UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thestudentissue

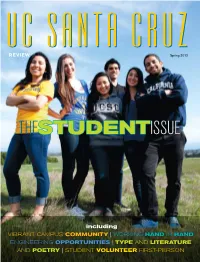

UC SANTA CRUZSpring 2013 UC SANTA CRUZREVIEW THESTUDENTISSUE including VIBRANT CAMPUS COMMUNITY | WORKING HAND IN HAND ENGINEERING OPPORTUNITIES | TYPE AND LITERATURE AND POETRY | STUDENT VOLUNTEER FIRST-PERSON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ Chancellor George Blumenthal Vice Chancellor, University Relations Donna Murphy UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW Spring 2013 photo: jim mackenzie Editor Gwen Jourdonnais Creative Director Lisa Nielsen Art Director/Designer Linda Knudson (Cowell ’76) From the Chancellor Associate Editor Dan White Cover Photo Carolyn Lagattuta They are smart and hardworking. The admitted Tenacious, imaginative, freshman class for fall 2012 had an average high Photography school GPA of nearly 3.8. Carolyn Lagattuta conscientious—and bright! Jim MacKenzie Our students are also whimsical, fun, creative, Elena Zhukova When I walk around campus, I’m gratified and and innovative—think hipster glasses and flowered inspired by UCSC students. I see students en- velvet Doc Martens—in addition to being tutors, Contributors gaged in the full range of academic and creative mentors, and volunteers. Amy Ettinger Guy Lasnier (Merrill ’78) pursuits, as well as extracurricular activities. This They are active—and we’re ready for them, with Scott Rappaport issue of Review celebrates our students. more than 100 student organizations, 14 men’s Tim Stephens Peggy Townsend Who are today’s students? and women’s NCAA intercollegiate teams, and a Dan White To give you an idea, consider our most recent wide variety of athletic clubs, intramural leagues, and rec programs. Produced by applicant pool. More than 46,000 prospective UC Santa Cruz undergraduates—the most ever—applied for admis- Banana Slugs revel in our broad academic offer- Communications sion to UCSC for the fall 2013 quarter. -

LYDIA ZEPEDA E-Mail: [email protected]

LYDIA ZEPEDA http://www.localandorganicfood.org e-mail: [email protected] I. EXPERIENCE Fulbright Senior Scholar in Economics, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid January-May 2018 Professor Emerita, University of Wisconsin-Madison Nov 2017-present Faculty affiliate, Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies 1999-2020 Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Consumer Science July 2001-Nov 2017 Retired December 1, 2017 (Sabbaticals: academic years 2010-11, 2003-04) Faculty affiliate, Center for European Studies 2014-2017 Faculty affiliate, Department of Urban and Regional Planning 2013-2015 Faculty affiliate, Development Studies 1999-2017 Faculty affiliate, Gender and Women’s Studies 2011-2017 Faculty affiliate, Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program 1995-2017 Research affiliate, Community and Regional Food Systems Project 2012-2017 Chair, Development Studies PhD, University of Wisconsin-Madison May 2002-August 2003 Director, Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems January 2001-April 2002 University of Wisconsin-Madison Economist, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome October 1996-December 1998 Agricultural Sector in Economic Development Service Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison (On leave October 1996-December 1998) Department of Consumer Science July 1995–June 2001 Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Researcher, University of Costa Rica August-December 1992 Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison (On leave November 1991-December 1992) Department of Consumer Science February - June 1995 Department of Agricultural Economics November 1988 - June 1995 Revenue Planning Administrator, General Telephone of the Northwest October 1984-July 1986 Research and Teaching Assistant, University of California at Davis Academic years 1986-88 Department of Agricultural Economics and 1982-84 II. EDUCATION Ph.D. -

Trend in Engineering

theTrend Autumn 2006: Volume 56, Issue 2 in engineering Hot Ideas out of the lab and into the world... Page 6 Message from the Dean News Spotlight Great Expectations As fall quarter kicks off, you can “Ideas to Innovation” (i2i) summit feel the energy of new and returning attended by 65 top executives of students. As a new kid myself, I’m as area companies as well as key local, excited as a first-year student. state and federal leaders. Among a Since mid-August, I’ve met with number of things, we talked about many faculty and staff members UW Engineering and its excellent in a series of “boot camps.” Each track record in taking innovations session introduced me to more of to market. As dean, I will strengthen the college’s work. Lots of days, it these partnerships. was intense, like drinking from a fire UW Engineering has a strong How do students fit into this hose. We hashed out our strengths, culture of interdisciplinary teamwork picture? Great expectations. We train our challenges, our plans for re- and research innovation, but the students to be more than competent search and education initiatives, all bar needs to be higher, with goals engineers seeking design or project in big chunks. It was exhausting and stretching to the global arena. This management jobs. We prepare them exhilarating, but gradually a theme requires significant resources, always to work in a complex, highly tech- emerged: the importance of commu- a major challenge. nological world. It means more nity, not just our internal university An August 22 feature article in undergraduates will participate in community, but our connection to The Seattle Times reported that interdisciplinary research projects the communities where we live. -

Cumulative Bio-Bibliography University of California, Santa Cruz June 2020

Cumulative Bio-Bibliography University of California, Santa Cruz June 2020 Puragra Guhathakurta Astronomer/Professor University of California Observatories/University of California, Santa Cruz ACADEMIC HISTORY 1980–1983 B.Sc. in Physics (Honours), Chemistry, and Mathematics, St. Xavier’s College, University of Calcutta 1984–1985 M.Sc. in Physics, University of Calcutta Science College; transferred to Princeton University after first year of two-year program 1985–1987 M.A. in Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University 1987–1989 Ph.D. in Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University POSITIONS HELD 1989–1992 Member, Institute for Advanced Study, School of Natural Sciences 1992–1994 Hubble Fellow, Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University 1994 Assistant Astronomer, Space Telescope Science Institute (UPD) 1994–1998 Assistant Astronomer/Assistant Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 1998–2002 Associate Astronomer/Associate Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 2002–2003 Herzberg Fellow, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council of Canada, Victoria, BC, Canada 2002– Astronomer/Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 2009– Faculty Director, Science Internship Program, University of California, Santa Cruz 2012–2018 Adjunct Faculty, Science Department, Castilleja School, Palo Alto, CA 2015 Visiting Faculty, Google Headquarters, Mountain View, CA 2015– Co-founder, Global SPHERE (STEM Programs for High-schoolers Engaging in Research -

In Engineering Educa- Morrison

T H E trend I N EN G I N E E R I N G Fall 2004 Two Debts of Gratitude Lead to ME’s First Endowed Chair Two debts of gratitude, one dating to a three-month trek from northern China to Mao World War II and one to the 1960s, Zedong’s headquarters in Yenan, where a U.S. plane have culminated in a $2 million gift picked them up. Morrison had no way to pay back for Mechanical Engineering. The gift the guerillas for saving his life, so he decided that, honors James Morrison, somehow, he had to “pay back the a retired ME professor, human race.” through the generosity After the war he signed on as of Henry Schatz, CEO an instructor in UW Mechanical of General Plastics Engineering while earning his masters Manufacturing Co. degree. He discovered a talent and in Tacoma. The gift love for teaching and won accolades includes $1 million to from students. Morrison confined his endow a chair named research to the summers and devoted Henry Schatz (BS ME, ‘64) for Morrison and $1 full attention to his students during toured the ME laboratories million to fund an endowment for the academic year. It was a way to during a campus visit in undergraduate scholarships. repay that debt and an “opportunity August. The saga begins in China during to help a lot of people.” World War II when Morrison and 10 When Schatz enrolled in the others bailed out of a crippled B-29. 1960s, Morrison was a full professor Communist guerillas smuggled the Lt. -

Electromagnetics00whinrich.Pdf

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California College of Engineering Oral History Series John R. Whinnery RESEARCHER AND EDUCATOR IN ELECTROMAGNETICS, MICROWAVES, AND OPTOELECTRONICS, 1935-1995; DEAN OF THE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, UC BERKELEY, 1959-1963 With an Introduction by Donald 0. Pederson Interviews Conducted by Ann Lage in 1994 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and John R. Whinnery dated February 9, 1994. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Karl S. Pister: UCSC Chancellorship, 1991-1996 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7pn93507 Authors Pister, Karl Jarrell, Randall Regional History Project, UCSC Library Publication Date 2000 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7pn93507#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction The Regional History Project conducted eight interviews with UCSC Chancellor Karl S. Pister just prior to his retirement on June 30, 1996, as part of its University History series. Pister was originally named as the campus’s sixth chancellor for an interim two-year appointment by UC President David P. Gardner in August, 1991, after the resignation of UCSC Chancellor Robert B. Stevens. In March, 1992, the UC Regents approved President Gardner’s recommendation for Pister’s regular appointment as chancellor. Prior to his appointment, Pister had spent his entire academic life at UC Berkeley—thirty years as a faculty member and fifteen years as an academic administrator—and as a seasoned veteran of the UC system and its bureaucracy, he knew the workings of the Academic Senate, the key figures in the University administration, and the institution’s policies and culture, all of which stood him in good stead at UC Santa Cruz. Born in Stockton, California, Pister received his B.S. (1945) and M.S. degrees (1948) in civil engineering at UC Berkeley. In 1952 he received his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois in theoretical and applied mechanics. He began his career at UC as a lecturer in 1947, and in 1952 joined the faculty of the College of Engineering where he had a distinguished career as a professor of engineering. -

Meet UCSC's Ninth Chancellor: Denice D. Denton

UCUC SANTASANTA CRUZCRUZ REVIEW Spring 2005 Meet UCSC’s Ninth Chancellor: Denice D. Denton Celebrating 40 years of alumni achievement Providing financial support for students UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW UC Santa Cruz Q&A: Chancellor Review 8 Denice D. Denton Chancellor New chancellor Denice Denton Denice D. Denton describes the UCSC qualities Vice Chancellor, University Relations Ronald P. Suduiko that attracted her to the post— and that make her optimistic Associate Vice Chancellor Communications about the campus’s future. Elizabeth Irwin Editor schraub paul Jim Burns Art Director 40 Years... Jim MacKenzie 10 and Counting Associate Editors Julie Packard, executive Mary Ann Dewey Jeanne Lance director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, is one of many Writers Louise Gilmore Donahue alumni we celebrate to mark Jennifer McNulty the campus’s 40th year. Scott Rappaport Jennifer Dunn, student Doreen Schack Telephone Outreach Program Tim Stephens r. r. jones r. r. Cover Photography Cornerstone Paul Schraub (B.A. Politics ’75, Stevenson) 22 Offi ce of University Relations Campaign Update Carriage House Raising money for scholarships When a student calls, say ‘YES.’ University of California 1156 High Street and fellowships, which support Santa Cruz, CA 95064-1077 students like Charles Tolliver, is a Voice: 831.459.2501 priority of UCSC’s fi rst campus- Fax: 831.459.5795 wide fundraising campaign. tudents are making an all-out effort this year to raise funds for E-mail: [email protected] scholarships and fellowships at UC Santa Cruz. They are asking Web: review.ucsc.edu S Produced by UC Santa Cruz Public Affairs jim mackenzie you to help by making a generous pledge 3/05(05-045/89.3M) Departments to the $50 million Cornerstone Campaign. -

Sixthchancellor00bowkrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral -History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Albert H. Bowker SIXTH CHANCELLOR, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1971-1980; STATISTICIAN, AND NATIONAL LEADER IN THE POLICIES AND POLITICS OF HIGHER EDUCATION With an Introduction by Joseph L. Hodges Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1991 Copyright 1995 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the Vest, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Albert H. Bowker dated April 3, 1993. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Appointments and Staff Changes

NEWS AND NOTES 985 The Fifth World Congress of The International 1964, at a place to be determined later. Political Science Association was held at the The Fifteenth Annual meeting of the New UNESCO building in Paris, France, September York Political Science Association was held at 26-30, 1961. Over five hundred political scientists Cornell University on April 21 and 22, 1961. attended and there was representation from over Panel sessions were devoted to "Government and https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400126590 forty countries. The Congress was held under the Resources Development," and "Politics of De- . auspices of the Prime Minister, the Minister of veloping Areas." At the dinner session Laurin Foreign Affairs, and the Minister of National Henry of the Brookings Institution discussed Education of France. Professor J.-J. Chevallier, "Presidential Transition." Officers of the Associa- President of the French Political Science Asso- tion for 1961-62 are: William R. Willoughby, St. ciation, headed the Organizing Committee. Five Lawrence University, president; Channing Rich- series of panel discussions dealt with (1) the con- ardson, Hamilton College, vice president; Fred- tribution of studies of political behavior; (2) the erick T. Bent, Cornell University, secretary political problems of polyethnic states; (3) ad- treasurer; and James Riedel (Union College), ministrative problems in the field of nuclear Frederick Englemann (Alfred University), and energy; (4) technocracy and the role of experts in Herbert Rosenbaum (Hofstra College), members government; and (5) civil-military relations in of the excutive council. https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms the field of foreign policy making. Norman A joint meeting of the Western Political Science Chester, Warden of Nuffield College, Oxford, was Association and the Pacific Northwest Political elected President of IPSA for a three-year term, Science Association will be held March 23-24 at succeeding Jacques Chapsal, Directeur de l'ln- Portland State College. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society

Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings and conferences approved prior to the date this issue insofar as is possible. Instructions for submission of abstracts can be found in the went to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings with the Mathe January 1993 issue of the Notices on page 46. Abstracts of papers to be presented at matical Association of America. the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Abstracts of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the Island. on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the abstracts for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meeting, earlier than that specified below. Meetings Abstract Program Meeting# Date Place Deadline Issue 893 June 16-18, 1994 Eugene, Oregon Expired May-June 894 August 15-17, 1994 (96th Summer Meeting) Minneapolis, Minnesota May 17 July-August 895 * October 28-29, 1994 Stillwater, Oklahoma August 3 October 896 * November 11-13, 1994 Richmond, Virginia August 3 October 897 January 4-7, 1995 (101st Annual Meeting) San· Francisco, California OctoberS December 898 March 4-5, 1995 Hartford, Connecticut 899 March 17-18, 1995 Orlando, Florida 900 March 24-25, 1995 Chicago, Illinois August 6-8, 1995 (97th Summer Meeting) Burlington, Vermont October -

DOCUMENT RESUME Developing a Digital National Library For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 425 928 SE 061 938 TITLE Developing a Digital National Library for Undergraduate Science, Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology Education. Report of a Workshop. INSTITUTION National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, Washington, DC. Center for Science, Mathematics, and Engineering Education. ISBN ISBN-0-309-05977-1 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 138p. CONTRACT DUE-9727710 AVAILABLE FROM National Academy Press, 2101 Constitution Avenue NW, Lock Box 285, Washington, DC 20055; Tel: 800-624-6242 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.nap.edu PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Economic Factors; Educational Research; *Electronic Libraries; Engineering Education; Higher Education; *Information Technology; Libraries; *Library Science; Mathematics Education; Science Education; Technology Education; *Undergraduate Study ABSTRACT In collaboration with the National Research Council's (NRC's) Computer Science and Telecommunications Board, the Center for Science, Mathematics, and Engineering Education responded to a request from the National Science Foundation (NSF) by forming a project steering committee consisting of representatives from the NRC's four postsecondary boards and committees. The Steering Committee commissioned 10 "white papers" from individuals with expertise in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology education, technological aspects of digital libraries, library science, and economic and legal aspects of this rapidly evolving area of knowledge and research. These commissioned papers served as the basis for plenary and break-out discussions at a workshop that was held at the National Academy of Sciences on August 7-8, 1997. Issues considered included curricular, pedagogical, and user issues; logistic and technology issues; and economic and legal issues. Appendices include the commissioned papers, workshop agenda, and a list of workshop participants and NSF observers.