 years; the aim of making available. Energy Minister Donald Macdonald said advanced transport systems pay their own way in the House of Commons, July 17, Manitoba's would mean rapidly rising travel and shipping costs minimum wage for workers over 18 would rise to to consumers, June 17, A Paris court ordered the $2,60 an hour from $2,30 effective Oct, 1, Labour French government to compensate Canadian Minister A,R, Paulley announced. Prime Minister David McTaggart for the deliberate ramming of his Trudeau sent congratulations to the leaders of the protest ship Greenpeace III by a French naval vessel United States and the Soviet Union on the historic in the South Pacific In June 1972, June 18, The linkup of the Apollo and Soyuz spaceships, July 18, Anglican Church of Canada accepted the ordination Government screening of new -

A Comparative Analysis of Party Based Foreign Policy Co

Political Parties and Party Systems in World Politics: A Comparative Analysis of Party Based Foreign Policy Contestation and Change AngelosStylianos Chryssogelos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, December, 2012 European University Institute Department of Political and Social Sciences Political Parties and Party Systems in World Politics: A Comparative Analysis of PartyBased Foreign Policy Contestation and Change AngelosStylianos Chryssogelos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Dr. Friedrich Kratochwil, EUI (Supervisor) Professor Dr. Luciano Bardi, University of Pisa Professor Dr. Sven Steinmo, EUI Professor Dr. Bertjan Verbeek, Radboud University Nijmegen © AngelosStylianos Chryssogelos, 2012 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author ABSTRACT The argument of this dissertation is that instances of foreign policy change can be best understood as interactions between ongoing dynamics of important aspects of domestic party systems and changes in a state’s normative and material international environment. I identify three types of dynamics of party systems: different patterns of coalition and opposition, different patterns of expression of social cleavages through parties, and redefinitions of the meaning attached to the main axis of competition. These dynamics provide partisan actors with the ideational resources to make sense of changes in the international system, contribute to the creation of new (domestic and foreign) policy preferences and bring about political incentives for the promotion of new foreign policies. -

Ministerial Error and the Political Process: Is There a Duty to Resign? Stuart James Whitley

Ministerial Error and the Political Process: Is there a Duty to Resign? Stuart James Whitley, QC* In practice, it is seldom very hard to do one’s duty when one knows what it is. But it is sometimes exceedingly difficult to find this out. - Samuel Butler (1912) “First Principles” Note Books The honourable leader is engaged continuously in the searching of his (sic) duty. Because he is practicing the most powerful and most dangerous of the arts affecting, however humbly, the quality of life and the human search for meaning, he ought to have – if honourable, he has to have – an obsession with duty. What are his responsibilities? -Christopher Hodgkinson (1983) The Philosophy of Leadership Abstract: This article examines the nature of the duty to resign for error in the ministerial function. It examines the question of resignation as a democratic safeguard and a reflection of a sense of honour among those who govern. It concludes that there is a duty to resign for misleading Parliament, for serious personal misbehaviour, for a breach of collective responsibility, for serious mismanagement of the department for which they are responsible, and for violations of the rule of law. The obligation is owed generally to Parliament, and specifically to the Prime Minister, who has the constitutional authority in any event to dismiss a minister. The nature of the obligation is a constitutional convention, which can only be enforced by political action, though a breach of the rule of law is reviewable in the courts and may effectively disable a minister. There appears to be uneven historical support for the notion that ministerial responsibility includes the duty to resign for the errors of officials except in very narrow circumstances.