UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thestudentissue

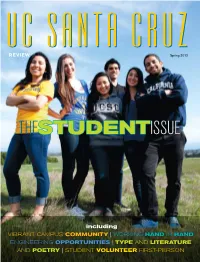

UC SANTA CRUZSpring 2013 UC SANTA CRUZREVIEW THESTUDENTISSUE including VIBRANT CAMPUS COMMUNITY | WORKING HAND IN HAND ENGINEERING OPPORTUNITIES | TYPE AND LITERATURE AND POETRY | STUDENT VOLUNTEER FIRST-PERSON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ Chancellor George Blumenthal Vice Chancellor, University Relations Donna Murphy UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW Spring 2013 photo: jim mackenzie Editor Gwen Jourdonnais Creative Director Lisa Nielsen Art Director/Designer Linda Knudson (Cowell ’76) From the Chancellor Associate Editor Dan White Cover Photo Carolyn Lagattuta They are smart and hardworking. The admitted Tenacious, imaginative, freshman class for fall 2012 had an average high Photography school GPA of nearly 3.8. Carolyn Lagattuta conscientious—and bright! Jim MacKenzie Our students are also whimsical, fun, creative, Elena Zhukova When I walk around campus, I’m gratified and and innovative—think hipster glasses and flowered inspired by UCSC students. I see students en- velvet Doc Martens—in addition to being tutors, Contributors gaged in the full range of academic and creative mentors, and volunteers. Amy Ettinger Guy Lasnier (Merrill ’78) pursuits, as well as extracurricular activities. This They are active—and we’re ready for them, with Scott Rappaport issue of Review celebrates our students. more than 100 student organizations, 14 men’s Tim Stephens Peggy Townsend Who are today’s students? and women’s NCAA intercollegiate teams, and a Dan White To give you an idea, consider our most recent wide variety of athletic clubs, intramural leagues, and rec programs. Produced by applicant pool. More than 46,000 prospective UC Santa Cruz undergraduates—the most ever—applied for admis- Banana Slugs revel in our broad academic offer- Communications sion to UCSC for the fall 2013 quarter. -

Franklin D. Murphy Papers, 1948-1994

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8g5008hv No online items Finding Aid for the Franklin D. Murphy Papers, 1948-1994 Processed by Lilace Hatayama, 1998; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Franklin D. 363 1 Murphy Papers, 1948-1994 Finding Aid for the Franklin D. Murphy Papers, 1948-1994 Collection number: 363 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff, 1994 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, August 2002 © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Franklin D. Murphy Papers, Date (inclusive): 1948-1994 Collection number: 363 Creator: Murphy, Franklin D., 1916- Extent: 79 boxes (39.5 linear ft.) 21 oversize boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Franklin David Murphy (1916-1994) was the Chancellor at the University of Kansas (1951-60), Chancellor at UCLA (1960-68), Chairman of the Board and CEO (1968) and Chairman of the Executive Committee (1981-86) of the Times Mirror Company. -

BOG Meeting Agenda November 7 2019

Photos: (clockwise from left) Feather River College, San Diego Miramar College, Los Angeles Pierce College Meeting Agenda Monday, November 18, 2019 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM* Chancellor’s Office 1102 Q Street, 6th Floor Sacramento, CA 95811 *All times are approximate and subject to change. Order of items is subject to change. OFFICERS OF THE BOARD Tom Epstein Pamela Haynes President Vice President CHANCELLOR’S OFFICE Eloy Ortiz Oakley Chancellor MISSION STATEMENT “Empowering Community Colleges Through Leadership, Advocacy and Support.” VISION FOR SUCCESS GOALS 1. Increase by at least 20 percent the number of California Community Colleges (CCC) students annually who acquire associates degrees, credentials, certificates, or specific skill sets that prepare them for an in-demand job. 2. Increase by 35 percent the number of CCC students transferring annually to a University of California or California State University. 3. Decrease the average number of units accumulated by CCC students earning associate’s degrees, from approximately 87 total units (the most recent system-wide average) to 79 total units—the average among the quintile of colleges showing the strongest performance on this measure. 4. Increase the percent of exiting Career Technical Education (CTE) students who report being employed in their field of study, from the most recent statewide average of 60 percent to an improved rate of 69 percent—the average among the quintile of colleges showing the strongest performance on this measure. 5. Reduce equity gaps across all of the above measures through faster improvements among traditionally underrepresented student groups, with the goal of cutting achievement gaps by 40 percent within five years and fully closing those achievement gaps within ten years. -

Legislators of California

The Legislators of California March 2011 Compiled by Alexander C. Vassar Dedicated to Jane Vassar For everything With Special Thanks To: Shane Meyers, Webmaster of JoinCalifornia.com For a friendship, a website, and a decade of trouble-shooting. Senator Robert D. Dutton, Senate Minority Leader Greg Maw, Senate Republican Policy Director For providing gainful employment that I enjoy. Gregory P. Schmidt, Secretary of the Senate Bernadette McNulty, Chief Assistant Secretary of the Senate Holly Hummelt , Senate Amending Clerk Zach Twilla, Senate Reading Clerk For an orderly house and the lists that made this book possible. E. Dotson Wilson, Assembly Chief Clerk Brian S. Ebbert, Assembly Assistant Chief Clerk Timothy Morland, Assembly Reading Clerk For excellent ideas, intriguing questions, and guidance. Jessica Billingsley, Senate Republican Floor Manager For extraordinary patience with research projects that never end. Richard Paul, Senate Republican Policy Consultant For hospitality and good friendship. Wade Teasdale, Senate Republican Policy Consultant For understanding the importance of Bradley and Dilworth. A Note from the Author An important thing to keep in mind as you read this book is that there is information missing. In the first two decades that California’s legislature existed, we had more individuals serve as legislators than we have in the last 90 years.1 Add to the massive turnover the fact that no official biographies were kept during this time and that the state capitol moved seven times during those twenty years, and you have a recipe for missing information. As an example, we only know the birthplace for about 63% of the legislators. In spite of my best efforts, there are still hundreds of legislators about whom we know almost nothing. -

Oral History Program

CALIFORNIA STATE ARCHIVES STATE GOVERNMENT ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW with ELIZABETH G. HILL PROGRAM ANALYST, LEGISLATIVE ANALYST'S OFFICE, 1976-1979 PRINCIPAL PROGRAM ANALYST, LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE, 1979-1986 CALIFORNIA LEGISLATIVE ANALYST, LEGISLATIVE ANALYST'S OFFICE, 1986-2009 July 30, August 11, 28 & September 17, 24, 2015 BY CHRISTOPHER J. CASTANEDA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO TABLE OF CONTENTS INTERVIEW HISTORY ..................................................................................................... i BIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY ......................................................................................... ii SESSION 1, July 30, 2015. ..................................................................................................1 Childhood and family in Modesto, California – growing up in the California Central Valley – early interest in basketball – involvement with 4-H Club and Junior Leader Program – wins 8th grade speech competition – speech and debate contests – involvement in student government: student body secretary and student body president – interest in American Field Service – intern for Clare Berryhill campaign (State Assembly) – admitted to Stanford University – Human Biology major – one year abroad in Umea, Sweden through AFS – discussion of the experience in Sweden – returns from Sweden on the day of the U.S. moon landing – attends Stanford – internship at CalTrans – meets Larry Hill – attends Graduate School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley -

Cumulative Bio-Bibliography University of California, Santa Cruz June 2020

Cumulative Bio-Bibliography University of California, Santa Cruz June 2020 Puragra Guhathakurta Astronomer/Professor University of California Observatories/University of California, Santa Cruz ACADEMIC HISTORY 1980–1983 B.Sc. in Physics (Honours), Chemistry, and Mathematics, St. Xavier’s College, University of Calcutta 1984–1985 M.Sc. in Physics, University of Calcutta Science College; transferred to Princeton University after first year of two-year program 1985–1987 M.A. in Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University 1987–1989 Ph.D. in Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University POSITIONS HELD 1989–1992 Member, Institute for Advanced Study, School of Natural Sciences 1992–1994 Hubble Fellow, Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University 1994 Assistant Astronomer, Space Telescope Science Institute (UPD) 1994–1998 Assistant Astronomer/Assistant Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 1998–2002 Associate Astronomer/Associate Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 2002–2003 Herzberg Fellow, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council of Canada, Victoria, BC, Canada 2002– Astronomer/Professor, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz 2009– Faculty Director, Science Internship Program, University of California, Santa Cruz 2012–2018 Adjunct Faculty, Science Department, Castilleja School, Palo Alto, CA 2015 Visiting Faculty, Google Headquarters, Mountain View, CA 2015– Co-founder, Global SPHERE (STEM Programs for High-schoolers Engaging in Research -

Rick Laubscher: Forty Years of Giving Back to San Francisco, from KRON to Market Street Railway

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Rick Laubscher Rick Laubscher: Forty Years of Giving Back to San Francisco, From KRON to Market Street Railway Interviews conducted by Todd Holmes in 2016 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Rick Laubscher dated March 30, 2017 The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Oral History Interview with Hon. Alfred H. Song

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with HON. ALFRED H. SONG Deputy Attorney General of California, 1984 - present Member of the California State Senate, 1966-1978 Member of the California State Assembly, 1962-1966 August 18-19, 1986 Sacramento, California By Raphael J. Sonenshein California State University, Fullerton ~TRICTIONSONTIllSThITERvrnW None LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATION This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or the Oral History Program, History Department, California State University, Fullerton. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 1020 0 Street, Room 130 Sacramento, CA 95814 or Oral History Program History Department California State University, Fullerton Fullerton, CA 92634 The request should include identification of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Alfred H. Song, Oral History Interview, Conducted 1986 by Raphael J. Sonenshein, Oral History Program, History Department, California State University, Fullerton, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. Information (916) 445-4293 California State Archives March Fong Eu Research Room (916) 445-4293 10200 Street, Room 130 Exhibit Hall (916) 445-4293 Secretary of State Legislative Bill Service (916) 445-2832 -

Electromagnetics00whinrich.Pdf

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California College of Engineering Oral History Series John R. Whinnery RESEARCHER AND EDUCATOR IN ELECTROMAGNETICS, MICROWAVES, AND OPTOELECTRONICS, 1935-1995; DEAN OF THE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, UC BERKELEY, 1959-1963 With an Introduction by Donald 0. Pederson Interviews Conducted by Ann Lage in 1994 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and John R. Whinnery dated February 9, 1994. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title From Complex Organisms to a Complex Organization: An Oral History with UCSC Chancellor M.R.C. Greenwood, 1996-2004 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9hv2j5t9 Authors Reti, Irene H. Greenwood, M.R.C. Publication Date 2014-04-03 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Complex Organisms to a Complex Organization: An Oral History with UCSC Chancellor M.R.C. Greenwood, 1996-2004 Interviewed by Randall Jarrell and Irene Reti Edited by Irene Reti Santa Cruz University of California, Santa Cruz University Library 2014 This oral history is covered by a copyright agreement between M.R.C. Greenwood and the Regents of the University of California dated March 7, 2014. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the University Library’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the University Librarian and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. For permission contact: Irene Reti [email protected] or Regional History Project, McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA, 95064. Phone: 831-459-2847 Table of Contents Interview History 1 Associate Director for Science in the White House 6 Arriving at the University of California, Santa Cruz 21 Meeting UCSC Faculty and Staff 31 Changing UCSC’s Image 34 Relations -

Download William Morrow's Research

Students Speak Up: Perspectives of Free Speech Among Student Leaders in the University of California System STUDENTS SPEAK UP Perspectives of Free Speech Among Student Leaders in the University of California System by William MacKinnon Morrow | Fellow, University of California National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement The motto of the University of California, Berkeley is fiat of a mob of masked rioters surrounding an open flame lux, or “let there be light.” Over the past century and a half, on Sproul Plaza, as juxtaposed with the famous image of this motto has come to embody the spirit of Berkeley (and Mario Savio galvanizing the Free Speech Movement on the University of California, as a whole) as an institutional that same Sproul Plaza, came to symbolize this growing beacon for reasoned discourse, vibrant expression, and sentiment that our country’s universities were facing a free social inclusivity. However, as I looked out at the setting speech crisis. twilight looming ominously over Berkeley on February 1, 2017, I knew that while sparks were about to fly on There is indeed truth to this perception that the vibrancy campus that evening, this light that the University inspires of expression on university campuses has eroded in recent to the world would be dimmed. years, particularly for contrarian speech. And without a doubt, the events of February 1, 2017 at UC Berkeley That evening, the antagonistic and outlandish provocateur, will leave a lasting stain on the University’s legacy as an Milo Yiannopolous, was set to speak on Berkeley’s campus institution that welcomes and empowers civil discourse about his views on immigration in a thinly-veiled attempt among various viewpoints. -

Experimental Activism at UCSC, 1965-1970

1 Experimental Activism at UCSC, 1965-1970 By Robbie Stockman The 1960s shifted Americans' consciousness from complacency to dissatisfaction and revolt. The Civil Rights, Free Speech, Third World and antiwar movements together with the hippie subculture plunged the nation into chaotic liberation. In response to student concerns, University of California administrators created an ideal learning experiment at Santa Cruz. UC president Clark Kerr, UC Dean of Academic Planning Dean McHenry and University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) history professor Page Smith dedicated the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) to undergraduate education. Through a series of academic reforms and innovative techniques, UCSC administrators and faculty created an intellectually stimulating, communal university. Students at UCSC were compelled to create the culture of their university in this tumultuous time. Though UCSC student activism involved intellectual discussion and peaceful protest, they were ineffective at creating social change and as the campus developed, UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University (SFSU) began to control the direction of UCSC thought and action. UCSC: The Creation of an Aesthetic The dilemma at previous universities resulted from professors torn between their own research and educating undergraduate students. In the "publish or perish" world of higher education, professors focused mostly on their own research at the expense of student learning. UCLA history professor Page Smith considered such actions wasteful, considering