Open THESIS SUBMISSION5.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glories of Norman Sicily Betty Main, SRC

The Glories of Norman Sicily Betty Main, SRC The Norman Palace in Palermo, Sicily. As Rosicrucians, we are taught to be they would start a crusade to “rescue” tolerant of others’ views and beliefs. We southern Italy from the Byzantine Empire have brothers and sisters of like mind and the Greek Orthodox Church, and throughout the world, of every race and restore it to the Church of Rome. As they religion. The history of humankind has were few in number, they decided to return often demonstrated the worst human to Normandy, recruit more followers, aspects, but from time to time, in what and return the following year. Thus the seemed like a sea of barbarism, there Normans started to arrive in the region, appeared periods of calm and civilisation. which was to become the hunting ground The era we call the Dark Ages in Europe, for Norman knights and others anxious was not quite as “dark” as may be imagined. for land and booty. At first they arrived as There were some parts of the Western individuals and in small groups, but soon world where the light shone like a beacon. they came flooding in as mercenaries, to This is the story of one of them. indulge in warfare and brigandage. Their Viking ways had clearly not been entirely It all started in the year 1016, when forgotten. a group of Norman pilgrims visited the shrine of St. Michael on the Monte Robert Guiscard and Gargano in southern Italy. After the Roger de Hauteville “pilgrims” had surveyed the fertile lands One of them, Robert Guiscard, of Apulia lying spread out before them, having established his ascendancy over the promising boundless opportunities for south of Italy, acquired from the papacy, making their fortunes, they decided that the title of Duke of Naples, Apulia, Page 1 Calabria, and Sicily. -

Brain Diseases in Greek Meta-Byzantine Society

Journal of Applied Medical Sciences, vol. 2, no. 4, 2013, 53-60 ISSN: 2241-2328 (print version), 2241-2336 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2013 A Socio-Historical Survey of Brain Diseases in Greek Post-Byzantine Society Anastasia K. Kadda1, Nikolas S. Koumpouros2 and Aristotelis P. Mitsos3 Abstract The aim of this study is to present a socio-historical survey of brain diseases and their treatment in Greek post-Byzantine society. For this purpose, research was carried out using Manuscript No. 218 of the Iviron Monastery of Mount Athos. The analysis of this manuscript produced the following conclusions: a) brain diseases are prominently discussed and described in the manuscript, b) the influence of ancient Greek and Roman medicine on Byzantine and on post-Byzantine medical science and society is manifested in the etiology, symptom-matology and therapeutic means of treating brain diseases, c) social factors were seriously taken into account as an important aspect of therapeutic procedure, d) many therapeutic methods were proved to be socially beneficial, e) brain disorders and diseases appear to be diachronic. Keywords: Brain diseases; ancient Greek medicine; Byzantine medicine; social factors; socially beneficial therapeutic means; 1 Introduction The apprehension of health and illness and the type of medicine used at different times and places are models which change according to each epoch and the prevailing social conditions. In other words, the main criteria for a society’s definition of health/illness do not remain static throughout history; instead, they are constantly redefined according to the broad social and cultural frame in which they develop and according to the social concepts of each historical period, thus conferring a social dimension and background to health/illness, a fact which applies to all periods of time in history. -

Cry Havoc Règles Fr 05/01/14 17:46 Page1 Guiscarduiscard

maquette historique UK v2_cry havoc règles fr 05/01/14 17:46 Page1 Guiscarduiscard HISTORY & SCENARIOS maquette historique UK v2_cry havoc règles fr 05/01/14 17:46 Page2 © Buxeria & Historic’One éditions - 2014 - v1.1 maquette historique UK v2_cry havoc règles fr 05/01/14 17:46 Page1 History Normans in Southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th Century 1 - The historical context 1.1 - Southern Italy and Sicily at the beginning of the 11th Century Byzantium had conquered Southern Italy and Sicily in the first half of the 6th century. But by the end of that century, Lombards coming from Northern Italy had conquered most of the peninsula, with Byzantium retaining only Calabria and Sicily. From the middle of the 9th century, the Aghlabid Dynasty of Ifrîquya (the original name of Eastern Maghreb) raided Sicily to take possession of the island. A new Byzantine offensive at the end of the century took back most of the lost territories in Apulia and Calabria and established Bari as the new provincial capital. Lombard territories further north were broken down between three cities led by princes: Capua, Salerno, and Benevento. Further east, Italian duchies of Naples, Amalfi, and Gaeta tried to keep their autonomy through successive alliances with the various regional powers to try and maintain their commercial interests. Ethnic struggles in Sicily between Arabs and Berbers on the one side, and various dynasties on the other side, led to power fragmentation: The island is divided between four rival military factions at the beginning of the 11th century. Beyond its natural boundaries, Southern Italy had to cope with two external powers which were looking to expel Byzantium from what they considered was part of their area of influence: the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire. -

Normans and the Papacy

Normans and the Papacy A micro history of the years 1053-1059 Marloes Buimer S4787234 Radboud University January 15th, 2019 Dr. S. Meeder Radboud University SCRSEM1 V NORMAN2 NOUN • 1 member of a people of mixed Frankish and Scandinavian origin who settled in Normandy from about AD 912 and became a dominant military power in western Europe and the Mediterranean in the 11th century.1 1 English Oxford living dictionaries, <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/norman> [consulted on the 19th of January 2018]. Index INDEX 1 PREFACE 3 ABBREVIATIONS 5 LIST OF PEOPLE 7 CHAPTER 1: STATUS QUAESTIONIS 9 CHAPTER 2: BATTLE AT CIVITATE 1000-1053 15 CHAPTER 3: SCHISM 1054 25 CHAPTER 4: PEACE IN ITALY 1055-1059 35 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION 43 BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 1 2 Preface During my pre-master program at the Radboud University, I decided to write my bachelor thesis about the Vikings Rollo, Guthrum and Rörik. Thanks to that thesis, my interest for medieval history grew and I decided to start the master Eternal Rome. That thesis also made me more enthusiastic about the history of the Vikings, and especially the Vikings who entered the Mediterranean. In the History Channel series Vikings, Björn Ironside decides to go towards the Mediterranean, and I was wondering in what why this affected the status of Vikings. While reading literature about this conquest, there was not a clear matter to investigate. Continuing reading, the matter of the Normans who settled in Italy came across. The literature made it clear, on some levels, why the Normans came to Italy. -

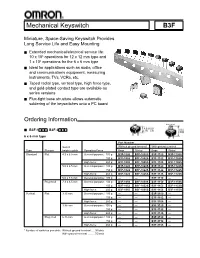

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

Herefore, Incentives Typically Offered and Used for Development Would Be Replaced with the EB-5 Investment

Revised – 9/18/17 CITY OF YPSILANTI REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – ONE SOUTH HURON ST. YPSILANTI, MI 48197 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 7:00 p.m. I. CALL TO ORDER – II. ROLL CALL – Council Member Bashert P A Council Member Robb P A Mayor Pro-Tem Brown P A Council Member Vogt P A Council Member Murdock P A Mayor Edmonds P A Council Member Richardson P A III. INVOCATION – IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE – “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” V. AGENDA APPROVAL – VI. INTRODUCTIONS – VII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION – VIII. REMARKS BY THE MAYOR – IX. PUBLIC HEARING – International Village - Water Street A. Resolution No. 2017-208, approving purchase agreement. B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-209, close public hearing X. PRESENTATIONS – Discussion of Easement Agreement with Michigan Advocacy Program on 15 N. Washington. XI. ORDINANCES – FIRST READING – Ordinance No. 1294 An ordinance to rezone 75 Catherine from Core Neighborhood to Production, Manufacturing & Distribution. A. Resolution No. 2017-210, determination B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-211, close public hearing 1 XII. CONSENT AGENDA – Resolution No. 2017-212 1. Resolution No. 2017–213, approving minutes of August 22 and September 5, 2017. 2. Resolution No. 2017-214, approving the issuance of a blanket permit for window signs of any size for the month of October for businesses that participate with the Eastern Michigan University’s “Follow the Green & White Road” homecoming spirit project. -

“Saint Peter's by the Sea”

“Saint Peter’s by the Sea” A Spiritual Pilgrimage to Rome and Sicily Rome, Vatican City, Taormina, Castelmola, Mount Etna, Castlebuono, Cefalu’, Agrigento, Piazza Armerina and Siracusa A twelve Day Italian Journey April 29th – May 10th, 2019 “To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is not to have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the clue to everything.” ~ Goethe KEYROW TOURS 60 Georgia Road Trumansburg, New York 14886 Tel: 315.491.3711 Day#1: Departure for Italy Monday: April 29th, 2019 In conjunction with AAA Travel (Ithaca, NY), Keyrow Tours is pleased to make all flight arrangements, including primary flights originating from anywhere in the United States, and international flights. We will depart from a major international airport located on the east coast of the United States (most likely Boston) and fly directly into Rome’s Leonardo Da Vinci Airport. Transportation to and from your primary airport of departure is each person’s responsibility. “What is the fatal charm of Italy? What do we find there that can be found nowhere else? I believe it is a certain permission to be human, which other places, other countries, lost long ago.” ~ Erica Jong KEYROW TOURS 60 Georgia Road Trumansburg, New York 14886 Tel: 315.491.3711 Day #2: From Pagan Temples to Patrimonial Churches Tuesday: April 30th, 2019 Morning arrival at Leonardo Da Vinci Airport, Rome After passport control and collecting our luggage, private minivans will transfer us to our hotel, located in Rome’s historical center. Pranzo! (Light lunch included) Time to shower and unpack The Centro Storico (Historic Center) A.) Campo Dei Fiori Rome’s daily farmer’s market is a five minute walk from our hotel: fresh vegetables and fruits, cheese, meats and fish. -

ROGER II of SICILY a Ruler Between East and West

. ROGER II OF SICILY A ruler between east and west . HUBERT HOUBEN Translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org Originally published in German as Roger II. von Sizilien by Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1997 and C Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1997 First published in English by Cambridge University Press 2002 as Roger II of Sicily English translation C Cambridge University Press 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Bembo 10/11.5 pt. System LATEX 2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Houben, Hubert. [Roger II. von Sizilien. English] Roger II of Sicily: a ruler between east and west / Hubert Houben; translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn. p. cm. Translation of: Roger II. von Sizilien. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65208 1 (hardback) isbn 0 521 65573 0 (paperback) 1. Roger II, King of Sicily, d. -

Middle Ages Reference Library: Cumulative Index 10 987654321 Printed Intheunitedstatesofamerica Produced Bypermissionofthecorbiscorporation

MA.cu-ttlpgs. qxp 3/31/04 10:17 AM Page 1 Reference Library Cumulative Index MA.cu-ttlpgs. qxp 3/31/04 10:17 AM Page 3 Reference Library Cumulative Index Cumulates Indexes For: Middle Ages: Almanac Middle Ages: Biographies Middle Ages: Primary Sources Judy Galens, Index Coordinator Staff Judy Galens, Index Coordinator Pamela A. E. Galbreath, Senior Art Director Kenn Zorn, Product Design Manager Marco Di Vita, Graphix Group, Typesetting This publication is a creative work fully protected by all applicable copyright laws, as well as by misappropriation, trade secret, unfair competition, and other applicable laws. The author and editors of this work have added value to the underlying factual material herein through one or more of the following: unique and original selection, coordination, expression, arrangement, and classification of the in- formation. All rights to the publication will be vigorously defended. Copyright ©2001 U•X•L, an imprint of The Gale Group All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. ISBN 0-7876-5575-9 The front cover photograph of crusaders disembarking in Egypt was re- produced by permission of the Corbis Corporation. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Middle Ages Reference Library: Cumulative Index Middle Ages Reference Library Cumulative Index A=Middle Ages: Almanac B=Middle Ages: Biographies PS=Middle Ages: Primary Sources A Abraham Bold type indicates set title, A 66 main entries, and their page Aachen Abu al-Abbas numbers. A 34–36 A 37 B 1: 64, 66, 66 (ill.), 2: 205 Abu Bakr Italic type indicates volume Abbasid caliphate A 68 numbers. -

Byzantine Medicine: the Finlayson Memorial

THE GLASGOW MEDICAL JOURNAL. No. Y. November, 1913. ORIGINAL ARTICLES.] BYZANTINE MEDICINE: THE FINLA^g^r- MEMORIAL LECTURE.1 By Sir THOMAS CLIFFORD ALLBUTT, K.C.B., LL.D., D.Sc., M.D.r Regius Professor of Physic, Cambridge. Mr. Chairman, Ladies, and Gentlemen,?We are gathered together to-day in memory of James Finlayson, a wise physician and a gentle scholar. More than once, with the art of the scholar and the love of the benefactor, he displayed to me some of the treasures of your library. I would that my lecture to-day were more worthy of him. It was a fine saying of that great historian and physician, Charles Daremberg, that in the domain of mind, as in that of matter, we cannot believe in spontaneous generation. The springs of life and the development of life; its order in variety; its integrations of ever new and broader functions of the world around it; its compass and comprehension; 1 Delivered in the Faculty Hall on Friday, 6th June, 1913. No. 5. X Vol. LXXX. 322 Sir Clifford Allbutt?Byzantine Medicine: these growing powers, these rich and manifold qualities have their lineage ; they have their origin in the past; they have their ancestry, their laws of tradition, their channels of nurture; and if animal development cannot spring directly from the clay into high wrought organs and various functions, neither likewise can the spiritual life. It, too, must have its lineage, its race; from parent to parent the social life is engendered and nurtured; from generation to generation it dwells upon its gradual houses, families, tribes, and rejoices in its children; it learns to reflect upon its history in the past, and from that vantage to reach forth into its future and to imagine its destiny. -

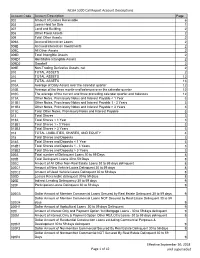

NCUA 5300 Call Report Account Descriptions Page 1 of 42 Effective

NCUA 5300 Call Report Account Descriptions Account Code Account Description Page 002 Amount of Leases Receivable 6 003 Loans Held for Sale 1 007 Land and Building 2 008 Other Fixed Assets 2 009 Total Other Assets 2 009A Accrued Interest on Loans 2 009B Accrued Interest on Investments 2 009C All Other Assets 2 009D Total Intangible Assets 2 009D1 Identifiable Intangible Assets 2 009D2 Goodwill 2 009E Non-Trading Derivative Assets, net 2 010 TOTAL ASSETS 2 010 TOTAL ASSETS 12 010 TOTAL ASSETS 13 010A Average of Daily Assets over the calendar quarter 12 010B Average of the three month-end balances over the calendar quarter 12 010C The average of the current and three preceding calendar quarter-end balances 12 011A Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable < 1 Year 3 011B1 Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable 1 - 3 Years 3 011B2 Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable > 3 Years 3 011C Total Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable 3 013 Total Shares 3 013A Total Shares < 1 Year 3 013B1 Total Shares 1 - 3 Years 3 013B2 Total Shares > 3 Years 3 014 TOTAL LIABILITIES, SHARES, AND EQUITY 4 018 Total Shares and Deposits 3 018A Total Shares and Deposits < 1 Year 3 018B1 Total Shares and Deposits 1 - 3 Years 3 018B2 Total Shares and Deposits > 3 Years 3 020A Total number of Delinquent Loans 30 to 59 Days 8 020B Total Delinquent Loans 30 to 59 Days 8 020C Amount of All Other Non-Real Estate Loans 30 to 59 days delinquent 8 020C1 Amount of New Vehicle Loans Delinquent 30 to 59 days 8 020C2 Amount of Used -

Middle School Bee Final Round Regulation Questions

IHBB European Championships Bee 2018-2019 Bee Final Round Middle School Bee Final Round Regulation Questions (1) One man who held this position was killed in the 10.26 incident by the director of the KCIA. That man’s daughter later became the first woman to hold this position until she was impeached in 2016. The first man to hold this position led his country through a conflict with a northern neighbor and was named Syngman Rhee. Park Chung Hee and Park Geun-Hye held, for the point, what position whose holders live in the Blue House in Seoul? ANSWER: President of South Korea (Accept President of the Republic of Korea, accept Daehan Minguk Daetongnyeong) (2) The state of Krajina [kry-ee-nah] failed to break away from this country, which secured its independence after winning the Battle of Drvar in Operation Storm. Franjo Tudman led this country to victory against Slobodan Milosevic’s forces, then pushed into Bosnia in 1995. For the point, name this country that gained its independence after the breakup of Yugoslavia and established its capital at Zagreb. ANSWER: Croatia (3) After the battle, the loser was given an alcoholic drink as a symbol that he would be spared, which he misinterpreted by passing the glass to his ally, Reynald of Chatillon. Five months after this battle, Baldwin IV routed the winner of this battle at Montgisard. This battle, which was named for an extinct volcano that had two peaks, allowed its winner to recapture Jerusalem later that year. For the point, name this 1187 battle where Saladin crushed the crusaders.