UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thestudentissue

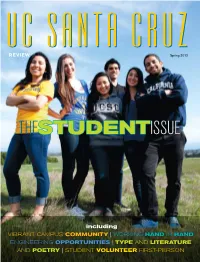

UC SANTA CRUZSpring 2013 UC SANTA CRUZREVIEW THESTUDENTISSUE including VIBRANT CAMPUS COMMUNITY | WORKING HAND IN HAND ENGINEERING OPPORTUNITIES | TYPE AND LITERATURE AND POETRY | STUDENT VOLUNTEER FIRST-PERSON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ Chancellor George Blumenthal Vice Chancellor, University Relations Donna Murphy UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW Spring 2013 photo: jim mackenzie Editor Gwen Jourdonnais Creative Director Lisa Nielsen Art Director/Designer Linda Knudson (Cowell ’76) From the Chancellor Associate Editor Dan White Cover Photo Carolyn Lagattuta They are smart and hardworking. The admitted Tenacious, imaginative, freshman class for fall 2012 had an average high Photography school GPA of nearly 3.8. Carolyn Lagattuta conscientious—and bright! Jim MacKenzie Our students are also whimsical, fun, creative, Elena Zhukova When I walk around campus, I’m gratified and and innovative—think hipster glasses and flowered inspired by UCSC students. I see students en- velvet Doc Martens—in addition to being tutors, Contributors gaged in the full range of academic and creative mentors, and volunteers. Amy Ettinger Guy Lasnier (Merrill ’78) pursuits, as well as extracurricular activities. This They are active—and we’re ready for them, with Scott Rappaport issue of Review celebrates our students. more than 100 student organizations, 14 men’s Tim Stephens Peggy Townsend Who are today’s students? and women’s NCAA intercollegiate teams, and a Dan White To give you an idea, consider our most recent wide variety of athletic clubs, intramural leagues, and rec programs. Produced by applicant pool. More than 46,000 prospective UC Santa Cruz undergraduates—the most ever—applied for admis- Banana Slugs revel in our broad academic offer- Communications sion to UCSC for the fall 2013 quarter. -

2002-03 Budget for Current Operations and Extramurally Funded Operations (Table)

2002 2003 Budget for Current Operations UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Office of the President November 2001 The President’s Message Just one year ago, California enjoyed near-record prosperity and an optimistic view of its future. Today the state faces a major economic slowdown and the unresolved menace of international terrorism. The world has suddenly become a much less certain place for individuals and institutions alike. Yet if there is one thing the current climate of uncertainty and risk makes dramatically clear, it is that research universities are indispensable to solving the nation’s most pressing problems, especially the threats of the new world in which we find ourselves. University of California engineers are already at work on technology that will make future high-rise buildings less vulnerable to terrorist attacks. Experts in bioterrorism are exploring ways to detect toxic substances and remove them from our air and water. Specialists in cybersecurity are investigating threats to communications networks that might develop in the next five to ten years and countermeasures to defend those networks. This is in addition to the daily discoveries and innovations that help make California, in the words of Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, “preeminent in transforming knowledge into economic value.” And this does not take into account the outstanding education we give our students across the UC System and the remarkable variety of public service we offer California’s citizens. Given the reality of the State’s fiscal situation, we will have difficult choices to make in the year ahead. But most economists believe that the major fiscal problems of the State are short-term in nature, a perspective that should guide our decision-making as we weigh priorities. -

UCSF Fact Sheet

About UCSF University of California, San Francisco is the leading university exclusively focused on health. Through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in care delivery, UCSF is leading revolutions in health worldwide. UCSF Health was one of the first U.S. hospitals to provide care for patients with COVID-19 and played a significant role in the public health response in collaboration with the City and State, as well as in research into testing, transmission prevention and care protocols and working in our communities throughout the pandemic. UCSF Chancellor Health Care Sam Hawgood, MBBS, a renowned Q UCSF Health is recognized worldwide researcher, professor, academic leader for its innovative, patient-centered care, and pediatrician, has been Chancellor informed by pioneering research and of UCSF since 2014. advanced technologies. Recognized for his strong leadership as UCSF Medical Center ranks among the top 10 hospitals nationwide dean of UCSF School of Medicine from for the care it provides and is among the leading medical centers 2009 to 2014 and brief tenure as interim across all 15 specialties ranked by U.S. News & World Report. It is Chancellor, Hawgood was selected renowned for innovative care in cancer, neurology and neurosurgery, after a national search as UCSF’s 10th cardiology and cardiac surgery, otolaryngology, transplant, chancellor. He reports to UC President .JDIBFM7%SBLF .% and ophthalmology, pulmonology, and urology, among others. UIFUC Board of Regents. With more than 1,700 clinical trials each year, UCSF Health is at Today, Hawgood, the Arthur and Toni Rembe Rock Distinguished the forefront in offering patients the latest therapies, led by clinician Professor at UCSF, oversees a UCSF enterprise, which # researchers who are committed to providing the most advanced care includes the top public recipient of research funds from the in their fields. -

Medical Centers Report

Attachment 5 Medical Centers Report 18/19 UC Health is committed to nothing less than the well-being of all Californians. As one of the nation’s largest academic health systems, we combine teaching, research and public service to provide high quality care to millions of patients each year and to drive the medical advances that save lives. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Medical Centers 18/19 Annual Financial Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Letter from the Executive Vice President Medical Centers 4 The University of California, Davis Medical Center 8 The University of California, Irvine Medical Center 12 The University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center 16 The University of California, San Diego Medical Center 20 The University of California, San Francisco Medical Center and Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland 26 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 52 Report of Independent Auditors Financial Statements, University of California Medical Centers 54 Statements of Net Position 56 Statements of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Net Position 58 Statements of Cash Flows 62 Notes to Financial Statements 110 Required Supplementary Information 116 University of California Regents and Officers 2 Letter from the Executive Vice President This is my last annual report letter as Executive Vice President • Our payor mix demonstrates our unwavering commitment of UC Health. to caring for all Californians regardless of ability to pay. Despite representing less than six percent of the acute After 50 years in Medicine and 11 years with the University care hospital beds in California, we are one of the largest of California, it is time for me to turn the reins of leadership for providers of inpatient services and hospital-based outpatient UC Health to another. -

Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society

Journal of Diversity in Higher Education © 2016 National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education 2016, Vol. 9, No. 3, 189–202 1938-8926/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000039 INTRODUCTION Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society Robert A. Rhoads University of California, Los Angeles This introductory article provides a historical overview of various student move- ments and forms of student activism from the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement to the present. Accordingly, the historical trajectory of student activism is framed in terms of 3 broad periods: the sixties, the postsixties, and the contem- porary context. The author pays particular attention to student organizing to address racial inequality as well as other forms of diversity. The article serves as an introduction to this special issue and includes a brief summary of the remainder of the issue’s content. Keywords: student activism, student movements, student organizing, social justice, campus-based inequality During the early 1990s, as a doctoral student campus, including in classrooms and residence in sociology and higher education, I began to halls. The students also participated in the 1993 systematically explore forms of activism and March on Washington for lesbian, gay, and direct action on the part of U.S. college stu- bisexual rights. I too joined the march and re- dents. My dissertation work focused on gay and corded many of the students’ experiences and bisexual males, including most notably their reflections, some of which are included in Com- coming out experiences and the subsequent en- ing Out in College. -

Phone Directory

Phone Directory MAIN PHONE NUMBERS UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay . (415)353-3000 UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion . .(415) 567-6600 UCSF Medical Center at Parnassus . (415)476-1000 LOCATION KEY GMB UCSF Ron Conway Family Gateway Medical Building WCH UCSF Betty Irene Moore Women’s Hospital and UCSF Bakar Cancer Hospital BCH UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital DEPARTMENT . LOCATION . PHONE* Admitting - Adult . WCH 1.476-1099 Blood Bank . .GMB 2.476-1404 Case Management - Adult (Main offi ce) . 514-3742 Case Management - Children’s (Main offi ce) . .353-2278 Central Patient Placement - Adult . .353-1937 Child Life Services (Main offi ce) . BCH 5 & 6 . .353-1203 Child Life Manager . .353-8500 Marie Wattis School Program . BCH 6 . 353-1310 Child Life Playground . BCH 5 . .353-1221 Center for Families . BCH 6 .353-1410 Clinical Lab . GMB2.353-1667 Blood Gas . .514-2146 Gift Shop . .BCH1476-1150 Infection Control . .353-4343 Interpreting Services . .GMB 1 .353-2690 IP3 . .WCH4353-1328 Information Desk - Adult . WCH 1 . .476-1540 Neurodiagnostics . BCH 5 .514-4177 Nursing Administration . BCH 1 . .476-1592 Nutrition and Food Services . WCH 1 . .476-1085 Room Service . .353-1111 *All phone numbers are in area code 415 DEPARTMENT ......................... LOCATION .... PHONE* Occupational Health & Safety . BCH 1 . 885-7580 Needlestick Exposure 24 Hour Number . .353-STIC (7842) Parking and Transportation . 476-1511 Pathology . GMB 2 . 353-1613 Patient Relations . BCH 1 . 353-1936 Patient Access - Children’s . BCH 1 . 353-1611 Pediatric Echocardiography . GMB 6 . 476-3774 Pediatric Pulmonary Function Lab . GMB 6 . 476-3774 Pediatric Stress Lab/EKG . -

The Commune Movement During the 1960S and the 1970S in Britain, Denmark and The

The Commune Movement during the 1960s and the 1970s in Britain, Denmark and the United States Sangdon Lee Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2016 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ⓒ 2016 The University of Leeds and Sangdon Lee The right of Sangdon Lee to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ii Abstract The communal revival that began in the mid-1960s developed into a new mode of activism, ‘communal activism’ or the ‘commune movement’, forming its own politics, lifestyle and ideology. Communal activism spread and flourished until the mid-1970s in many parts of the world. To analyse this global phenomenon, this thesis explores the similarities and differences between the commune movements of Denmark, UK and the US. By examining the motivations for the communal revival, links with 1960s radicalism, communes’ praxis and outward-facing activities, and the crisis within the commune movement and responses to it, this thesis places communal activism within the context of wider social movements for social change. Challenging existing interpretations which have understood the communal revival as an alternative living experiment to the nuclear family, or as a smaller part of the counter-culture, this thesis argues that the commune participants created varied and new experiments for a total revolution against the prevailing social order and its dominant values and institutions, including the patriarchal family and capitalism. -

Rebel Girls This Page Intentionally Left Blank Rebel Girls

Rebel Girls This page intentionally left blank Rebel Girls Youth Activism and Social Change across the Americas Jessica K. Taft a New York University Press New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2011 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taft, Jessica K. Rebel girls : youth activism and social change across the Americas / Jessica K. Taft. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8147–8324–5 (cl : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–8147–8325–2 (pb : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–8147–8337–5 (ebook) 1. Teenage girls—Political activity—America. 2. Youth—Political activity—America. 3. Social action—America. I. Title. HQ799.2.P6T35 2010 305.235’2097—dc22 2010024128 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books. Manufactured in the United States of America c 10987654321 p 10987654321 For all the girls fighting the good fight in their schools and communities. This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction: Growing Up and Rising Up 1 Part 1: Building the Activist Identity 2 We Are Not Ophelia: Empowerment and Activist Identities 23 3 We Are Not the Future: Claiming Youth Authority 47 4 We Are Not Girls: Escaping and Defining Girlhood 71 Part 2: Making Change Happen 5 The Street Is Our Classroom: A Politics of Learning 99 6 Join the Party: A Politics of Participation 123 7 We’ve Got Spirit: A Politics of Hope 151 8 Conclusion: Still Rising 177 Methodological Appendix 193 Demographic Tables 201 Notes 205 Index 229 About the Author 241 | vii This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments Several amazing political and intellectual communities have sus- tained and inspired me throughout the process of research and writing this book. -

Student Activism As Labor

"A Student Should Have the Privilege of Just Being a Student": Student Activism as Labor Chris Linder, Stephen John Quaye, Alex C. Lange, Ricky Ericka Roberts, Marvette C. Lacy, Wilson Kwamogi Okello The Review of Higher Education, Volume 42, Supplement 2019, pp. 37-62 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0044 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/724910 Access provided at 5 Jul 2019 18:36 GMT from University of Utah LINDER ET. AL. / Student Activism as Labor 37 The Review of Higher Education Special Issue 2019, Volume 42, Supplement, pp. 37–62 Copyright © 2019 Association for the Study of Higher Education All Rights Reserved (ISSN 0162–5748) “A Student Should Have the Privilege of Just Being a Student”: Student Activism as Labor Chris Linder, Stephen John Quaye, Alex C. Lange, Ricky Ericka Roberts, Marvette C. Lacy, and Wilson Kwamogi Okello Chris Linder (she/her/hers) is an Assistant Professor of Higher Education at the University of Utah, where she studies sexual violence and student activism through a power-conscious, historical lens. Chris identi- fies as a queer, white cisgender woman from a working-class background and earned a PhD in Higher Education and Student Affairs Leadership from the University of Northern Colorado. Stephen John Quaye is associate professor in the Student Affairs in Higher Education Program at Miami University and Past President of ACPA: College Student Educators International. His research focuses on strategies for engaging in difficult dialogues; student and scholar activism; and healing from racial battle fatigue. -

Navigating University Bureaucracy for Social Change: Transgender & Gender-Nonconforming Students Kate Hoffman

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College 5-5-2017 Navigating University Bureaucracy for Social Change: Transgender & Gender-Nonconforming Students Kate Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hoffman, Kate, "Navigating University Bureaucracy for Social Change: Transgender & Gender-Nonconforming Students" (2017). Senior Theses. 165. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/165 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Navigating University Bureaucracy for Social Change: Transgender & Gender-Nonconforming Students By: Kate Hoffman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors from the South Carolina Honors College University of South Carolina Spring 2017 Approved by: ______________________________________________________ Laura C. Hein, Ph.D, RN, FAAN Director of Thesis ______________________________________________________ John Dozier, Ed.D Second Reader Hoffman 1 Introduction 2 Barriers that TGNC Students Face at the University of South Carolina 6 Housing 7 University Identification and Official Documentation 9 Restrooms 10 Student Health Services 12 Classroom and Campus Environment 14 University Police & Behavioral Intervention 15 Available -

Cumulative Bio-Bibliography University of California, Santa Cruz June 2020

Cumulative Bio-Bibliography University of California, Santa Cruz June 2020 Puragra Guhathakurta Astronomer/Professor University of California Observatories/University of California, Santa Cruz ACADEMIC HISTORY 1980–1983 B.Sc. in Physics (Honours), Chemistry, and Mathematics, St. Xavier’s College, University of Calcutta 1984–1985 M.Sc. in Physics, University of Calcutta Science College; transferred to Princeton University after first year of two-year program 1985–1987 M.A. in Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University 1987–1989 Ph.D. in Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University POSITIONS HELD 1989–1992 Member, Institute for Advanced Study, School of Natural Sciences 1992–1994 Hubble Fellow, Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University 1994 Assistant Astronomer, Space Telescope Science Institute (UPD) 1994–1998 Assistant Astronomer/Assistant Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 1998–2002 Associate Astronomer/Associate Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 2002–2003 Herzberg Fellow, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council of Canada, Victoria, BC, Canada 2002– Astronomer/Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 2009– Faculty Director, Science Internship Program, University of California, Santa Cruz 2012–2018 Adjunct Faculty, Science Department, Castilleja School, Palo Alto, CA 2015 Visiting Faculty, Google Headquarters, Mountain View, CA 2015– Co-founder, Global SPHERE (STEM Programs for High-schoolers Engaging in Research -

Rick Laubscher: Forty Years of Giving Back to San Francisco, from KRON to Market Street Railway

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Rick Laubscher Rick Laubscher: Forty Years of Giving Back to San Francisco, From KRON to Market Street Railway Interviews conducted by Todd Holmes in 2016 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Rick Laubscher dated March 30, 2017 The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.