Dominicana 61.2 Winter 2018.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue and Price List of Stereopticons

—. ; I, £3,v; and Descriptive , Illustrated ;w j CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST- t&fs — r~* yv4 • .'../-.it *.•:.< : .. 4^. ; • ’• • • wjv* r,.^ N •’«* - . of . - VJ r .. « 7 **: „ S ; \ 1 ’ ; «•»'•: V. .c; ^ . \sK? *• .* Stereopticons . * ' «». .. • ” J- r . .. itzsg' Lantern Slides 1 -f ~ Accessories for Projection Stereopticon and Film Exchange W. B. MOORE, Manager. j. :rnu J ; 104 to no Franlclin Street ‘ Washington . (Cor. CHICAGO INDEX TO LANTERNS, ETC. FOR INDEX TO SLIDES SEE INDEX AT CLOSE OF CATALOGUE. Page Acetylene Dissolver 28 Champion Lantern 3g to 42 “ Gas 60 Check Valve S3 •* 1 • .• Gas Burner.... ; 19 Chemicals, Oxygen 74, 81 ** < .' I j Gas Generator.. ; 61 to 66 Chirograph 136 “ Gas Generator, Perfection to 66 64 Chlorate of Potash, tee Oxygen Chemicals 74 Adapter from to sire lenses, see Chromatrope.... 164 Miscellaneous....... 174 Cloak, How Made 151 Advertising Slides, Blank, see Miscellaneous.. 174 ** Slides 38010,387 " Slides 144 Color Slides or Tinters .^140 “ Slides, Ink for Writing, see Colored Films 297 Miscellaneous, 174 Coloring Films 134 “ Posters * *...153 " Slides Alcohol Vapor Mantle Light 20A v 147 Combined Check or Safety Valve 83 Alternating.Carbons, Special... 139 Comic and Mysterious Films 155 Allen Universal Focusing Lens 124, 125 Comparison of Portable Gas Outfits 93, 94 America, Wonders cf Description, 148 “Condensing Lens 128 Amet's Oro-Carbi Light 86 to 92, 94 " Lens Mounting 128 •Ancient Costumes ....! 131 Connections, Electric Lamp and Rheostat... 96, 97 Approximate Length of Focus 123 " Electric Stage 139 Arc Lamp 13 to 16 Costumes 130 to 152, 380 to 3S7 ** Lamp and Rheostat, How to Connect 96 Cover Glasses, see Miscellaneous ,....174 Arnold's Improved Calcium Light Outfit. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

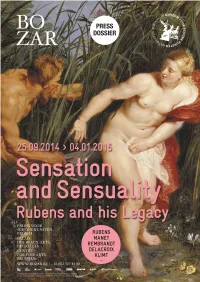

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Sir Anthony Van Dyck

CO N T E N T S k B H u h k e s Sir Anthony Van Dyc . y g St o ‘ List of su c h of the principal w ork s of Van Dyck as are in public Galleries L I ST O F I L L U ST R A T I O N S Portrait of T homas of Savoy Fron t zspzece T he R Coronation of St . osalie by the Child Jesus Minerva at the Forge of Vulcan T h e Virgin and Child with St . Joseph Saint Francis listening to Celestial M usi c Portrait of Prince Rupert of the Palatinate Portrait of Maria Louisa De T a s sis Christ on the Cross T h e Lamentation over Christ J esus bearing the Cross S h his n aint Sebastian , wit angels removing the arrows from wou ds T he Virgin and Child with two Donors Rinaldo and Armida P I ortrait of Charles . Portraits of Prince Charles Louis and Prince Rupert of B avaria Portrait of T h e Duk e of Richmond T h e Virgin and Child with the M agdalen Christ crowned with T horns P S his W Son ortraits of ebastian Leerse , ife and Saint Jerome T h e Drunk en Silenus H M l I enrietta aria , Queen to Char es . Portrait of the Painter P M R t W the ortrait of ary u hven , ife of Artist Portrait of an Artist T h e E mperor T heodosius refused admission 1rto the Church a n Portrait of Cornelius . -

The Seven Last Words of Christ

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The seven last words of Christ : a comparison of three French romantic musical settings by Gounod, Franck, and Dubois Vaughn Roste Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Roste, Vaughn, "The es ven last words of Christ : a comparison of three French romantic musical settings by Gounod, Franck, and Dubois" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3987. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SEVEN LAST WORDS OF CHRIST: A COMPARISON OF THREE FRENCH ROMANTIC MUSICAL SETTINGS BY GOUNOD, FRANCK, AND DUBOIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Vaughn Roste B.A., Augustana University College, 1997 B.B.A, Canadian Lutheran Bible Institute, 1997 M.Mus., University of Alberta, 2003 May 2013 ii DEDICATION Writing a dissertation is a project not completed by one person but by several. I need to thank my family—Mom, Dad, Erica, Ben, Finn, and Anders—for their love and undying support through this convoluted and seemingly never-ending process. -

Loans in And

LOANS TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY April 2018 – March 2019 The following pictures were on loan to the National British (?) The Fourvière Hill at Lyon (currently Leighton Archway on the Palatine Gallery between April 2018 and March 2019 on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Leighton Houses in Venice *Pictures returned Bürkel Distant View of Rome with the Baths Leighton On the Coast, Isle of Wight of Caracalla in the Foreground (currently on loan Leighton An Outcrop in the Campagna THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST / to the Ashmolean Museum Oxford) Leighton View in Capri (currently on loan HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Buttura A Road in the Roman Campagna to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Fra Angelico Blessing Redeemer Camuccini Ariccia Leighton A View in Spain Gentile da Fabriano The Madonna and Camuccini A Fallen Tree Trunk Leighton The Villa Malta, Rome Child with Angels (The Quaratesi Madonna) Camuccini Landscape with Trees and Rocks Possibly by Leighton Houses in Capri Gossaert Adam and Eve (currently on loan to the Ashmolean Mason The Villa Borghese (currently on loan Leighton Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is carried Museum, Oxford) to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) in Procession through the Streets of Florence Cels Sky Study with Birds Michallon A Torrent in a Rocky Gorge (currently Pesellino Saints Mamas and James Closson Antique Ruins (the Baths of Caracalla?) on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Closson The Cascade at Tivoli (currently on loan Michallon A Tree THE WARDEN AND FELLOWS OF to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Nittis Winter Landscape ALL -

The Jesus Project: an Artistic Definition of the Sacred

THE JESUS PROJECT: AN ARTISTIC DEFINITION OF THE SACRED FEMININE A Thesis by MIRIANA ILIEVA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2003 Major Subject: Visualization Sciences THE JESUS PROJECT: AN ARTISTIC DEFINITION OF THE SACRED FEMININE A Thesis by MIRIANA ILIEVA Submitted to Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved as to style and content by: 0 0 Carol LaFayette Karen Hillier (Chair of Committee) (Member) 0 0 Andruid Kerne Phillip Tabb s ss(Member) (Head of Department) December 2003 Major Subject: Visualization Sciences iii ABSTRACT The Jesus Project: an Artistic Definition of the Sacred Feminine. (December 2003) Miriana Ilieva, B.A., Smith College Chair of Advisory Committee: Prof. Carol LaFayette This thesis presents The Jesus: a project about the representation of the Crucifixion in Renaissance art. After determining the cultural codes for depicting women, it is established that Renaissance representations of the Crucifixion portray Christ in an extraordinarily feminine and sensual light. The development of the project is documented in terms of the creative process and the conceptual and darkroom experiments involved in the creation of the artwork. Finally, contemporary artworks similar to The Jesus are discussed in the context of religious imagery. iv DEDICATION In memory of my grandfather Valtcho Michailov. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee chair Carol LaFayette for her dedicated guidance, strong commitment, encouragement and care. Thank you to Karen Hillier and Andruid Kerne for their wonderful support and great input. -

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections AACHEN, STÀDTISCHES SUERMONDT ANTWERP, KONINKLIJK MUSEUM MUSEUM VOOR SCHONE KUNSTEN Anonymous, oil sketch after Rubens: Rubens, paintings: The Crucifixion (Coup de Lance), No. Christ Expiring on the Cross, No.30; fig.96; 123-126 7, copy; 149 The Crucifixion (Coup de Lance), No.37; fig.110; 139-146 The Lamentation (triptych), Nos.64-68 AALST, M.V.VAN GHYSEGHEM The Lamentation, No.64; ftg.192; 222-225 Anonymous, painting after Rubens: The Virgin and Child, No.65; fig.195; 225-226 Christ Carrying the Cross, No.18, copy 2; 77 St John the Evangelist, No.66;flg .l9 6 ; 226-227 Christ Holding the Globe, No.67; fig.198; 227-228 The Virgin and Child, No.68; fig.199; 228 AARSCHOT, CHURCH OF OUR LADY Rubens's studio, painting after Rubens: J.B.Ketgen, painting after Rubens: The Descent from the Cross, No.43, copy 1; 162 Christ ana the Virgin (from The Lamentation with Anonymous, painting after Rubens: St Francis), No.70, copy 1; 229 The Lamentation, No.62, copy 1 ;fig,190; 218 ALMELO, J.H. GROBBEN ANTWERP, KREFIRMA Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Anonymous, painting after Rubens: The Crucifixion (Coup de Lance), No.37, copy 28; Christ Expiring on the Cross, No.31, copy 11; 128 ' 141 ANTWERP, ROCKOXHUIS AMSTERDAM, J.J. GELUK Rubens, oil sketch: Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Christ on the Cross Addressing His Mother, St John The Lamentation, No.64, copy 14; 222 and St Mary Magaalen, No.34; fig.104; 133-136 AMSTERDAM, CHR. P. VAN EEGHEN ANTWERP, ST PAUL S CHURCH Rubens, drawing: Crouching Man Seen from the Back, No.20i; Rubens, painting: fig.73; 104-105 The Flagellation, N o.ll; fig.24; 59 Antoon van Ysendyck, painting after Rubens: AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM The Flagellation, No. -

Sir Anthony Van Dyck

CO N T E N T S k B H u h k e s Sir Anthony Van Dyc . y g St o ‘ List of su c h of the principal w ork s of Van Dyck as are in public Galleries L I ST O F I L L U ST R A T I O N S Portrait of T homas of Savoy Fron t zspzece T he R Coronation of St . osalie by the Child Jesus Minerva at the Forge of Vulcan T h e Virgin and Child with St . Joseph Saint Francis listening to Celestial M usi c Portrait of Prince Rupert of the Palatinate Portrait of Maria Louisa De T a s sis Christ on the Cross T h e Lamentation over Christ J esus bearing the Cross S h his n aint Sebastian , wit angels removing the arrows from wou ds T he Virgin and Child with two Donors Rinaldo and Armida P I ortrait of Charles . Portraits of Prince Charles Louis and Prince Rupert of B avaria Portrait of T h e Duk e of Richmond T h e Virgin and Child with the M agdalen Christ crowned with T horns P S his W Son ortraits of ebastian Leerse , ife and Saint Jerome T h e Drunk en Silenus H M l I enrietta aria , Queen to Char es . Portrait of the Painter P M R t W the ortrait of ary u hven , ife of Artist Portrait of an Artist T h e E mperor T heodosius refused admission 1rto the Church a n Portrait of Cornelius . -

Illustrated Biographies Of

—Ed ' l w s m z Revie . A eservi S r e base u on r ce t G rma l cat ons. znb d ng e i , d p e n e n pub i i g — e a or Most thoroughly and tastefully edited Sp ct t . ILLU STRATED BIOG RAPHIES OF THE G REAT ARTISTS. Each volumis l strat t fro 1 2 to 20 f a E rav n s r nte in the e i lu ed wi h m ull e ng i g , p i d est a er and o orna e ta c oth cov r s . 6d b m nn , b und in m n e , 3 . Froma R eview in TH E S P CTATO l E R u 1 8 . , y y 5, 79 It is high time that some thorough and general acquaintance with the works of these t ai t rs s o s r a a roa and it is a so c r o s to t k how o t r a s migh y p n e h uld be p e d b d , l u i u hin l ng hei n me ’ hav occ i sacr ic s in the or s art Wit o t the rese c of c o ar k o e up ed ed n he w ld he , h u p n e mu h p ul n w he co t v k of t r s If he f Io a hies a o t t c i or i iv . -

Panels Between Rubens and Van Dyck

Panels Between Rubens and Van Dyck Gaspar de CRAYER From an artistic background, Gaspar de Crayer was born in Antwerp, in 1584. His father was a schoolmaster, as well as an illuminator and calligrapher. According to historical sources, De Crayer carried out his apprenticeship in Brussels under Raphael Coxie (around 1540-1616), who specialized in history painting and portraits in the Mannerist style. It is unknown at what age he moved from Antwerp to Brussels, home to both the Court and government, which gave him the opportunity to establish his reputation. The artist distinguished himself in two genres – portraiture and religious painting – which were sometimes combined in a single composition. Prolific in his production, his career spanned an impressively long period since he continued painting vast altarpieces into his eighties. His image was immortalized by one of the greatest masters of the 17 th century, Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). The only known self-portrait is in The Adoration of the Magi , in which De Crayer depicted himself as a gentleman . aaa 1.1 bbb Jacob JORDAENS (Antwerp, 1593-1678), attributed to — Portrait of Gaspar de Crayer Around 1640 Oil on canvas Private collecon Aged around fiy and at the height of his career, De Crayer as immortalised by Anthony van Dyck ho painted this first portrait of the arst, no held in the Prince of Liechtenstein’s collecons ((ienna). The ork presented here is thought to be a copy by ,acob ,ordaens hich remains faithful to (an Dyck’s composion. The poise and bearing of the sub-ect command the observer’s a.enon.