The Jesus Project: an Artistic Definition of the Sacred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue and Price List of Stereopticons

—. ; I, £3,v; and Descriptive , Illustrated ;w j CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST- t&fs — r~* yv4 • .'../-.it *.•:.< : .. 4^. ; • ’• • • wjv* r,.^ N •’«* - . of . - VJ r .. « 7 **: „ S ; \ 1 ’ ; «•»'•: V. .c; ^ . \sK? *• .* Stereopticons . * ' «». .. • ” J- r . .. itzsg' Lantern Slides 1 -f ~ Accessories for Projection Stereopticon and Film Exchange W. B. MOORE, Manager. j. :rnu J ; 104 to no Franlclin Street ‘ Washington . (Cor. CHICAGO INDEX TO LANTERNS, ETC. FOR INDEX TO SLIDES SEE INDEX AT CLOSE OF CATALOGUE. Page Acetylene Dissolver 28 Champion Lantern 3g to 42 “ Gas 60 Check Valve S3 •* 1 • .• Gas Burner.... ; 19 Chemicals, Oxygen 74, 81 ** < .' I j Gas Generator.. ; 61 to 66 Chirograph 136 “ Gas Generator, Perfection to 66 64 Chlorate of Potash, tee Oxygen Chemicals 74 Adapter from to sire lenses, see Chromatrope.... 164 Miscellaneous....... 174 Cloak, How Made 151 Advertising Slides, Blank, see Miscellaneous.. 174 ** Slides 38010,387 " Slides 144 Color Slides or Tinters .^140 “ Slides, Ink for Writing, see Colored Films 297 Miscellaneous, 174 Coloring Films 134 “ Posters * *...153 " Slides Alcohol Vapor Mantle Light 20A v 147 Combined Check or Safety Valve 83 Alternating.Carbons, Special... 139 Comic and Mysterious Films 155 Allen Universal Focusing Lens 124, 125 Comparison of Portable Gas Outfits 93, 94 America, Wonders cf Description, 148 “Condensing Lens 128 Amet's Oro-Carbi Light 86 to 92, 94 " Lens Mounting 128 •Ancient Costumes ....! 131 Connections, Electric Lamp and Rheostat... 96, 97 Approximate Length of Focus 123 " Electric Stage 139 Arc Lamp 13 to 16 Costumes 130 to 152, 380 to 3S7 ** Lamp and Rheostat, How to Connect 96 Cover Glasses, see Miscellaneous ,....174 Arnold's Improved Calcium Light Outfit. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

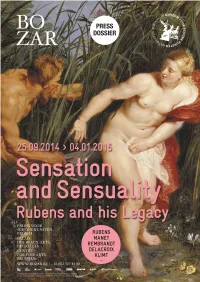

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Sir Anthony Van Dyck

CO N T E N T S k B H u h k e s Sir Anthony Van Dyc . y g St o ‘ List of su c h of the principal w ork s of Van Dyck as are in public Galleries L I ST O F I L L U ST R A T I O N S Portrait of T homas of Savoy Fron t zspzece T he R Coronation of St . osalie by the Child Jesus Minerva at the Forge of Vulcan T h e Virgin and Child with St . Joseph Saint Francis listening to Celestial M usi c Portrait of Prince Rupert of the Palatinate Portrait of Maria Louisa De T a s sis Christ on the Cross T h e Lamentation over Christ J esus bearing the Cross S h his n aint Sebastian , wit angels removing the arrows from wou ds T he Virgin and Child with two Donors Rinaldo and Armida P I ortrait of Charles . Portraits of Prince Charles Louis and Prince Rupert of B avaria Portrait of T h e Duk e of Richmond T h e Virgin and Child with the M agdalen Christ crowned with T horns P S his W Son ortraits of ebastian Leerse , ife and Saint Jerome T h e Drunk en Silenus H M l I enrietta aria , Queen to Char es . Portrait of the Painter P M R t W the ortrait of ary u hven , ife of Artist Portrait of an Artist T h e E mperor T heodosius refused admission 1rto the Church a n Portrait of Cornelius . -

Annual Report 2004

mma BOARD OF TRUSTEES Richard C. Hedreen (as of 30 September 2004) Eric H. Holder Jr. Victoria P. Sant Raymond J. Horowitz Chairman Robert J. Hurst Earl A. Powell III Alberto Ibarguen Robert F. Erburu Betsy K. Karel Julian Ganz, Jr. Lmda H. Kaufman David 0. Maxwell James V. Kimsey John C. Fontaine Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Leonard A. Lauder & Alexander M. Laughlin Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Victoria P. Sant Joyce Menschel Chairman President Chairman Harvey S. Shipley Miller John W. Snow Secretary of the Treasury John G. Pappajohn Robert F. Erburu Sally Engelhard Pingree Julian Ganz, Jr. Diana Prince David 0. Maxwell Mitchell P. Rales John C. Fontaine Catherine B. Reynolds KW,< Sharon Percy Rockefeller Robert M. Rosenthal B. Francis Saul II if Robert F. Erburu Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. David 0. Maxwell Chairman I Albert H. Small John W. Snow Secretary of the Treasury James S. Smith Julian Ganz, Jr. Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson David 0. Maxwell Roselyne C. Swig Victoria P. Sant Luther M. Stovall John C. Fontaine Joseph G. Tompkins Ladislaus von Hoffmann John C. Whitehead Ruth Carter Stevenson IJohn Wilmerding John C. Fontaine J William H. Rehnquist Alexander M. Laughlin Dian Woodner ,id Chief Justice of the Robert H. Smith ,w United States Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine President Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Director Heidi L. Berry Alan Shestack W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Deputy Director Elizabeth Cropper Melvin S. Cohen Dean, Center for Advanced Edwin L. Cox Colin L. Powell John W. -

'Crime of the Century'

HIGH NOON BECKONS IN THE ARTWORLD’S ‘CRIME OF THE CENTURY’ GIULIANO RUFFINI has been in the headlines since 2016, when French authorities began investigating his onetime ownership of works by Cranach, Hals, Parmigianino and Gentileschi, among others. That investigation was prompted by a Poison-Pen Letter accusing Ruffini of selling not bona fide Old Masters, but Fakes... and, almost unbelievably, fakes good enough to fool the world’s top dealers, auctioneers, museum curators and private collectors – and sell for millions. That anonymous missive is here made public for the first time – with Giuliano Ruffini pointing the finger at man he believes wrote it: his ex-associate JEAN-CHARLES METHIAZ . The two former lady-killers, now in their mid-seventies, have spent the coronavirus lockdown in isolation at opposite ends of Italy: Ruffini with his son Mathieu in the rugged Apennine Hills south of Parma; Méthiaz with his dogs Oscar and Gaston amidst the olive groves of Apulia. Ruffini has been passing the time on home restoration, Méthiaz by posting lengthy diatribes on Facebook. His favourite targets: French President Emmanuel Macron (‘a demented manipulator’); his predecessor François Hollande (‘an incapable moron’); and ‘Al Capone’ – which is how Jean-Charles Méthiaz refers to Giuliano Ruffini. ‘The Head of Old Masters at a prestigious auction house told me that, if they know a painting comes from Ruffini, they don’t even want to look at it’ wrote Méthiaz in March 2020. ‘He even added that this man was the devil.’ When Ruffini and Méthiaz finally emerge blinking into the sunlight, it will be at High Noon – for a shoot-out in France’s Civil Court on 20 May 2021 over what, in another post, Méthiaz has dubbed ‘ l’escroquerie du siècle. -

The Seven Last Words of Christ

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The seven last words of Christ : a comparison of three French romantic musical settings by Gounod, Franck, and Dubois Vaughn Roste Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Roste, Vaughn, "The es ven last words of Christ : a comparison of three French romantic musical settings by Gounod, Franck, and Dubois" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3987. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SEVEN LAST WORDS OF CHRIST: A COMPARISON OF THREE FRENCH ROMANTIC MUSICAL SETTINGS BY GOUNOD, FRANCK, AND DUBOIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Vaughn Roste B.A., Augustana University College, 1997 B.B.A, Canadian Lutheran Bible Institute, 1997 M.Mus., University of Alberta, 2003 May 2013 ii DEDICATION Writing a dissertation is a project not completed by one person but by several. I need to thank my family—Mom, Dad, Erica, Ben, Finn, and Anders—for their love and undying support through this convoluted and seemingly never-ending process. -

Loans in And

LOANS TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY April 2018 – March 2019 The following pictures were on loan to the National British (?) The Fourvière Hill at Lyon (currently Leighton Archway on the Palatine Gallery between April 2018 and March 2019 on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Leighton Houses in Venice *Pictures returned Bürkel Distant View of Rome with the Baths Leighton On the Coast, Isle of Wight of Caracalla in the Foreground (currently on loan Leighton An Outcrop in the Campagna THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST / to the Ashmolean Museum Oxford) Leighton View in Capri (currently on loan HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Buttura A Road in the Roman Campagna to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Fra Angelico Blessing Redeemer Camuccini Ariccia Leighton A View in Spain Gentile da Fabriano The Madonna and Camuccini A Fallen Tree Trunk Leighton The Villa Malta, Rome Child with Angels (The Quaratesi Madonna) Camuccini Landscape with Trees and Rocks Possibly by Leighton Houses in Capri Gossaert Adam and Eve (currently on loan to the Ashmolean Mason The Villa Borghese (currently on loan Leighton Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is carried Museum, Oxford) to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) in Procession through the Streets of Florence Cels Sky Study with Birds Michallon A Torrent in a Rocky Gorge (currently Pesellino Saints Mamas and James Closson Antique Ruins (the Baths of Caracalla?) on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Closson The Cascade at Tivoli (currently on loan Michallon A Tree THE WARDEN AND FELLOWS OF to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Nittis Winter Landscape ALL -

Robert Kingsley.Pdf

Robert Kingsley A Retrospective 1976-2012 Acknowledgments I want to take this opportunity to thank the individuals who have supported me over these many years: my parents, who encouraged me but never pushed me toward a particular vocation; my wife, Patricia, (who still inspires me) and our children, Matthew and Stephanie, who permitted me the long hours I spent in the studio to produce my paintings; and of course, the galleries and my patrons. This truly is, and has been, “La Dolce Vita,” a life I could have never imagined when I first began this sojourn so many years ago. It has been, and remains, a wonderful time, made better by the willingness of so many individuals who have supported my painting over the years. DePauw University and my colleagues also played a large role in this journey. I benefited immensely from their willingness to support my research, my sabbatical projects and my exhibitions. I have lived a life full of great experiences. Hopefully, I have offered the many young people I have taught some encouragement and insight into finding their bliss by following the advice Joseph Cornell gave his students: “Follow your bliss and the universe will open doors where there were only walls.” When I first began this journey, I believed that I might be the next darling of the art world, but as time passed, I began to realize that it was enough to enjoy an appreciation and honest devotion to the visual arts. It is a life that I can honestly say has been enriched by the people that I touch and that have touched me. -

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections AACHEN, STÀDTISCHES SUERMONDT ANTWERP, KONINKLIJK MUSEUM MUSEUM VOOR SCHONE KUNSTEN Anonymous, oil sketch after Rubens: Rubens, paintings: The Crucifixion (Coup de Lance), No. Christ Expiring on the Cross, No.30; fig.96; 123-126 7, copy; 149 The Crucifixion (Coup de Lance), No.37; fig.110; 139-146 The Lamentation (triptych), Nos.64-68 AALST, M.V.VAN GHYSEGHEM The Lamentation, No.64; ftg.192; 222-225 Anonymous, painting after Rubens: The Virgin and Child, No.65; fig.195; 225-226 Christ Carrying the Cross, No.18, copy 2; 77 St John the Evangelist, No.66;flg .l9 6 ; 226-227 Christ Holding the Globe, No.67; fig.198; 227-228 The Virgin and Child, No.68; fig.199; 228 AARSCHOT, CHURCH OF OUR LADY Rubens's studio, painting after Rubens: J.B.Ketgen, painting after Rubens: The Descent from the Cross, No.43, copy 1; 162 Christ ana the Virgin (from The Lamentation with Anonymous, painting after Rubens: St Francis), No.70, copy 1; 229 The Lamentation, No.62, copy 1 ;fig,190; 218 ALMELO, J.H. GROBBEN ANTWERP, KREFIRMA Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Anonymous, painting after Rubens: The Crucifixion (Coup de Lance), No.37, copy 28; Christ Expiring on the Cross, No.31, copy 11; 128 ' 141 ANTWERP, ROCKOXHUIS AMSTERDAM, J.J. GELUK Rubens, oil sketch: Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Christ on the Cross Addressing His Mother, St John The Lamentation, No.64, copy 14; 222 and St Mary Magaalen, No.34; fig.104; 133-136 AMSTERDAM, CHR. P. VAN EEGHEN ANTWERP, ST PAUL S CHURCH Rubens, drawing: Crouching Man Seen from the Back, No.20i; Rubens, painting: fig.73; 104-105 The Flagellation, N o.ll; fig.24; 59 Antoon van Ysendyck, painting after Rubens: AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM The Flagellation, No.