UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thestudentissue

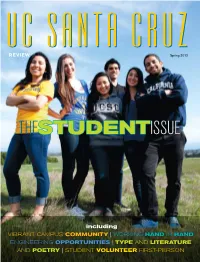

UC SANTA CRUZSpring 2013 UC SANTA CRUZREVIEW THESTUDENTISSUE including VIBRANT CAMPUS COMMUNITY | WORKING HAND IN HAND ENGINEERING OPPORTUNITIES | TYPE AND LITERATURE AND POETRY | STUDENT VOLUNTEER FIRST-PERSON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ Chancellor George Blumenthal Vice Chancellor, University Relations Donna Murphy UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW Spring 2013 photo: jim mackenzie Editor Gwen Jourdonnais Creative Director Lisa Nielsen Art Director/Designer Linda Knudson (Cowell ’76) From the Chancellor Associate Editor Dan White Cover Photo Carolyn Lagattuta They are smart and hardworking. The admitted Tenacious, imaginative, freshman class for fall 2012 had an average high Photography school GPA of nearly 3.8. Carolyn Lagattuta conscientious—and bright! Jim MacKenzie Our students are also whimsical, fun, creative, Elena Zhukova When I walk around campus, I’m gratified and and innovative—think hipster glasses and flowered inspired by UCSC students. I see students en- velvet Doc Martens—in addition to being tutors, Contributors gaged in the full range of academic and creative mentors, and volunteers. Amy Ettinger Guy Lasnier (Merrill ’78) pursuits, as well as extracurricular activities. This They are active—and we’re ready for them, with Scott Rappaport issue of Review celebrates our students. more than 100 student organizations, 14 men’s Tim Stephens Peggy Townsend Who are today’s students? and women’s NCAA intercollegiate teams, and a Dan White To give you an idea, consider our most recent wide variety of athletic clubs, intramural leagues, and rec programs. Produced by applicant pool. More than 46,000 prospective UC Santa Cruz undergraduates—the most ever—applied for admis- Banana Slugs revel in our broad academic offer- Communications sion to UCSC for the fall 2013 quarter. -

Electromagnetics00whinrich.Pdf

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California College of Engineering Oral History Series John R. Whinnery RESEARCHER AND EDUCATOR IN ELECTROMAGNETICS, MICROWAVES, AND OPTOELECTRONICS, 1935-1995; DEAN OF THE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, UC BERKELEY, 1959-1963 With an Introduction by Donald 0. Pederson Interviews Conducted by Ann Lage in 1994 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and John R. Whinnery dated February 9, 1994. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title From Complex Organisms to a Complex Organization: An Oral History with UCSC Chancellor M.R.C. Greenwood, 1996-2004 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9hv2j5t9 Authors Reti, Irene H. Greenwood, M.R.C. Publication Date 2014-04-03 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Complex Organisms to a Complex Organization: An Oral History with UCSC Chancellor M.R.C. Greenwood, 1996-2004 Interviewed by Randall Jarrell and Irene Reti Edited by Irene Reti Santa Cruz University of California, Santa Cruz University Library 2014 This oral history is covered by a copyright agreement between M.R.C. Greenwood and the Regents of the University of California dated March 7, 2014. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the University Library’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the University Librarian and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. For permission contact: Irene Reti [email protected] or Regional History Project, McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA, 95064. Phone: 831-459-2847 Table of Contents Interview History 1 Associate Director for Science in the White House 6 Arriving at the University of California, Santa Cruz 21 Meeting UCSC Faculty and Staff 31 Changing UCSC’s Image 34 Relations -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Karl S. Pister: UCSC Chancellorship, 1991-1996 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7pn93507 Authors Pister, Karl Jarrell, Randall Regional History Project, UCSC Library Publication Date 2000 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7pn93507#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction The Regional History Project conducted eight interviews with UCSC Chancellor Karl S. Pister just prior to his retirement on June 30, 1996, as part of its University History series. Pister was originally named as the campus’s sixth chancellor for an interim two-year appointment by UC President David P. Gardner in August, 1991, after the resignation of UCSC Chancellor Robert B. Stevens. In March, 1992, the UC Regents approved President Gardner’s recommendation for Pister’s regular appointment as chancellor. Prior to his appointment, Pister had spent his entire academic life at UC Berkeley—thirty years as a faculty member and fifteen years as an academic administrator—and as a seasoned veteran of the UC system and its bureaucracy, he knew the workings of the Academic Senate, the key figures in the University administration, and the institution’s policies and culture, all of which stood him in good stead at UC Santa Cruz. Born in Stockton, California, Pister received his B.S. (1945) and M.S. degrees (1948) in civil engineering at UC Berkeley. In 1952 he received his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois in theoretical and applied mechanics. He began his career at UC as a lecturer in 1947, and in 1952 joined the faculty of the College of Engineering where he had a distinguished career as a professor of engineering. -

Sixthchancellor00bowkrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral -History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Albert H. Bowker SIXTH CHANCELLOR, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1971-1980; STATISTICIAN, AND NATIONAL LEADER IN THE POLICIES AND POLITICS OF HIGHER EDUCATION With an Introduction by Joseph L. Hodges Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1991 Copyright 1995 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the Vest, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Albert H. Bowker dated April 3, 1993. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Appointments and Staff Changes

NEWS AND NOTES 985 The Fifth World Congress of The International 1964, at a place to be determined later. Political Science Association was held at the The Fifteenth Annual meeting of the New UNESCO building in Paris, France, September York Political Science Association was held at 26-30, 1961. Over five hundred political scientists Cornell University on April 21 and 22, 1961. attended and there was representation from over Panel sessions were devoted to "Government and https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400126590 forty countries. The Congress was held under the Resources Development," and "Politics of De- . auspices of the Prime Minister, the Minister of veloping Areas." At the dinner session Laurin Foreign Affairs, and the Minister of National Henry of the Brookings Institution discussed Education of France. Professor J.-J. Chevallier, "Presidential Transition." Officers of the Associa- President of the French Political Science Asso- tion for 1961-62 are: William R. Willoughby, St. ciation, headed the Organizing Committee. Five Lawrence University, president; Channing Rich- series of panel discussions dealt with (1) the con- ardson, Hamilton College, vice president; Fred- tribution of studies of political behavior; (2) the erick T. Bent, Cornell University, secretary political problems of polyethnic states; (3) ad- treasurer; and James Riedel (Union College), ministrative problems in the field of nuclear Frederick Englemann (Alfred University), and energy; (4) technocracy and the role of experts in Herbert Rosenbaum (Hofstra College), members government; and (5) civil-military relations in of the excutive council. https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms the field of foreign policy making. Norman A joint meeting of the Western Political Science Chester, Warden of Nuffield College, Oxford, was Association and the Pacific Northwest Political elected President of IPSA for a three-year term, Science Association will be held March 23-24 at succeeding Jacques Chapsal, Directeur de l'ln- Portland State College. -

UA 50 UCSC Photography Services Inventory For

UA 50 UCSC Photography Services - Photographic Materials Job Number Date Description Negatives Contact Sheets Prints Photographer 18 1965 Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 20 1965 College III (Crown College) renderings of residence halls. Box 1: partial Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 24 1965 Library - renderings of University Library: 45-12; architectural plans of University Library Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 27 1965 Campus buildings, forest Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 30 12/1/1965 Field house, interior Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 34 1966 Central Services Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 37 1966 Sorensen Portrait Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 40 1966 Madrigal singers, student musicians Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 45 1966 Graduate students, scientific equipment Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 47 1966 Jasper Rose, professor of art history, provost of Cowell College Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 50 1966 Kenneth V. Thimann, professor of biology, provost of Crown College Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 54 1966 Audiovisual staff Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 58 1966 Faculty lounge Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 61 1966 Construction progress, Stevenson College Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 65 1966 Security, fingerprints, -

Unhappy in Its Own Way an Institutional Biography of UC Santa Cruz

Unhappy in Its Own Way An Institutional Biography of UC Santa Cruz Ronnie D. Lipschutz Summary Reports from the many outposts of higher education across the United States and the world reflect often-lurid power struggles, among faculty, staff, administrators and even institutional governors. No one is very interested in the normal everyday operation of organizations, most which is pretty dull. When change is thought to be required, administrations tend to launch centralized initiatives that seek to reform or quickly quickly how the organization operates. This, however, is much like trying to turn a supertanker on a dime. It cannot be done. Moreover, such plans, if they are implemented at all, are likely to turn out quite differently from the original vision, with subsequent planning attempts to undo the damage caused by earlier plans. In the corporate world, planning is passé, and the notion that higher education is “in crisis” has led to a continuing craze for rapid institutional innovation through new management strategies and “leadership,” both seen as simply individual skills that can be learned and deployed. These have come to substitute for careful consideration of the many factors and forces that universities face, both internally and externally. Do such things work? This book serves two purposes: First, it a reflection on the world faced by universities across the United States, 20 years into the 21st century. The so-called crisis of higher education in the United States has come to occupy many minds and managers, including faculty, administrators, pundits, politicians, scandalmongers and even Presidents. Whether there is such a crisis is questionable, in part because it is linked to larger changes in political economies, between the end of World War II and today, that made higher education possible on a large scale and seem defective today. -

University of California, Santa Cruz Dean E. Mchenry Library DEAN

University of California, Santa Cruz Dean E. McHenry Library DEAN E. McHENRY VOLUME II THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ: ITS ORIGINS, ARCHITECTURE, ACADEMIC PLANNING AND EARLY FACULTY APPOINTMENTS 1958-1968 Interviewed and Edited by Elizabeth Spedding Calciano Santa Cruz 1974 ii Chancellor Dean E. McHenry Seated at a desk on the UCSC campus meadows March 2, 1962 iii All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Dean E. McHenry, dated February 20, 1971. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes upon his death unless he gives written permission to the Office of the University Librarian and/or the Office of the Regional History Project that the manuscript is to be available at an earlier date. With the exception of certain rights granted to Dean E. McHenry, all literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The University Library of the University of California, Santa Cruz. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the University Librarian of the University of California, Santa Cruz. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume II INTRODUCTION ............................................................. VII APRIL 3, 1968 9:15 A.M. ................................................... 1 UC STATEWIDE .......................................................................................................................................................1 1957 All-University Faculty Conference -

What a Difference a Year Makes Our Partners

OUR PARTNERS UC SANTA CRUZ A progress report on philanthropy of the UC Santa Cruz Foundation, 2007–08 What a difference a year makes Entering my second year as president, I’m astounded by the differences a year can make. Most notably, we saw the inauguration of Chancellor George Blumenthal, who honored UCSC’s founders by reminding us that we were to become a “campus for the next century”—a campus of brilliant scholars dedicated to educating tomorrow’s leaders and breaking new ground in their chosen research fields. It is gratifying to see faculty, students, and staff embarking on bold programs to build the world’s largest telescope, protect coastal and marine communities, bring health services to under- served populations, and develop storage technology to securely house increasingly complex data sets. True to the founders’ vision, the continuing emphasis on undergraduate education leads to a disproportionately high percentage of alumni who pursue graduate and professional degrees (not to mention, the receipt of Pulitzer, MacArthur, and countless other awards). These achievements, however, would not have been possible without your support. Gifts to the campus increased 25 percent last year, and the Foundation is rapidly mobilizing itself to launch even more ambitious efforts in the coming years. Supporting UCSC’s unique brand of scholar- ship is testimony to your commitment and passion for seeking excellence amidst the beauty of the redwoods on the hill. On behalf of the Board, I cannot thank you enough for your dedication and support. What can we do together to make next year even better? Gordon Ringold President, UC Santa Cruz Foundation 1 ■ Other Organizations: $2,587,213 (8.2%) FINANCIAL OVERVIEW Private gifts making a difference With over $31.5 million in private contributions during 2007–08, your support helped make this the third-highest fundraising year in UCSC history. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Dean McHenry: Volume III: the University of California, Santa Cruz, Early Campus History, 1958-1969 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6rv1h8fv Authors Regional History Project, UC Santa Cruz Library McHenry, Dean E Publication Date 1987 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6rv1h8fv#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, Santa Cruz University Library DEAN E. McHENRY VOLUME III UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ: EARLY CAMPUS HISTORY 1958-1969 Interviewed by Elizabeth Spedding Calciano Edited by E.S.C. and Randall Jarrell Santa Cruz 1987 ii Dean E. McHenry Inauguration as Chancellor University of California, Santa Cruz Upper Quarry May 3, 1966 iii All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Dean E. McHenry, dated February 20, 1971. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes upon his death unless he gives written permission to the Office of the University Librarian and/or the Office of the Regional History Project that the manuscript is to be available at an earlier date. With the exception of certain rights granted to Dean E. McHenry, all literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The University Library of the University of California, Santa Cruz. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the University Librarian of the University of California, Santa Cruz. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume III INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... VIII JULY 10, 1968 9:45 A.M. -

Regional History Project, University Library UC Santa Cruz

Regional History Project, University Library UC Santa Cruz Title: Allan J. Dyson: Managing the UCSC Library, 1979-2003 Author: Dyson, Allan J. Reti, Irene Publication Date: July 1, 2006 Series: Other Recent Work Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3nj8f076 Keywords: University of California, Santa Cruz history, University Library Administration Abstract: Allan J. [Lan] Dyson was appointed University Librarian at UC Santa Cruz's University Library in August 1979, and retired in July 2003. This oral history, conducted as part of the Regional History Project's University History Series, is a singular contribution to the documentation of twenty- four years of history, not only of UCSC's University Library, but also of a period of extensive technological and cultural transformations in academic librarianship in the United States. Supporting material: Dyson Full Audio Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. University of California, Santa Cruz University Library Allan J. Dyson: Managing the UCSC Library, 1979-2003 Interviewed and Edited by Irene Reti Santa Cruz, California 2006 All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Allan J. Dyson, dated July 10, 2006. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All the literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the University of California, Santa Cruz.