Grammaticalization in Germanic Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grammaticalization of Demonstratives: a Comparative Analysis

Nicholas Catasso 7 Journal of Universal Language 12-1 March 2011, 7-46 The Grammaticalization of Demonstratives: A Comparative Analysis Nicholas Catasso Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia * Abstract An article, irrespective of its distribution across natural languages, dialects and varieties, is a member of the class of determiners which particularizes a noun according to language-specific principles of grammatical and semantic structuring. Definite articles in Indo- European languages – in those grammatical systems where they are present – are derived from ancient demonstratives through a grammaticalization process: given that demonstratives are deictic expressions (i.e. they depend on a frame of reference which is external to that of the speaker and of the interlocutor) with the role of selecting a referent or a set of referents, it is easy to understand what the role of “universal quantifier” of the, which is in English the prototypical – but questionable – example of definiteness, is due to. Demonstratives are frequently reanalyzed across languages as grammatical markers (very often as definite articles, but also as copulas, relative and third person pronouns, sentence connectives, Nicholas Catasso Dipartimento di Scienze del Linguaggio - Dorsoduro 3462 - VENEZIA 30123 (VE) Phone 0039-3463157243; Email: [email protected] Received Oct. 2010; Reviewed Dec. 2010; Revised version received Jan. 2011. 8 The Grammaticalization of Demonstratives: A Comparative Analysis focus markers, etc.). In this article I concentrate on the grammaticalization of the definite article in English, adopting a comparative-contrastive approach (including a wide range of Indo- European languages), given the complexity of the article. Keywords: grammaticalization, definite articles, English, Indo- European languages, definiteness 1. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

New Arguments for Verb Cluster Formation at PF and a Right-Branching VP

New arguments for verb cluster formation at PF and a right-branching VP. Evidence from verb doubling and cluster penetrability* version October 12, 2013; to appear in Linguistic Variation Martin Salzmann, University of Leipzig ([email protected]) Abstract This paper provides new evidence that verb cluster formation in West Germanic takes place post- syntactically. Contrary to some previous accounts, I argue that cluster formation involves linearly adjacent morphosyntactic words and not syntactic sister nodes. The empirical evidence is drawn from Swiss German verb doubling constructions where intriguing asymmetries arise between ascending and descending orders. The approach additionally solves the cluster puzzle with extraposition and topicalization, generates all of the crosslinguistically attested six orders in the verbal complex and correctly predicts which orders are penetrable in which positions. On a more general level, the paper provides arguments for a derivational treatment of verb cluster formation and order variation and adduces important evidence in favor of a right-branching VP. 1 Introduction: Verb clusters in West Germanic In this section I will briefly lay out the central properties of West-Germanic verb clusters. Given the vast literature, I will confine myself to the aspects that will play a role in the ensuing discussion. For a detailed survey both over facts and analyses, the reader is referred to Wurmbrand (2005). West Germanic OV-languages are famous for their verb clusters, i.e. the phenomenon that the verbal elements of a clause all occur together clause-finally (under verb second, where the finite verb moves to C, only the non-finite verbs occur together). -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

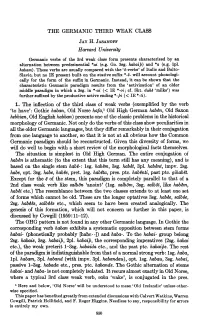

The Germanic Third Weak Class

THE GERMANIC THIRD WEAK CLASS JAY H. JASANOFF Harvard University Germanic verbs of the 3rd weak class form presents characterized by an alternation between predesinential *ai (e.g. Go. 3sg. habai1» and *a (e.g. Ipl. habam). These verbs are usually compared with the 'e-verbs' of Italic and Balto Slavic, but no IE present built on the stative suffix *-e- will account phonologi cally for the form of the suffix in Germanic. Instead, it can be shown that the characteristic Germanic paradigm results from the 'activization' of an older middle paradigm in which a 3sg. in *-ai « IE *-oi; cf. Skt. duh~ 'milks') was further suffixed by the productive active ending *-Pi « IE *-ti). 1. The inflection of the third class of weak verbs (exemplified by the verb 'to have': Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa,! Old High German hab~, Old Saxon hebbian, Old English habban) presents one of the classic problems in the historical morphology of Germanic. Not only do the verbs of this class show peculiarities in all the older Germanic languages, but they differ remarkably in their conjugation from one language to another, so that it is not at all obvious how the Common Germanic paradigm should be reconstructed. Given this diversity of forms, we will do well to begin with a short review of the morphological facts themselves. The situation is simplest in Old High German. The entire conjugation of hab~n is athematic (to the extent that this term still has any meaning), and is based on the single stem hab~-: 1sg. hab~, 3sg. hab~t, 3pl. -

Putting Frisian Names on the Map

GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Second session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 12 of the provisional agenda * Geographical names as culture, heritage and identity, including indigenous, minority and regional languages and multilingual issues Putting Frisian names on the map Submitted by the Netherlands** * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Jasper Hogerwerf, Kadaster GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 Introduction Dutch is the national language of the Netherlands. It has official status throughout the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In addition, there are several other recognized languages. Papiamentu (or Papiamento) and English are formally used in the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom, while Low-Saxon and Limburgish are recognized as non-standardized regional languages, and Yiddish and Sinte Romani as non-territorial minority languages in the European part of the Kingdom. The Dutch Sign Language is formally recognized as well. The largest minority language is (West) Frisian or Frysk, an official language in the province of Friesland (Fryslân). Frisian is a West Germanic language closely related to the Saterland Frisian and North Frisian languages spoken in Germany. The Frisian languages as a group are closer related to English than to Dutch or German. Frisian is spoken as a mother tongue by about 55% of the population in the province of Friesland, which translates to some 350,000 native speakers. In many rural areas a large majority speaks Frisian, while most cities have a Dutch-speaking majority. A standardized Frisian orthography was established in 1879 and reformed in 1945, 1980 and 2015. -

Comments Received for ISO 639-3 Change Request 2015-046 Outcome

Comments received for ISO 639-3 Change Request 2015-046 Outcome: Accepted after appeal Effective date: May 27, 2016 SIL International ISO 639-3 Registration Authority 7500 W. Camp Wisdom Rd., Dallas, TX 75236 PHONE: (972) 708-7400 FAX: (972) 708-7380 (GMT-6) E-MAIL: [email protected] INTERNET: http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/ Registration Authority decision on Change Request no. 2015-046: to create the code element [ovd] Ӧvdalian . The request to create the code [ovd] Ӧvdalian has been reevaluated, based on additional information from the original requesters and extensive discussion from outside parties on the IETF list. The additional information has strengthened the case and changed the decision of the Registration Authority to accept the code request. In particular, the long bibliography submitted shows that Ӧvdalian has undergone significant language development, and now has close to 50 publications. In addition, it has been studied extensively, and the academic works should have a distinct code to distinguish them from publications on Swedish. One revision being added by the Registration Authority is the added English name “Elfdalian” which was used in most of the extensive discussion on the IETF list. Michael Everson [email protected] May 4, 2016 This is an appeal by the group responsible for the IETF language subtags to the ISO 639 RA to reconsider and revert their earlier decision and to assign an ISO 639-3 language code to Elfdalian. The undersigned members of the group responsible for the IETF language subtag are concerned about the rejection of the Elfdalian language. There is no doubt that its linguistic features are unique in the continuum of North Germanic languages. -

English As North Germanic a Summary

Language Dynamics and Change 6 (2016) 1–17 brill.com/ldc English as North Germanic A Summary Jan Terje Faarlund University of Oslo [email protected] Joseph E. Emonds Palacky University [email protected] Abstract The present article is a summary of the book English: The Language of the Vikings by Joseph E. Emonds and Jan Terje Faarlund. The major claim of the book and of this article is that there are lexical and, above all, syntactic arguments in favor of considering Middle and Modern English as descending from the North Germanic language spoken by the Scandinavian population in the East and North of England prior to the Norman Conquest, rather than from the West Germanic Old English. Keywords historical syntax – language contact – history of English – Germanic 1 Introduction The forerunner of Modern English is the 14th-century Middle English dialect spoken in Britain’s East Midlands (Baugh and Cable, 2002: 192–193; Pyles, 1971: 155–158). All available evidence thus indicates that the ancestor of today’s Stan- dard English is the Middle English of what before the Norman Conquest (1066) was called the Danelaw. The texts in this dialect have a recognizable syntax that separates them from a different and also identifiable Middle English sys- tem, broadly termed ‘southern.’ In our book English:TheLanguageoftheVikings (Emonds and Faarlund, 2014), we try to determine the synchronic nature and © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/22105832-00601002 Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:16:31AM via free access 2 faarlund and emonds historic source of this East Midlands version of Middle English, which then also reveals the source of Modern English. -

And Estonian Kalev

Scandinavian Kalf and Estonian Kalev HILDEGARD MUST OLD ICELANDIC SAGAStell us about several prominent :men who bore the name Kalfr, Kalfr, etc.1 The Old Swedish form was written as Kalf or Kalv2 and was a fairly common name in Viking-age Scandinavia. An older form of the same name is probably kaulfR which is found on a runic stone (the Skarby stone). On the basis of this form it is believed that the name developed from an earlier *Kaoulfr which goes back to Proto-Norse *KapwulfaR. It is then a compound as are most of old Scandinavian anthroponyms. The second ele- ment of it is the native word for "wolf," ON"ulfr, OSw. ulv (cf. OE, OS wulf, OHG wolf, Goth. wulfs, from PGmc. *wulfaz). The first component, however, is most likely a name element borrowed from Celtic, cf. Old Irish cath "battle, fight." It is contained in the Old Irish name Cathal which occurred in Iceland also, viz. as Kaoall. The native Germ.anic equivalents of OIr. cath, which go back to PGmc. hapu-, also occurred in personal names (e.g., as a mono- thematic Old Norse divine name Hr;or), and the runic HapuwulfR, ON Hr;lfr and Halfr, OE Heaouwulf, OHG Haduwolf, Hadulf are exact Germanic correspondences of the hybrid Kalfr, Kalfr < *Kaoulfr. However, counterparts of the compound containing the Old Irish stem existed also in other Germanic languages: Oeadwulf in Old English, and Kathwulf in Old High German. 3 1 For the variants see E. H. Lind, Nor8k-i8liind8ka dopnamn och fingerade namn fran medeltiden (Uppsala and Leipzig, 1905-15), e. -

Nonnative Acquisition of Verb Second: on the Empirical Underpinnings of Universal L2 Claims

Nonnative acquisition of Verb Second: On the empirical underpinnings of universal L2 claims Ute Bohnacker Lund University Abstract Acquiring Germanic verb second is typically described as difficult for second-language learners. Even speakers of a V2-language (Swedish) learning another V2-language (German) are said not to transfer V2 but to start with a non-V2 grammar, following a universal developmental path of verb placement. The present study contests this claim, documenting early targetlike V2 production for 6 Swedish ab-initio (and 23 intermediate) learners of German, at a time when their interlanguage syntax elsewhere is nontargetlike (head-initial VPs). Learners whose only nonnative language is German never violate V2, indicating transfer of V2-L1 syntax. Informants with previous knowledge of English are less targetlike in their L3-German productions, indicating interference from non-V2 English. V2 per se is thus not universally difficult for nonnative learners. in press in: Marcel den Dikken & Christina Tortora, eds., 2005. The function of function words and functional categories. [Series: Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today] Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins (pp. 41-77). Nonnative acquisition of Verb Second: On the empirical underpinnings of universal L2 claims Ute Bohnacker Lund University 1. Introduction This paper investigates the acquisition of verb placement, especially verb second (V2), by native Swedish adults and teenagers learning German. Several recent publications (e.g. Platzack 1996, 2001; Pienemann 1998; Pienemann & Håkansson 1999; Håkansson, Pienemann & Sayehli 2002) have claimed that learners, irrespective of their first language (L1), take the same developmental route in the acquisition of syntax of a foreign or second language (L2). -

The Origins of Old English Morphology

Englisches Seminar der Universitat¨ Zurich¨ The Origins of Old English Morphology Hausarbeit der Philosophischen Fakultat¨ der Universitat¨ Zurich¨ im Fach Englische Sprachwissenschaft Referentin: Prof. Dr. Gunnel Tottie Stefan Hofler¨ Wiesenbachstrasse 7a CH-9015 St. Gallen +41 71 / 310 16 65 shoefl[email protected] Zurich,¨ 26. September 2002 Contents Symbols and abbreviations 3 1 Introduction 5 2 Aim and scope 5 3 Literature 6 4 Background: Comparative Indo-European linguistics 7 4.1 Old English in the Indo-European language family . 7 4.1.1 The Indo-European language family and the development of comparative Indo-European linguistics . 7 4.1.2 The Germanic language family . 9 4.1.3 The earliest attestation of Germanic . 10 4.2 Linguistic reconstruction . 11 4.2.1 Internal and external reconstruction . 11 4.2.2 Sound laws . 12 4.2.3 Analogy . 13 5 Conditions of the evolution of Old English morphology 14 5.1 Accent and stress . 14 5.2 Major sound changes from Proto-Indo-European to Old English . 15 5.2.1 Sound changes in stressed syllables . 15 5.2.2 Sound changes in weak syllables . 16 5.3 Morphophonemics . 17 5.3.1 Ablaut . 17 5.3.2 PIE root structure and the laryngeals . 18 6 Exemplification 20 6.1 Noun inflection . 20 6.1.1 a-Stems . 21 6.1.2 o¯ -Stems . 22 6.1.3 i-Stems . 23 6.1.4 u-Stems . 23 6.1.5 n-Stems . 24 1 6.1.6 Consonant stems and minor declensions . 24 6.2 Verb inflection . 25 6.2.1 Strong verbs . -

Yiddish and Relation to the German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Witmore, B.(2016). Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ etd/3522 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YIDDISH AND ITS RELATION TO THE GERMAN DIALECTS by Bryan Witmore Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Kurt Goblirsch, Director of Thesis Lara Ducate, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Bryan Witmore, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis project was made possible in large part by the German program at the University of South Carolina. The technical assistance that propelled this project was contributed by the staff at the Ted Mimms Foreign Language Learning Center. My family was decisive in keeping me physically functional and emotionally buoyant through the writing process. Many thanks to you all. iii ABSTRACT In an attempt to balance the complex, multi-component nature of Yiddish with its more homogenous speech community – Ashekenazic Jews –Yiddishists have proposed definitions for the Yiddish language that cannot be considered linguistic in nature.