An Exploratory Study of Online Community Building in the Youth Climate Change Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani Is an Engineer Who’S Been Thinking About Energy for More Than 35 Years

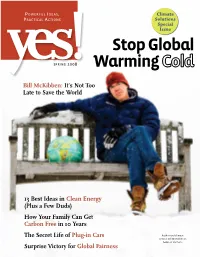

Powerful Ideas, Climate PractIcal actIons Solutions Special Issue Stop Global yes!sPrIng 2008 Warming Bill McKibben: It’s Not Too Late to Save the World 13 Best Ideas in Clean Energy (Plus a Few Duds) How Your Family Can Get Carbon Free in 10 Years The Secret Life of Plug-in Cars Author and climate activist Bill McKibben at home in Vermont Surprise Victory for Global Fairness “One way or another, the choice will be made by our generation, but it will affect life on earth for all generations to come.” Lester Brown , Earth Policy Institute Tsewang Norbu was selected by his Himalayan village to be trained at the Barefoot College of Tilonia, India, in the installation and repair of solar photovoltaic units. All solar units were brought to the village across the 18,400- foot Khardungla Pass by yak and on villagers’ backs. photo by barefoot photographers of tilonia. copyright 2008 barefoot college, tilonia, rajastan, india, barefootcollege.org yesm a g a z i! n e www.yesmagazine.org Reprinted from the “Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani is an engineer who’s been thinking about energy for more than 35 years. When he heard a presentation ISSUE 45 claiming we needed to go fossil-carbon free by 2050, he didn’t YES! THEME GUIDE think it could be done. X years of research later, he’s changed his mind. His book, Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free: A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy, tells exactly how it can be done. Here’s how Makhijani sees the energy supply changing for buildings, CLIMATE SOLUTIONStransportation and electricity. -

2019 (November 2018 – October 2019)

QUAKER EARTHCARE WITNESS ANNUAL REPORT November 2018 - October 2019 Affirming our essential unity with nature Above: Friends visit Jim and Kathy Kessler’s restored native plant habitat during the Friends General Conference Gathering in Iowa. OUR WORK THIS YEAR Quaker Earthcare Witness has grown over the last 32 years out of a deepening sense of QUAKER ACTIVISM & spiritual connection with the natural world. From this has come an urgency to work on the critical EDUCATION issues of our times, including climate and environmental justice. This year we are excited to see that more people This summer we sponsored the QEW Earthcare Center are mobilizing around the eco-crises than ever before, at the Friends General Conference annual gathering, both within and beyond the Religious Society of Friends. including scheduling and hosting presentations every afternoon, showcasing what Friends are doing regarding With your help, Quaker Earthcare Witness is Earthcare, displaying resources to share, and giving responding to the growing need for inspiration talks. We offered presentations on climate justice, and support for Friends and Meetings. indigenous concerns, eco-spirituality, activism and hope, permaculture, and children’s education. We also QEW is the largest network of Friends working on sponsored a field trip to a restored prairie (thanks to Jim Earthcare today. We work to inspire spirit-led action Kessler, QEW Steering Committee member, who planned toward ecological sustainability and environmental the trip and restored, along with his wife Kathy, this plot justice. We provide inspiration and resources to Friends of Iowa prairie). throughout North America by distributing information in our newsletter, BeFriending Creation, on our website Our General Secretary, Communications Coordinator, quakerearthcare.org and through social media. -

Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society

Journal of Diversity in Higher Education © 2016 National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education 2016, Vol. 9, No. 3, 189–202 1938-8926/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000039 INTRODUCTION Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society Robert A. Rhoads University of California, Los Angeles This introductory article provides a historical overview of various student move- ments and forms of student activism from the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement to the present. Accordingly, the historical trajectory of student activism is framed in terms of 3 broad periods: the sixties, the postsixties, and the contem- porary context. The author pays particular attention to student organizing to address racial inequality as well as other forms of diversity. The article serves as an introduction to this special issue and includes a brief summary of the remainder of the issue’s content. Keywords: student activism, student movements, student organizing, social justice, campus-based inequality During the early 1990s, as a doctoral student campus, including in classrooms and residence in sociology and higher education, I began to halls. The students also participated in the 1993 systematically explore forms of activism and March on Washington for lesbian, gay, and direct action on the part of U.S. college stu- bisexual rights. I too joined the march and re- dents. My dissertation work focused on gay and corded many of the students’ experiences and bisexual males, including most notably their reflections, some of which are included in Com- coming out experiences and the subsequent en- ing Out in College. -

Racial Diversity in the U.S. Climate Movement

Diversity and the Environment Webinar Series Presented by: Racial Diversity in the U.S. Climate Movement TUESDAY, MARCH 17, 2020 12:00 PM-1:00 PM ET Webinar Logistics Everyone should be connected via Audio Broadcast upon entering the webinar. You do not need to call in & you are automatically muted The presentation will be recorded and posted to the Antioch CCPCR web site within one week Please submit any questions you have for the presenter in the Q& A section If you are having trouble with any aspect of the broadcast, use the Chat section to message the Host directly Moderator Abi Abrash Walton, Ph.D. Faculty, Department of Environmental Studies Director, Master's Programs Director, Advocacy for Social Justice & Sustainability Master's Concentration, Co-Director, Center for Climate Preparedness & Community Resilience Director, Conservation Psychology Institute Antioch University New England Presenter Clara Fang Higher Education Outreach Coordinator Citizens’ Climate Lobby PhD Environmental Studies Antioch University Master of Environmental Management Yale University Racial Diversity in the U.S. Climate Movement Clara Fang Antioch University March 17, 2020 What we are going to cover Why and what How are we Building a just is diversity? doing? and inclusive climate movmeent 1 2 3 t Why diversity? Nature thrives on diversity POC Voters are Increasingly Determining Outcomes of Elections Image from: https://www.lwvcga.org/how-safe-are-georgias-elections/ A man puts his baby on top of his car as he and a woman abandon their car in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. REUTERS/Rick Wilking People of color are usually the hardest hit from the effects of climate change. -

Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth Is the Most Important Book of Our Time

CHOOSING EARTH Humanity’s Great Transition to a Mature Planetary Civilization Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth is the most important book of our time. To read and dwell within it is an awakening experience that can activate both an ecological and spiritual revolution.” —Jean Houston, PhD, Chancellor of Meridian University, philosopher, author of The Possible Human, Jump Time, Life Force and many more. “A truly essential book for our time — from one of the greatest and deepest thinkers of our time. Whoever is concerned to create a better future for the human family must read this book — and take to heart the wisdom it offers.” —Ervin Laszlo is evolutionary systems philosopher, author of more than one hundred books including The Intelligence of the Cosmos and Global Shift. “This may be the perfect moment for so prophetic a voice to be heard. Sobered by the pandemic, we are recognizing both the fragility of our political arrangements and the power of our mutual belonging. As Elgin knows, we already possess the essential ingredient —our capacity to choose.” —Joanna Macy, author of Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We're in Without Going Crazy, is root teacher of the Work That Reconnects and celebrated in A Wild Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time. “Duane Elgin has thought hard — and meditated long — about what it will take for humanity to evolve past our looming ecological bottleneck toward a future worth building. There is wisdom in these pages to light the way through our dark and troubled times.” —Richard Heinberg is one of the world’s foremost advocates for a shift away from reliance on fossil fuels; author of Our Renewable Future, Peak Everything, and The End of Growth. -

Actes 2020 Assemblée Des Femmes

28e UNIVERSITÉ D’AUTOMNE de L’ASSEMBLÉE DES FEMMES « Il suffira d’une crise…L’urgence féministe » 10 et 11 octobre 2020 En visio-conférence 1 La 28e Université d’automne de L’Assemblée des Femmes s’est tenue en « distanciel » les 10 et 11 octobre 2020, selon un mode de fonctionnement imposé par la pandémie de COVID-19 en cette année 2020. La conception et la préparation de ces journées, ainsi que la réalisation de ces Actes, ont été assurées par le bureau de l’Assemblée des Femmes. Les travaux de l’Université-2020 de l’ADF ont bénéficié de la mobilisation de « l’équipe technique » - Yseline Fourtic-Dutarde, Sara Jubault et Marion Nabier -, et du soutien logistique de « l’équipe de La Rochelle », Corinne Cap et Sylvie-Olympe Moreau, administratrices de l’ADF. L’ADF a reçu le soutien de la Région Nouvelle Aquitaine et d’Élisabeth Richard, ENGIE N° ISBN : 978-2-9565389-1-2 2 ACTES DE LA 28e UNIVERSITÉ DE L’ASSEMBLÉE DES FEMMES 10 et 11 octobre 2020 En visio-conférence « Il suffira d’une crise… L’urgence féministe » TABLE DES MATIÈRES Samedi 10 octobre 2020 Ouverture de l’Université d’automne- 2020, p. 5 à 8. - Laurence ROSSIGNOL, p. 5. - Maryline SIMONÉ, p.6. Table ronde I « Féminisme + écologie = écoféminisme ? » p. 9 à 39. Présentation et modération, Jacqueline DEVIER, p.9. 1è partie, p. 12 à 25. - Monique DENTAL, p.12. - Marie TOUSSAINT, p.18. Débat avec la salle virtuelle p. 23 à 25 2è partie, p. 25 à 39. - Delphine BATHO, p. -

The Commune Movement During the 1960S and the 1970S in Britain, Denmark and The

The Commune Movement during the 1960s and the 1970s in Britain, Denmark and the United States Sangdon Lee Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2016 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ⓒ 2016 The University of Leeds and Sangdon Lee The right of Sangdon Lee to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ii Abstract The communal revival that began in the mid-1960s developed into a new mode of activism, ‘communal activism’ or the ‘commune movement’, forming its own politics, lifestyle and ideology. Communal activism spread and flourished until the mid-1970s in many parts of the world. To analyse this global phenomenon, this thesis explores the similarities and differences between the commune movements of Denmark, UK and the US. By examining the motivations for the communal revival, links with 1960s radicalism, communes’ praxis and outward-facing activities, and the crisis within the commune movement and responses to it, this thesis places communal activism within the context of wider social movements for social change. Challenging existing interpretations which have understood the communal revival as an alternative living experiment to the nuclear family, or as a smaller part of the counter-culture, this thesis argues that the commune participants created varied and new experiments for a total revolution against the prevailing social order and its dominant values and institutions, including the patriarchal family and capitalism. -

Arab Youth Climate Movement

+ Arab Youth Climate Movement UNEP – ROWA Regional Stakeholders Meeting + From Rio to Doha + Rio+20 + UNEP’s Role in Civil Society engagement Build on the Rio+20 outcomes para. 88h and 99 in particular, and to make sure that we see progress: The need for an international convention on procedural rights, as well as regional conventions with compliance mechanisms. The need for UNEP to show leadership when implementing its new mandate under para 88h and to promote mechanisms for a strengthening of public participation in International Environmental Governance, not only within its own processes but also across the whole IEG (as it has done in the past with its Bali Guidelines). + + Sept 2012 - Birth of the Arab Youth Climate Movement (AYCM) + + Arab Youth Climate Movement The Arab Youth Climate Movement (AYCM) is an independent body that works to create a generation-wide movement across the Middle East & North Africa to solve the climate crisis, and to assess and support the establishment of legally binding agreements to deal with climate change issue within international negotiations. The AYCM has a simple vision – we want to be able to enjoy a stable climate similar to that which our parents and grandparents enjoyed. + COP18 + Day of Action – Key Messages Climate change is a threat to all life on the planet. Unfortunately, the Arab countries have so far been the only region that is ignoring the threat of climate change. Arab leaders must fulfill their responsibilities towards future generations, by working constructively and strongly on the national and international level to achieve greenhouse gas emission reduction in the region and globally. -

C H a P T E R Iv

CHAPTER IV Moving forward: youth taking action and making a difference The combined acumen and involvement of all individuals, from regular citizens to scientific experts, will be needed as the world moves forward in implementing climate change miti- gation and adaptation measures and promot- ing sustainable development. Young people must be prepared to play a key role within this context, as they are the ones who will live to R IV experience the long-term impact of today’s crucial decisions. TE The present chapter focuses on the partici- pation of young people in addressing climate change. It begins with a review of the various mechanisms for youth involvement in environ- HAP mental advocacy within the United Nations C system. A framework comprising progressive levels of participation is then presented, and concrete examples are provided of youth in- volvement in climate change efforts around the globe at each of these levels. The role of youth organizations and obstacles to partici- pation are also examined. PROMOTING YOUTH ture. In addition to their intellectual contribution and their ability to mobilize support, they bring parTICipaTION WITHIN unique perspectives that need to be taken into account” (United Nations, 1995, para. 104). THE UNITED NATIONS The United Nations has long recognized the Box IV.1 importance of youth participation in decision- making and global policy development. Envi- The World Programme of ronmental issues have been assigned priority in Action for Youth on the recent decades, and a number of mechanisms importance of participation have been established within the system that The World Programme of Action for enables youth representatives to contribute to Youth recognizes that the active en- climate change deliberations. -

Rebel Girls This Page Intentionally Left Blank Rebel Girls

Rebel Girls This page intentionally left blank Rebel Girls Youth Activism and Social Change across the Americas Jessica K. Taft a New York University Press New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2011 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taft, Jessica K. Rebel girls : youth activism and social change across the Americas / Jessica K. Taft. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8147–8324–5 (cl : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–8147–8325–2 (pb : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–8147–8337–5 (ebook) 1. Teenage girls—Political activity—America. 2. Youth—Political activity—America. 3. Social action—America. I. Title. HQ799.2.P6T35 2010 305.235’2097—dc22 2010024128 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books. Manufactured in the United States of America c 10987654321 p 10987654321 For all the girls fighting the good fight in their schools and communities. This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction: Growing Up and Rising Up 1 Part 1: Building the Activist Identity 2 We Are Not Ophelia: Empowerment and Activist Identities 23 3 We Are Not the Future: Claiming Youth Authority 47 4 We Are Not Girls: Escaping and Defining Girlhood 71 Part 2: Making Change Happen 5 The Street Is Our Classroom: A Politics of Learning 99 6 Join the Party: A Politics of Participation 123 7 We’ve Got Spirit: A Politics of Hope 151 8 Conclusion: Still Rising 177 Methodological Appendix 193 Demographic Tables 201 Notes 205 Index 229 About the Author 241 | vii This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments Several amazing political and intellectual communities have sus- tained and inspired me throughout the process of research and writing this book. -

Student Activism As Labor

"A Student Should Have the Privilege of Just Being a Student": Student Activism as Labor Chris Linder, Stephen John Quaye, Alex C. Lange, Ricky Ericka Roberts, Marvette C. Lacy, Wilson Kwamogi Okello The Review of Higher Education, Volume 42, Supplement 2019, pp. 37-62 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0044 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/724910 Access provided at 5 Jul 2019 18:36 GMT from University of Utah LINDER ET. AL. / Student Activism as Labor 37 The Review of Higher Education Special Issue 2019, Volume 42, Supplement, pp. 37–62 Copyright © 2019 Association for the Study of Higher Education All Rights Reserved (ISSN 0162–5748) “A Student Should Have the Privilege of Just Being a Student”: Student Activism as Labor Chris Linder, Stephen John Quaye, Alex C. Lange, Ricky Ericka Roberts, Marvette C. Lacy, and Wilson Kwamogi Okello Chris Linder (she/her/hers) is an Assistant Professor of Higher Education at the University of Utah, where she studies sexual violence and student activism through a power-conscious, historical lens. Chris identi- fies as a queer, white cisgender woman from a working-class background and earned a PhD in Higher Education and Student Affairs Leadership from the University of Northern Colorado. Stephen John Quaye is associate professor in the Student Affairs in Higher Education Program at Miami University and Past President of ACPA: College Student Educators International. His research focuses on strategies for engaging in difficult dialogues; student and scholar activism; and healing from racial battle fatigue. -

Climate Justice Club Presents a Factbook on the Intersection of Social Justice and Environmental and Climate Justice

The College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University’s Climate Justice Club presents a Factbook on the intersection of social justice and environmental and climate justice. During the summer of 2020, we released the Factbook Unlearning Racist Behaviors in the Climate Activist World, which addresses the intersection of climate justice and environmental racism. The purpose of this factbook is to encourage our audience to utilize the sources in an effort to educate themselves about the disproportionate impact polluting industries have on communities of color. Social Justice in the Environmental Movement: A Factbook to Explore and Learn About the Intersection of Social Justice & Environmental and Climate Justice expands on our past factbook by not only considering how our club’s mission overlaps with racial justice, but with social justice as a whole. Please visit NAACP’s website to learn more about environmental and climate justice. Climate Justice Club encourages you to read through these resources to understand/learn why there is no climate justice without social justice. Please view the Table of Contents to explore the various media presented throughout the Factbook; there are resources for everyone! We believe it is pertinent that we continue educating ourselves and turn this learning into collective action. Share with us the information that stuck out most to you, and promote it on social media! We would like to credit the organization/platform Intersectional Environmentalist for providing some of the resources found throughout the Factbook. Authored by Maggie Morin With Support by Con Brady, Melissa Burrell, Valerie Doze, Tamia Francois, & Carolyn Rowley In Collaboration with Saint John’s Outdoor University 1 Table of Contents Items below are hyperlinked for your convenience.